The Grotesque: Mischief and Wonder in Renaissance Art

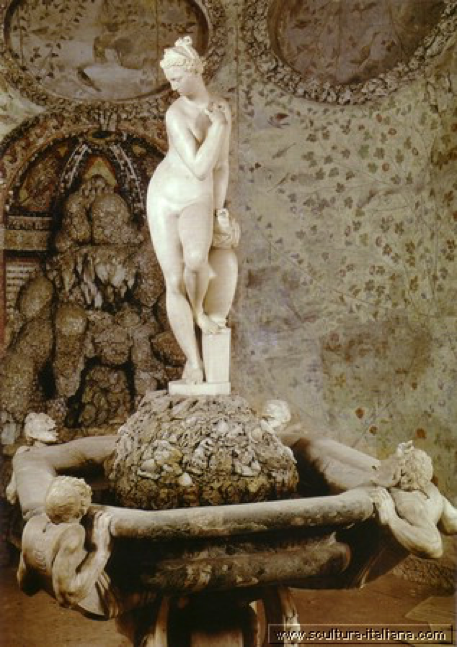

In the Boboli gardens, built in Florence in the 1550s for the wife of Cosimo I de Medici, is an artificial grotto. At the center stands a fountain which, on close inspection, may be found by the visitors to be puzzling at best. On a little mound of artificial rock, a seemingly classical Venus, proportionate and elegant, stands in a graceful pose. But below her, peeking from the basin, four humanoid figures lurk, leering at her body. In the past, the figures would have spouted water at her as if salivating. Through this striking contrast, the classical nudity of Venus becomes an exposed nakedness, and the viewers have the impression of standing before an altogether unpleasant scene reminiscent of the iconography of Susannah and the Elders.

“Venere che esce dal bagno” Buontalenti Grotto, Boboli Gardens

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susannah and the Elders (1622)

This contrast between the classical beauty of Venus and the mischievous ugliness of the creatures epitomizes the relationship between balanced form (valued by the great artists of the Renaissance) and the Grotesque, an artistic phenomenon which spread widely in the 16th century, especially in European garden architecture. Unlike Renaissance art, which we generally think of as being devoted to the Beautiful and to balanced yet naturalistic proportions, grotesque artworks shift the focus to the misshapen, the disproportionate, the fantastic and the delirious.

