Dilettante Army Salon: The Society of Dilettanti

Here at Dilettante Army, we’re interested in all kinds of important questions about artists’ groups and social knowledge:

- How do artistic communities form?

- What conditions are necessary for them to flourish?

- How are they funded?

- How do they function?

- How do we get invited to be a part of one? We’ll bring snacks!

When Google searches came up empty, we decided that we should probably ask around to get other people’s opinions. Thus, the Dilettante Army salon dinner was born. (We were serious about the snacks.)

Over the past several months, we’ve started a series of salon dinners that are themed after historical periods in which an artistic community flourished. Prior to each dinner, we send out a list of required readings, and guests read the texts and come to dinner prepared to engage in discussion. D.A. prepares a meal (roughly) in the style of the time period being discussed, and then we eat and try to figure things out.

For our inaugural salon dinner, we chose to study the founding period of our namesake group, the Society of Dilettanti. Each dinner guest was asked to analyze the world of 1730s aristocratic London by using the following texts:

- The Society of Dilettanti: Archeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment by Jason M. Kelly

- British Clubs and Societies 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World by Peter Clark

- “Le 1%, C’est Moi” by Andrea Fraser

These texts were chosen to provide ample historical information about how the Society of Dilettanti functioned and to spur discussion about how our current art/associational world compares with that of 1730s aristocratic London. But before you start anything at a Dilettante Army function, you have a glass of champagne!

Until the late 17th century, only still wine came from Champagne. But the English market loved the slight effervescence of some Champagne wines, and English industry developed stronger bottles (with coal-fired glass and a punt in the bottom) and cork stoppers that could withstand the pressures of carbonation and the rigors of a sea voyage. Sparkling Champagne slowly grew in popularity over the 18th century, but it’s a sure bet that the Dilettanti were rich and adventurous enough to drink it early on. (Image of 18th century wine bottle via The Society for Historical Archeology)

For dinner, we used the period-standard service à la française method instead of service à la russe, which was gaining popularity at the time but not likely to be used at the (relatively informal) Dilettanti tavern meals. The menus of England at the time were dominated by roasted meats and pies, with some vegetables and cheeses. There would be several varieties of meats, all heaped on platters in the center of the table. A dinner guest would serve him or herself from the platters in reach; there was no passing of dishes.

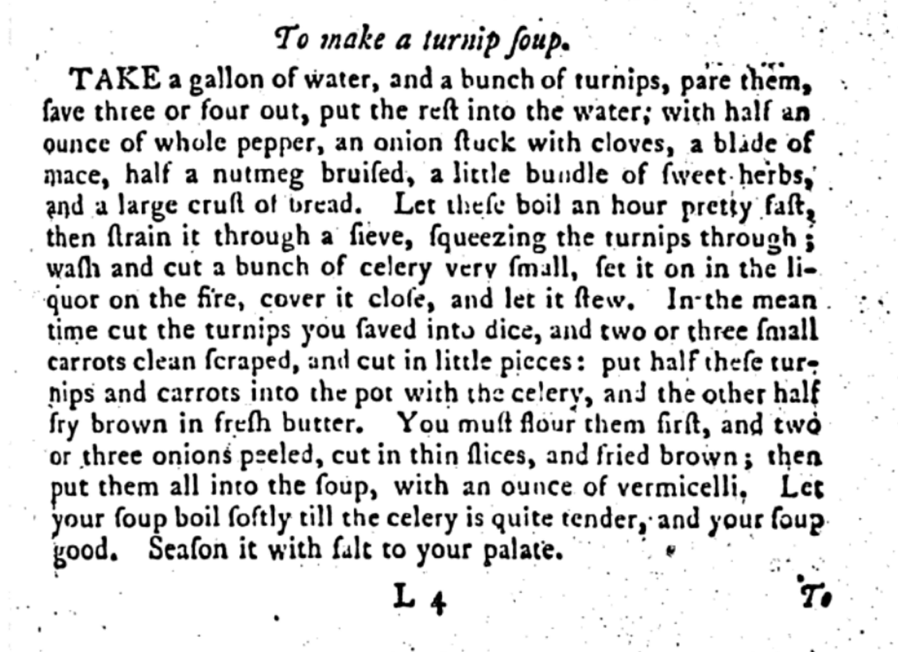

For the soup course we made turnip soup from a Hannah Glasse recipe. It was both delicious and strangely spiced. In between bites we chatted about the rise of the Society of Dilettanti.

In 1747, Hannah Glasse published the first runaway cookbook success ever, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, which was intended to help bourgeois ladies instruct their kitchen staffs. In the 18th century, spices such as cloves, mace, and nutmeg were used more widely in savory dishes than they are today. (Image via Google Books)

The Society of Dilettanti was an amateur association and drinking club for collectors of art and antiquities. It was founded in 1732 by a bunch of men who had been on the Grand Tour (a sort of study abroad, undertaken by young men of means to finish their education and acculturate them). These men were interested in maintaining the fraternal bonds they had formed on the Continent and continuing the way of living they had enjoyed there: opera, wine, fine art, and rarities.

