An Unofficial Brief on Toxic Nationalist Metaphors and Ice Cream Cones in the Sun

History is a concept that I have trouble with, not only because it tends to be written by conquerors, thereby offering explanations and accounts of events that justify socio-cultural and economic domination; and not only because it tends to signify a cohesive and coherent past, as if naturally occurring and not constructed. I am also troubled by history because of my need for it. Despite the overwhelming influence that Mexican-origin culture and labor has had in shaping this nation, the Chicana/o experience and perspective rarely appear within its official narrative. And when it does, suspicion is the correct response, because nationalist bias and ethnic prejudice are without a doubt close at hand. So, this piece is partly a history, but it is also about a particular photograph taken by Roger Minick while participating in a two-year long, socio-documentary project that endeavored to materialize Chicana/o life within the nation’s aesthetic, cultural milieu.*

Between 1977 and 1979, after the initial thrust of the Chicana/o civil rights movement and before the all-out assault of the culture wars, five photographers travelled throughout the US Southwest focusing their lenses on Mexican-American life. Abigail Heyman, Neal Slavin, Louis Carlos Bernal, Morrie Camhi, and Roger Minick were supported in their efforts by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), as well as by the National Endowment for the Arts. Envisioned as a commemoration of MALDEF’s tenth year anniversary, the project resulted in an exhibition—Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American—which toured Oakland, Los Angeles, and Chicago. As the project’s principle architect, Morrie Camhi shaped its ideological approach in opposition to other socio-documentary initiatives, which tended to reduce the photographer’s role to propagandist, or the illustrator of some preconceived message. This stance, in favor of artistic autonomy while also attempting to create knowledge about the Mexican-American experience in the US, helps explain the ambiguous results produced by the project, with some photographers balancing the two directives better than others.

In many ways, Espejo reflects the anxious relationship between Anglo Americans and Mexican Americans in structuring the possibilities by which Chicana/o life and culture are presented and represented within the larger public sphere. It is worth noting, for example, that despite the project’s ethnic and cultural focus Louis Carlos Bernal was the only Mexican-American participant. Although Camhi merits credit for soliciting the input of Mexican American community members in the early stages of Espejo’s development. MALDEF also leveraged its own interests by reaching out and finding people to act as liaisons between the forthcoming photographers and the people they would be photographing. This advance work constitutes an attempt to mitigate the language and cultural barriers the project would inevitably create. Moreover, it expresses a desire that the depicted communities be engaged with in a meaningful way, as opposed to observed from afar by a disinterested outsider.

