“Islamic” Curatorial Futures in Two Parts

Flying carpets, benign weaponries, aerial footage from drone cameras, and defiant eyes behind the veil are no more a window into the new Middle East than snake charmers, odalisques, and sulking Moorish warriors were in the 19th century. These mirages of the other were first constructed by the European Orientalists during the age of colonial empire and again in the contemporary era by artists from the Middle East and its diaspora, who like the prominent artist Shirin Neshat occasionally suffer the titles, “self-orientalist” and “cultural informant.”[1] Despite their temporal divide, both the historical and the contemporary visual lexicons have been produced and disseminated (primarily) in the West to serve as symbols for the ways in which the West encountered the broader region of the Middle East. Yet, in the contemporary artist’s desire to symbolize life over there, a feeling of resistance and decoloniality emerges in stark contrast to the vowed colonial and racist enterprise of European Orientalism, precisely because it proclaims the undoing of imperialism through transnational movement as outlined by artist organizations e-fabia and Fuse: “We are here because you were there.”[2]

Beginning in the 19th century and bleeding out in the 20th century, Western Europe commenced a long and arduous colonial venture in the Middle Eastern and North African region (MENA), which alongside physical occupation included enforced labor, cultural appropriation and psychic violence. Save for Iran and Turkey, who resisted Western colonialism and, in turn, enacted their own forms of modernism, the cultures of the MENA region were divided and colonized by those that imagined themselves to be culturally, politically, and biologically superior. Europe believed that they had reached Enlightenment and borne its fruits while the Orient was seemingly still stuck in the past—the dreaded barbarism of the Middle Ages. In her essay, “Feeling Uncomfortable in the Nineteenth Century,” art historian Margaret S. Graves asserts that in the 19th century, for Europe to have any chance at becoming the dominant global power, the Orient had to first become a “diminished, degenerated, [and] declining” entity.[3] In other words, by actively proclaiming, “Islam was once a great medieval culture,” Islam would indeed become a medieval culture.[4]

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Snake Charmer (c. 1879). Oil on canvas, 32.9 × 48 in. Collection of The Clark. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In their cultural campaign to erode a contemporary modernity in the Orient, the Europeans enlisted writers and artists, documented and unveiled the Orient to audiences at home. During their tours, Orientalist artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, William Holman Hunt, John Frederick Lewis, and Giulio Rosati made preliminary sketches and took photographs as source material. These materials were used to craft dramatized and hyper-sexualized scenes once they were comfortable back in their own studios.[5] The resulting works were exhibited in European salons, galleries, and museums to educate the public about the backward, medievalized living conditions of the Orient. Perhaps the most memorable, if not the boldest, of these paintings was made by Jean-Léon Gérôme. The Snake Charmer is a larger-than-life painting depicting a young boy who faces a crowd of lazy and salacious old men, who seemingly stand in for the widespread wickedness of the broader region because their likeness is culled from a “range of ethnicities.”[6] Employing this particular painting as a singular icon of this period, the Palestinian-born scholar Edward Said penned an insightful and relevant treatise entitled Orientalism, which in abstract and material terms outlined representations of the colonized subject through the mind of the colonizer. Orientalism wished, Said believed, to use literary and visual arts to colonize the image of the other in a hierarchically subordinate role against which the West could measure and advance itself.[7]

Reflecting on Lord Byron’s narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, in which Byron describes his alter-ego Harold’s travels in the Orient, Saree Makdisi writes, “Harold’s arrival in the East represents a passage across a multidimensional ‘border’ into the space and time of the Orient, a spacetime that has its own distinct pattern of temporal ruptures and losses, but, on its own terms, is a discrete spatialtemporal sphere, different from that of the West which Harold leaves behind.”[8] In re-reading Byron’s spatialization of the Orient in contrast to the West, Makdisi proposes an alternative view of Oriental time—containing its own past, present, and future—that can be useful for interpreting Sara Raza’s exhibition But a Storm is Blowing From Paradise. She works to show that while the concerns of the colonial past occupy people there, they are also grappling with new and renewed conditions like rapid globalization (both voluntary and enforced). In the space of the museum, a border is erected between the contemporary art objects, historical documents/artifacts, and the neoclassical architecture. The entanglement between these specific periods suggests that as a post-colonial and diasporic people, we have access to the contours of multiple histories and are able to navigate our own future.

