Critical Feelings: A Primer on Emotional Culture

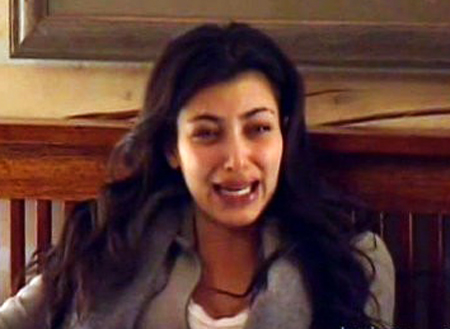

It’s Kim Kardashian’s ugly cry face. It’s pop music where men croon to you about wanting to be your boyfriend and woefully lament you breaking their heart. It’s the recent photo essay/internet phenom, My Wife’s Fight with Breast Cancer. It’s the single lens through which all these things can be viewed. It’s a national phenomenon. It’s emotional culture — and proof that “post-9/11” is just a myth.

I want to provide a critical grounding for what emotional culture is and why it’s relevant to cultural studies and criticism. I want us to understand that we inhabit an emotional culture, instead of distancing ourselves from it. I want us to view culture through the lens of emotion. I want us to embrace a critical emotional theory, understanding that there is no such thing as criticality without emotion.

The last decade or so has provided fertile ground for growing this emotional culture. 9/11 marked a pivotal moment in the American cultural landscape, prompting new outgrowths of affected culture – that is, culture steeped in and infused with the complex, nuanced emotional qualities one might expect after a severe psychic trauma. The fields of trauma studies and clinical psychology have explored how we process trauma, suggesting stages where we establish safety, mourn and remember, and eventually reconnect with others. Additionally, the field of affect theory suggests that felt experience is in itself a source of knowledge. Combine these areas of interest and voila! We’ve set up a framework in which emotional culture can exist.

But how did we get here? The stark aftermath of a nation reeling post-trauma was the perfect atmosphere for intense emotionality to flourish. The country was proved to be vulnerable, exposed – and, as it struggled to establish a necessary sense of safety, reactive. Mainstream political discourse got hotter, anxieties about everything from obesity to terrorists multiplied, and mass culture got…feely. Some examples from just the last few years: the impassioned Occupy movement, the rage-fueled, fed-up fury of Slutwalks across the globe, and, of course, the boundless success of Adele’s weepy 2011 hit, Someone Like You.

And it’s bizarre, right? Because we live in a culture that is on many levels reticent to engage with emotion. Emotions are messy and unpredictable, often resistant to tidy resolution. They make us feel weak and vulnerable when we express them. They make us feel, which reminds us that we are human. They remind us we are indeed mortal. They remind us that we end, which makes us afraid, which makes us react.

Yet, since 9/11, mass culture has become, undeniably, deeply saturated in the dramatic affective vocabularies of trauma: fear, love, hate, loss, and rebirth, just to name a few. The same culture that vehemently scorned Kim Kardashian for her unattractive, contorted cry face is the same culture that responded in earnest to the pain and grief conjured by Angelo Merendino’s intimate photographs of his dying wife. These images are potent in the context of emotional culture for the feelings they themselves suggest, as well as those they inspire in the viewer — namely, vulnerability and loss. These images could not communicate in mass culture in this way if we had not developed this sixth sense: critical emotionality.

Never mind our complicated spectatorial relationship with beauty – Merendino’s photos are rich and visually beautiful and the grainy Kardashian photo in question is not, so part of the allure of Merendino’s images is their craft. Artfulness or lack thereof aside, each image makes us churn in different ways as we view; each image generates a felt response. On some level, felt culture — emotional culture — is death culture. Death, too, is unpredictable, possible at any moment. But on the other hand, we know it’s definitely coming, a tidy resolution in itself. Therein lie the tense relationships we have with emotion and mortality — we want to be alive and to feel, but that is pretty scary business a lot of the time. How we engage with the prospects of death, tragedy, and loss is a great barometer for how we process the daily, ongoing ebbs and flows of emotion, which then infuse culture. What so-called “post-9/11” culture highlights is the spectrum of felt response that bubbles up into culture, because we are culture. And we’ve got so many feelings.

Never mind our complicated spectatorial relationship with beauty – Merendino’s photos are rich and visually beautiful and the grainy Kardashian photo in question is not, so part of the allure of Merendino’s images is their craft. Artfulness or lack thereof aside, each image makes us churn in different ways as we view; each image generates a felt response. On some level, felt culture — emotional culture — is death culture. Death, too, is unpredictable, possible at any moment. But on the other hand, we know it’s definitely coming, a tidy resolution in itself. Therein lie the tense relationships we have with emotion and mortality — we want to be alive and to feel, but that is pretty scary business a lot of the time. How we engage with the prospects of death, tragedy, and loss is a great barometer for how we process the daily, ongoing ebbs and flows of emotion, which then infuse culture. What so-called “post-9/11” culture highlights is the spectrum of felt response that bubbles up into culture, because we are culture. And we’ve got so many feelings.

Given all this, I question the term “post-9/11” as it is often used in mass media. Frequently, it implies something like “after emotionality” which we know is an inaccurate assessment of where American culture is today. Felt experience (particularly in the wake of trauma) is not something that can be neatly ordered and categorized for ease, and often resilience comes directly from that messiness. We’re not “post-9/11” and that’s okay. Rather than repress our fears and anxieties, we ought to just get emotional already – not to mention acknowledge how emotional we’ve been! It’s time we embrace the exciting, unmapped terrains of emotionality, without eschewing the critical lens necessary for making and interpreting culture. We should understand, once and for all, that critical thought and feely feelings are actually natural best friends. It’s time we embrace our emotional culture.

UPDATE: To read a response to this article, click here.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.