The early 18th century was a golden era for the associational world. Clubs and societies of all kinds sprung up in England, France, Germany, and the rest of Europe. Several factors spurred their growth, including increased urbanization, vast trading networks and associated migration, liberal governments, and a burgeoning press.

Rapid urbanization determined the public nature of society meetings. London experienced a long and robust construction boom, including many fashionable squares with townhouses built up around them (mostly on spec). Those homes were large in terms of modern day city apartments, but they were small compared to country estates, meaning that large house parties were unfeasible except for the very wealthiest mansion-dwellers. Home life, therefore, was strictly domestic; socializing was done outside the home in taverns and inns, which were also rapidly built.

Clubs helped determine who exactly the right people were. In a time of movement and social flux, class barriers grew ever more fluid. Instead of bows and salutes, the egalitarian handshake came into fashion. The specificities of dress also became circumspect because of a large ready-to-wear fashion industry that was newly supplying the shops of London with clothes and hats. Absent visual and gestural status markers, refinements of speech and taste were one sure way to tell good breeding. Gentlemen cultivated “polite learning,” a middling path of erudition that was never so erudite as to be pedantic and never so ignorant as to be boorish.[i] This type of knowledge, which might have its closest modern kin in cocktail party conversation, was aimed at sociability and connection.

For the roast, we chose this buttermilk-brined chicken recipe with an accompanying cress and bread salad. Buttermilk and watercress were typical ingredients in the bourgeois cuisine of tavern cooking: lemons would have been a luxury. An English cook would probably have not used so much garlic, however: garlic was associated more with medicine and with the stinky French than with honest cookery.

The Society of Dilettanti exemplified polite learning. Their motto is “Grecian Taste and Roman Spirit,” which held a variety of meanings for them and for their peers. In its most plain sense, the motto points to Italian society, considered the most highly cultured in Europe, and to the Dilettanti’s experience of Italy during the Grand Tour. The Dilettanti were also claiming affiliation with the great cultures of ancient Rome and Greece, cultures that were becoming rapidly more evident as archeological practice (still in its infancy) tackled the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The spectacular art found in those places, with their depictions of pagan religion, open sexuality, and wealth, displayed an aristocratic lifestyle that the current leaders of empire were anxious to claim as heritage. That aristocratic lineage, importantly, included the libertinism of powerful empire as well as the solid statesmanship of republicanism. The Dilettanti embraced both values: they made culture and public taste and they claimed the privilege to act outside that taste when they saw fit.

Mushroom and leek pie stood in for all the other meat that we would have had if we were stressed about historical accuracy. But no man can eat 50 lark’s tongues and we did not try.

As such, a Dilettanti meeting was often more drunken party than serious artistic or academic undertaking, a mode that was entirely in keeping with the ethics of the time. As the world changed around them, however, the Dilettanti suffered a change in public opinion. Freedom of the press, such an integral part of the liberal exchange of ideas, also enabled the wide circulation of reports on Dilettanti behavior, which in a few notable cases became full-blown scandals. Their building and publishing schemes were plagued by delays and failures. Eventually, the Dilettanti decided that instead of focusing on their own projects they would help fund and supply larger endeavors, endeavors which became institutions such as the British Museum and the British Library. Those institutions hired real professionals, not collectors or enthusiasts, and by the 19th century Britain had largely moved on both from the Dilettanti and the Neoclassical movement they helped fuel.

To accompany the roast course, we chose both a red and a white Bordeaux wine. Bordeaux exported a great deal of wine to England; the Gironde and Loire rivers provided an excellent shipping route, and Bordeaux had enjoyed robust trade relations with England ever since Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry II of England in 1152. The English court was enormously fond of Bordeaux wines, which they called claret. Although the wine that the term “claret” refers to has changed over the centuries, Bordeaux claret remains associated with the British upper class. (18th century map of Bordeaux via French Moments)

As we finished the roast course, the discussion shifted from the origins of the Society of Dilettanti to the club’s decline and impact on other social institutions. The eighteenth century saw the founding of a whole host of institutions—universities, museums, libraries—that developed professional standards for emerging disciplines like archeology and art history. As more individuals supported common institutions by donating or selling their private collections to museums, knowledge and access became more centralized. Some of those institutions, like the British Museum, have become monolithic in stature. With defined and divided disciplines, the academic structure to support specialization has made deep research and refined expertise normative. However, the easy cross-disciplinarity of early groups like the Dilettanti has been somewhat less maintained. The art world requires agility and experimentation as much as it requires organization and discipline. Smaller organizations, lacking in gravitas but with fewer strictures, provide that.