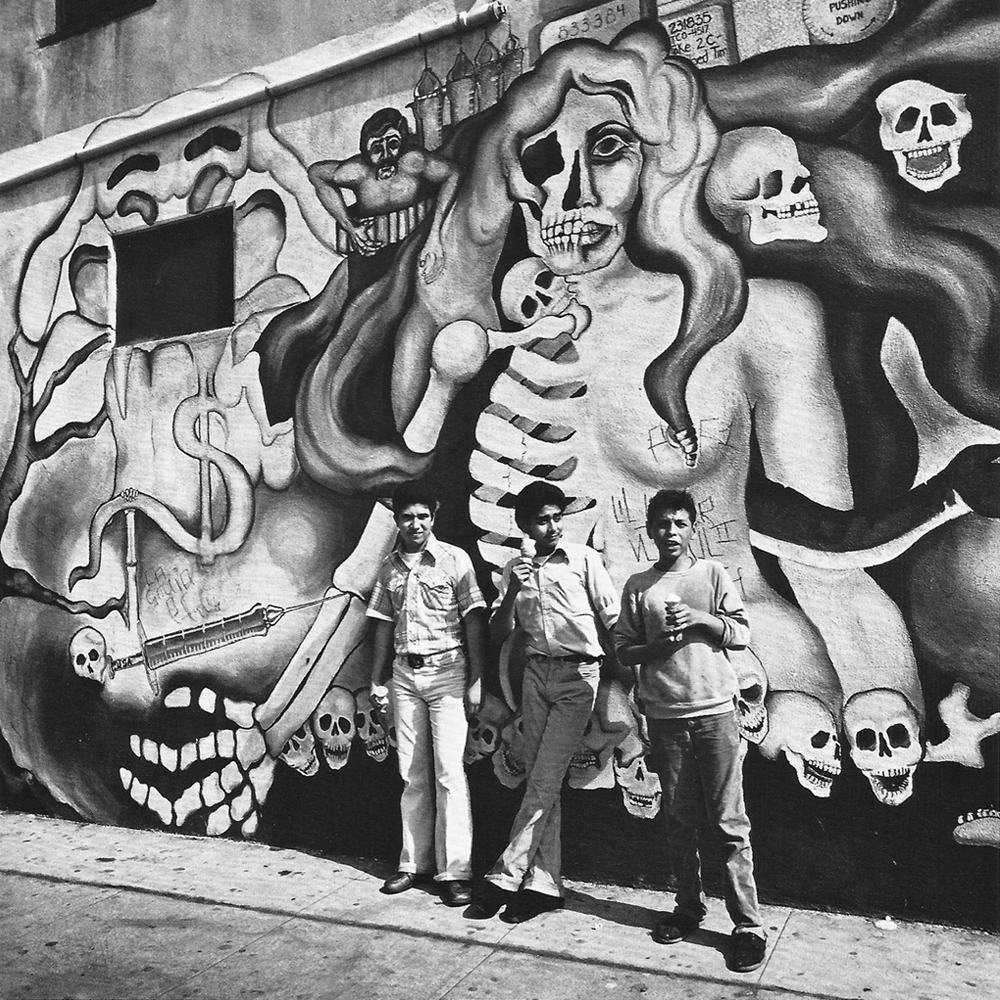

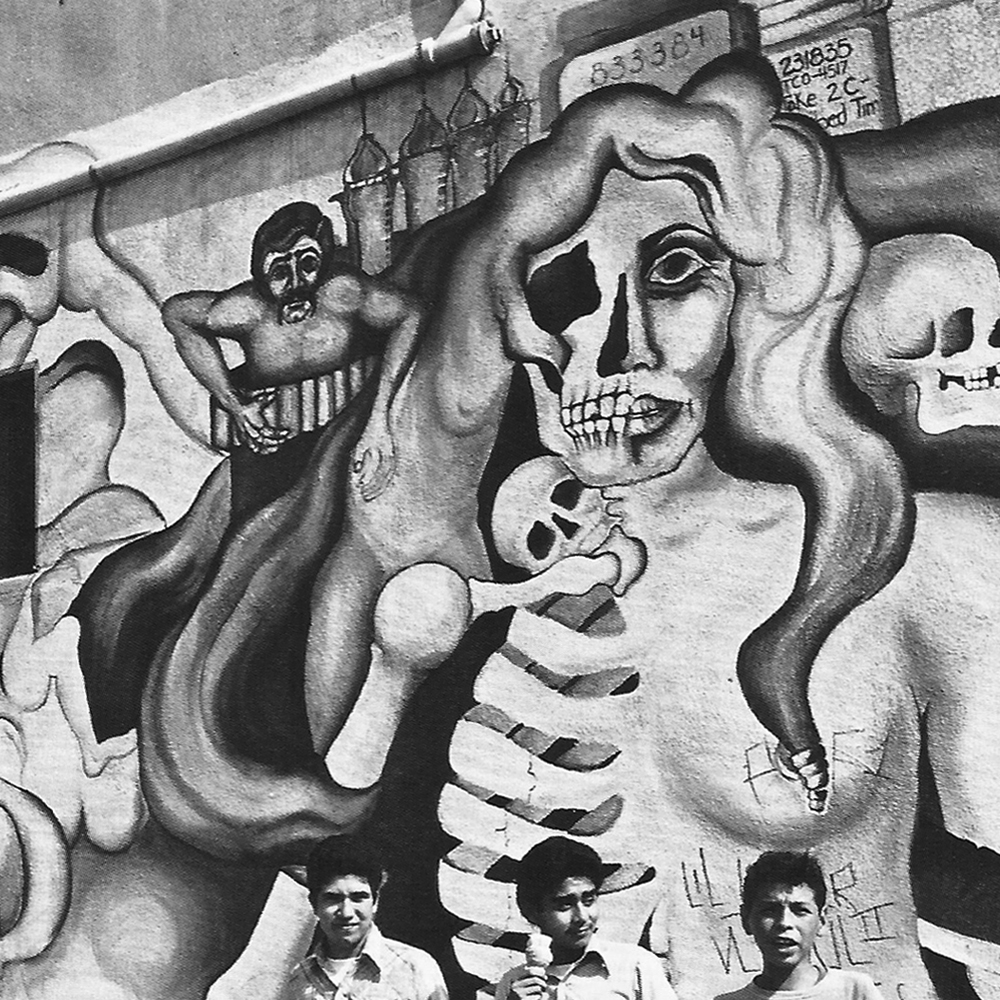

Roger Minick’s response to the iconic street murals of East L.A. clearly relates to the historically uneasy relationship between Anglo image makers and their “othered” objects of study. By placing various Chicana/o bodies in front of local murals and photographing the resulting scenes, Minick risks reducing the neighborhood residents to visual pawns. This is particularly true given that his subjects often go unnamed. The void of historical anonymity is especially empty for those whom dominant social groups have marginalized; any appearance of the unidentified brown body naturally provokes both misgivings and longings. Nevertheless, Minick’s desire to arrange brown bodies is balanced against his understanding of the street mural as more than an exotic site of graphic consumption. “The murals reflect the social conflicts faced by the immigrant Mexican,” Minick writes, “as well as the second and third generation Mexican American in his or her adjustment to American society.” Ultimately, Minick’s photographs heighten and make overt the already occurring interaction between Chicana/os and their urban-visual environments—an interaction that Chicana/os were responsible for initiating.

