Dogs and Racism in America

Attorney Kenneth Phillips specializes in dog bite law. Visit his website, and you can find a short blog post in which Phillips addresses the issue of breed-specific legislation (BSL), which bans or places special restrictions on breeds that are supposedly prone to aggression. This is the type of legislation that makes it impossible for you to adopt a Rottweiler or a Doberman if you live in certain parts of the world.

Some critics of BSL liken it to racism, but Phillips thinks this is ludicrous.

“Invoking the fight against racism is not only irrational but also a slap in the face of anyone who seriously opposes discrimination against people based upon the color of their skin….The making of such a comparison is a tip-off to the extreme lengths that the dog lobby will go in order to avoid the common-sense regulation of killer dogs and their dangerous owners.”[1]

At first read this seems fair. Breed-specific discrimination is in many ways incomparable to the problem of racism among human beings. Marginalized people face social and emotional struggles with which dogs could not identify.

But the philosophical tipping point in this passage comes at the very end: “killer dogs and their dangerous owners.”

This passage might be problematic in the eyes of a social psychologist. Who are these killer dogs? What kind of people own them? Where do these people come from, and how do dogs become killers, owners dangerous?

It is here that I’m drawn to the insights of Vicki Hearne, a popular animal trainer in the 1980s and 90s. Hearne published multiple books on the complexities of animals. Her perspective was unique in its poetic roots; Hearne’s literary and philosophical backgrounds merged with a long career in animal training. Her ideas manifested in writings that celebrate the spiritual history of domestic creatures, and her style of thinking challenges us to notice rich layers of animal potential.

Hearne wrote poetry, novels, and philosophical nonfiction.

Hearne is immortalized on film in the 1991 documentary A Little Vicious, directed by Immy Humes. The film serves as a companion to Hearne’s book Bandit: Dossier of a Dangerous Dog, which was published in the same year. Both tell the story of how Hearne rehabilitated and eventually adopted a bulldog who was put on death row for biting two people.

Beneath the events of this story are lessons about race and myth, about the hyperopia that leads us to make judgments about certain types of beings without knowing much about them.

One such judgment is the assumption that Bandit, the dog at the center of the drama, was a pit bull. He was not. But the media uproar that surrounded the story embraced a burgeoning reputation the pit bull had garnered for being more dangerous than other breeds. As a result, common knowledge had it that Bandit was a pit bull—or, at the very least he had “ties to the pit bull family.” His breed became relevant because of the viciousness it implied for the populace.

Bandit was registered as an “honorary pitbull.” His registered name was Definitely Bandit.

But Hearne wants us to notice that Bandit’s reputation—which spans multiple breeds of broad-chested, short-haired, bull-baiting, fighting dogs—does not just apply to pit-bull-like things, and it does not just apply to other notoriously “vicious” dogs. Its origin and perpetuation is intricately tied in with another factor: who owns these dogs. Or, more accurately, who we think owns these dogs.

In the 1980s, not long before Bandit’s ordeal, the United States saw a notable rise in the popularity of dog fighting. Pit bulls (and other “bully breeds” that resemble them) became the face of the sport, which was associated with deviants, thugs, and back-alley ghetto culture. In other words, pit bulls and dog fighting came to be associated with black people. This has been evident as recently as the Michael Vick scandal and the outrage surrounding it. As the breed’s current reputation makes clear, this association has not been a favorable one.

This unfavorable reputation stands in contrast to what the breed used to symbolize in the United States. For many years, the pit bull was considered the all-American dog, much the way Labradors and Golden Retrievers are viewed today. They were widely popular as family companions and guardians, television stars, and working military dogs. Because of their dependable and steadfast nature, pit bulls and other bulldogs embodied the ideals of American culture. They fit the role of the exemplary American so well that their likeness was used to represent the United States in World War I posters.

“We’re not looking for trouble, but we’re ready for it.”

