Race to the Periphery

“It is my hope that my images provide some small contribution to my people—La Raza.”[1]

The Olympics may be a peculiar zone to seek out Chicana/o experience. Growing up in the Southwest I was not aware of any Mexican-American participants, which is not to say they did not exist. In 2002, Derek Parra surprised the world when he took a gold medal in the rather Nordic sport of speed skating. And although I learned of the victory twelve years after the fact, I was equally surprised. Indeed, a broad inspection of US Olympic competitors reveals Mexican-origin champions in softball, wrestling, weightlifting, water polo, and boxing. Nevertheless, it is fair to say involvement has been limited and relatively recent, with most medals coming after the 1984 Games. And while the rare Chicana/o Olympian momentarily situated at the center of athletic pageantry is important, this text is about peripheries. More specifically, it is about the expression of a Chicana/o perspective in relation to the Olympic spectacle, something photographer Louis Carlos Bernal struggled to demonstrate at the twenty-third, Los Angeles-held Games. What class of politics are the Olympics? Or better put, what class of politics by other means? While the Games were designed to bring various nations together in peaceful athletic competition, such utopic urges do not require the world itself to be at peace, only that the Games presume neutrality, that they be free of national and international policy, civic engagement, and social protest—in short, that they be apolitical. However, as any passing history of the modern Games affirms, international and domestic frictions are not easily bracketed from such symbolic and wide-reaching displays.[2] By the time Los Angeles was host in 1984, Cold War tensions had culminated in a series of punitive back-to-back US-Soviet boycotts. Moreover, the 1980 and 1984 abstentions swept up variously affiliated nations on both sides, echoing general political-cultural and ideological discord between the superpowers and their allies. And while the Cold War boycotts overtly recast the Games as an extension of foreign policy, idealized notions of Olympic neutrality and inclusivity continued to circulate. “The Olympics don’t belong to world governments. They belong to the world’s athletes.”[3] William E. Simon’s words, appearing in the New York Times, carried special authority. As president of the US Olympic Committee he helped inform the public’s understanding of the ongoing battle between the Games as idealized global convergence and political tool. But more importantly, he argued against the treatment of athletes and teams as extensions of national identity and for the reduction of government involvement in the Games. Certainly the celebration of individual autonomy and the reduction of government management, in all thing but war, were not out-of-place thoughts in Reagan’s neoconservative world order. Many such articles appeared in the weeks leading up to the Games, each one lamenting the role global interference played in the diminishment of Olympic autonomy. Various suggestions were made, including establishing a permanent home for the Games at their site of origin, Greece. However, in the end, the abstract and utopic notion of depoliticized individual competition was no match for the simultaneously petty and high-stakes squabbling of two nuclear-capable powers or for the commanding political image an Olympic boycott conjured on the global stage.

Such were the Games when Louis Carlos Bernal and nine other photographers received special commissions from the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee and the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies. The resulting exhibition, Ten Photographers: Olympic Images, was held at the LA Museum of Contemporary Art from November 18, 1984 to January 6, 1985. And while the various participants were given unique access to the spaces where the Games took place, the project was by no means a study in behind-the-scenes documentation. To the contrary, the artist-photographers were encouraged to follow their personal visions and interests, as opposed to expressing point by point the conventions of Olympic theater (the reproduction of national patriotism, the deification of athletic prowess, the capturing of victory’s thrill and defeat’s agony). Undoubtedly, more photographs of the hyper-mediated event were not needed, unless they be of a different class altogether. And while Ten Photographers showcased pictures explicitly made to reconfigure the Games as more than mere sport, it is hard to imagine the LA Olympic committee was totally pleased. In many ways the resulting photographs express a moment of grave reflection, a kind of image hangover experienced after the dizzying height of Olympic zeal was well slumped. This fact is made especially vibrant by Peter Schjeldahl’s somewhat incendiary catalog essay—a text bleakly titled “Anti-Olympic.” In it he takes the unrelenting presence of corporate sponsorship to task, calling the Games a “mass consumption of feelings,” and “no less delectable for being artificially flavored and packaged: McAffects (to borrow the advertising patois of one of the major sponsors of these Olympics).”[4] Indeed, McDonald’s funded a new swim stadium for the occasion; and major corporate support, along with 200 million dollars in television rights, ensured the financial success of the LA Games. But, as Schjeldahl points out, something about the photography project seems to “short-circuit” the mass consumerism of the Olympic program that sponsored its creation.[5] Essentially, these artist-photographers represented a critical response from inside the very spectatorial core, although with some exception and to different degrees.

