The Exclusion Games: Olympic Exceptionalism in Rio de Janeiro

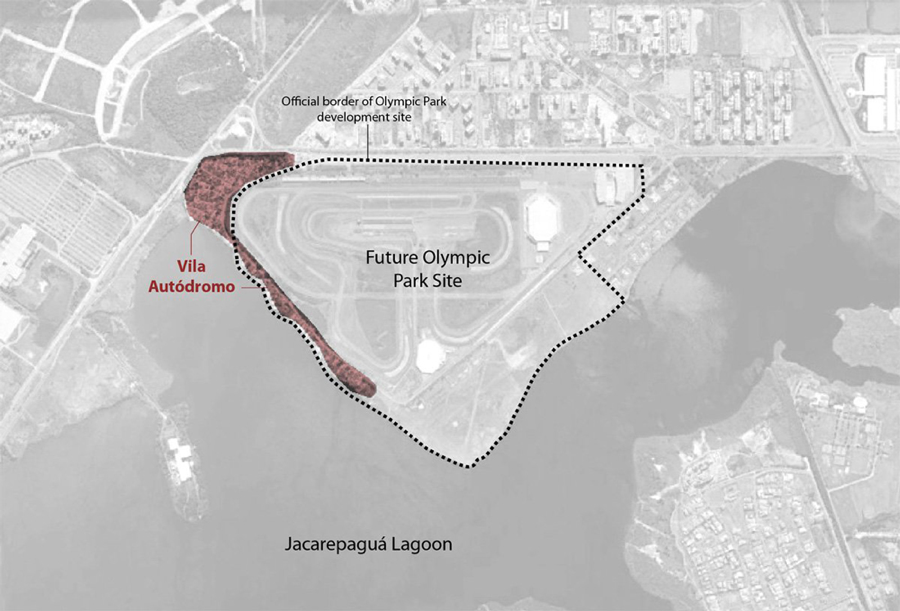

In the lower part of the image the favela Vila Autódromo is shown prior to demolitions. Above that the preparations for Barra Olympic Park are underway.

It is not a matter of if anti-Olympic protests will occur. According to the community reporting website Rio On Watch, a large group of demonstrators are scheduled to assemble despite the recent criminalization of social movement gatherings, despite the shocking militarization of the Games, and despite an overall lack of interest by mainstream media in the demoralizing toll the Olympics have had on the city’s most vulnerable citizens. The opening ceremonies, arranged to take place at Maracanã stadium on August 5th, will be a focal point for an array of activists united under the critical slogan, “The Exclusion Games.” Rio’s Olympics have been widely publicized as the “Games of Inclusion,” a phrase that lends itself almost seamlessly to the opposition’s ironic appropriation. Both the president of the International Olympic Committee and Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, have referred to the Games as socially tolerant and indicative of a harmonious Brazil, qualities that properly represent the Olympic ideal of international cooperation—no matter how fleeting and superficial. This kind of inversion of language, whereby the state’s theoretical use of the word “inclusion” is revealed to mean in practice “exclusion of the poor at any and all costs,” could not be more telling in the dystopic seven-year lead-up to the Games.

As has been written again and again by numerous human rights watch groups, marginalized neighborhood associations, and socially engaged media, there is more than enough to protest at this year’s Games. Too much perhaps. The rising levels of social injustice, political maneuvering, state-sanctioned repression, and back-room real estate dealings are both deeply convoluted and deeply troubling. Amidst all the obscurity, one thing is certain: the Games have absolutely accelerated brazen and unapologetic collusion between corporate interests, government administration, and militarized security forces, the goal of which is to produce massive-scale outcomes that benefit Brazil’s already over-privileged social and financial elite as well as to instate and maintain a right-leaning government responsive to neoliberal global finance schemes that commonly sacrifice the general population’s well-being.

On the surface the Rio Olympics have become a powerful justification, a guise under which all manner of projects are pushed through wide-spread protestation in right wing hardline fashion—literally razing, dividing, and selling public lands to developers cheaply for the consolidation of future private wealth. The so-called legacy projects associated with the Games are the opaque, yet highly visible, engines driving a host of tightly wound interactions between mogul developers and the highest ranked Brazilian politicians. Olympic legacy projects are infrastructure renewal undertakings and large-scale urban additions made in anticipation of the expected Olympic crowds. Over ten thousand athletes and half a million spectators are estimated to visit Rio during the Games. These specific types of ventures supposedly have positive long-term effects for the host city’s population—a massive wake of infrastructural upgrading left by an Olympic behemoth. In the case of the Rio Games this includes, among others things, two major real estate development schemes, the construction of a variety of sporting venues, a major environmental cleanup of Rio’s disastrously polluted waterways, and an expansion of public transportation, all of which have been implicated in various corruption investigations.