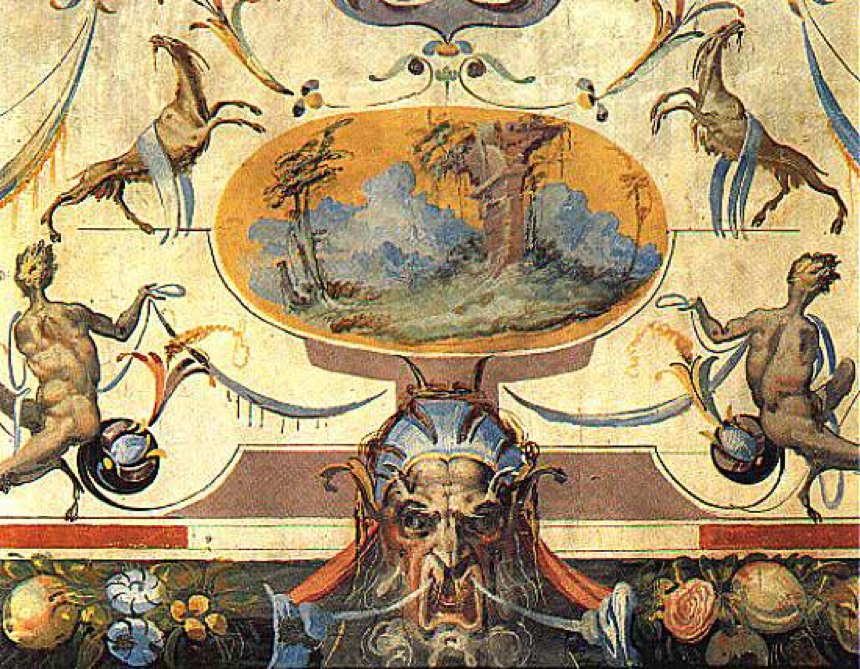

The origin of the word “grotesque” derives from the discovery, in the 16th century, of the ruins of the Domus Aurea, Emperor Nero’s unfinished and extravagant residence. The ruins, nicknamed “caves” (grotte in Italian), were decorated with frescos representing bizarre motifs inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Re-baptized as grottesche, these decorative patterns became a real fashion. Their subjects are mischievous, humorous, and fantastic: women transforming into columns, half-human and half-animal creatures, harpies, climbing plants sustaining impossible weights, and, most importantly, wide-mouthed masks (mascheroni).

Cesare Baglione, 1588, Rocca Meli Lupi Di Soragna (Parma, Italy)

Marco da Faenza, Decorazione grottesca, fresco detail, 16th century. Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

Giulio Parigi, grotesque fresco, 1599, Uffizi Gallery, Room 17

If our reaction, watching the details of these images, is wondering why the wealthiest families of the 16th century would have chosen to adorn their corridors and rooms in this manner, we are not alone. Already back in the day of the “original” grotesques, these designs had not failed to raise criticism. In his treatise De Architectura (25 BC), Vitruvius had this to say about the “depraved taste” of the artists of his time:

[…] monsters are now painted in frescoes rather than reliable images of definite things. Reeds are set up in place of columns, […] several tender shoots, sprouting in coils from roots, have little statues nestled in them for no reason, or shoots split in half, some holding little statues with human heads, some with the heads of beasts. Now these things do not exist nor can they exist nor have they ever existed […] How, pray tell, can a reed really sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the decorations of a pediment, or an acanthus shoot, so soft and slender, loft a tiny statue perched upon it, or can flowers be produced from roots and shoots on the one hand and figurines on the other? […] Minds beclouded by feeble standards of judgment are unable to recognize what exists in accordance with authority and the principles of correctness.[1]

Despite Vitruvius’s uncharitable judgement, in the 16th century grotesque images reflected a sensibility of the time, and even a reaction, it could be said, to the fixity and composure of Renaissance models. To stillness and severity, the grotesque contraposes a focus on metamorphosis, extravagance, and playfulness. The frequent representation of the mouth in these artworks is particularly telling—to the point of having been described by Mikhail Bakhtin as the feature of the grotesque.[2] The mouth has immediate associations with voracity, hunger, and physical drive (we need only to think about the salivating mouths of the creatures surrounding naked Venus), which were certainly not central subjects among the artists of the previous century.

In the late Renaissance, the phenomenon of the grotesque went far beyond mural painting, and these themes were frequent in other artistic media. In the Park of the Monsters of Bomarzo (in Lazio, Italy), a highly allegorical garden commissioned in the 16th century by Prince Pier Francesco Orsini, these elements find a most literal manifestation. One of the attractions of the park is the Ogre, a giant mask-like structure whose door is in fact a gaping mouth.

Ogre mask in the Gardens of Bomarzo

In the past, an inscription on the entrance misquoted Dante’s Inferno inviting the visitors to “relinquish all thought” while entering (this original inscription is no longer there) . To abandon their rationality, that is to say, to access a destabilizing, oneiric world. Strengthening even more the link between the grotesque image, the mouth, and voraciousness is the fact that inside the cavity is a stone table which could have been used for eating,

