Grief and Undoing

We are all going to die. For most, avoiding the topic is easy. We live in a culture that encourages the living to move forward with experiential blinders, avoiding the dark, and the depressing, and the morose. It is this particular affective distance that creates and maintains basic barriers between the living. In short, it isolates those that have been affected by loss.

I write and talk about death openly and earnestly, and there always comes a point where I am asked how I came to this work. My subjects and readers see my youth, privilege, and buoyant demeanor, and they infer that I chose to work on death because I am secretly ill or somehow damaged. What is not apparent is my struggle to cope with the loss of a friend and partner who represented so much more to me. And when I first started my work around death, I stumbled forward in an attempt to make sense of this tragic loss. I was able to identify death as a critical topic when considering what my ideal relationship could be with other human beings.

Talking about death is a radical and political act because it works to subvert our daily social structures that teach us to turn away from these difficult conversations. I want to help others communicate about death. I want to help them learn in a more gentle way what felt so disruptive and painful for me: death is real, around us, and accepting it allows us to better humanize others, find deeper capacity for generosity, and express with more intimacy our appreciation for what and who we love.

My work is my own way of pushing against the culture I grew up in, which mourns in the dark, without support, love, or critical inquiry. I had to discover the language in which to explore loss. I found resolution in philosopher and theorist Judith Butler’s writing: “Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something. This seems so clearly the case with grief, but it can be so only because it was already the case with desire. One does not always stay intact. One may want to, or manage to for a while, but despite one’s best efforts, one is undone, in the face of the other, by the touch, by the scent, by the feel, by the prospect of the touch, by the memory of the feel.”1

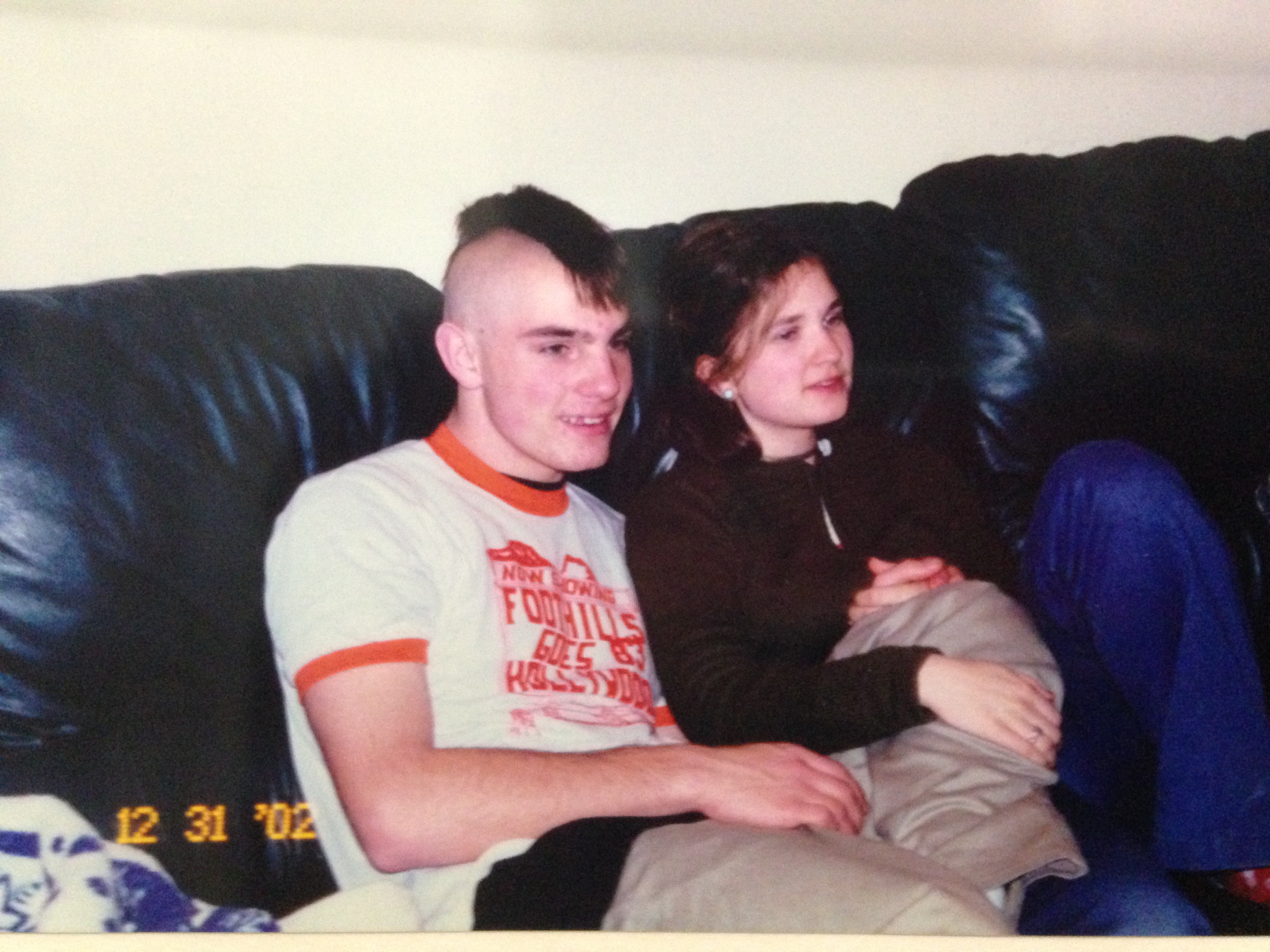

Matt was my first love in the storytelling way depicted in teen genre movies, cliché for cliché. As an angry, depressed, and outspoken young lady, I had met my match. Matt was hilarious, too, and a troublemaker. And he was wickedly smart. I understood his antics as a familiar and comforting way to respond to the experiential absurdities inherent with coming of age: he pushed against the world in ways that made sense to me. My memories of him are still so vivid, as spending that part of my life with him by my side was the first time I truly felt comfortable. I had the space and capacity to live those moments fully—without worry for my safety, the trustworthiness of others. I now had someone to lean on.

