A Culture of Greed: 2008 in The Bling Ring and The Big Short

Since 2008 several critics have made the case for films such as Pain and Gain, The Wolf of Wall Street, Spring Breakers, The Great Gatsby, Blue Jasmine, and several other films as part of a genre cycle of cinemas of excess that interrogate the consumptive ethos at the center of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. But of all these films, two deal specifically with 2008: Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring and Adam McKay’s The Big Short. Though on the surface these two films have dissimilar subject matters, The Bling Ring and The Big Short are not entirely different. Both films use similar aesthetics to tell economic narratives through a pop culture lens. The Bling Ring’s underrated story is a quiet distillation of the economic ethos of millennials. In The Big Short the jargon of Wall Street and its values are relayed to the audience by celebrity cameos and montages of the era’s excessive pop culture. Like in The Bling Ring, in The Big Short popular culture is used as more than an atmospheric device used to orient the viewer to a specific time period; pop culture juxtaposes the time’s celebrity culture and the failing economy.

Writer and director Adam McKay’s Oscar-nominated film The Big Short follows a group of men who find a way to make profit off of banks’ risky lending practices. The Big Short is an amalgam of genres. A.O. Scott of The New York Times and David Edelstein at Vulture, among others, acknowledge the film’s hybrid form. Scott writes “A true crime story and a madcap comedy, a heist movie and a scalding polemic” and a “part business thriller, part stand-up comedy, with a liberal dash of NPR didacticism,” and it is this hybrid genre that keeps the film’s dynamic narrative propelling forward. The Bling Ring is also a composite, but of different materials. It is based on an article in Vanity Fair by Nancy Jo Sales, entitled “The Suspect Wore Louboutins,” about a series of Hollywood burglaries that occurred between October 2008 and August 2009. Although the film changes some aspects of the case, it attempts to depict the driving motivations for the teens of the Bling Ring (as they are called by media) to burglarize the homes of celebrities Paris Hilton, Rachel Bilson, Audrina Patridge, Lindsey Lohan and Orlando Bloom.

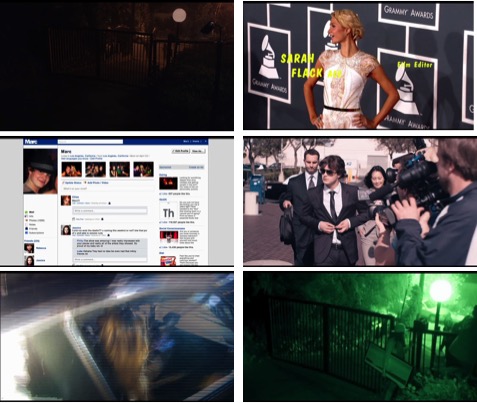

The Bling Ring is visually obsessed with celebrity, wealth, and things. Coppola suggests this obsession characterizes the American Great Recession of late 2007 to 2009. The film suggests that the media hypocrisy of selling seductive images of luxury goods to the crumbling middle-class is wrong and condemnable. The Bling Ring is not a satire–it is not a lampoon of the wealthy kids in the film, and that is what makes the film so troubling and so easy to misinterpret. The film is earnest in its belief that media and celebrity culture matters because it matters deeply to the young protagonists. By switching between 8mm, 35mm, webcam, stock footage, screenshots, and surveillance video, the film layers multiple forms of mediation.

The Bling Ring, screencaps courtesy of the author.

The collage style amplifies how the Bling Ring’s existence hinged on a confluence of media like YouTube, Facebook, reality television, and the rise of TMZ-style celebrity gossip in the late 2000s that prioritized the image for its intriguing mix of authenticity and artificiality. By frequently replacing smoothness with grain, blur, and washed-out filters, The Bling Ring recreates the dynamic image landscape that the teens of the Bling Ring so effortlessly navigated daily. Specifically, the repetitive intrusion of celebrity interviews and red carpet pictures into the diegesis establishes a parallel between the paparazzi culture of the late 2000s and the emerging selfie culture, where the teens themselves function as documenters of their every wardrobe change and club outing with the use of laptops and cell phones. The picture-covered Facebook walls of Rebecca and Marc are literalized as they walk up Paris Hilton’s stairs and see magazine covers featuring the heiress.

The Bling Ring, screencap courtesy of the author.

Various media do not only allow the teens of the Ring access to their favorite celebrities, but it also allows them to become like their favorite celebrities, cultivating glamorous personas and lifestyles on social media. For example, Paris Hilton and Audrina Patridge (of the MTV show The Hills) both cultivated their fame through reality television and tabloid culture, selling their lifestyles as not just an extension of a thriving career, but as their entire brand, setting a precedent that allowed, for example, the Kardashian sisters to become multimillionaire celebrities. In this sense, documentary style shooting, news reports, tabloid coverage, snapshots of social media pages, and webcam and security camera videos constantly interrupt the story and its cinematic style, contextualizing the events of the film historically.

The economic climate leading up to the financial crisis affected young people differently: whereas adults’ lives were upended, the lives of young adults was being more incrementally changed by a rhetoric that emphasized personal ambition and a meritocracy based on social media “likes.” The kids of the Bling Ring aspired to become brand names themselves, eager to make a compromise that conflated their selves with commodities to be bought and sold. The Bling Ring is about the teenage malaise that comes with “selling out”–not because they are not successful, but because their success comes with unattainable demands.