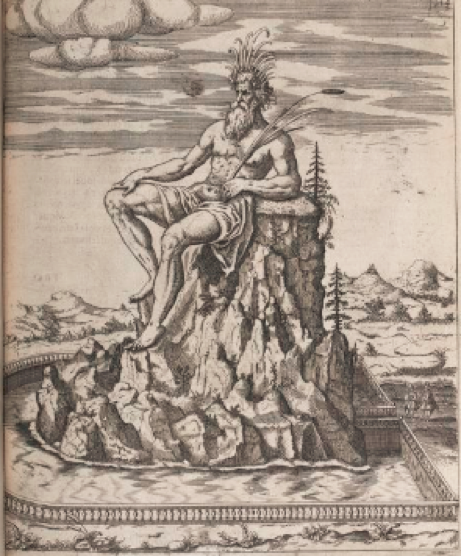

The garden of Bomarzo, with its colossal statues, is not the only one where visitors could walk into gigantic figures to be introduced to a world of wonder. The most iconic of such colossi is in fact the giant Appennino, an allegory of the local mountainous chain, in the Garden of Pratolino (now Villa Demidoff, Florence, Italy). The statue was built by Giambologna, the sculptor of the Venus analyzed above, and the park was designed by one of the most famous stage designers of the time: Buontalenti (again, the planner of the Boboli gardens and of the artificial grotto in which the Venus is located).

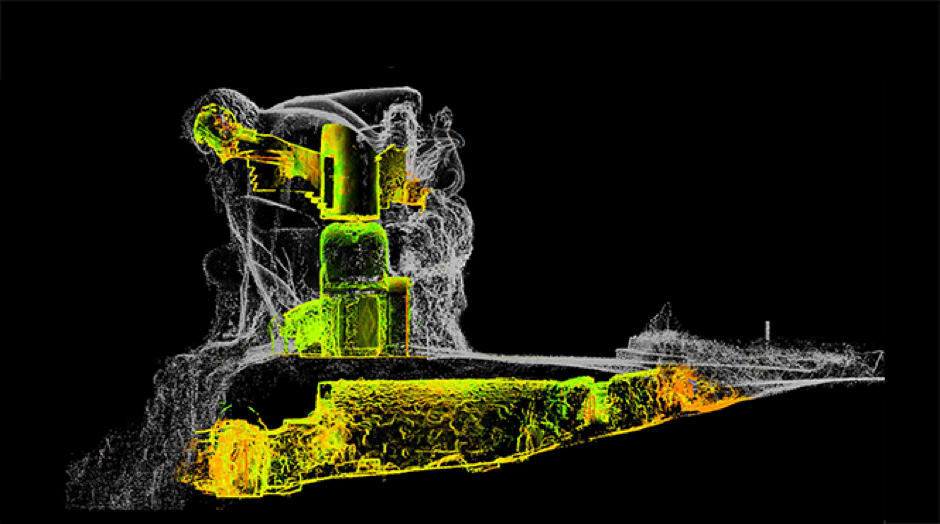

As the result of a renovation in Romantic times, the giant now appears more of a melancholy figure gazing thoughtfully at the pond below him. In the past, the statue would have elicited different associations. The colossus could have been accessed from the back, revealing a series of hidden chambers full of wonders. Although these internal rooms are now closed to the public, they still exist, as shown by 3D models made in 2011 by GeCo during the course of a renovation of the outer surfaces.

The relationship between internal spaces within the Giant (represented in false colours) shown in a transparent visualization of the external surface (in grey). Image via GeCo.

3D model of the cavities in the head and shoulders of the Appennino. Image via GeCo.

The internal chambers were decorated with artificial grottos encrusted with stones. Artificial grottos were another craze of the time, to the point that most palaces even had more than one. Because of the dense and eclectic assemblage of shells, fragments of various minerals, and stones imitating natural rock formations, grottos strike our contemporaries as being in rather poor taste, excessive, kitsch. As claimed by scholar Lauro Magnani, the lack of interest for such artifacts may be attributed to the fact that their original significance is lost to a contemporary audience. Yet in the 16th century, grottos reflected a widespread concern with the artificial imitation of the natural, and the relationship between the two, which was already being developed in imaginative ways in the fashion of Cabinets of Curiosities. This relationship was not only aesthetic but also animated by a vivid scientific interest for the natural world. This concern with imitation, with the manifestly fake, was also largely indebted to the popularity of theater plays at the time: classical statues, busts, niches, plaques, grotesque frescos, automata, and large masks were all part of the “ornamental vocabulary” of theater. Such motifs began to be included in paintings and to become popular features of garden architecture. At the same time, grottos had the same mysterious character which was sought after in gardens, as natural caves and pools were considered in Greek mythology to be the dwelling places of nymphs and other forest creatures.

