Psychic Violence: the Hauntings of Sarah Winchester

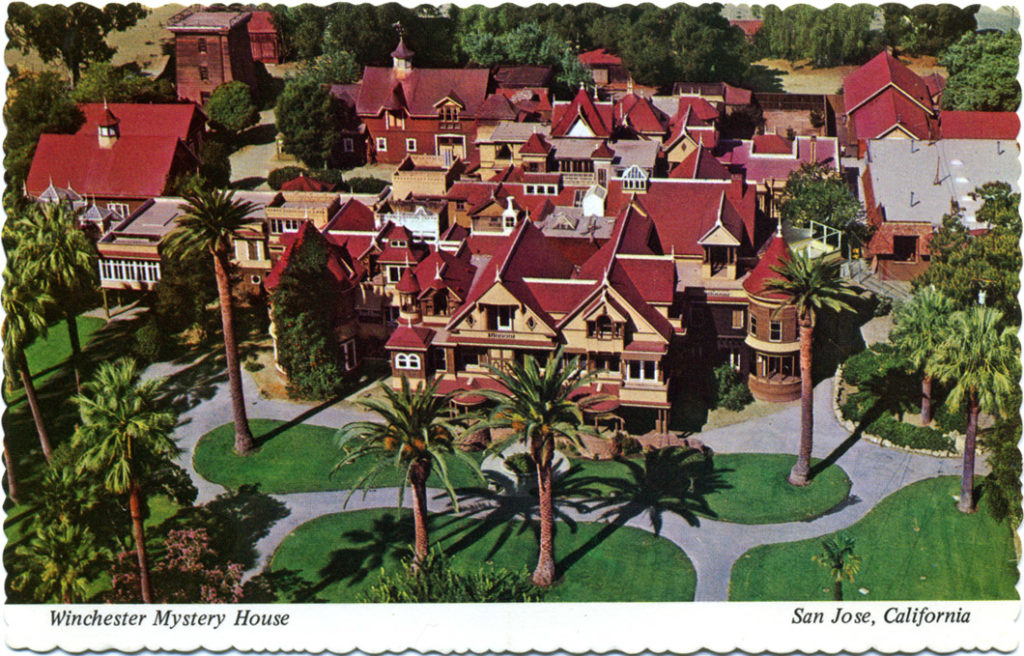

The stories that are sold to tell and re-tell American history are often simplified and boiled down to single-voice narratives that are sensational and disappointingly un-complex. Narratives are constructed to intrigue contemporary audiences but lack the multiplicity of voices and experiences that historical research and storytelling ought to provide. One telling example of this is the Winchester House in San Jose, California.

The Winchester Mystery house is a sprawling and bizarre complex in San Jose, California. Its original structure was a large but unfinished farmhouse, purchased by Sarah Winchester in 1884. By then, Winchester had buried her infant daughter as well as her husband and traveled West under the advisement of her doctor and/or spiritual guide, who told her that she should seek a new home. Carrying the burden of her losses, she sought to find a sense of fulfillment in her life by expanding her horizons.

Sarah Winchester portrait via Wikimedia Commons

Expansion, whether cultural, geographic, or architectural, was particularly poignant in the era of Westward Expansion, as essayist Rebecca Solnit writes: “A spiritualist medium told [Winchester] she would be safe as long as construction continued, and the house came to seem like the emigrant West itself in its insatiable desire for expansion.”[1] Spiritualism, a religion that was founded in New York in 1848, promised communication with the dead. The religion gained popularity and footing in the United States amongst those who sought to make contact with their deceased loved ones, who had increased substantially in numbers during the American Civil War. Winchester may have found comfort in the line of communication that Spiritualism offered. She may have also sought safety after losing both her husband and child; a guarantee of tolerable and equitable things to come, if she only continued to grow her home. By taking up and owning space, Winchester demonstrated her value and her fortune, and she secured the legacy she would leave after death.

