It’s Not Right But It’s Okay: Looking at Postmortem Photographs (of Whitney Houston)

In the 21st century, it’s safe to say that we have a very limited interaction with the dead. This is a recent development. If we can take a moment to reflect on the history of humanity, we will recognize that our current relationship with death is more distant than ever. We are not expected to cleanse the remains of our loved ones, nor will we ever feel the anxiety of seeing their flesh stiffen and leak before they go in the ground. Our modern relationship with death is sterile; it is sanitary but also lacking in the messiness that would indicate any kind of grief or closure. Contemporary mourning is a short and private period after which we are expected to return to our lives in a way that does not burden those around us. It is contained safely within the confines of our private spaces.

In the 21st century, it’s safe to say that we have a very limited interaction with the dead. This is a recent development. If we can take a moment to reflect on the history of humanity, we will recognize that our current relationship with death is more distant than ever. We are not expected to cleanse the remains of our loved ones, nor will we ever feel the anxiety of seeing their flesh stiffen and leak before they go in the ground. Our modern relationship with death is sterile; it is sanitary but also lacking in the messiness that would indicate any kind of grief or closure. Contemporary mourning is a short and private period after which we are expected to return to our lives in a way that does not burden those around us. It is contained safely within the confines of our private spaces.

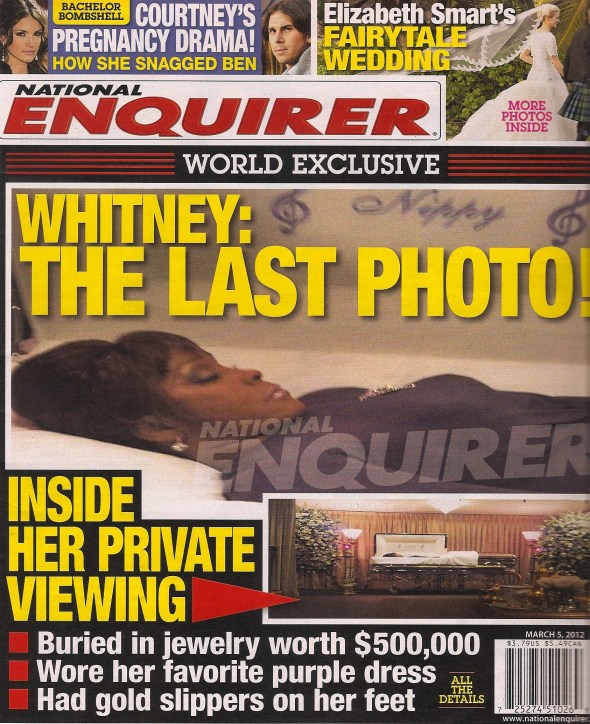

Despite our cultural inclination to deny death, death is unavoidable. As one of two natural events that happen to all living beings, it is only doing us a disservice to skirt the issue and continue to push it away until we’ve quarantined death into some kind of bizarre alternate universe. Let me explain. It’s early March in 2012, and I am seeking out the shortest line in my preferred grocery store. I am slowly moving down the lines, and I choose an aisle. I am placing my items on the conveyer belt, and I am casually perusing the offensive headlines of the publications in front of me. My eyes meet the National Enquirer and I see a pixelated Whitney Houston: “WHITNEY: THE LAST PHOTO. Inside her private viewing.” On the front cover, I see a low quality image, blown up too large. The edges are soft and the colors begin to distort. Just beneath her, there is a view of the casket in the context of the room. The anonymous photographer must have quickly taken these before or after the service, most likely with a cellphone.

As a person who is in support of exploring a healthy and open dialogue regarding death, mourning, and everything in between, I can’t say that Whitney Houston’s “last photo” on the cover of the National Enquirer is a great first step in this process. By sticking celebrity postmortems between salacious stories about alien abductions and sex scandals, the Enquirer creates a troublesome context in which the reality of death becomes as strange and superficial as the surrounding fictions. Shock value is rarely an ideal instigator for legitimate discourse.

Much of the response to Whitney’s “last photo” was largely about the morbidity of the person who took the photos hoping to make some money off of the dead and the mourning. The act of photographing the dead, however, is not without cultural context. From the inception of photography in 1839, the postmortem photograph has been a common practice in mourning. There is a lot of wonderful scholarship on this bit of history, [1] but needless to say: postmortem photography was both popular and practical for a variety of technical, social, and cultural reasons. Postmortem photography fell out of popularity as photographic technology advanced, people began to live longer, and people began to photograph life instead of death.

The desire to photograph the dead is not new, especially when considering the death of celebrities or public figures. Martin Luther King Jr. was photographed in casket by reputable photographers, such as Cornell Capa, for Magnum, an extremely prestigious photographic cooperative. High quality black-and-white photos taken by the Associated Press were later printed in Time magazine and offered a glimpse of the fallen Civil Rights leader, nestled in his casket but shielded from the living behind a pane of glass. These images are sobering, but they also exhibit a sense of decorum that ought to be prioritized in sensitive situations. Despite the political significance that King has, I hope to point out that a showing a photograph of a deceased public figure does not have to be without respect, nor does it have to be offensive.

With this stark contrast between the respective photographs of King and Houston, it is clear that it is not the actual existence of postmortem photographs that is problematic, but the issue is rather the blatant lack of dignity in the Enquirer’s cover with Whitney Houston. Those shocking photographs of Houston in her coffin, pixelated and seemingly taken in a surreptitious manner, were treated as objects of trade and profit. The Enquirer published a photograph that was unauthorized by the family, which was a clear invasion of their privacy as well as a final invasion of Houston’s. As a woman who was constantly forced to be in the eye of the public, this final gesture of disrespect is especially traumatic.