In the Traité historique et pratique de la cuisine, published in 1758, the anonymous author praises uncomplicated dishes of the nouvelle cuisine trend like haricots verts dressed with a vinaigrette. The author also points out that you can make designs with the beans on a platter, because there’s no need to be as simple as all that. Here, green beans are the unlikely flash point between ancien régime elaboration and Enlightenment simplicity. [ii]

Two thirds of our readings for this salon sent us back in time to the eighteenth century. In order to bring the discussion back into present day, we also included Andrea Fraser’s essay “Le 1%, C’est Moi” (included in the 2012 Whitney Biennial catalog). Fraser is an internationally acclaimed artist who shows at big institutions with rigid gatekeepers and has made a career-long critique of those same institutions. In “Le 1%, C’est Moi,” Fraser tracks some of the complicities and absurdities that complicate the work of art. She cites an Art Market report which found that 50% of the money in art funding goes to 5% of artists. Added to that, the number of buyers at top-level auctions is incredibly small—maybe 500 people support the top tier of art patronage. What we have, then, is an insider’s game in the top 1% of capitalist enterprise that is matched by a teeming, striving underclass of artistic producers. Fraser acknowledges her place within this system even as she points out its failings. Current criticisms of international art are too many to count, but here is a brief list.

- The art world is obsessed with money.

- The art world is more concerned with popularity than with quality.

- Art stars are overexposed.

- The majority of working artists are underexposed.

- International art fairs are crass events that determine market value.

- The high art market is cravenly manipulated by galleries.

- Artists are undercompensated for their labor.

- Government support for the arts is the United States is nonexistent.

- The price of an art education is absurdly high.

- The artist’s onerous duty in a glutted economy is to brand-building and self-promotion.

Presenting this list at Dilettante Army headquarters gets you what you would get most places: a few counterexamples and no real answers. But we are fond of counterexamples, and we would like to expand that list over cheese.

The last course in an English meal incorporated sweet pastry and cheeses. Soft cheese was not imported in quantity from France or anywhere else due to its perishability, but solid English cheeses like Wensleydale, Cheddar, and Stilton were quite popular.

The Dilettanti world suffered from many of these issues: it was elite and it was privately funded by the wealthy. But these badly behaved aristocrats contributed to a shift from private to public, if not in funding then in access. They tried mightily to found their own institution over many years. They had sets of architectural plans, they bought a lot and dug out a foundation, they even bought some stone once—but they never quite got it together. Most of the Dilettanti eventually threw in their lot with the people working on founding the British Museum. The peerage and the royals came together on that monumental project, solidifying knowledge in one common place. Dilettanti members donated statues, paintings, gems, vases, and books. They got King George III on board, and he gave his entire library to the museum (he wasn’t much for reading, anyway). Art history and archeology were ensconced as disciplines through that institution, thoroughly professionalized.

The most important part of the third course are the beverages: brandy, port, and coffee. All three were well established as social drinks in England from the early 17th century. Brandy came from the Loire valley, where the Dutch had organized large scale brandy production beginning in the 1620s. Port came from Portugal, a sea power with vast shipping networks. And coffee came from French and English colonial assets, heavily sweetened with sugar from the same sources.

There’s a lot of anxiety these days around professionalization and the arts. Curator Daniel S. Palmer’s essay “Go Pro: The Hyper-professionalization of the Emerging Artist,” for instance, has been shared 20,000 times on Facebook. In it, Palmer relates the story of an appalling studio visit with a young painter (to whom Palmer gives the gift of anonymity). During the painter’s practiced speech, his accompanying gallery representative offers key pieces of information and then abruptly closes the visit with a direct appeal to include the painter in one of Palmer’s upcoming shows. It’s a stilted and highly mediated encounter, more corporate pitch than collegial discussion.

This outlandish scenario is meant to typify the newly (not so newly) corporate art world, in which artists are simply producers that supply an international luxury market. Every art worker feels like they know a person like that painter: young, ambitious, probably white and male. Everyone is equally sure that they themselves are nothing like that, which is why so many people have shared that article, because then we can all point to that person and collectively shake our heads. The general malaise of an art world in which large institutions and their gatekeepers seem to control all of our fates makes this an easy and very satisfying example. It doesn’t require any action of the reader beyond consciousness raising. But we should see our own complicity in this scenario, in which a very particular kind of artist is looking for the backing of a very particular kind of institution. Small artist-run groups provide an alternative here; it is not always wise to throw in our lot on one huge project, eliding difference for the sake of consolidating power. The early years of the Dilettanti have been instructive, and their food was pretty good too.

[i] Jason M. Kelly, The Society of Dilettanti: Archeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 21.

[ii] Susan Pinkard, A Revolution in Taste: The Rise of French Cuisine, 1650-1800 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 181.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.