DIS/CREDITED

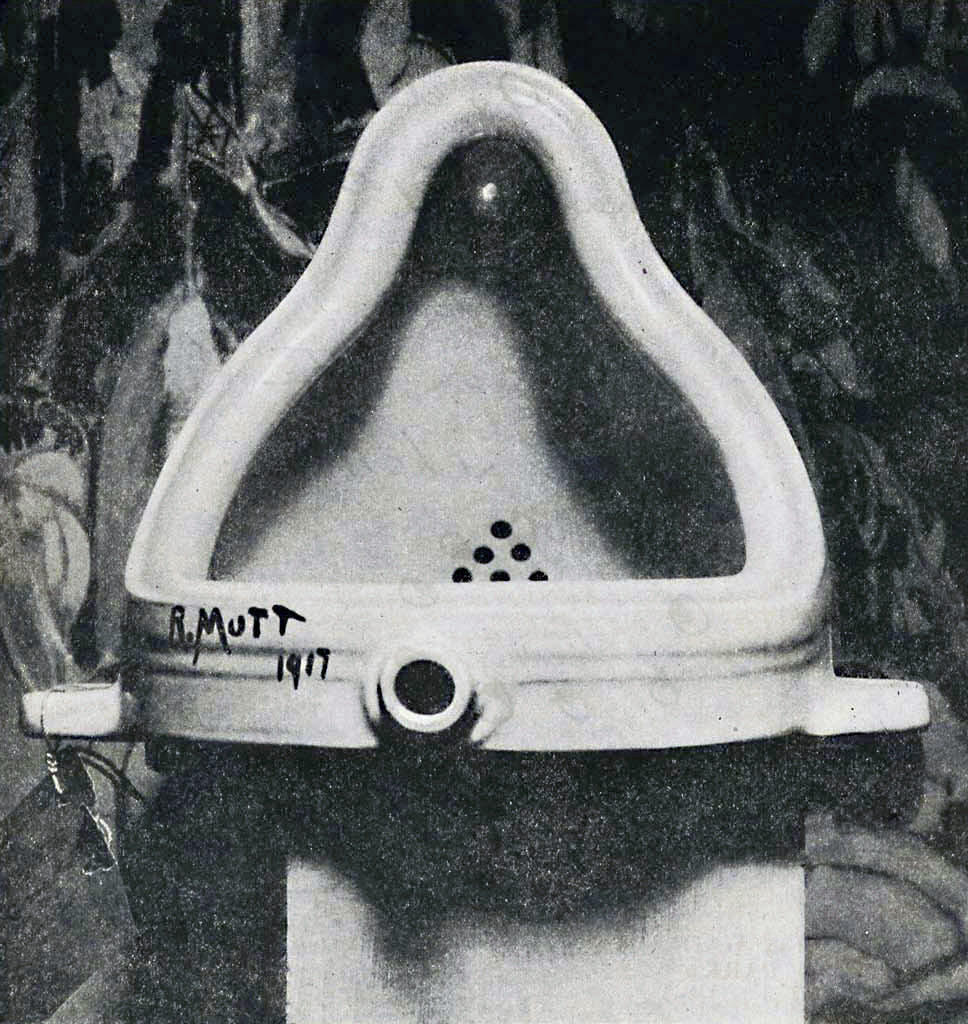

Fountain, attributed to Marcel Duchamp and photographed by Alfred Stieglitz. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

As the story usually goes, Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal with “R. Mutt” scrawled on it to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibition at The Grand Central Palace in New York. However, recent scholarship suggests that Duchamp’s notorious urinal readymade, Fountain, was actually submitted by one Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, herself a prolific Dada poet and artist.

In Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson’s 2014 article “Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?” in The Art Newspaper, the authors quote from an April 11, 1917 letter Duchamp sent to his sister recounting the notorious toilet: “one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”[1] The authors point to other evidence, such as the inexistence of the urinal model from the supposed manufacturer, the Baroness’s penchant for the scatological, and the similarity to her sculpture God (also of 1917), which had originally been attributed solely to a male artist (Morton Livingston Schamberg) but now also credits Baroness Elsa.[2] Spalding and Thompson demand that museums that present Fountain amend their wall labels and texts to include the Baroness. They write that the “public has a right to believe what it reads on a museum label.”