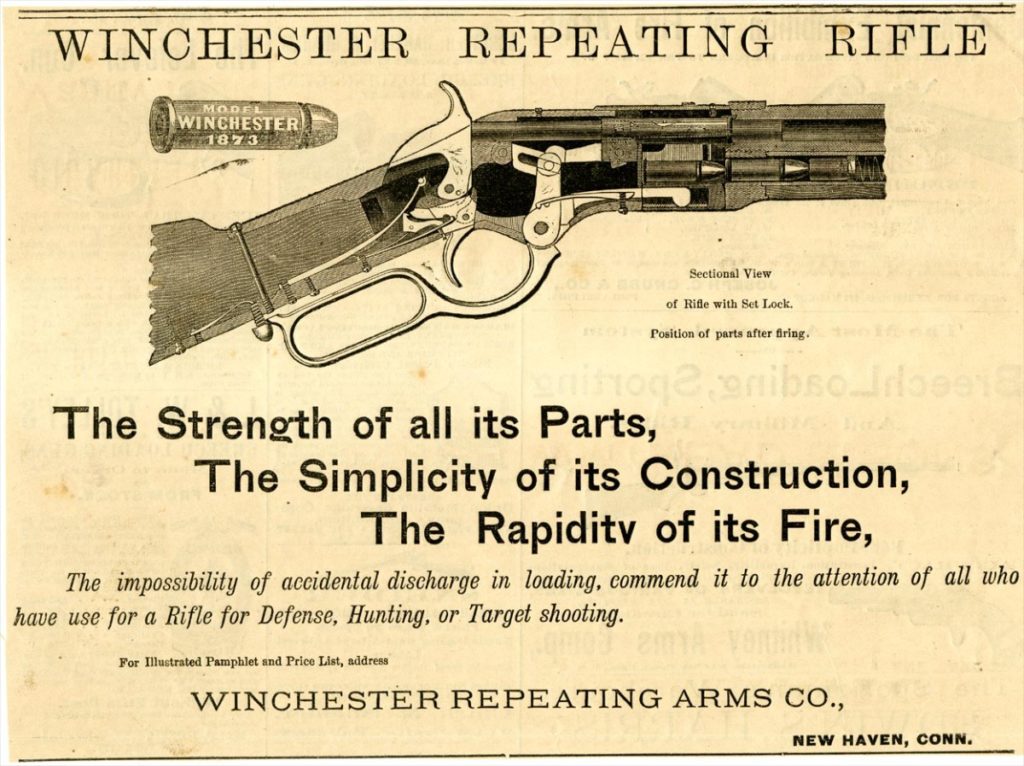

Sarah Winchester sought to ensure her own legacy by building a structure in the Winchester name that might negate the evils associated with it. She was wealthy from the fortune that the Winchester family had brought her husband: an immense profit from the development of the repeating firearm, including the 1873 model often described as “the gun that won the West.”[2] Despite the financial success that the Winchesters found from this, Sarah Winchester was left to navigate lingering guilt and anxiety surrounding the legacy of violence which the gun also gave her.

Advertisement via Winchester Repeating Arms

In 2017, the Winchester Mystery House is privately owned as a tourist destination, bed and breakfast, event space, and inspiration for an upcoming movie. The name “Winchester Mystery House” is trademarked; the story of Sarah Winchester’s Spiritualist practices and mansion-building anxiety is laid out on the home’s website. The official narrative, shaped and sold by the current owners of the Winchester House, is an ongoing tale that is re-told hesitantly by writers because there is little evidence suggesting why Sarah Winchester built her home in such a way.

This narrative suggests that Sarah Winchester used the architecture of the ever-growing home as a way to confuse the ghosts that sought to haunt her, namely those murdered by the gun that bore her own name. This sensational story has been picked up and repeated. Many of those slaughtered in the Westward Expansion were Indigenous Americans, whose populations were vastly decimated to make room for the various interests and desires of the newly inhabiting white colonists who continued to push toward the Pacific. It seems plausible that if Sarah Winchester were haunted by those murdered by the gun, Indigenous Americans would be at the top of that list.

The contemporary owners of the Winchester House tell the story of the nightly séances that Sarah Winchester held in her home, communicating with the spirits that threatened to haunt her.[3] She sought guidance on how to continue to shape and build her space to remain safe from their psychic warnings. Winchester used her funds to continually grow the house and build confusing rooms, passageways, hallways without ends, a majestic ballroom, and secret chambers. As if the spectral beings could be contained and confused by material walls, she pushed forward with the sprawling home.

