Anxiety in Real Time

Historically, women’s experience has been ridiculed, disbelieved, and dismissed. Similarly, many advertisements for women present not actual women’s experiences but rather a constructed stereotype that relies heavily on old patriarchal ideals of how women should be depicted. Many ads are highly refined consructions that exploit cultural anxieties about feminine norms—for example, that women, animalistic and insatiable by nature, must control their appetites for food and sex. Women’s visual presentation must be as decorative as possible; animal urges are unseemly. If you have ever seen an ad aimed at “women,” but thought to yourself, “I literally know no women like that,” then read on.

Sometimes it is difficult to ignore the lived reality I experience as I research. What began for me as a piece about unpacking advertisements featuring shameful (and shaming) caricatures of women turned into an undeniably embodied adventure as I watched, listened to, and looked at dozens of ads for everything from diet yogurt to couture fashion. Because I knew I wanted to write critically about this content, and in order to prepare myself for the onslaught, I also (finally) read Naomi Wolf’s landmark book, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women, as well as some other potent and relevant feminist theory, like Susan Bordo’s Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and The Body; and Elizabeth Grosz’s Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism, so I will use some references to those works, too. Because really, what better way to apprehend the meaning of “…[the] body is the instrument by which all information and knowledge is received and meaning is generated” than to subject one’s own body to viewing ten consecutive Special K commercials? 1

At every turn, the same themes seemed to greet me, regardless of the product or company responsible. In a day of listening to the radio or browsing the internet, I was able to get a distinct sense of women’s incorrigible behavior. However, at the same time that women are derided for being too sensual, we also encounter a barrage of marketing that refigures and reinforces notions of feminine sensuality to sell its products. At the same time that we are urged to strive for coolness and casualness as the ideal expression of feminine attractiveness, we are bombarded with notions of “obsessive” and “addictive” femininities as they relate to shopping, sales, makeup, and rich desserts (as though that is our nature).

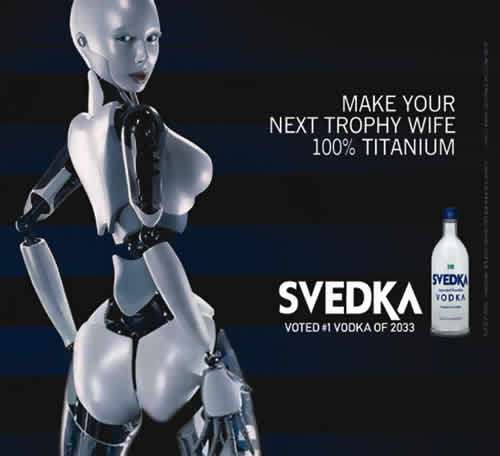

Patriarchy needs to depict women in a particular manner in order to sustain itself. By addressing women in this degrading way, many ads function as a vehicle for the maintenance of the male-dominated status quo—after all, it is much easier to dismiss a woman with the image of a one-dimensional make-up addict in our minds than, say, with an understanding of women as robust, dynamic, and complex. As it produces and capitalizes on the fears of and anxieties about women’s interests and desires, our visual culture serves as a rapidly deployable tool to maintain control—not to make known the myriad experiences and tastes of real women. Most of us know to be skeptical—at least to at least some degree—of the blatant sexism in the image of an incompetent female driver or a certain pornographic vodka robot. But what about more recent, less overt, and therefore more pernicious tropes that on some level acknowledge women’s autonomy but simultaneously undermine it? Spoiler alert: no less maddening. In this ad, for example, TJ Maxx asks women if, despite the pressures of adulthood, they have made fashion choices that “stayed true” to their once-uninhibited selves. Cloaked in the rhetoric of choice and authenticity, this ad suggests that a confident, modern woman knows how to effortlessly choose the correct pieces that represent her ethos. Now, I love fashion and admire anyone who really knows how to put a look together. But this commercial does not question women’s frequent status as visual objects, nor does it venture that perhaps some women learn early that having the right look is a social currency. Instead, it reframes the expectation of women’s adornment into an exercise in presenting the “authentic” self. Again we are told to put in the effort but never let it show.