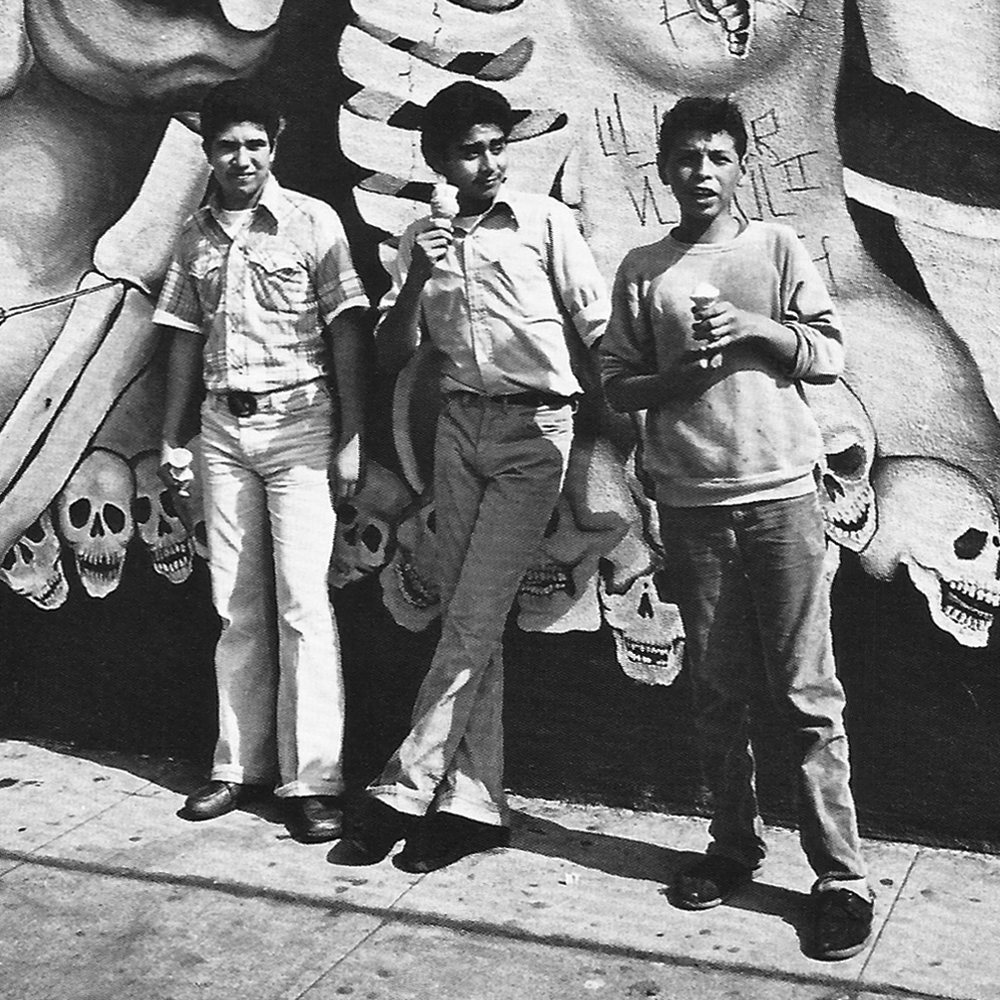

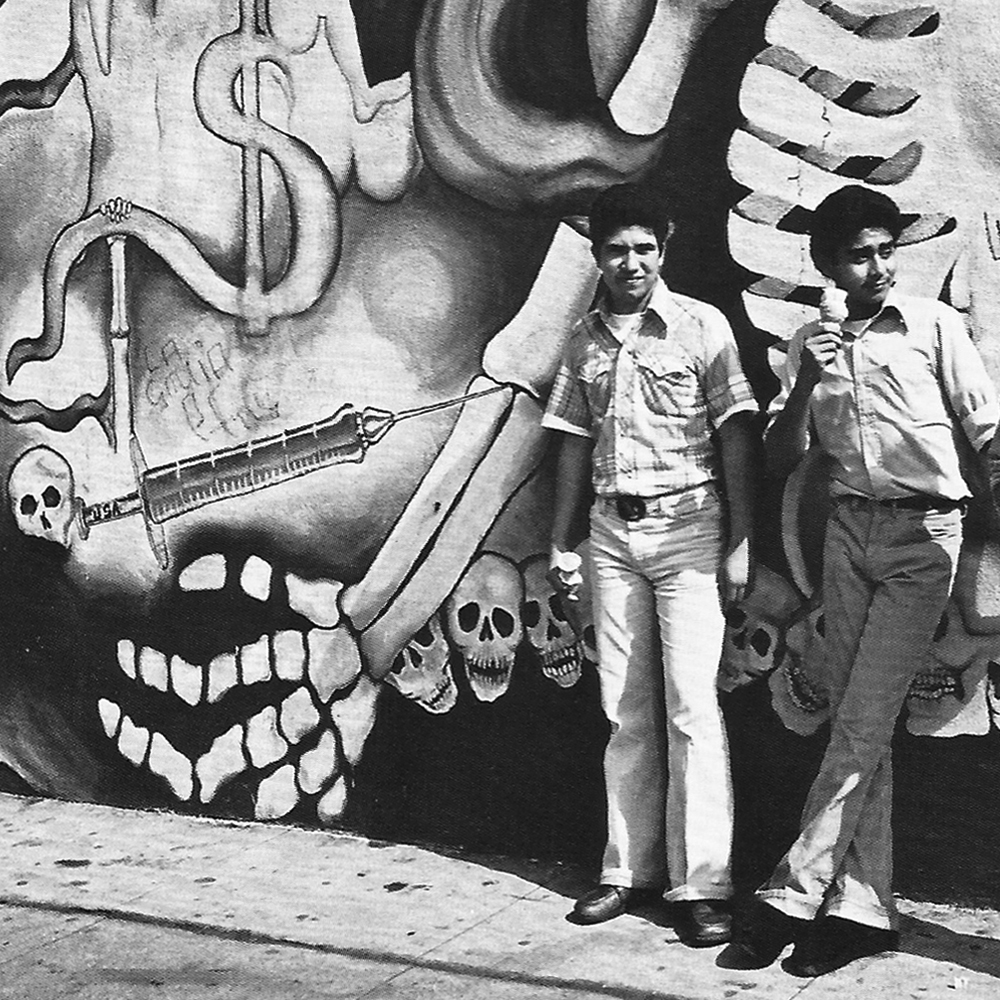

The interplay between the teenagers and the wall painting in Minick’s photograph, Three boys with ice cream, 1977, presents a complicated image of Mexican-American, urban existence. Despite being prearranged, the boys take control of their bodies. The two adolescents on the left lean casually against the painting. One looks silently into the lens, alert to the fact that a picture is being made. The other, legs crossed, gazes at something beyond the frame. There, just past the edge, he seems to suggest, is more and more of the “real.” The photograph’s ability to apprehend the vastness of reality is cast in doubt. The youth to the right is by far the most active. In mid-utterance, fully detached from the wall, he moves toward the camera, toward the viewer, and comes closest to the picture’s edge. As self-posed agents, the boys are not simply expressions of an Anglo photographer’s vision. And while Minick’s portrayals are dramatic, socio-photographic constructions, there is also room for the spontaneous and unremarkable, for his subject’s gestures. The commonplace act of wadding a napkin underneath a melting ice cream cone takes on uncertain meaning when performed here, against this wall.