Winchester House stairways via Painters of Louisville

The construction was ongoing and around the clock: the structure was constantly evolving and responding to the guidelines offered by Sarah Winchester and the many hauntings that may have followed her. After 38 years of continual construction, the house came to an abrupt stop when Sarah Winchester died at home, in her sleep, on September 5, 1922. The Winchester Mystery House’s website tallies the final extent of the house: “At the time of her death, the unrelenting construction had rambled over six acres. The sprawling mansion contained 160 rooms, 2,000 doors, 10,000 windows, 47 stairways, 47 fireplaces, 13 bathrooms, and 6 kitchens. Carpenters even left nails half driven when they learned of Mrs. Winchester’s death.”[4] With her death there must have been a sigh of relief: her obvious concerns about her family’s violent legacy had been laid to rest. The workers that had worked diligently on the home were freshly unemployed, and the house, finally, was finished.

The Winchester Mystery House™ sells one chosen narrative of the house; not only is the story sold, but so is the experience of the home as a tourist destination and commercial entity. While the home is ripe for more nuanced interpretation, it’s evident that visitors are only given one piece of the puzzle, one that sells a particular story and financially benefits from a single narrative about a rich, white woman, plagued with anxiety of her family’s violent invention and her downward spiral into architectural madness.

The Winchester House business elides any competing narratives and minimizes historical context. This approach to storytelling continues to erase the story of the Indigenous ghosts that haunted Sarah Winchester and simplifies a history of violence into one woman’s experience with ghosts. Edward Said, the postcolonial theorist of Orientalism fame, writes:

The nations are narrations. The power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism, and constitutes one of the main connections between them. Most important, the grand narratives of emancipation and enlightenment mobilized people in the colonial world to rise up and throw off imperial subjections; in the process, many Europeans and Americans were also stirred by these stories and their protagonists and they too fought for new narratives of equality and human community. [5]

The ongoing framing of the Winchester House as the product of colonialist anxiety blocks the narrative of mass violence and spiritual trauma waged against those who fell to the Winchester gun by highlighting the experience of the colonialist. This story, with its approach to white guilt plagued with ghosts and money, is arguably easier to digest and sensationalize than the mass extinction of indigenous cultures. This kind of erasure is both sharp and to the point, while also maintaining an ongoing violence through re-telling. The trauma is continually re-opened and re-exposed due to historical erasure.

The Winchester House is only one tiny piece of an American narrative that seeks to highlight colonized experiences over those that have been colonized. This is not new nor radical in a world where this violence is continually re-enacted. While the history of Sarah Winchester is worth noting and telling, it is vital that we make room for and elevate the stories and experiences of those that have been erased. For every Sarah Winchester story, there are so many more possible narratives to tell about those whose lives were cut short: thousands of voices haunting the one narrative that we most often tell.

Postcard image via 99% Invisible

The complexities of this story and home do not right its owner’s many wrongs. But the Winchester House, with its many eccentricities and misgivings, does serve as a small reminder of how people may try to make sense of the guilt in its many manifestations. Sarah Winchester constructed a sprawling home on the land of those murdered by her family’s technological innovation and turned it into a bizarre but long-lasting spatial memorial to the thousands of lives ended by the Winchester gun. The Winchester House, with some critical investigation, could offer a complicated memorial approach to the dialogue on the trauma of colonization. The American landscape, through historical and contemporary space, is forever impacted and shaped by this brutal reality.

The Winchester House speaks to the need for updated interpretations of history and trauma, particularly when it comes to reflections on the colonization of Native Americans. The large-scale affective and spiritual violence against the Indigenous peoples that used to call the Western frontier home is often left out of historical narratives. Beyond the obvious effects of corralling entire populations of human beings, such as the loss of language and cultural institutions, the erasure of social structures to shape cultural advancement, and the genocide of thousands of people who once freely navigated their needs and interests across various lands and waters, the more nuanced emotional responses and long-term effects of such atrocities have also been explored. The psychic damage inflicted on the native peoples of the United States can be highlighted within the context of the Winchester House, which can be understood as a tiny example of injustice on a large timeline of ongoing violence.