As billions are spent, including billions of public funds, on modernizing tourist centers linked to the future sites of luxury condominiums and apartments, the rest of Rio is undergoing severe austerity measures that include funding cuts to hospitals and education institutions that serve the poor. At one of the many centers of the Olympic infrastructure investigations is the state-run oil company Petrobras, which underwent its own corruption scandal in 2014, resulting in top executives and politicians jailed for bribery and money laundering. Scrutiny of Petrobras guided investigators to a handful of construction firms associated with Olympic venue build outs. Among the officials caught up in the Petrobras “Lava Jato” scandal is Michel Temer, the interim president of Brazil, along with members of his all white, all male administration who are hostile to labor rights and pro-privatization of public services and infrastructure. Essentially, Temer’s right wing government is seen as serving its corporate sponsors, paying back sizable election contributions with sympathetic public policy.

Temer replaced ousted Worker’s Party president Dilma Rousseff, who was stripped of the high seat in May following allegations that she covered up Brazil’s growing deficit. The Worker’s Party, established in response to a military government that ruled from 1964 to 1984, has traditionally protected Brazil against multinational, corporate-friendly policy. Although many believe that the allegations against Rousseff have been fabricated, her decline has nonetheless occurred; she was challenged equally on the streets and behind the closed doors of powerful political manipulators. A deep recession sparked by a fall in oil prices and harsh global markets set against Brazil’s deficit-saddled economy propelled the middle class downward, creating a mood of disappointment and dissatisfaction that ended with a right wing administrative presidential take over. The Olympic bid was awarded in 2009, two years before the historical recession, during a moment of financial wellbeing and optimism, a national market unaware of its own impending collapse. In addition, various media corporations have been criticized for intentionally focusing on demonstrations to expel Rousseff, ignoring large protests by Rousseff supporters. Response to the new, unelectable, conservative administration headed by Temer has been mixed. Latin American countries acquainted with U.S. interventionism denounced the ousting as a neoliberal coup masterminded by U.S. foreign policy and corporate interests. Venezuela, Ecuador, and El Salvador withdrew their ambassadors from Brazil in response. With a chilling effect, the overthrow closely follows a pattern of U.S.-based intrusion all too familiar in Central America. A series of audio recordings eventually surfaced revealing the ousters’ plot for what it was, a conspiracy to end the Petrobras corruption scandal and seize power at the same time.

This map shows the official outline of the Barra Olympic Park with Vila Autódromo in red.

One of the places where activists and housing right protesters have caused international embarrassment for Olympic real estate moguls, as well as for Mayor Paes and President Temer, is a small favela called Vila Autódromo that borders the northwest section of the Barra Olympic Park, a campus-like arrangement of venues, facilities, and sporting structures on Lake Jacarepaguá. A set of maps used in the bid for the Games shows three phases of development for the Olympic Park. In the image marked 2016, the park appears fully functional for the Games—arenas, sports fields, and other venues are all in place. The 2018 map shows the area in transition. The map depicting 2030 illustrates the legacy space fully converted into a series of high-rise luxury apartments buttressed with tree-lined green spaces. The post-Olympic development, to be called “Ilha Pura,” meaning Pure Island, was conceived of as a bastion for the elite classes, most definitely not a place for the poor. At the same time, Vila Autódromo appears intact in all three maps with only modest loss of land. However, the images used to garner the Olympic bid have gone the way of the Olympic motto, just another instance where the authorities say one thing and mean the opposite. Clearly, if the Olympic Park area is to be repurposed after the Games for over 3,000 private apartments costing up to 700,000 US each, it is a space that cannot be closely bordered by a low-income neighborhood considered to be both an eyesore and a security problem.

This map from the Olympic bid shows the park development projected for 2016 fully functional for the Olympic Games with Vila Autódromo intact.

This map from the Olympic bid shows the park development as it will appear in 2018 undergoing transition from sports use into domestic use with Vila Autódromo intact.

This map from the Olympic bid shows the park development as it will appear in 2030 fully transitioned into domestic use with high-rise luxury apartments and Vila Autódromo intact.

Indeed, “security” is an Olympic watchword, another all-inclusive term invoked to justify whatever extremes are required to settle the city in anticipation of projection onto a global stage. According to Amnesty International, as of June 65,000 police officers and 20,000 military soldiers have been deployed to guard the Olympic Games. Another 2015 report accuses security forces in Brazil of frequently using excessive force and extrajudicial executions without accountability. The phrase “resistance followed by death” refers to police killing justified as self-defense and is used as a blanket explanation allowing security forces to cover up illegal assassinations with impunity. Part of the Olympic ramp-up beginning in 2009 included the establishment of Pacification Police Units in the city’s favelas. The pacification units were imagined as a long-term, community-based, security solution theoretically accompanied by an increase in social services—all of which have been gutted in the economic downturn. In the wake of pacification failure, the police themselves have been under severe examination, as more and more are accused of collaborating with the drug cartels they are supposed to be thwarting, patrolling main streets while leaving smaller thoroughfares intentionally unattended.

