Instagram and Protest: Cake in the Imaginary Economy

Like pets, babies, and Beyoncé, cake has become a trending post type on Instagram. Cakes and baked goods are regularly shared via social media, highlighting their fat stacks, clean layers, or eye-catching decoration. In addition to gathering followers and creating new trends, these types of images also create a community of bakers and pastry chefs that learns together, building on techniques and flavors. An Instagram account like Drake on Cake (@drakeoncake), which takes Drake lyrics and puts them atop cakes via frosting, is humorous, but other cake-decorating accounts are more politically driven. After all, cake has become a point of political policy: the Supreme Court heard a case in December 2017 (Masterpiece Cake Shop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission) that centered on a baker’s refusal to make a wedding cake for a gay couple’s wedding celebration.

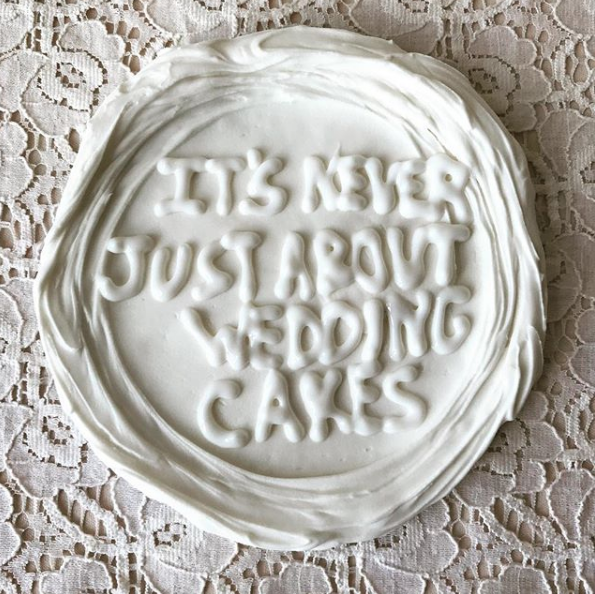

In joining the movement resisting the Trump administration, accounts like Protest Cakes (@protestcakes), connects to marches and protests across the United States. Protest Cakes creates cakes laden with meaning, often related to specific protests at hand, and works to motivate followers to continue to protest and remain active. The idea of using cake as a catalyst for change and as a form of protest is at once captivating and confusing. Cake, it seems, is ephemeral, temporary and brief in its joy before being consumed. We would hope that the need for protest is likewise temporary and soon resolved. If cake is an ephemeral object, where is its role as a visual object, particularly in times of protest?

According to the founders of Protest Cakes, Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, cake is the best way for them to highlight issues they are passionate about and find ways to address them. As pastry chefs and artists, the pair believe that “a cake is meant to be shared” and found this project as a way to share their dissent.[1] When creating Protest Cakes, both believed cake to be “a great medium for expression, especially on Instagram, but [they] really wanted to share delicious cake with all of the people doing the hard work of democracy.”[2] As pastry chefs, cake became their way of building action and creating change.

Protest Cakes began when Wilson and Rosenberg decided to create a cake based on political issues they were passionate about. The first cake related to the travel ban and was made on February 4, 2017. (Leah Rosenberg left Protest Cakes a year later on February 4, 2018, but their collaborative body of work will be considered here.) Constantly in conversation, the two of them periodically come up with a concept or issue that has been in the news and create a cake that relates to the message. With ingredients often donated by friends, the women set about to create cakes that relate to a social justice issue or a policy change enacted by the Trump administration, and they decorate the cakes with related text in frosting, encouraging their followers to take action.

For instance, their Contraception Cake was made in protest of birth control protections in danger of being rescinded by Republican congressional representatives. Their Instagram post was a photograph of a cake that was made with “ingredients used around the world to prevent pregnancy before reliable contraceptives became available.” It was topped with white frosting and decorated to look like a birth control pill packet.