It is interesting that, in such gardens, there is a recurring combination of grottos and automata, as they both reflected the said concern with the artificial recreation of nature and the mysterious or unusual. The grottos within the Giant of Pratolino did in fact contain automata, and French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote of having seen them in a grotto in the park.

[I saw] not only music and harmony made by the movement of the water, but also a movement of several statues and doors with various actions, caused by the water; several animals that plunge in to drink; and things like that. At one single movement the whole grotto is full of water, and all the seats squirt water on your buttocks; and if you flee from the grotto and climb the castle stairs and anyone takes pleasure in this sport, there come out of every other step of the stairs, right up to the top of the house, a thousand jets of water that give you a bath.[5]

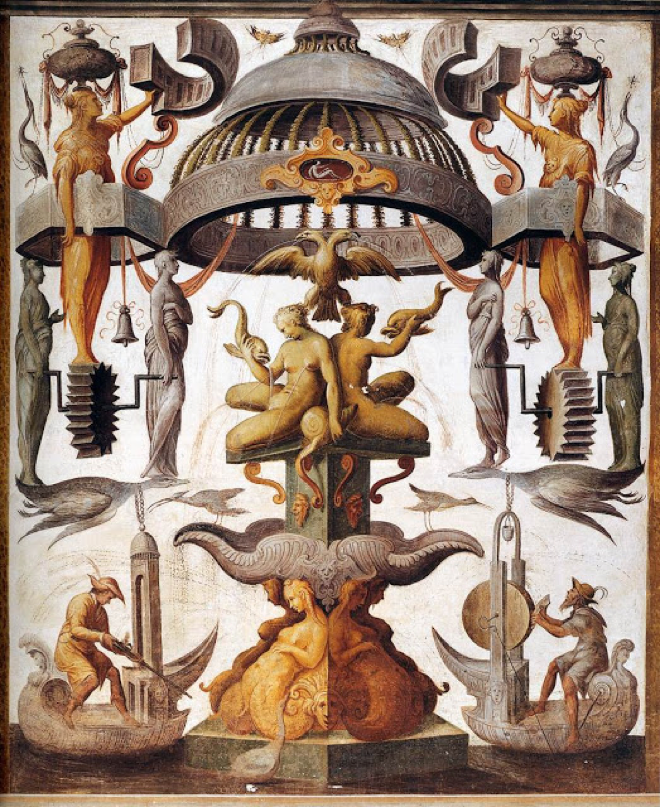

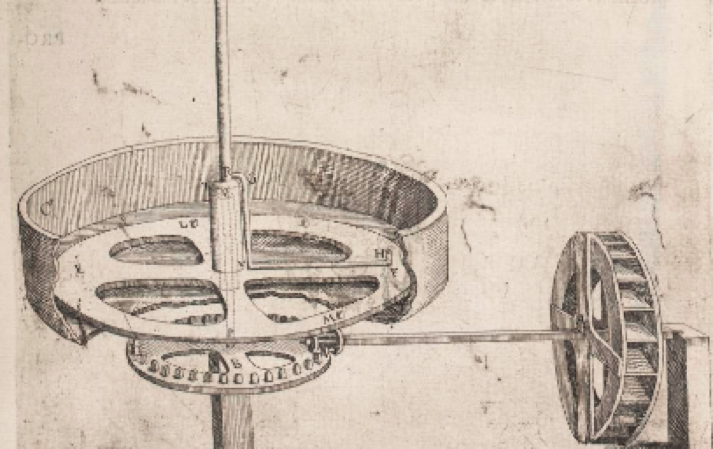

Engineer Salomon de Caus, an engineer who lived in the late 16th and early 17th century, built many hydraulic systems. He wrote a beautiful treatise on hydraulics, Les Raisons des Forces Mouvantes (1628), which is replete with illustrations of mechanical devices placed in grottos for the amusement of the visitors. He shows, for example, the mechanism used to make several mythological figures revolve around a pivot, or designs a giant similar to the one of Pratolino, inside which there should be a grotto with automated mythological figures playing instruments.[6]