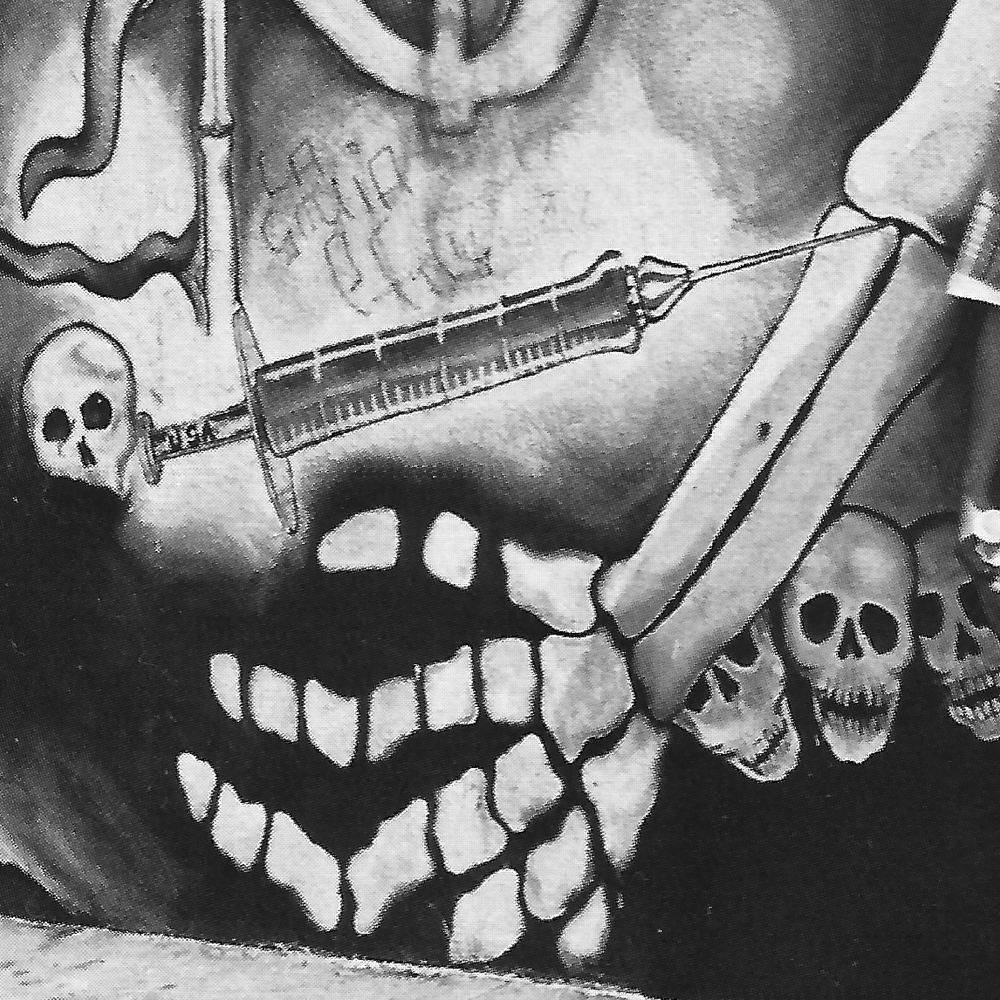

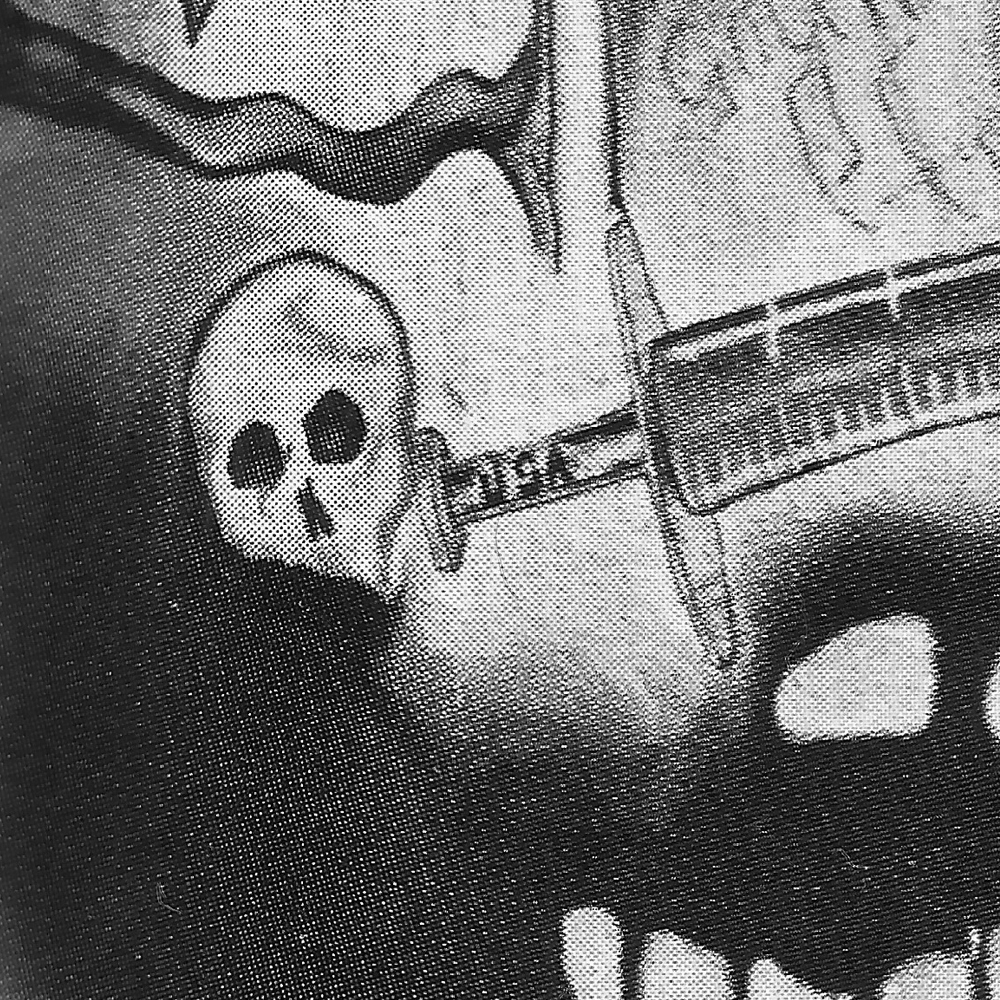

The mural is undeniably provocative. A nude, female figure in a bifurcated state of decomposition fills the wall from top to bottom, while screaming skulls materialize from a swirling, spectral ectoplasm. A man, part addict part pusher, emerges from an abstract structure near a row of upright hypodermic needles referencing a cityscape. Finally, and with finality, a needle pierces the central figure’s boney forearm injecting an unknown substance into the marrow—a powerful symbol of life gone septic. It is without a doubt problematic that the allure of drugs and the destruction they cause are sexualized and expressed through the exposed and distressed female form. Equally problematic is the foregone connection between these three boys and drug use. Somehow they seem more doomed by their complexions as they (the complexions) operate in proximity to this mural. On its surface, the photograph reads as foreshadowing for an inevitable future ruined by addiction.

However, the mural is not strictly an anti-drug image; thus, Minick’s photograph is not simply an allegory of brown youth and drug abuse. In fact, much of the mural’s meaning hinges on a tiny, almost unnoticeable, detail. Painted on the needle’s plunger is the abbreviation “USA.” And although this element may be hard to see in a reproduction, in person it must have been easily noticed. As a result, the mural opens onto a complex interchange between being Chicana/o and living in the United States, between the bronze body and the toxicity of a nationalism defined in opposition to the split subject, the US citizen held at a distance, the hyphenated Mexican-American. Clearly these boys are arranged in a way