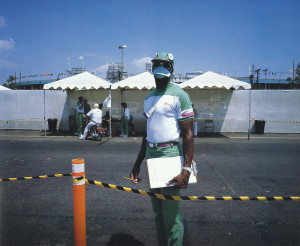

Despite the fact that Bernal does not get much attention in Schjeldahl’s essay, his photographs are particularly compelling, not only because he was a Chicano photographer and therefore a rarity, but because he ventured farthest and furthest from the center of official activity. Disturbed by the event’s elitism, “after a day or two he chose to photograph outside the Olympic park gates…[W]here multitudes of visitors and fans…created a joyous spontaneous street fiesta…”[6] There are, as Leslie Marmon Silko suggests in her account, examples of photographs taken in the surrounding ad hoc commercial areas where “boom boxes played norteño.”[7] Polaroid Vendor (1984) and Vendor, Blimp and Carl Lewis (1984) feature Figueroa Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard respectively—both flank Memorial Coliseum. But, it should be noted Bernal did not only photograph outside the official walls; he also made pictures in the many official and semi-official zones associated with mundane Olympic labor. Gate Attendant (1984), for example, focuses on a temporary employee encircled by spectators within a large stadium setting. Similarly, the nametags and uniforms in Sisters, Archery (1984) mark the two Chicana women as on-duty maintenance staff, more than likely near their areas of care.[8] Putting this aside, Silko is accurate in her general characterization of Bernal’s rejection. More than any other project photographer he ignored the spectacle of the Games most directly—the vast Olympic architecture, the strange technological apparatuses, the athletes (victorious or otherwise), and even the throngs of alternately bored and enthralled fans. What did he focus his camera on instead? And why?

Louis Carlos Bernal, Sisters, Archery, Long Beach, 1984. From 10 Photographers, Olympic Images (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies, 1984)

Louis Carlos Bernal, Bus Dispatcher, Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, 1984. From 10 Photographers, Olympic Images (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies, 1984)

Louis Carlos Bernal, Vendor, Blimp and Carl Lewis, Martin Luther King Boulevard, 1984. From 10 Photographers, Olympic Images (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies, 1984)

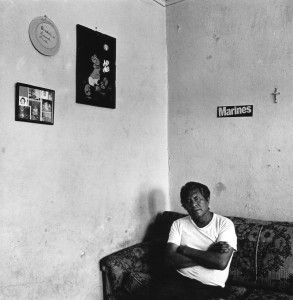

Bernal became known in the decade leading up to the Games, at least to certain attentive parties, as a photographer almost exclusively interested in documenting and constructing a particular politicized subjectivity. Photography was no disengaged assemblage of technologies and techniques, nor was it a philosophic matter of mechanical reproduction or picture making in the abstract. Photography had very personal stakes. “I wanted to convey what I found—the new sense of pride, the new awareness that is flowering both within myself and within the community.”[9] Here, Bernal is specifically referring to pictures made over a two-year trip through the US Southwest (1977-79).[10] Without doubt, most of his borderland pictures are easily incorporated into the 1960s and 1970s Chicana/o civil rights and labor struggles that were unfolding in the fields, cities, and schools where Mexican-origin US citizens found themselves most concentrated and dispossessed. Like other cultural producers associated with “the new sense of pride,” “the new attitude” of Chicanisma/o, Bernal created a specific visual grammar that both constituted and reflected an emerging, yet fragile, Chicana/o identity.[11] Situated where living takes place most intimately and humbly, Bernal’s archive of quotidian aesthetics and cultural signs pays tribute to bedrooms, living areas, dressing tables, kitchens, and other familiar domestic sites; it pays tribute to the self-possession of the body and gaze, to the transformation of ordinary space according to Chicana/o desire. In his images of brown life in US borderlands I recognize my own everyday environments, and understand these pictures as the catalog of a world unlikely to be recorded by anyone but a self-identifying Chicana/o.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Rancho San Pedro, Animas, New Mexico, 1978. From Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Pima Community College, 2002)