With this stark contrast between the respective photographs of King and Houston, it is clear that it is not the actual existence of postmortem photographs that is problematic, but the issue is rather the blatant lack of dignity in the Enquirer’s cover with Whitney Houston. Those shocking photographs of Houston in her coffin, pixelated and seemingly taken in a surreptitious manner, were treated as objects of trade and profit. The Enquirer published a photograph that was unauthorized by the family, which was a clear invasion of their privacy as well as a final invasion of Houston’s. As a woman who was constantly forced to be in the eye of the public, this final gesture of disrespect is especially traumatic.

The audience of the publication is crucial when considering how these images were published. When Time magazine printed this photograph of Martin Luther King, it was part of a two-part piece on his assassination. Printed eight days after his murder on April 4, 1968, the weekly publication penned “An Hour of Need” and “The Assassination” in response to the murder of the Civil Rights leader. The article provides a broader context for the viewer of the photograph. The cover of the Enquirer, however, does not provide any kind of sobering journalism for Whitney Houston, just eye-catching statements. Time also gives the viewer a chance to come across the article on an inside page and view the photograph within its context. Without the same opportunity, the viewer of the Whitey Houston cover is automatically caught off guard. There is no invitation to consider the photograph; there is only a startling, visual surprise.

The focus of the photograph in the Enquirer is also incredibly different from the photograph published of Martin Luther King in Time. The large image of Whitney Houston is zoomed in and cropped tightly so that she is removed from any kind of spatial context. This photo was taken covertly, seemingly without thought to its publication format, and it does not give any of the spatial context required to make visual sense of the space. The zoomed-out photograph that sits to the bottom right shows the funeral parlor. The interior space is empty: there are no chairs, no flowers, no signs of human life. There are no viewers of the body. It shows the moments before or after the viewing hours, where someone may have snuck in, not to show their respect, but to gawk inappropriately.

The Time photograph shows Martin Luther King surrounded by viewers. King is surrounded by solemn onlookers, including the stares of unsure children. In this space, it was appropriate to bring all members of the community. There are a variety of floral arrangements and wreaths behind the viewers, serving as another visual cue to the presence of life within this image. In the photograph of Whitney Houston, her stark surroundings show us nothing. Slapped on the front of the Enquirer, this isolated and deserted death is terrifying. The busyness of the King image, however, is proof that death can bring a sense of togetherness and of community.

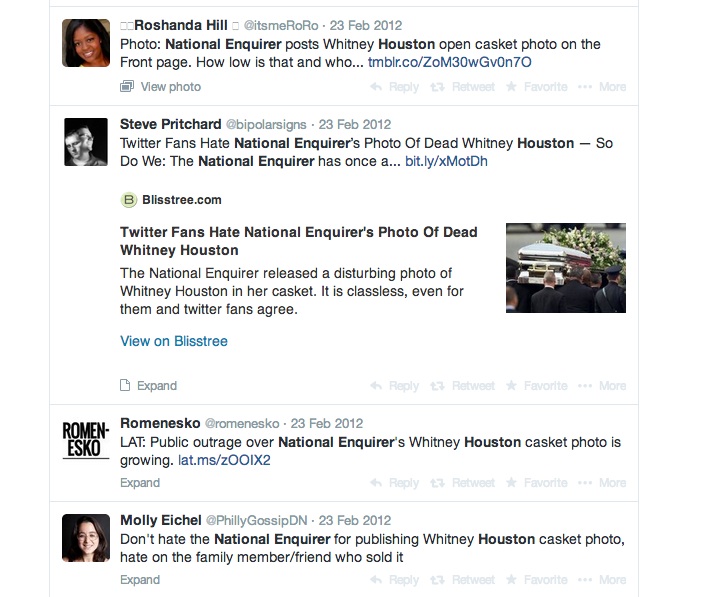

The Enquirer, with high hopes to finally turn a profit for their floundering publication, was interested in presenting a shocking cover story to the unsuspecting eyes of grocery store check-out lanes. Although there is no evidence that this particular edition turned an especially high profit, it did get people talking. People took to the internet to express their distaste, exclaiming that that the Enquirer had finally gone too far. People tweeted “SMH” (shaking my head), both to the Enquirer and to the seller of the photograph, in a response spread across Twitter for days after the release of the image. The Enquirer reminded us that death was messy, hard, and unbearable to view.

Death does not have to be what the Enquirer showed us. Death will be messy and hard, but it can be made more digestible if we are able to find ways to accept it into our lives. As we navigate towards our end, as we all ultimately do, I advocate for creating spaces and dialogues for death to be a tangible conversation, a discourse that can be approached over dinner or out with friends. I can’t imagine that any viewer of Whitney’s “last photograph” was inspired to have a productive end-of-life conversation with a loved one or an open dialogue about what happens after we die. Perhaps, if we are able to find ways in which death can become part of our larger context, it won’t create such a terrible gut reaction when we are forced to encounter it.

Death does not have to be what the Enquirer showed us. Death will be messy and hard, but it can be made more digestible if we are able to find ways to accept it into our lives. As we navigate towards our end, as we all ultimately do, I advocate for creating spaces and dialogues for death to be a tangible conversation, a discourse that can be approached over dinner or out with friends. I can’t imagine that any viewer of Whitney’s “last photograph” was inspired to have a productive end-of-life conversation with a loved one or an open dialogue about what happens after we die. Perhaps, if we are able to find ways in which death can become part of our larger context, it won’t create such a terrible gut reaction when we are forced to encounter it.

[1] For more information on postmortem photography, please see articles at PBS, Hyperallergic, and this article by Mark Dery.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.