Image via Gallica

Image via Gallica

Image via Gallica

Image via Gallica

Similarly, on a little artificial mount in a niche of Villa D’Este (Tivoli, Lazio – Italy), the Mannerist villa par excellence, one could see a fountain featuring an automated owl and a flock of birds. Through the action of the water, the birds were made to sing while the owl looked away from them. Yet, when the owl turned around, the birds immediately stopped singing. Nowadays, we think of an automaton as being a rather repetitive and uncreative object. This understanding emerged at the time of the Industrial Revolution, when the introduction of automated mechanisms began to raise questions about the difference between humans and machines as well as fears that mankind would have been supplanted by them. This was not the case in the 16th and 17th centuries. Indeed, as noted by scholar Jessica Riskin, who has conducted in-depth research about the cultural history of automata, such mechanical devices were conceived as unpredictable and capable of surprising the audience. There were all sorts of water games devised, for example, to spray water on the visitors, causing a commotion. A French noblewoman describes her experience with one such jeau d’eau in 1656 as follows:

As I passed through a grotto, they released the fountains, which came out of the pavement. Everyone fled; Madame de Lixein fell and a thousand people fell on her. . . . We saw her being led out by two people, her mask muddy, and her face the same; her handkerchief torn, her clothes, her oversleeves, in short, disconcerted in the funniest way in the world, and I cannot remember it without laughing. I laughed in her face and she started laughing too, finding that she was in a state to inspire it. She took this accident as a person of humor. She took no meal and went right to bed…Upon returning, I visited her: we laughed a lot again, she and I.[7]

Today, the term “grotesque” has shifted from indicating the wondrous, dream-like, disproportionate, and bizarre to evoking more macabre material, such as misshapen anatomical specimens. It is more associated with the disturbing than with playful imagination. Yet, in March 2017, the Grotesque made a return on the art scene at the Centre Pompidou (Paris) with the incredible Digital Grotesque project. The project consists of two grottos (Grotto I and Grotto II) entirely algorithmically designed and printed in 3D. The result is spectacular: endless surfaces of innumerable different sizes and textures overwhelm the visitor, celebrating again that union of technology and wonder that was once so valued by the artists of the late Renaissance.

Image via Digital Grotesques

[1] Vitruvius, quoted in Luke Morgan, The Monster in the Garden: the Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 51.

[2] Luke Morgan, The Monster in the Garden: the Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 62.

[3] Magnani, Lauro. Between Magic, Science, and “Wonder”. The artificial grottos of Genoese gardens in XVI and XVII. [Tra Magia, Scienza e “Meraviglia”. Le grotte artificiali dei giardini genovesi nei secoli XVI e XVII.] Editore: Sagep Ed.; (Genova), (1984)

[4] Antonio Pinelli, 2003. La Bella Maniera. Torino: Einaudi.

[5] Michel de Montaigne, Travel Journal, 64, quoted in Jessica Riskin, “Machines in the Garden” in Republics of Letters: A Journal for the Study of Knowledge, Politics, and the Arts 1, no. 2 (April 30, 2010). Accessed October 2017. http://arcade.stanford.edu/rofl/machines-garden

[6] Images from Salomon De Caus’s, “Book II – Problem XIIII” and “Problem XV”

[7] Anne-Louise d’Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier, quoted in Jessica Riskin “Machines in the Garden,” in Republics of Letters: A Journal for the Study of Knowledge, Politics, and the Arts 1, no. 2 (April 30, 2010). P. 42.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.