Getting the facts right, so as to not misdirect the public, is the great responsibility of the curator. A curator has to preserve the integrity of history. (After all, the etymology of curator is “care,” n’est-ce pas?) Spalding and Thompson recount that Duchamp did not start taking credit for Fountain until years after Elsa’s death in 1927. Apparently, he officially began taking credit for the work only after Alfred Stieglitz (the artist who photographed the work) passed.[3] Since those who would be able to officially correct the record were dead, it is up to curators, art historians, and researchers to advocate for Baroness Elsa, who died alone and in poverty under mysterious circumstances.[4] Duchamp’s name is cited in textbooks: the man who changed art with his toilet.

***

French philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre are often deemed the “intellectual power couple of the 20th century.”[5] Sartre is often credited with founding existentialism, while Beauvoir has been dis/credited for decades. In the book Beauvoir and Sartre: The Riddle of Influence, the essayists attempt to parse out the separate philosophical contributions of Beauvoir and Sartre in order to correct the record: “Beauvoir is still, unfortunately, not considered a philosopher in her own right.”[6] Most people do not know that Beauvoir’s novel She Came to Stay, which put forward the tenants of existentialism, was published before Sartre’s magnum opus Being and Nothingness. Sartre read her novel before he started writing his book, and yet he has been considered the philosopher and Beauvoir the muse.

Often, Beauvoir is thought about only in relation to her longtime companionship with Sartre and not as a philosopher herself. In his chapter “Beauvoir, Sartre, and Patriarchy’s History of Ideas,” Edward Fullbrook outlines “Ten Ways to Erase a Woman Philosopher.” Some of these include:

(1) “When in doubt about the origin of a woman’s philosophical theories and ideas, credit them to her closest male associate.”

(2) “When no longer in doubt about a woman’s contribution to philosophy, ignore the facts.”

(3) “Cite the woman out of context.”

(5) “Expunge the philosophical sections of the woman’s most-read work.”

(8) “Read the woman’s male partner’s fiction as philosophical texts, and then refuse similar readings of her fiction.”

(9) Ignore the woman philosopher’s gendered situation.”[7]

Shockingly (or not so shockingly), it wasn’t until 2011 that English readers could read the complete and unabridged translation of Beauvoir’s enormously influential The Second Sex, which was originally published in 1949. The new translation, by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevalier, amends the previous translation’s deletions of the book’s most important philosophical contributions. When the book was first translated into English and published by Knopf, Blanche Knopf made a crucial decision: “Thinking that this sensational literary property was a highbrow sex manual, she had asked an academic who knew about the birds and the bees…a retired professor of zoology” to do the translation: Howard Parshley.[8] Additionally, Alfred Knopf tasked Parshley with condensing the tome because Beauvoir “certainly suffers from verbal diarrhea.”[9] Ultimately, Beauvoir signed off on the translation, while also pointing to the omissions. Perhaps Beauvoir’s reputation as a sexual maven [10] had something to do with this strange view of her work, but most importantly, because her work was not regarded as significant philosophy by her publisher, her contributions to the history of ideas were minimized and almost forgotten.

In The Second Sex, Beauvoir challenges the reader to interrogate woman’s submission and the lack of reciprocity between genders. She asks: “Why do women not contest male sovereignty?” and “Where does this submission in woman come from?”[11] In considering Beauvoir’s reluctant acceptance of the mistranslations and omissions, these questions are crucial ones to consider. How did a revolutionary existential philosopher succumb to subservience?