Other cakes use the same method, drawing attention to a particular issue through recognizable artistic decoration and physically made of ingredients that also relate. Their cakes protesting the immigration ban, dubbed Seven Nation Cake and Six Nation Cake, contained ingredients from all the countries banned: ingredients were written on miniature squares of paper that look like protest signs attributed to their respective countries, and stuck into the cake with toothpicks. Another cake, Smog Cake II, was made in protest of the appointment of Robert Phalen as an adviser to the EPA, and features Martha Stewart’s Cloud Cake topped with a suffocating-looking gray cloud of charcoal cotton candy.

At once captivating and appetizing, Rosenberg and Wilson share more information about the cake in the caption. For Contraceptive Cake, they shared the ingredients, such as honey and neem, and their origins in regions where these ingredients were used as contraceptives (Egypt and India, respectively). Other captions might share the location of the site where the cake is headed, so that viewers near that location are encouraged to attend that local protest. And often, if there is no protest where the cake is going, there is also information with phone numbers to call, senators to contact, and names of bills to support or reject. Protest Cakes situates itself at the crossroads where protest, art-making, and food culture meet.

PROTEST

Wilson and Rosenberg have described their practice as “political pastry” or “cake-based activism,” combining their formal artistic knowledge with their practical experiences as pastry chefs. Cake has always been present in both Protest Cakes founders’ artistic practice and careers

After the 2016 presidential election, like many people, the two pastry chefs thought about how they could personally use their skills to inform others about issues they cared about. They found that cake-based activism was what worked best for them. As they explain, “cake is the best way for the two of us to share ideas, causes, concerns, and celebrations with the world.” They go on to clarify that making cake isn’t the only way in which they pursue activism against political policies they disagree with, and that that cake making works in conjunction with more straight-forward actions such as calling their representatives. For them, adding cake into their activism allows for widening their political activity in hopes of inspiring others to do the same. And as in protest, they work in the belief that “that cake brings people together…it is a shared experience.”[3]

With almost 3,000 followers, their cake making is certainly a shared experience, if followers do not often share the actual, physical consumption of the cake. On Instagram, viewers interact with the photographic replication, its caption with detailed information, and make meaning from the two elements. As Jenny Herman says in her article ““#EatingfortheInsta: A Semiotic Analysis of Digital Representations of Food on Instagram,” “This process of making meaning creates the sense of being an insider, which allows for inclusion in a familiar experience” that represents “a cultural moment in which the Instagrammer played a part.”[4] This allows connections to be made. but while it “strengthens new social ties, it paradoxically pushes the culinary world to a visual space beyond the act of eating.”[5]

In this way, Protest Cakes, and more generally, social media, begins to create a community of followers that are interested in staying informed and instigating change. However, this is a cause of concern: activism via social media can commodify social justice, allowing a viewer to passively consume content. But Protest Cakes invites viewers not only to bake but to #callourreps, distributing necessary information along with visual pleasure. One square image can only show so much. Social media can be used to educate, share and disseminate new ideas, and hopefully to help inspire. And isn’t that what making any kind of art is about?

ART MAKING

Leah Rosenberg considers creating and sharing cakes in conjunction with her artistic practice. While in graduate school, completing a thesis on the artistic possibility of cake, she began cake-decorating classes as a way of learning outside of the academy. She would often bring the cakes to her art critiques and exhibitions, which led to responses that became a part of her artistic work as well. As she explains in an interview about her artistic process:

I loved the response. It was the response I wanted when someone looked at one of my paintings hanging on the wall. As I continued to bring cakes to class, I paid attention to the response. I started to think about what cake does and if painting can do that— can a painting be generous? I was also thinking a lot about the different aspects of consumption involved with cake and painting. With cake there is an end— it gets eaten or it rots. There is no end to a painting. It hangs on the wall for constant judgment.”[6]

But if, like Rosenberg says, cake has an end, how do we archive it? For Protest Cakes, the cake’s photographic image lasts for time eternal (or whenever Instagram becomes passé). By capturing the cake’s nature and image, the cake becomes an object of protest and archived digitally for use and re-use.