The Games, coupled with an overall heightened sense of danger and insecurity worldwide, have put considerable stress on the state to curtail criminal and terrorist networks, often by any means. Brazilian military forces are under criticism for killing favela children in an effort to present a trouble-free zone in anticipation of the Olympic celebrations. Police corruption has been somewhat explained away by frozen salaries, another fiscal casualty of Brazil’s ongoing economic crisis. And while security measures for the benefit of incoming tourists have increased, the result is an overall decrease in security for those living in the poorest parts of the city under the constant and relatively unmonitored threat of state-sanctioned violence. Additionally, Brazil’s recently approved anti-terrorism law, criticized as controversially vague, has been condemned by the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights in South America as an open door to civil rights violations. And while the new anti-terrorism laws were devised to stymie large land reform movements like the Movement of Landless Peasants (MST), they have been cited as alarming to Olympic protesters apprehensive as to how their actions might be juridically interpreted as terrorism.

In 1994, the residents of Vila Autódromo were awarded ninety-nine year titles to their lands. While authorities promised to spare the neighborhood from Olympic absorption on multiple occasions, including in the form of the maps used to visually communicate the layout and concept of the Barra Olympic Park, eventually the economic stakes of urban renewal, as opposed to urban upgrades, took precedence. In March of 2015 eminent domain was invoked, followed by a campaign of illegal lightening evictions accompanied by shock troops. Last summer saw violent clashes between riot police and residents who refused to leave their homes. How can one reconcile the forced removal of families from their life-long homes for such a transitory peripatetic event, no matter how spectacular? Well-known housing rights activist and resident of Vila Autódromo Maria da Penha had her home destroyed without notice on International Women’s Day, the same day she was to receive the Woman Citizen award at Rio’s State Assembly. Early in the morning troops took down part of the fence that separates the favela from the Olympic development in order to gain the element of surprise. In a devious media stunt designed to detract from the housing rights movement, Mayor Paes scheduled a press release that coincided with the award ceremony under the auspices of sharing the city’s new upgrade plan for Vila Autódromo—a plan no resident of the favela had heard of before. Ironically, the residents of Vila Autódromo fabricated an award-winning proposal of their own (one shared with the city), developed by community members along with urban planners from Rio’s federal universities that outlined alternatives to forced removal. When residents showed up to stage a counter press conference outside the Mayor’s Palace, Paes moved his conference, preventing any form of dialogue or questioning. At the end of July, the remaining twenty families (once six hundred strong) received the keys to new homes inside the flattened favela as promised by Rio authorities. After years of struggle against real estate interests, military harassment, and governmental deception, the razing, dividing, and selling-off was done.

Google Street View showing the Vila Autódromo in August 2014.

Google Street View showing the Vila Autódromo in August 2014.

Google Street View showing Vila Autódromo and the Olympic development in August 2014.

Google Street View showing Vila Autódromo and the Olympic development in August 2014.

Google Street View showing Vila Autódromo and the Olympic development in August 2014.

In August of 2014, Google sent its infamous Street View car through Vila Autódromo, which now serves, for the time being at any rate, as an archive of what the neighborhood looked like right before the forced evictions were fast-tracked. In screenshots taken of a digital stroll through the neighborhood one can see flowers and plants blooming and climbing over quaint wooden doors, people walking, and just over the corrugated metal fence, the construction of the Olympic Park that would eventually be the community’s demise. White cement trucks line the entrance to the neighborhood, cranes loom in the distance, the shells of impending Olympic-related infrastructure are close enough to hit with a rock. In another image, a large pile of graded earth can be seen peeking over the fence. For me these images act as a way to modestly begin to understand what it must have been like to live in the shadow of an urban development backed by the wealthiest and most powerful elites, a development aimed at a vulnerable community seen as acceptable collateral damage. A view of Vila Autódromo on Google Earth tells a different story. The twenty new state-sanctioned homes are incomplete while the surrounding area is leveled and cleared of debris. In each case the Internet, often thought of erroneously as a place of permanence, shows us something about ephemerality, about a neighborhood that was in the wrong place at the right time. And while authorities are busy glibly declaring the unprecedented transformation of Rio, it is clearly not a transformation for the benefit of everyone, especially not for those made to literally disappear.

Google Earth View showing Vila Autódromo after demolition in the top left hand corner of the image.

Google Earth View showing Vila Autódromo in close-up after demolition.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.