Louis Carlos Bernal, Juan Mejia, Douglas, Arizona, 1979. From Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Pima Community College, 2002)

Louis Carlos Bernal, Juanita Serrano with Santo Nino de Atocha, 1978. From Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Pima Community College, 2002)

Louis Carlos Bernal, Rancho San Pedro, Animas, New Mexico, 1978. From Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Pima Community College, 2002)

Beyond the politics of “what to make pictures of” is “how to make pictures.” Bernal’s practice—prior to, during, and after the Olympic project—manifests a specific nuanced concern for the process of doing photography, for negotiating and decentralizing the technology’s inherent structures of power. Chicana/o subjects and their various environments not only provided Bernal with an aesthetic opportunity, but an ethical one as well. Thus, gaining a sitter’s faith served an integral purpose, something beyond the sense of intimacy a photographer might try to instill in a portrait. Ann Simmons-Myers, curator of Barrios (Bernal’s 2003 retrospective), attests to this principled approach. “Lou thrived on the challenge of engaging people in order to gain their trust and make truthful images of their lives.”[12] In his own words Bernal confirms this claim, as well as his belief in photography’s extreme sociality, a sociality which exceeds the circulation and proliferation of images and even the phenomena and epiphenomena of making pictures. “I’d like to be able to come back,” he ruminates. “I want people to feel that if my photograph wasn’t flattering, at least it was fair.”[13] The desire to return is a powerful force in Chicana/o identity formation. It resonates with both the desire for a homeland (Aztlán) and the return to an inviolate Indigenous past, to a time when the Hemisphere was more or less free from colonial control. Such a recuperation is by no means literal, and thus requires creative revisions and reworkings of all kinds. Furthermore, the desire to return in good standing to the places and people pictured gives photography a new and unlikely ontological dimension, one dependent on ongoing and future social relations between the image maker and the depicted, between the one with the power to see, frame, and snap, and the one that is seen, framed, and snapped at. It is a dimension brought out of a basic lived fact. Bernal photographed a community to which he belonged and wished to continue to belong. The resulting pictures are rarified aesthetic objects clearly in dialog with contemporary photographic conversations at the time, but they are also constituted by the social network they connect and connect to, by the maintenance of an ongoing lateral affiliation to the various communities Bernal entered and made pictures in. Understanding the specter of the “truthful image” in this context means deciphering “truth” through what Bernal calls “fairness,” which in turn links the act of photography to an imagined future, to the fostering of a developing and ongoing relationship not finalized in the act of picturing. In this formulation, photographic fact is not contingent on detached, objective reportage, or photography’s status as evidentiary, straight, and unaffected—and especially not on its claims to stand-alone aesthetic thingness. Rather, a photograph’s relationship to truth is dependent on larger social systems and community structures, whether or not the photographer is welcome back, whether or not the photographer sustains a relationship of belonging and is a trusted member of the depicted community.