“Up to now, I had made the best of living in a cage, for I knew that one day—and each day brought it nearer—the door of the cage would open; now I had got out of the cage, and I was still inside. What a let-down! There was no longer any definite hope to sustain me; though this prison was one without bars, I couldn’t see any way out of it. Perhaps there was a way out; but where? And when would I find it?”[12]

Beauvoir begins Part II of The Second Sex with “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.”[13] This sentence is monumental in a few ways, including that it is a clear existential statement and that it produces a new approach to philosophy: existentialism’s authenticity needs to account for gender and social position. This sentence also begins Beauvoir’s account of her own experience becoming woman—which she wrote about in her autobiographies. “In those days, people of my parents’ class thought it unseemly for a young lady to go in for higher education; to train for a profession was a sign of defeat.”[14] Ladies were supposed to be charming, elegant, and ornamental—good at making conversation but never provocative. “Humanity is male, and man defines woman, not in herself, but in relation to himself; she is not considered an autonomous being.”[15] Not only is woman determined by man, but she is herself “the negative, to such a point that determination is imputed to her as a limitation.”[16] Only men are self-determining.

***

As Nell Frizzell points out in her article “Duchamp and the pissoir-taking sexual politics of the art world” in The Guardian, “there is a difference between theft and misattribution.”[17] The problem is navigating the murky waters. As many other women have felt, it is anxiety-provoking and distressing to address issues of credit. Gaslighting is a common tactic (used consciously or not) to delegitimize women’s claims to authorship, power, and even their own experiences of being mistreated. Over time, this tactic of oppression can be internalized, causing cognitive and emotional dissonance when a person asserts their own agency. Or sometimes, it’s just easier to go along with it, stop fighting it. It is easy to tell women not to listen to the person putting us down or manipulating our perception. What is not so easy to do is to stop incorporating the skewed record. When your attempts to pursue your ideas are met with disbelief or even hostility, it is easy to succumb to feeling like an impostor: No, these thoughts were never mine. This work was not produced by my hand—it couldn’t have been! Of course I don’t deserve credit…

From early 2011 to late 2016, I was the editor and assistant director for an experimental radio project. I was present for the project’s first broadcast in January 2011 (although I did not organize it). For the first few years, I edited all the work texts and printed matter. I gave counsel on the project and wrote grant applications. I was an integral part in shaping the concept, style, and language of the project. Together, my collaborator and I chose artists and developed exhibitions and broadcasts. I was a full half of this team. Recently, the project has been honored with a mini-retrospective featured in an exhibition in a museum in New York.

A friend attended the opening at the museum and sent me a photo of the exhibition’s text. I had known the show was happening, but I was not included in its planning or execution: I stepped away from the project last year because of frictions in the partnership. However, since the exhibition covered the history of the organization, the imagery, texts, printed matter, and curations that I had produced and collaborated on were featured. My role in this organization/project, how it came to be and what it has done, was not described for the museum visitor: the only mention of my name was a small print photo credit, “Photos appear courtesy of Meredith Kooi.” I was not asked for any image permissions.

I took a couple of days and then I wrote to the curator. After all, I knew her. She had invited the collaborative project to a residency in 2015. Both myself and my former collaborator attended. I congratulated her on the exhibition and thanked her for including the project. I then suggested some corrections and amendments to the texts—not just for myself but also to ensure that others, without whose efforts the project would not have been possible, got their due credit. She responded, saying that she should have/could have contacted me and that the museum would reprint the wall text and amend the others. I thought, ok, this should go over fine. However, in the back of my mind I knew what was coming from my former collaborator.

The texts started coming in. He told me he read my email. He asked, “Why are you doing this?” I stayed firm in my position on my professional engagement and the credit I was due. He went personal. Telling me how I disappoint him. How he had even invited me to his wedding. How without him, inviting me to collaborate years ago, I would not have these interests and would not be making work in sound and radio.

I emailed the curator to check in on the edited text and asked her not to share my emails with my collaborator. She responded that she had not and that ultimately her contract is with him as a guest curator, so it’s all up to his approval. I replied that that was unacceptable. That there is ample public proof of my involvement with the project so I do not require his permission to be credited for my work. I didn’t hear from her for almost three weeks.

After not getting a response from her, I finally emailed, requesting an image of the wall text. It has an addition now: in small print at the bottom, a list of former and present collaborators was added, of which I am one. It doesn’t feel like enough.