It was a spiritual connection, that of the American and the bulldog. But the history of Americana has been dominated by the values of white families and their communities. When the pit bull moved from Mayberry to Harlem, his cultural identity changed dramatically. It is here that words like “vicious” come into play as a common descriptor of the pit bull. A major theme of Hearne’s musings about Bandit is the concept of viciousness and the ways in which we apply the notion to animals and people. She says in the documentary:

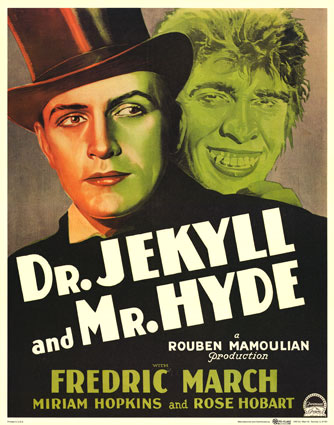

One of the entrancing things that people say about pit bulls is that they are subject to something called the Jekyll-Hyde syndrome…On the one hand you have a stuffed animal, and on the other hand you have a monster. And this has all sorts of parallels in the stories we tell about people. For example, the gentle, devoted, faithful black servant as opposed to the marauding, raping nigger carrying the knives with all the scars on him…Or the woman as bitch and woman as goddess notion. It’s just something people do instead of thinking.

“Thinking” here implies some awareness that human and animal behavior is reasonable when taken in context. To suppose that a creature is bound to behave unpredictably is to withhold from that creature the capacity to act reasonably. Thus it withholds a certain degree of complexity and even personhood.

Why, for example, might Bandit have bitten two people, one being his owner? One explanation is the Jekyll-Hyde hypothesis, which promises that a pit bull will eventually “turn on you” at any moment because of his biology.

Hearne and I would like to emphasize that “Jekyll-Hyde syndrome” is borne from fantasy fiction.

But look more closely at the stories behind Bandit’s behavior and the bites start to make more sense. The first bite was in Effie Powell’s leg. Bandit had been sitting on his owner Lamon Redd’s porch, next door to a house Redd rented out. Powell came to the rental house to visit the tenant, her daughter, whose boyfriend was present. When Powell became angry with the boyfriend, she chased him out of the house and down an alley with a broom. Bandit promptly leapt off Redd’s porch and into Powell.

Bandit was then taken and confined by local canine control until Redd built a $3,000 fence around his property. When Bandit returned home, his housetraining suffered. Redd admitted to beating Bandit with a stick for as long as five minutes before Bandit clamped onto his arm.

“I was the cause of that,” Redd says in the documentary. “That’s the reason I fight for him.”

Redd adamantly opposed the death sentence placed on Bandit after the second bite and demanded that the dog be returned to him. In A Little Vicious, Redd’s daughter Lily Mae speaks in the dog’s favor regarding Powell’s bite: “Bandit didn’t even move off the porch when [Powell] come in. But when she come back with that broom and drawed it back at that boy, that’s when he jumped up and jumped on her ass, because she was disturbing the peace.”

While animal control and the media buzzed about unpredictable monsters and naturally aggressive breeds, Bandit’s housemates saw plenty of sense in the dog’s behavior. In fact, they sang his praises despite having felt his teeth. “Bandit’s a good dog. Bandit’s a baby,” Lily Mae says. Bandit’s intelligence and nobility shone through to those who knew him best. It was precisely that tenacious American spirit that was so inspiring about him. Even after rehabilitating and training him, Hearne claims her goal was never to tame Bandit to the point of passiveness: “Breaking him of what made him bite Effie Powell—if the prosecution’s worst-case version of it is accurate—is breaking him of being a creature, of loyalty and courage and all of that.”