Matt was my first love in the storytelling way depicted in teen genre movies, cliché for cliché. As an angry, depressed, and outspoken young lady, I had met my match. Matt was hilarious, too, and a troublemaker. And he was wickedly smart. I understood his antics as a familiar and comforting way to respond to the experiential absurdities inherent with coming of age: he pushed against the world in ways that made sense to me. My memories of him are still so vivid, as spending that part of my life with him by my side was the first time I truly felt comfortable. I had the space and capacity to live those moments fully—without worry for my safety, the trustworthiness of others. I now had someone to lean on.

Just before college, but after a series of high school break-ups and reconciliations, we found ourselves seated across from each other in a booth at Dennyʼs. We swore a pact to reconvene the relationship after we had graduated. I noticed the waitress pitying Matt’s freshly shaved head as he ordered Moons Over My Hammy; she incorrectly believed that he had cancer. Our meal was free.

When I received the phone call that Matt had been in an accident, I remained calm. I quickly responded by asking if he was okay, assuming that he was untouchable. Matt had been my rock, there was no way he wouldn’t bounce back from whatever had happened. Steve, a mutual friend, was silent, and started to cry. “Matt,” he stammered, “he didnʼt make it. He’s gone.” I collapsed to the waxed floor in the Wegmans juice box aisle. My body was no longer my own, and it would not breathe. Customers stepped aside and then left the aisle with the messy teenager sobbing on the ground. I lay there at the feet of the boy I was seeing at the time.

Matt had an open casket. I was startled by this. He had been riding his bike when he was abruptly struck, and died shortly thereafter. Kneeling at his casket, I looked at his face. His eyes were closed, his face unshaven. His hair was longer than I remembered it. Despite this, his face and hands showed no sign of trauma. His exterior did not accurately display his death; his body was a facade. Leaning forward slowly, I reached out to rest my hand on his. He was cold. Unsure of what to do, I quickly kissed him and hoped that no one had seen it. I had never expected to see a dead body at my age: I didn’t read about it in books, or view it on TV. My family had never discussed death with me. Nobody had taught me what to do in this moment. How would I hold on to it, fighting against the impermanence of memory? I needed this view of him to stay with me forever. As a photographer, I wished I had brought a camera. I still wish that I had.

While my friends got ready for college, I dreaded moving across the country to go to college in a place where I knew no one. I was terrified of trying to make friends who would have no idea what I was going through. And so I spent most of my first college semester in bed, struggling to maintain my daily life, while tallying how many days Matt had been dead. My hometown friends were off to other universities, making new friends and enjoying the transition; but I was floundering. I was unable to push my mourning process aside, which did not mix well with the burgeoning freshmen social scene developing around me.

I’m still learning how to adjust to Matt’s death. Mourning does not end. Eventually, I learned to adjust to the emptiness, to coexist with the continual struggle. Growing up without constants, I had relied on Matt’s comforting presence in my life. I have long since regained my footing, but his absence is felt daily. I can’t forget him or pretend I am no longer affected. This past June, for the tenth time, I observed the anniversary of his death; it may have been the hardest. Mourning is not a linear process, but rather deviates from its prescribed social path. Mourning is both stagnant and pervasive, weaving throughout the mandatory “first year” of grieving and trickling into all moments beyond. I found myself unexpectedly hit with a wave of despair after all of this time, sitting on the side of the road where he had been hit, ten years prior. The notion that time heals all losses is not true.

I’m still learning how to adjust to Matt’s death. Mourning does not end. Eventually, I learned to adjust to the emptiness, to coexist with the continual struggle. Growing up without constants, I had relied on Matt’s comforting presence in my life. I have long since regained my footing, but his absence is felt daily. I can’t forget him or pretend I am no longer affected. This past June, for the tenth time, I observed the anniversary of his death; it may have been the hardest. Mourning is not a linear process, but rather deviates from its prescribed social path. Mourning is both stagnant and pervasive, weaving throughout the mandatory “first year” of grieving and trickling into all moments beyond. I found myself unexpectedly hit with a wave of despair after all of this time, sitting on the side of the road where he had been hit, ten years prior. The notion that time heals all losses is not true.

So much of my work brings death and its messiness into the public arena, with the aim of reducing the topic’s shock. Acknowledgment of death provides the space for exchanging support with other survivors of loss. This doesn’t make it easier, but it helps make sense of it. As a young adult, grieving was wholly isolating; I lost friendships with those who didn’t know what to say to me (my dad refuses to talk about it even still).

This heaviness did not abandon me, but my body adjusted to its weight as I stepped forward, perhaps a little stronger and more deliberately. I’ve found ways to take on this difficult burden through photographic and literary endeavors, with the belief that by sharing my work with others my work with death to would be beneficial. I want people to learn, less painfully than I did, that things often get better with time, but they do not heal like scars, they do not fade into nothing. It is better that they do not.

1 Butler, Judith. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004. 19.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.