In a montage at the onset of The Big Short, the film juxtaposes the excesses of popular culture with the sobering reality of people losing their homes. These longer montages of popular culture images contribute to one of the film’s arguments: the culture of excess of Wall Street is intimately tied to the excesses of popular culture.

The Big Short, screencaps courtesy of the author.

Thus, McKay’s use of celebrity cameos to explain terms like “credit default swaps” and “collaterized debt obligation” is more than a quirky aesthetic disruption to the story. It is using the very means by which economic systems sell dreams of fame and fortune: celebrities, movies, fantasy. McKay’s assertion is that the cameos infused the film with levity and irony. In an interview with the New York Times, McKay asks, “Like, what would happen if that pop world actually told us real information? If Kim Kardashian was being filmed on TMZ and stopped and talked about the Libor rate scandal, what would that do to us?” The film’s persistent use of celebrity suggests it is difficult to discern the “reality” in the fabricated and stylized images of pop culture.

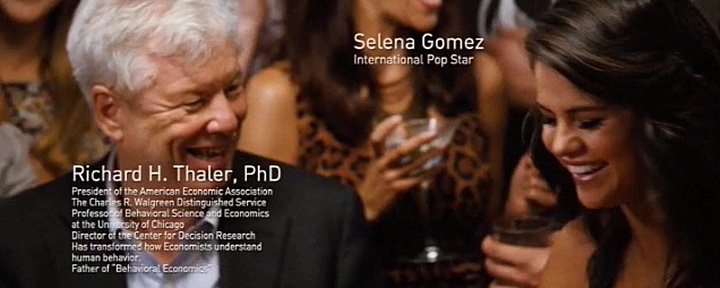

The pop culture figures who intrude into the diegesis are, for the most part, niche and contemporary to now, not to 2008: post-Wolf of Wall Street Margot Robbie, celebrated chef Anthony Bourdain, and Selena Gomez in her current pop-star reincarnation.

Margot Robbie in The Big Short, screencap courtesy of the author.

Anthony Bourdain in The Big Short, screencap courtesy of the author.

Selena Gomez in The Big Short, screencap courtesy of the author.

These fourth-wall-breaking interjections do not quite have the effect of a lecture on Libor by Kim K on TMX might have, because these moments are still illusory. They do not quite function as direct address, which oftentimes works in film to break the illusion. Robbie in a bathtub, Bourdain in a bustling kitchen, and Gomez having a ball in Vegas alongside a renowned economics professor suggest that although 2008’s pop culture landscape was oblivious to the shifting economic landscape, current pop culture figures benefit from pop culture’s political attunement to prove their cheeky knowingness in cameos such as these.

A passing but integral reference in The Big Short is MTV’s reality show The Hills, the oft-maligned Laguna Beach spin-off starring Lauren Conrad. Its use in The Big Short also coincides with The Bling Ring’s suggestion of this show as a symptom of moral decline–one of the Ring’s targets is one of the stars of The Hills, Audrina Patridge. In both films, The Hills seems to be visual shorthand for the excesses of 2008. The show revolved around the lives of well-off twentysomethings who (supposedly) did not feel the forthcoming pressure of the financial crisis (The Hills was even more explicitly referenced as thus in Season 4, Episode 8 of HBO’s Girls).

Discussing The Hills in The Big Short, screencap courtesy of the author.

But its brief appearance in The Big Short suggests it is far more than an out-of-touch reality show, or even a symbol of the times. Both films interrogate mediation and objectivity–in The Big Short the stakes are higher, for more people, but nevertheless McKay is interested in the disjuncture between what’s happening in real life, on Wall Street, and in pop culture. In The Bling Ring, the teens live out their lives as though they are in music videos, essentially living for their cell phone cameras. As a hybrid show in which it is unclear where the actor and “real person” begin or end, The Hills is a distillation of these serious questions, and it is significant that both films use The Hills as a touchstone to suggest as much. In doing so, The Bling Ring and The Big Short show how the use of celebrity images, as a central or peripheral device, is important to re-creating the ethos of a time period.

Both films make a compelling case for 2008 as a crucial turning point in the public’s relationship to media that is also seen in other films about that year. In the film Affluenza, directed by Kevin Asch, 2008 is also marked by a changing relation to media pre- and post- recession. Like in The Big Short and The Bling Ring, media provided a dose of reality after the financial crisis as well as glossy images of the elite. Taking place quite literally on the cusp of 2008 and 2009, Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station viscerally depicts the turn in the primacy of the image. In the film, which dramatizes the true story of Oscar Grant’s murder, cell phone and video cameras become a new and powerful mode for disseminating news. These films suggest 2008 was a moment where images regained their trustworthiness by the very fact that news, advertising, magazines, and other image-makers toned down their sensationalism, if only temporarily. The Hills was cancelled, the era of Paris Hilton passed, the era of the public celebrity breakdown passed, fashion became less about visible labels, and even social media images trended toward minimalism. In The Big Short and The Bling Ring, 2008 is significant because of the events that happened that year and also because that year frames how we see and use media today.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.