Protests, art, and cakes are receptive. Like the image, protests and cakes are dependent upon audience response and, ultimately, consumption. Theorist Allan Sekula writes about the image and the archive, likening the archive to a toolshed. He says, “an active archive is like a toolshed, a dormant archive like an abandoned toolshed.”[1] If we are to take this metaphor and apply it to this particular example, Instagram becomes the toolshed, an archive that is dependent upon activity to remain relevant. While this account gains followers and the hashtag #protestcake is used, the movement also remains active. With hashtagging and the constant act of making, this Instagram account is continually generating new work to engage its followers. It is an active archive, at once creating a body of work, an archive of cakes but also preserving what is happening in real time, politically.

EPHEMERA AND THE ARCHIVE

Like the image, protests and cakes are dependent upon audience response and, ultimately, consumption. In many ways, Protest Cakes MUST be a visually driven project, as cakes are temporary. How do we record, archive, and organize when the news “has been coming faster than we can bring butter to room temperature?”[7] The cake functions as a physical object (like a protest sign), but it will be consumed and disappear unless an image is reproduced to archive.

Because Instagram can house our images in a single, curated account (Instagram Stories aside), a narrative and an archive build over time. The account becomes an archive, both of the cakes made and also of moments of public crisis over gun rights, reproductive rights, national monument statuses, and countless other threats. The image of the cake begins to function as a memorial—the Protest Cakes feed is a record of events, an archive of various angers and the efforts they engender. When we archive something, we are preserving a time and place but also, in a way, protecting. We are protecting a moment to be used in a future context. How will we see this resistance movement in the future? And perhaps more importantly, how will we be able to use this moment in time to further propel change as we leap and bound forward?

Protest Cakes is a prime example of what theorist Allan Sekula calls “the ways in which photograph constructs an imaginary economy.”[8] In our contemporary environment, photographic culture bleeds into our everyday life with the almighty presence of social media. As our reality is often mediated via images, new economies are formed as we place new values on images we see on our screens. “Photography constructs an imaginary world and passes it off as reality,” thereby creating its own economy where the image and its temporary escape from reality offers new and different items of value.[9] Instagram followers are most likely not going to consume the actual cake and its physical flavors. Instead, they will be consuming the image: the photo’s value is imaginatory, with that comes potential. The photo of the cake becomes a potential for growth and expansion, to encourage others to remain active, and to potentially drive change for the image’s featured issue. In this imaginary economy, the image of a protest cake becomes a catalyst of change and a powerful token of exchange in world of Instagram.

FOOD CULTURE

When asked about the future of Protest Cakes, Rosenberg and Wilson ask back, “but also wouldn’t it be nice to know there was an end?”[10] That may be the hope, that there be a time when protesting is no longer necessary, when justice is achieved. Rosenberg and Wilson know that this, perhaps, is impossible. Their hope for the future would be that “for seven days we could become Celebrationcakes, and then go back to protesting all the other issues that need to be addressed.”[11] So like the creation and capturing of ephemera and the archive, this argument, these protests, and cakes made against bigotry, can be a generative process for future protests yet unrealized.

Ultimately, these cakes, the artistic practice of making them, and the protests they are a part of converge to continually create a generative archive of work. As cake is shared, so are the images, and protest as well. Can cake make us think about protest as something to be shared, as something as generous as cake? As Leah Rosenberg asks, can a painting be generous? To take that one step further, is art generous? Can protest, like cake, be generous?

[1] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email correspondence with the author October 23-November 25, 2017

[2] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email

[3] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email

[4] Jenny L. Herman. “#EatingfortheInsta: A Semiotic Analysis of Digital Representations of Food on Instagram,” Graduate Journal of Food Studies 4, no. 2 (November 11, 2017): https://gradfoodstudies.org/2017/11/11/eating-for-the-insta/

[5] Jenny L. Herman, “#EatingfortheInsta: A Semiotic Analysis of Digital Representations of Food on Instagram”

[6] “Leah Rosenberg,” In the Make: Studio Visits with West Coast Artists (blog), April 2011: http://inthemake.com/leah-rosenberg/

[7] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email

[8] Allan Sekula, “Reading an archive: photography between labour and capital,”in Visual Culture: The Reader, ed. Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall (London: SAGE Publications, 1999), 182.

[9] Allan Sekula, “Reading an archive: photography between labour and capital,” 182

[10] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email

[11] Leah Rosenberg and Tess Wilson, email

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.