In the fraught field of so-called “Islamic” contemporary art, the stakes were undoubtedly high for Sara Raza, who was chosen as the third and final curator for the Guggenheim UBS Map Global Art Initiative and Purchase Fund.[9] Following on the heels of two successful international projects that focused on the regions of South and Southeast Asia and on Latin America, Raza was tasked with acquiring work from the Middle East, North Africa, and their diasporic artists for the Guggenheim collection; the scope of her work included curating an exhibition of select works, which after its premiere at the Guggenheim in New York would tour to the region of its focus.[10] This exhibition, But a Storm is Blowing from Paradise, faced tumultuous conditions after it failed to secure a location in the Middle East or North Africa: the planned tour of the Pera Museum in Istanbul as well as the less appropriate Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai were both scrapped discreetly and without public discussion. Perhaps these cancellations were a result of the broader American political relations with the East, or they signalled unwillingness on the part of state-funded Turkish and Chinese museums to exhibit radical evocations from the MENA region, which included the divisive topics of the Arab Spring and Israeli settler-colonialism. Nevertheless, the Guggenheim’s decision to publicly avoid discussing not just one but two cancelled exhibitions was irresponsible. With such exhausted beginnings, But a Storm is Blowing from Paradise and the broader Guggenheim UBS initiative was completed in Milan, Italy, one of the tertiary centers of the old art world that the project might have wanted to move away from rather than toward.

Removed from the sanitized white-cube environment of the Guggenheim Museum, the work of thirteen artists is now set on the ground floor of the neoclassical architecture of Milan’s Galleria d’Arte Moderna (GAM). And lo, what I anticipated to be my greatest discomfort with the exhibition became its shining glory: every room was equipped with an extravagant chandelier that hung like a dead elephant—upside down, with its guts spilling out.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Latent Images, Diary of a Photographer, 177 Days of Performance, 2015. 354 copies of printed artist’s book, 177 metal shelves, and color video, with sound, 120 min; Dimensions variable. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund 2015.88. © Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. Installation view: But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, April 11-June 17, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: Noor Bhangu.

The title But a Storm is Blowing from Paradise is taken directly from the work of one of the exhibiting artists, Rokni Haerizadeh, and can be traced back to Walter Benjamin’s impassioned review of Paul Klee’s print Angelus Novus. Of the figure, Benjamin wrote:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back his turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. The storm is what we call progress.[11]

While Benjamin’s piece of imaginative art writing was not necessarily a starting point for Raza’s curatorial organizing, her curation does link history, progress, and the flow of chaos. In Raza’s exhibition essay, she describes how the chaotic is tamed and channelled through this mediated “elastic curatorial framework” that does not entirely depend on creating an overarching narrative, but rather a network of “cross-cultural critical thinking, wherein several urgent issues inform one another.”[12] Thinking broadly about global migration, architectures, and human life shifting between these structures, Raza put together a smart project that in many ways continues to spill out of its exhibitionary container. The artists, for their part, come to embody this elasticity by stretching in and out of the conversation while keeping their own voice strong.

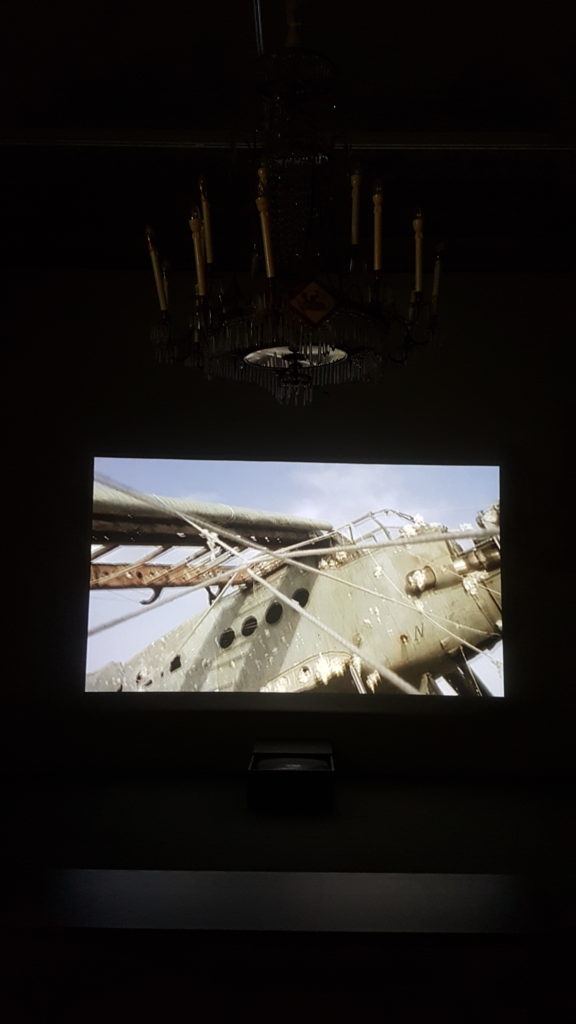

Lida Abdul, In Transit, 2008. Color video, with sound, transferred from 16 mm film, 4 min., 55 sec., edition 3/5. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund 2015.82. © Lida Abdul. Installation view: But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, April 11-June 17, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: Noor Bhangu.