How does one apply a photographic aesthetic and ethics built on fairness, reverence, lateral networks, and community engagement to an Olympiad—a spectacle as mobile and vast as the global telecommunication systems by which it circulates, an event that venerates the super-rarified champion over the everydayness of maintenance, that strives to bracket out issues emerging from the social field? Describing and conceptualizing the LA Games as antithetical to the aesthetics and ethics of such an important Chicana/o artist is distressing, particularly given the overall character of South and Central Los Angeles as largely marked by ethnicity and race. Carol Van Brunt, PR Head of the LA Olympic Organizing Committee at the time, expressed concern regarding minorities and the LA Games. In particular, she wondered under what circumstances minoritarian Los Angelenos would benefit from the inevitable financial upticks the globally attended spectacle would encourage. Brunt’s concern, tellingly voiced in Jet magazine, is exceptionally pertinent as the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, where many of the most popular track and field events took place, was (and still is) “located in a heavily Black and Hispanic area.”[14] Let us uphold that Bernal embodies a specific Chicana/o aesthetic and approach to making pictures, even while not photographing Chicana/o figures and scenes. If this is true, how does such an assertion affect what counts as Chicana/o? Any reconciliation of this issues would mean interpreting Chicanisma/o more broadly, expanding the term beyond the constraints of specific geo-political, socio-historic parameters—although such realities should never be forgotten or swept away. Clearly, there was something akin to Chicana/o identity in the invisible and tedious labor required to give the Olympic games their effortlessness, in the various grounds personnel, gate watchers, temporary staff, and impromptu entrepreneurs of all complexions and creeds. The link between these anonymous and semi-anonymous workers and the cultural economic position of the Chicana/o are made visually overt in the formal correspondences Bernal envisions between the Olympic pictures and his overall body of work. In both instances, the sitter seems to guide the image, generally facing the camera as a participant in the making of the portrayal. Rare is the photograph taken by Bernal wherein the subject is unknowingly caught up in the camera’s gaze. In both instances, the surrounding environment is fundamental to meaning, as much the subject as the sitter. But perhaps more importantly, in both instances the establishment of poise and personhood are central themes. Olympic workers are shown in the assorted contexts of their employment, but they are also shown as irreducible to the status or utility of that work. They are never overdetermined by their involvement in the Games, by the Olympic uniforms, accessories and goods. Instead, these laborers-of-the-spectacle project a sense of self, and are rendered, if not flatteringly, then at least fairly.

[1] Louis Carlos Bernal, Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American (Oakland: Oakland Museum of Art, 1978).

[2] In 1968 two American athletes were expelled from the Mexico City Games for raising their clenched fists in what appeared to be Black Power salutes during their medal ceremony. It was an act that not only resulted in their expulsion, but also ruined each of the athletes’ careers. In 1972, the infamous Munich Games continued after eleven Israeli athletes and coaches were taken hostage and killed by the militant group Black September. The 1976 Games were protested by a consortium of African countries in protest of South Africa’s ongoing racism and genocidal apartheid policies. Although South Africa had been banned from the Olympics, New Zealand maintained a sporting relationship with the country, which meant sending athletes to South Africa to compete in games that only allowed whites. When Soviet troops entered Afghanistan in 1980, the US responded by boycotting the Games. Naturally the Soviet Union retaliated and refused to send athletes to the L.A.-held Games, citing the whipping up of “anti-Soviet hysteria.”

[3] William E. Simon, “Olympics for the Olympians,” New York Times (New York, Jul 29, 1984), E 23.

[4] Peter Schjeldahl, “Anti-Olympus,” 10 Photographers: Olympic Images (Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984), 9.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Leslie Marmon Silko, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Prima Community College, 2002), 31.

[7] Ibid.

[8] I say they are Chicana as a political ploy, despite having only the visible and physiognomic to go on in my identification.

[9] Louis Carlos Bernal, Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American (Oakland: Oakland Museum of Art, 1978).

[10] Between 1977 and 1979 Abigail Heyman, Neal Slavin, Louis Carlos Bernal, Morrie Camhi, and Roger Minick travelled the US Southwest making pictures of Mexican-American life. They were supported in their efforts by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) as well as by the National Endowment for the Arts. Envisioned as a commemoration of MALDEF’s ten-year anniversary, the project resulted in an exhibition—Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American—that toured Oakland, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

[11] Bernal, Louis Carlos. Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American (Oakland: Oakland Museum of Art, 1978).

[12] Ann Simmons-Myers, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Prima Community College, 2002), 7.

[13] Ibid., 8.

[14] Jet (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, April 9, 1984), 8.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.