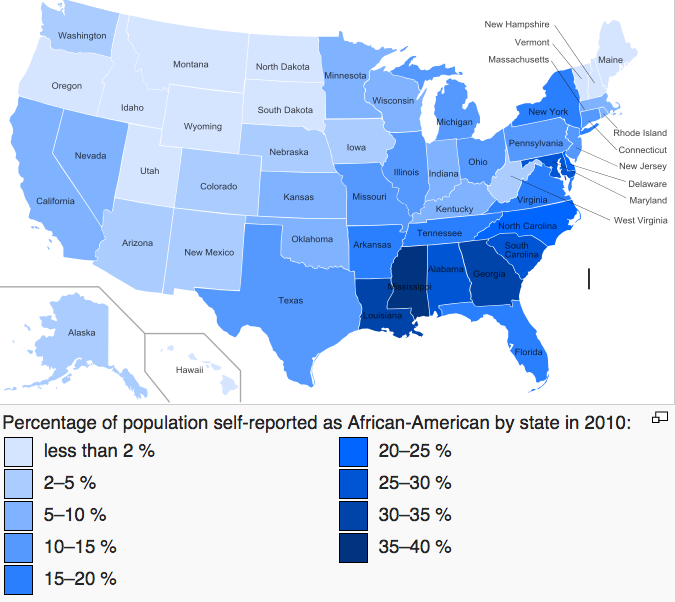

For much of the public, these traits remain obscured in pit bulls today. Even as the breed has regained some admiration as a family and working dog, the stain from their days as ghetto pups is hard to wash out. Fortunately for pit bulls, they’re able to hop about popular culture and take on nobler meanings; they’re able to return to white America and become something a bit whiter. The Michael Vick dogs have made this shift quite literally, from Vick’s house in Virginia to the Dogtown rehabilitation center in Utah.

By population, Virginia is about 20 times blacker than Utah.

Blackness still means much the same thing it did thirty years ago, sixty years ago, one hundred, two hundred. Joel Kovel discusses the intertwining of “blackness” and “whiteness” at length in his 1984 book White Racism: A Psychohistory. He points out that these two terms don’t literally refer to skin color, but rather our learned and automatic perceptions of what skin color signifies. The meaning of one is predicated on the meaning of the other. “Blackness is otherness,” Kovel says. “The racist relation is one… in which the white self is created out of the violation of the black self, through its inclusion and degradation. Racism degrades the Other to constitute the dominant self, and its social order.”[2]

This degradation—the myth of viciousness—continuously works on subliminal levels to keep black America out of power. None of this excuses the behavior of Vick and his colleagues, but it’s important to remember that Vick doesn’t have the luxury of speaking for only himself. This is the plight of the Other, who is not granted individuality but is subject to myths about his “kind.” Just as Bandit’s bites spoke for his breed, Vick’s actions spoke for his race.

We’ve seen what the myth of viciousness is obscuring in pit bulls. What, then, is it obscuring in black America? As marginalized and underprivileged as African Americans still are, what should our society be looking to “improve” about their lives, and what should we be looking to preserve? The black community—those who know black Americans best—will tell you there’s loyalty, courage, steadfastness long waiting to be uncovered. It falls on outsiders in power to see it for themselves.

Bandit’s story is an anecdote about the importance of story itself. To learn what viciousness is obscuring, one must learn the stories of the vicious, of “killer dogs and their dangerous owners,” and uncover what complexities lie beneath the illusion. We take for granted that there is complexity in there somewhere, so long as we take for granted that these creatures are whole and, on some level, like us. When we assume otherwise, “viciousness” is a much easier way to think about creatures we don’t understand.

[1] Kenneth M. Phillips, “’Racism against dogs…’ – come again?” Dog Bite Law (blog), accessed August 16, 2016. https://dogbitelaw.com/blog/racism-against-dogs-come-again

[2] Joel Kovel, White Racism: A Psychohistory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), xliii quoted in Juan F. Perea, “The Black/White Binary Paradigm of Race: The Normal Science of American Racial Thought,” California Law Review 85, no. 5 (October 1997): 148-49.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.