The first gallery of the exhibition houses a projection of Lida Abdul’s video In Transit (2008). A group of small Afghani children, carrying shapeless strands of cotton and thin lines of rope, are seen playing around a fallen aircraft in an attempt to revive the ruinous metallic entity. The work visually expresses the parable-like nature of New Wave Iranian cinema; the young actors stand in for the Afghani people that, even without means of reparation, are vigilant in their desire to rebuild from the wreckage of America’s wave of progress: the Afghanistan War. The optimism of these Afghani children is like that hope held by all and always-vulnerable children of post-colonialism, who in working against historical and contemporary orientalisms are enrolled in never-ending psychic and cultural repair. With the resilience of cotton and rope, we too reiterate the artist’s statement: “anything is possible when everything is lost.”[13]

Near the end of the exhibition comes another work that is actively engaged in a dialogue with the past. Khader Attia’s Untitled (Ghardaïa) (2009) consists of a model city formed from couscous with appropriated photographic portraits of two modern architects, Le Corbusier and Fernand Pouillon. As a French artist of Algerian descent, Attia’s work responds to the history of French occupation and colonial theft in Algeria. French architects borrowed/stole much of their modernist aesthetics and geometrics from the M’zab region of Algeria, where Ghardaïa, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site is located, without feeling the need to cite these origins. Attia is quoted in Raza’s exhibition essay: “Lack of quotation…is lack of acknowledgement.”

Kader Attia, Untitled (Ghardaïa), 2009. Couscous, two inkjet prints, and five photocopy prints; Couscous diameter: 500 cm; inkjet prints: 180 x 100 cm and 150 x 100 cm; photocopy prints: 150 x 100 cm Edition 2/3. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund 2015.84. © Kader Attia. Installation view: But a Storm Is Blowing from Paradise: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, April 11-June 17, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: Noor Bhangu.

Securely resting on the decolonial demand for knowledge repatriation, Attia’s thoroughly sensorial project works on multiple levels. Before the visitor has a chance to encounter the full work, the warm and slightly stale stench of couscous descends upon them. In this way, Untitled (Ghardaïa) starkly reminds us of the real-life materiality of the work, whose use of staple food emphasizes the lived realities of the people that have been bound by colonial architectures. Once past the olfactory assault, it becomes possible to unpack the subtler magic of the couscous structure, which from a hard-lined formation at the top moves to soft crumbles at the margins of the city. I suspect that the binary distinction between hard and soft is a link to parsing the relationship between the couscous city with the portraits of Le Corbusier and Fernand Pouillon. It appears that the projected crumbling materiality of the city is a way for the artist to counter the hegemonic authority and historicity of the photographic portrait with a return to a cultural past, once recorded by early Orientalists like Gérôme and again by plagiaristic modernists like Le Corbusier, and is resurrected in the GAM to state, “

In 2013, a collaborative think tank between e-fabia and Fuse resulted in a “Decolonial Aesthetics Manifesto,” which outlined the potential of decolonial artists as such: “They are aware of the confinement that Euro-centered concepts of art and aesthetics have imposed on them. They have engaged in transnational identities-in-politics, revamping identities that have been discredited in modern systems of classification.”[14] This move rings especially true for But a Storm is Blowing From Paradise. As Edward Said said, Orientalism is never finished and instead reinvents itself in every age, according to its new contexts. Knowing this—that Orientalism, like Colonialism, pulsates in a new flow and vigor in our own epoch—the impulse is not to locate it but to understand how we can care for ourselves inside of it. As Sara Raza and the artists of But a Storm is Blowing From Paradise show us: resistance can be futile if it is not mediated by (perhaps blind) optimism.

[1] Lindsey “Frayed Connections, Fraught Projections: The Troubling Work of Shirin Neshat.” Women: A Cultural Review 13, no. 1 (January 2002): 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1080/095740400210122959

[2] E-fagia and FUSE, States of Post Coloniality/Decolonial Aesthetics. (Toronto: Artons Cultural Affairs Society and Publishing Inc, 2013), 10.

[3] Margaret S. Graves. “Feeling uncomfortable in the nineteenth century.” Journal of Art Historiography. (2012): 1-27. p. 18.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Gabriel P. Weisberg, “The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904).” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, January 1, 2010. http://www.19thcartworldwide.org/autumn10/thespectacular-art-of-jean-leon-gerome-18241904.

[6] “Jean-Léon Gérôme: The Snake Charmer.” The Clark. http://www.clarkart.edu/Collection/559.

[7] Edward W. Said. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

[8] Saree Makdis, “Versions of the East: Byron, Shelley, and the Orient,” in Romantic Imperialism: Universal Empire And the Culture of Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 205.

[9] The expansive project was set up between the Guggenheim Museum and the Switzerland-based bank UBS.

[10] In the years 2013 and 2014, No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia traveled to the Asia Society Hong Kong Center and the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. In 2016, Under the Same Sun was presented at Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

[11] Stuart Jeffries, “The Storm Blowing from Paradise: Walter Benjamin and Klee’s Angelus Novus.” Verso (blog), August 2, 2016. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2791-the-storm-blowing-from-paradise-walter-benjamin-and-klee-s-angelus-novus.

[12] Sara Raza, “Exhibition Essay.” In Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative: Volume 3: Middle East and North Africa. (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2018).

[13] Ibid.

[14] E-fagia and FUSE, States of Post Coloniality/Decolonial Aesthetics.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.