Most of us know to be skeptical—at least to at least some degree—of the blatant sexism in the image of an incompetent female driver or a certain pornographic vodka robot. But what about more recent, less overt, and therefore more pernicious tropes that on some level acknowledge women’s autonomy but simultaneously undermine it? Spoiler alert: no less maddening. In this ad, for example, TJ Maxx asks women if, despite the pressures of adulthood, they have made fashion choices that “stayed true” to their once-uninhibited selves. Cloaked in the rhetoric of choice and authenticity, this ad suggests that a confident, modern woman knows how to effortlessly choose the correct pieces that represent her ethos. Now, I love fashion and admire anyone who really knows how to put a look together. But this commercial does not question women’s frequent status as visual objects, nor does it venture that perhaps some women learn early that having the right look is a social currency. Instead, it reframes the expectation of women’s adornment into an exercise in presenting the “authentic” self. Again we are told to put in the effort but never let it show.

Nothing about any of these women is casual—they must be fixated on something at all times, in a perpetual state of lunatic obsession. Despite the pressure for women to be effortless and cool, in this construction, women can never be so. It’s an impossible expectation. I don’t know if Alana Massey was thinking about Bordo when she wrote “Against Chill,” but I think they would have a lot to talk about.

Nothing about any of these women is casual—they must be fixated on something at all times, in a perpetual state of lunatic obsession. Despite the pressure for women to be effortless and cool, in this construction, women can never be so. It’s an impossible expectation. I don’t know if Alana Massey was thinking about Bordo when she wrote “Against Chill,” but I think they would have a lot to talk about.

Some commercials employ delightfully absurd attempts at self-reflexivity. A tactic that advertisers have come around to within the last 5-10 years is to critique the manacles that bind women to our rigorous routines of unrelenting internalized abuse. The most notable example is Dove’s dubious Real Beauty campaign. However, even as companies gesture toward some kind of awareness of the multi-million dollar miasma to which they contribute, they still talk down to women. One Special K commercial refers to the brand’s low-fat granola as “a taste of freedom” from the tyranny of dieting. Are you kidding me? Low-fat granola is not freedom. Being able to walk down the street without fear of rape would be, though. Is there a cereal for that?

It is key to consider how ads, broadly speaking, function. Bordo asks us to think about advertising as a kind of “gender ideology” that perpetuates difference and inequality.2 That is, rather than show viewers our common humanity, advertisements teach audiences what it is to be a woman. Advertising constructs a one-way interaction with women viewers as part of a constellation of mass-cultural messaging that forecloses on our sense of possibility and potential in order to keep us in our place. Advertising epitomizes the push towards a familiar script of fears that, if left unchecked, those voracious appetites threaten the stability of life as we know it. Moreover, this messaging demonstrates inequity when held up against the notions of rational freedom that men enjoy. Preferably, advertising would employ an improvisational approach that allowed women the full range of exploratory humanity. What would it be like to see more of ourselves reflected back to us by mass visual culture, to look around us and see wit, creativity, fearlessness, and kindness? My suspicion is that it might help give us a little more room to breathe, to imagine. Instead of the beloved national pastime of making light of women, perhaps a visual culture that honored our ambition and achievement could shift us away from chronic anxiety and into a new era of possibility. A taste of freedom, indeed!

What would it be like to see more of ourselves reflected back to us by mass visual culture, to look around us and see wit, creativity, fearlessness, and kindness? My suspicion is that it might help give us a little more room to breathe, to imagine. Instead of the beloved national pastime of making light of women, perhaps a visual culture that honored our ambition and achievement could shift us away from chronic anxiety and into a new era of possibility. A taste of freedom, indeed!

1. Grosz, E. A. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994. p. 87.↩

2. Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley: University of California, 1993. p. 110.↩

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.