Dunham the Dilettante

Lena Dunham, the now 30-year-old creator, writer, director, producer, and actress of HBO’s “Girls,” began her career making low-budget YouTube videos lampooning the art world, a realm wholly familiar to the daughter of painter Carroll Dunham and photographer Laurie Simmons. The satirical web series Delusional Downtown Divas for two seasons followed three young women artists in New York who attempt to schmooze, sneak, and coerce their way into the city’s art scene.

Lena Dunham, the now 30-year-old creator, writer, director, producer, and actress of HBO’s “Girls,” began her career making low-budget YouTube videos lampooning the art world, a realm wholly familiar to the daughter of painter Carroll Dunham and photographer Laurie Simmons. The satirical web series Delusional Downtown Divas for two seasons followed three young women artists in New York who attempt to schmooze, sneak, and coerce their way into the city’s art scene.

Delusional Downtown Divas (screencap by author)

In an episode of the second season titled “The Jonas Mother,” Oona, a budding writer, (Dunham) and Swann, a “private” performance artist (played by Joanna D’Avillez) visit iconic performance artist Joan Jonas (playing herself) under the pretense that they are journalists. Swann asks, “How do you know when you’re performing or when you’re just walking down the street?” Jonas responds, “First of all, you have to pretend you’re someone else, and you have to choose a persona. And you step from your so-called ‘real life’ into the life of the space of the performance.” In awe, Oona exclaims that she thinks this whole time she has also been a performance artist without knowing it. Encouragingly, Jonas asks, “Do you have a secret identity that you haven’t told anyone about?” Oona responds, “I’ve been working on a book, which is a first-person narrative about a person who’s like me, but different than me—because she’s had a boyfriend before.”

This meta-textual moment, layers upon layers of self-referential, satirical commentary on performance art, is a peek into a greater theme in Dunham’s work. Dunham’s 2010 film Tiny Furniture, her HBO series Girls, her two memoirs, and her venture into literary curation with the newsletter Lennyletter are all invested in not just promoting women’s art, but explicitly asking what it means to be an artist.

Dunham’s self-aware commentary on the inseparability of her personal life and the characters she embodies is not unlike the ways other women writers before her have described their relationship to their work. Emily Nussbaum has pointed out the literary tradition Dunham appears to be drawing from, or is closely aligned to—Dunham’s focus on art and privilege as two pillars of her work have much in common with the depictions of women in Mary McCarthy’s 1963 novel The Group, Wendy Wasserstein’s plays of the 1970s and 80s, Mary Gaitskill’s 1988 collection of short stories Bad Behavior, and the work of Sylvia Plath.

Dunham, like writers before her, is interested in critiquing the ridiculousness of hallowed art institutions, especially when it comes to women’s participation in them – and the way she does this is through depicting the creative process in her books, series, and films. By reinvoking the form of the Künstlerroman, a narrative about an artist’s maturity, Dunham is able to show how the perceived dilettantism of aspiring artists is in fact an integral part of their development as artists. Furthermore, in the way Dunham herself manages multiple professional ventures, she shows that dilettantism is an integral component of working in the contemporary entertainment landscape.

Tiny Furniture (screencap by author)

In the film Tiny Furniture, Aura (Lena Dunham), a recent film theory graduate from Oberlin College, moves back to TriBeCa to live with her mother, Siri (Laurie Simmons), and sister, Nadine (Grace Dunham). Aura is part of an emergent class of unemployed college graduates. The film, usually lumped in with the slew of micro-budget mumblecore films of the late 00s, serves as a valuable paradigm for exploring the struggle of a young middle-class artist. Tiny Furniture, essentially a domestic melodrama, attempts to neutralize objections to the characters’ privileged class status and renders Aura’s emotional vulnerability as a product of the country’s unwelcoming economy (it takes place post-2008 recession). By centering Aura in such a milieu, Dunham exploits the contrast between Aura’s mother’s artistic success and accompanying economic independence with the rather different problems of Aura’s economic dependence, which is masked as uncompromising artistic values.

In the film, Siri’s artistic legitimacy is not defined by its distance from capitalist economy but inextricably tied to her economic success. As struggling video maker Jed (Alex Karpovsky) remarks when he enters the loft, “It’s nice… It’s big…. It’s huge,” which he later equates with her “success” as a photographer. Even Siri’s productivity is placed within the framework of the art economy; she is preparing for a “big retrospective” in the coming year, which will undoubtedly help market her work to potential art buyers. Even Aura’s sister Nadine’s social success is measured by the “mainstream” appeal of her poetry. As a winner of a high school poetry prize, Nadine has gained recognition of her talent in the form of intellectual capital, which may serve to align her with the academic elite (largely white males from middle- to upper-class families). Though Siri inaccurately describes the prize as “the biggest prize you can get in the United States,” it is clear that Siri truly believes this is the case. Siri, unlike the vaguely modest Nadine, does not care about the specifics of the prize because artistic recognition is a prestigious prize, resulting in tangible social and economic rewards. The film seems to suggest that until Aura finds a way to capitalize on her art (by, as her friend Charlotte suggests, writing for Saturday Night Live or becoming a performance artist like “early Yoko Ono”), she will remain on the outside of family relationships, romantic relationships, and success.

