Dead Celebs

On August 11, 2014, I was getting a beer with a friend after work, trying to make sense of relationships and work. We were in a basement bar in downtown Chicago, thankful for air-conditioning. CNN was on the televisions, playing random clips of video about new developments in the Middle East. We mostly ignored the TVs and casually sipped on our beer. The bottom of the television screens began to flash with “Breaking News.” Robin Williams had been found dead. The bar became silent and we all watched anxiously as the story unfolded. Most people started to cry, just a little bit. I also did, but more so later at home, silently and by myself. I even cried on the phone when I called one of my best friends, Amey, with whom I used to watch Mrs. Doubtfire when we were kids.

On January 11, 2016, I was able to sleep in later than usual so that I could stay late for a meeting at work. My alarm went off and NPR came on. I wake up to NPR every day, and despite it generally announcing the horrible goings-on in the world, I really love waking up and listening to the news. For once, I woke up and didnʼt hear about Syria, or Donald Trump, or shootings in Chicago. While these events are all worth discussing and thinking, I found the tiniest bit of solace in NPR that morning, because they were playing David Bowie. I lay quietly listening to “Heroes,” which was cut short by the radio host asking listeners to call in and share their favorite Bowie memories along with what he meant to them. He then announced that Bowie had died the day before. I weirdly cried for a stranger, and the train on the way to work was quiet.

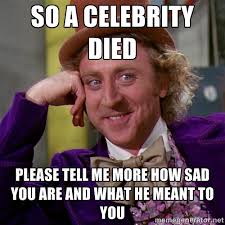

Both times, I felt a sense of discomfort in the intensity with which I responded to the deaths of these actual strangers. I felt embarrassed to tell my friends, who in turn, were also embarrassed to tell me that they, too, were hit intensely by these losses. I knew I shouldnʼt feel embarrassed, but I still felt that particular anxiety for when you have feelings that you think maybe you should not have. For a culture that reminds us that mourning ought to be private, contained, and limited to specific relationships such as parents and lovers, conceptualizing mourning as an ongoing and boundless experience is often frowned upon. Positing that humans react to the loss of strangers who enter their homes through media and memory is frowned upon at best.

In many ways, the dialogue and construction of arguments attempting to make sense of the impact of this loss takes place online. In this way, and in many others, the internet as social platform is a constant reminder that the ability to anonymously share our thoughts is widespread and accessible. If weʼre looking for validation of one particular kind of view point, itʼs out there, somewhere.

In this case, it seems that criticism of mourning is abundant and widespread. The internet catches the minutia of our daily goings-on, and it is there to document and make sense of the instances of workings-through, partial and whole truths. This is especially poignant in the case of working through loss and mourning, regardless of scale. Grief has the potential to cultivate connection and community; it validates our sense of loss by sharing our connections. The “#RIPBOWIE” on Twitter is relevant evidence to this: an outpouring of photos, one-lined memories of Bowie from across the world, poignant song lyrics.

When an incredibly well-known celebrity dies, reactions pour out. While there is certainly an abundance of sentimental outpourings and reflections on the loss, there is also “grief shaming” that claims grief as a tangible experience only when it is for someone that we knew in a deep and intimate way. Celebrities or public figures are seen as simply not worth it, or grief is understood as an unhealthy reaction. I disagree.

A piece published by the Washington Post in 2012 after the death of former BeeGee Robin Gibb, “Tweet it and weep? Online, grief over dead celebrities is about us,” outlines the two major issues with grief shaming: the competition between grief experiences and the negative connotation of grief with self-indulgence. Providing further evidence of grief shaming, the public comment areas of articles about grief online offer a plethora of callous and generally rude responses to online expressions of emotions.

In the realm of digital grief shaming, as the Washington Post piece states almost immediately, memory sharers often aim to out-mourn all other mourners. The “Paul Reveres” who are the first to share the news of the death, and the following wave of first responders, are over-eager claim that their experiences related to the newly dead are more nostalgic and more meaningful than othersʼ. In this world, grief exists in layers that are logical and identifiable.

In reality, however, grief is not something that can be explicitly quantified. A grief competition is bizarre because competition is defined by the ability to defeat others who are working towards the same end goal. But grief is not something to be won or attained; it is an unlimited process. Mourning is not an end goal, and processing emotional pain is deeply individualized and responsive to our own experiences and worlds.

In reality, however, grief is not something that can be explicitly quantified. A grief competition is bizarre because competition is defined by the ability to defeat others who are working towards the same end goal. But grief is not something to be won or attained; it is an unlimited process. Mourning is not an end goal, and processing emotional pain is deeply individualized and responsive to our own experiences and worlds.

If grief cannot be a competition, than the first accusation in online grief shaming is false. There is no way in which sharing grief should instigate a hierarchy in which one personʼs experiences are more valid than anotherʼs. This is relevant not only to collective or large-scale mourning but in the day-to-day: our responses to every encounter in life are valid and meaningful. Grief shaming works in opposition to this.

The second component of online grief shaming is that mourning for the loss of a celebrity is selfish and vain. This approach paints grievers as self-serving and egocentric, caring only about their own experiences. As the author in the Washington Post says, “The more you grieve, the more special you are.” This statement implies that responding to the death of a celebrity with grief is evidence of self-absorption, and that those less affected by this loss are somehow morally superior. It reminds us that experiencing grief automatically puts you on the defensive, that you must somehow remind everyone else that you deserve to feel sadness for loss, and that your explanation is open to scrutiny. Any display of vulnerability is unwelcomed and worth judging. But grief does not make you special or selfish, because grief and sadness are not exceptional or unique feelings.

This Washington Post illustrates an accusational response to processing grief for a celebrity. Grief should be selfish, in not in a way that is disparaging, but in a way that elevates self-care as a necessary and fulfilling action. Dealing with loss will always be difficult territory, and one on which we never choose to embark. We must often handle it alone. With this large-scale or collective mourning, we trudge forward in cultural melancholy with the opportunity for a collaborative healing. We can make sense of loss and what it means for each of our past, current, and future selves. If social media makes a space to process this in a collective and social matter, than demonizing it is simply unhelpful to the process of grieving.

This Washington Post illustrates an accusational response to processing grief for a celebrity. Grief should be selfish, in not in a way that is disparaging, but in a way that elevates self-care as a necessary and fulfilling action. Dealing with loss will always be difficult territory, and one on which we never choose to embark. We must often handle it alone. With this large-scale or collective mourning, we trudge forward in cultural melancholy with the opportunity for a collaborative healing. We can make sense of loss and what it means for each of our past, current, and future selves. If social media makes a space to process this in a collective and social matter, than demonizing it is simply unhelpful to the process of grieving.

Contextualizing grief shaming allows us to also understand the ways in which hierarchies inhibit our human potential in our day-to-day life. There isnʼt much productivity that comes from telling other people that how they feel doesnʼt count or doesnʼt add up in some way, and wasting energy on this is a really poor way to cultivate community and healthy human interaction. Critical perspectives on grief in digital culture are worth exploring and making sense of, but shaming, in general, is only interested in making people feel bad.

Making sense of loss and mourning, in any way, is inherently productive. If we, as participants in mass culture and the making of our own nostalgia, are able to make any kind of connection or larger sense of grief, this is a positive opportunity for growth. Regardless of the platform used, it is imperative that there be room for mourning, whether it is for an intimate death or for the death of someone we did not actually know.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.