Finding Ferguson in Visual Culture

[Warning: this post contains violent images–Ed.]

I am striving to keep abreast on the struggles happening in Ferguson, Missouri. As a writer of historical and contemporary visual culture in the United States, I have found a lot of amazing work that addresses important issues on how to talk about privilege and race if you’re white, race and the police state, and the important role of photography as an activator in both the digital and print worlds. However, I have found little work that correlates the contemporary events in Ferguson with America’s not-so-deep and distant past. The murder of Michael Brown is another page in the American history of racist systemic violence. The photographs that document this atrocity are also to be understood as a crucial piece of our visual culture. To contextualize this particular past, I want to highlight lynching photography as a genre and as a starting point toward understanding how we view racist systemic violence through the cultural use of photography.

I have been hesitant to correlate the murder of Michael Brown to our nation’s past of lynching. I have been going back and forth on it for weeks. As a white woman who writes about death, I could not find any kind of entry point into this without trying to identify the history of this kind of photograph. Scrolling through social media feeds in recent weeks, I’ve been confronted with low-resolution images of Michael Brown’s body, lying on the pavement. His cheek is laid down on the pavement, his chin tucked in slightly. The stream of blood comes out from under him. This photograph has been posted and re-posted on my Facebook feed, printed in the newspaper, shown on television screens, tweeted, hashtagged, and shared in every way possible. The more recent video, and now audio, of his murder are also being shared across all mediascapes at an increasing rate.

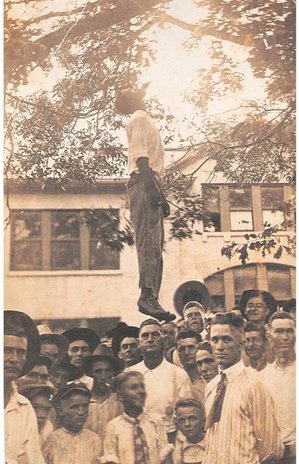

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines lynching as “to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal sanction.” As recent as the 1930s, lynching was still a violent reality that served as an unofficial warning to the black community and those that chose to be their allies. It was not uncommon to photograph someone who was lynched. These photographs were printed and disseminated, with many manufactured as postcards. They were meant to be viewed by local communities, both white and black, as well as dispersed. The images often captured a view of the entire body as it hung from a stationary point, which was often a tree. Many of these photographs show a crowd of onlookers. The faces of the living often gawk at the dead. Some are pointing and laughing, while some simply stare at what has happened in front of them.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines lynching as “to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal sanction.” As recent as the 1930s, lynching was still a violent reality that served as an unofficial warning to the black community and those that chose to be their allies. It was not uncommon to photograph someone who was lynched. These photographs were printed and disseminated, with many manufactured as postcards. They were meant to be viewed by local communities, both white and black, as well as dispersed. The images often captured a view of the entire body as it hung from a stationary point, which was often a tree. Many of these photographs show a crowd of onlookers. The faces of the living often gawk at the dead. Some are pointing and laughing, while some simply stare at what has happened in front of them.

There are other photographs where the crowd of onlookers looks back at you, the viewer. Their eyes meet yours as you look at this photograph. Many of these former gawkers are now dead themselves, and this moment in which they somehow participated in the death of another, whether actively or passively, is long gone. Their straightforwardness has a certain ownership to it, that they certainly did this act, and they might even be proud of it. The body that hangs above them is quiet and still, and gravity has taken over as the head and all limbs hang downwards. The sun, however, still shines, indicating that the day goes on and that this community, too, will continue onward even after this duty has been done.

Looking at this photograph, and all photographs of lynching, is very difficult. I might call is nauseating. It is a visual and visceral labor, and it is one that I feel through my whole body. Although I write a lot about postmortem photography, race, class, and death, I’ve spent very little time with photographs that show lynching. I have argued in many articles, conversations, theses, and casual interactions that looking at the dead is both uncomfortable and necessary because we must somehow deal with death if we are to approach it in a healthier way. Through all of this, I’ve managed to steer clear of this entire genre of photography because of the extreme discomfort that I felt. This is also a reflection of my own privilege, as I have chosen to step around a particular part of photographic history. I was able to enter into this historical context without really being forced to view it because I didn’t have to, it didn’t feel necessary, and lynching photographs are not as widely available as say, Weegee, who did photograph a lot of murdered white folks. Fun fact: “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” was shown at the International Center for Photography in New York. However, “Witness: Photographs of Lynching from the Collection of James Allen” was refused from ICP. [1]

Looking at this photograph, and all photographs of lynching, is very difficult. I might call is nauseating. It is a visual and visceral labor, and it is one that I feel through my whole body. Although I write a lot about postmortem photography, race, class, and death, I’ve spent very little time with photographs that show lynching. I have argued in many articles, conversations, theses, and casual interactions that looking at the dead is both uncomfortable and necessary because we must somehow deal with death if we are to approach it in a healthier way. Through all of this, I’ve managed to steer clear of this entire genre of photography because of the extreme discomfort that I felt. This is also a reflection of my own privilege, as I have chosen to step around a particular part of photographic history. I was able to enter into this historical context without really being forced to view it because I didn’t have to, it didn’t feel necessary, and lynching photographs are not as widely available as say, Weegee, who did photograph a lot of murdered white folks. Fun fact: “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” was shown at the International Center for Photography in New York. However, “Witness: Photographs of Lynching from the Collection of James Allen” was refused from ICP. [1]

I am using this cultural moment to become an active and engaged viewer, and to lean into the discomfort that I feel instead of avoiding it. As viewers of all forms of media, I can’t help but think that it is our responsibility to engage critically with visual culture as it is being presented to us. Viewing photographs of slain bodies not only emphasizes our mortality, but it allows us to directly engage with the troubling but necessary reality of racism and violence. While I don’t advocate for prolonged and constant glaring, there is something to be said for simply not looking away, not avoiding, or just taking a moment to engage with what (and who) you are viewing. To critically engage with the photograph of Michael Brown is to deconstruct and contextualize a long and difficult history of oppression, murder, and denial in America.

Lynching photographs provide a certain foundation for understanding of how we can begin to look at the photograph of Michael Brown. I urge you not to avoid this image or look away, but to spend some time with the last image of him, and to think about what Michael’s life means within the context of your community, both local and global. Lean into the discomfort that you feel when you think about the death of a young and charismatic teenager, and how the last photograph of Michael was not taken by his family, but by a stranger with a cellphone. Lastly, I ask: what does it mean for a culture to produce so many photographs of dead black men, surrounded by their murderers, who may be passive or active in their decisions, but who simply look back at you?

1. Dora Apel and Shawn Michelle Smith, Lynching Photographs. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). In my avoidance of lynching photographs, Iʼve also managed to avoid this particular work of my academic mentor, Shawn Michelle Smith. This is also a moment of appreciation for her.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.