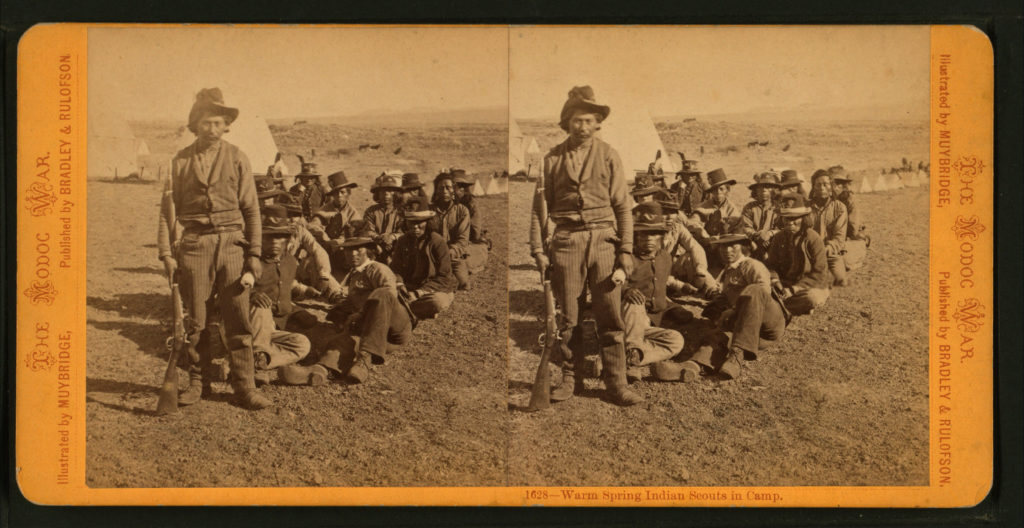

Sarah Winchester’s hauntings are not the only notable event of 19th century San Jose. It’s possible that some of the ghosts in her home were local. The Modoc War took place in Northern California from 1872-1873 and was led by Kintpuash, known as Captain Jack. As white colonists traveled west and settled in to the area, they demanded that the people indigenous to the area be sent north to the nearby Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon, where many other Klamath and Yahooskin people lived. The Modoc demanded their own space, saying that the Klamath Reservation to the north could never be home due to political disagreements with the Klamath (and also differences in climate and culture). While the Modoc War only saw two official Native American deaths, it is one of the last “Indian Wars” to take place in California, sealing a legacy of indigenous suffering and erasure. After the war ended, four Modoc men were executed and the remainder of the Modoc people were sent east to Oklahoma, far from their rightful home and land. The impacts of this conflict are ongoing: as of 2006, there were no fluent native speakers of the Modoc dialect.[6]

Eadweard Muybridge photographs of Modoc encampment via Wikimedia Commons

This conflict is thoroughly explored in Rebecca Solnit’s work River of Shadows. Edward Muybridge, the subject of the book, photographed the Modoc War. Solnit effortlessly works through the many complexities of telling his single narrative while placing it in conversation with the many other events of the era, effectively bringing together a nuanced history of technology, space, and colonialism in Northern California. It is possible to tell history in a way that is ethical, thoughtful, and appropriately complex.

People visit the Winchester Mystery House attraction, inquisitive about what was done with the fortune made by American ingenuity and the Westward Expansion. What is often left out, however, are the voices and stories of those who were killed by the gun, and the populations that were forgotten from history. By removing them from the story of the Winchester House, the violence is continually perpetuated. The massive violence done to Indigenous Americans is impossible to capture through the story of the Winchester House: a strange, historic home, threatened to be haunted with the ghosts of murder victims. The Winchester House, however, owes its patrons and visitors a more complex and nuanced understanding of Sarah Winchester’s ghosts and the erasure of Indigenous Americans from Northern California.

[1] Solnit, Rebecca, River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. New York: Penguin, 2003. 118.

[2] “The Winchester Rifle: The Gun that Won the West,” Library of Congress Science Reference Guide (Science Reference Services), accessed March 27, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/SciRefGuides/winchester-rifle.html

[3] “Sarah Winchester: Woman of Mystery,” Winchester Mystery House website, accessed March 27, 2017, http://winchestermysteryhouse.com/sarahwinchester.cfm

[4] Ibid.

[5] Said, Edward, Culture and Imperialism. London: Random House, 1993. xiii.

[6] “Modoc (Klamanth-Modoc, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages website, accessed April 1, 2017, http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~survey/languages/modoc.php

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.