that suggests they are at risk to delinquency. But they are equally at risk to the biopolitics of a nation built on a fantasy of white purity. Ultimately, they are at risk to the pitfalls of adjusting to a society that routinely ostracizes and dehumanizes its Mexican-origin citizens.

Minick’s use of high-contrast, black and white photography collapses the visual space between the boys and the mural. They seem trapped within the lethal backdrop and its associations of racist, nationalist discourse. In particular, the boy closest to the painted needle appears to receive the same venomous injection as the ghastly figure looming overhead. And while he is carefree at the moment, bleak thoughts are triggered—but not simply of drug use. Something more multilayered and ominous is at play; something related to the “USA” and its affect on the Chicana/o psyche and body. Still, the photograph is not strictly pessimistic; it also holds out hope. Whatever forces are at work painting these boys into deadly corners, the gesture as self-possession is also at work, along with the power of community and friendship; and, of course, eating ice cream cones in the sun.

Notes:

*The history rehearsed regarding Espejo can be found in greater detail in Joan Murray’s catalog essay, “A Celebration,” Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American. Oakland, Calif: The Museum, 1978. Print.

*Three boys with ice cream, 1977, by Roger Minick appears on page 31 in Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American. Oakland, Calif: The Museum, 1978. Print.

*Quotes by Roger Minick found on page 24 in Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American. Oakland, Calif: The Museum, 1978.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.