The experience I’m describing is complicated. My collaborator and I had an intimate relationship. When he first came up with the idea for the project we were living together. In the beginning, it was unclear what sort of role I would play in the project. Was I simply the supportive girlfriend? Or were my contributions “worthy” of recognition? When I was eventually given the title of “editor,” my name was finally officially recognized. Even though my official position was “editor,” the work I did exceeded this title. I requested that we work out a new title. This request was not accepted kindly. With much convincing and prodding, my new role was codified: Editor & Assistant Director.

Throughout my years with the project, I have had the microphone taken out of my hand, been talked down to in front of artists and administrators we were working with, told that my ideas were irrelevant, and made to believe that this person—my former collaborator and lover—was responsible for my career, my ideas, and my work. In interviews he gave on the project, he usually left out my name, but whenever I gave talks about the project and my own solo work, I always credited him (both his solo work and work with the collaboration). In recent years, my collaborator has benefited from the project on an international scale. He has been invited to show work in exhibitions, give talks, participate in residencies, and other such opportunities—mostly sparked from contacts made through the project.

By no means am I equating myself with Beauvoir and Baroness Elsa. They are the greats and I am small potatoes. But both of these women’s work was seen as done in support of, or secondary to, their male counterparts. When the relationship is intimate, friendly or romantic, the lines between personal and professional support blur. This is when contracts should be written up—but that is not necessarily the first thing you think to do when working with someone you care about. In reading the wall text, I am confronted with how my role has been institutionally classified; it is a gendered and submissive one. I am left with little recourse—my former collaborator has sole control of this project now, so he writes its history, and I depend on his goodwill to include me in it. The museum has a contract with him for this exhibition and so uses the textual material he provides to them. Who can and should I appeal to? How many people should I risk offending by my persistence?

Whichever way you go, you’re screwed. Let it go, and you are erased. Stand up for yourself, and you are considered a difficult instigator. As an existentialist philosopher, Beauvoir was a proponent of radical freedom with responsibility, meaning that it is everyone’s responsibility to recognize and encourage the freedom in all others. But Beauvoir also writes that for woman, “the freedom she was granted could only have a negative use; it only manifests in refusal” and that “[c]hoosing defiance is a risky tactic unless it is a positively effective action; more time and energy are spent than saved.”[18] The “choice” is yours.

[1] Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, “Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?”, The Art Newspaper, Issue 262 (Nov 2014). http://ec2-79-125-124-178.eu-west-1.compute.amazonaws.com/articles/Did-Marcel-Duchamp-steal-Elsas-urinal/36155

[2] Morton Livingston Schamberg and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, God, 1917, wood miter box and cast iron plumbing trap, Philadelphia Museum of Art, http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51106.html

[3] Spaling and Thompson, “Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa’s Urinal?”

[4] Daughters of Dada: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven,” Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, http://www.francisnaumann.com/daughters%20of%20dada/elsa.html

[5] Dan Colman, “Lovers and Philosophers – Jean-Paul Sartre & Simone de Beauvoir Together in 1967,” Open Culture, http://www.openculture.com/2013/01/jean-paul_sartre_and_simone_de_beauvoir_together_in_1967.html

[6] Christine Daigle and Jacob Golomb, eds., “Introduction” in Beauvoir and Sartre: The Riddle of Influence,” (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 1.

[7] Edward Fullbrook, “Sartre, Beauvoir, and Patriarchy’s History of Ideas,” in Beauvoir and Sartre: The Riddle of Influence, ed. Christine Daigle and Jacob Golomb (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 123-6.

[8] Judith Thurman, introduction to The Second Sex, by Simone de Beauvoir, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevalier (New York: Vintage, 2011), xiii.

[9] Thurman, xiii

[10] Louis Menard, “Stand By Your Man: The strange liaison of Sartre and Beauvoir,” The New Yorker (Sept 26, 2005), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/09/26/stand-by-your-man

[11] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage, 2011), 7.

[12] Simone de Beauvoir, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (New York: Harper Perennial, 2005), 175.

[13] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 283.

[14] Beauvoir, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, 175.

[15] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 5.

[16] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 5.

[17] Nell Frizzell, “Duchamp and the pissoir-taking sexual politics of the art world,” The Guardian (Nov 7, 2014), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/nov/07/duchamp-elsa-freytag-loringhoven-urinal-sexual-politics-art

[18] Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 205, 724.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.