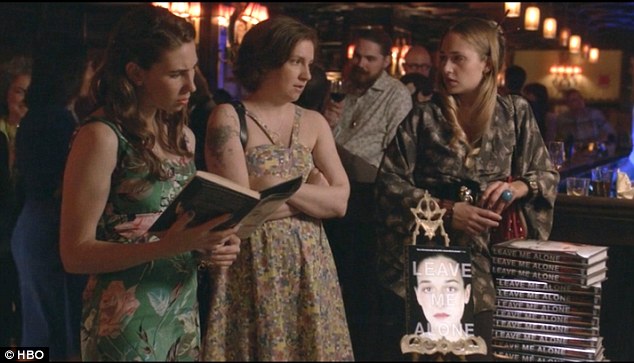

Girls book party (screencap via Daily Mail)

In “Girls,” the art itself is always bound up in commodities. In these characterizations, Dunham appears to be continuing the work she began in Tiny Furniture. Dunham’s attention to the ways market value changes the form, function, and utility of art is roughly sketched in the show’s early episodes. The first scene of season one’s episode, “Leave Me Alone,” introduces a ridiculous caricature of Hannah’s artistic counterpoint, Tally Schifrin, a published writer and former colleague who triggers Hannah’s insecurities. Tally becomes a symbol for how success can be attained by exploiting traumatic personal experiences, and the figure of Tally seems to question whether talent is as necessary as carefully constructed “authenticity” in the book world.

The introduction of characters like Tally Schifrin, Jonathan Booth (a comical conceptual artist), and, in season 4, the highfalutin writers at the voice criticisms of Hannah’s work akin to the real-life criticism directed at Dunham, are all figures through which “Girls” critiques the way “the personal” has become a commodity—one which Hannah willingly uses (and sometimes abuses) for her stories, while simultaneously valuing authenticity as a core ideal of the show itself.

Imbricated in the criticism of Dunham and her work is an implicit criticism that if Dunham is taking from her life—if she is the characters she writes—then her writing is an exercise in narcissism, and all her ventures are iterations of her “being herself” rather than inspired works of art produced through hard work. It is no coincidence that when German writers and aesthetic philosophers like Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe delineated the differences between a professional and a dilettante education (which was rarely available to women) and “objectivity” were important criteria. As literary historian Karin Wurst points out, “[The] historically established separation between art and dilettantism placed women in the latter group.”

Dunham has certainly been characterized as a dilettante, but her characters are more so dabblers in the arts. In the early seasons of “Girls,” Hannah bumbles from job to job, as do Marnie, Jessa, and Adam. They every so often take up singing, writing, painting, acting, and woodworking. But what reads as a sprawling and almost juvenile lack of direction eventually leads to more secure lives for them as their storylines begin to resolve in the end of season five.

In an interview with GoodReads, readers were asked to submit questions for Dunham. One reader asked, “You are a woman of many passions and have sought a variety of creative outlets over the years to express those passions. As a young woman starting out on her own creative journey I’m trying to balance all of the sporadic brain storming endless projects and it’s somewhat overwhelming. How would you advise balancing all these creative expressions in an impactful way and avoid becoming a chronic dilettante?” Dunham responded, “I think that there is a very old school idea we have to become a master in one medium but that’s continually being proven wrong by everyone from Oprah to Miranda July. Creativity is wonderfully amorphous! Let it take you where it will. Just try and finish what you start :).”

Indeed, the Jane-of-all-trades work ethic is especially important in the contemporary entertainment landscape where actresses, writers, and novelists are also models, perfumers, designers, and restaurant owners. However, for women multi-hyphenates, there is also a particular political implication in this kind of work. The self-preserving tactic of selling their personas, essentially to brand their selves (at least in large portion), speaks to the greater demands on women to monetize their private lives as well as their emotional labor in the face of a less-welcoming job market—especially in Hollywood. For Dunham, to write about writing, to portray herself as a writer, insistently makes strategic sense as a branding mechanism—authorship and auteurship have historically been useful to sell books and movies. However, it also has a more powerful resonance. In a sexist media landscape where female media makers are under constant threat of erasure, making women’s creative work visible across several platforms expands the reach of art and, hopefully, expands the ways people take it seriously.

Works Cited

Nussbaum, Emily. “Hannah Barbaric: Girls, Enlightened, and the Comedy of Cruelty.” New Yorker Magazine Online. 11 February 2013. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/02/11/hannah-barbaric

Wurst, Karin. Fabricating Pleasure: Fashion, Entertainment, and Cultural Consumption in Germany, 1780-1830. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2005. Print.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.