Cost of Living: Life Insurance and Burial in Black Chicago

Chicago, like many other diverse cities in the United States, has a complex history of race relations. With local and national policies, both legal and corporate, benefiting white citizens at the turn of the 20th century, the Black community was left to fend for themselves. From housing to life insurance, socio-political strategies purposely disenfranchised and undermined opportunities for success in the Black community, especially for elderly Black Americans who had worked hard their whole lives being paid less than their white counterparts. While an oppressive bureaucracy sought to keep Black Americans from thriving throughout their old age and even in death, the Black community innovated several work-arounds in order to circumvent those policies.

The end of the 19th century found Black Americans struggling to get ahead, despite the seemingly new-found sense of freedom of the post-slavery landscape. It was difficult to get by and to save money for old age, let alone leave something behind for your family after you were gone or cover the costs of a funeral. At the turn of the 20th century, 90% of Black Americans lived in the South.[1] The first wave of the Great Migration in 1916-1930 brought 1.6 million Black Americans from the rural south to northern cities. In places like Chicago, the Black community grew the fastest on the South and West sides, which offered new opportunities for the working class, but didn’t correlate specifically to improvements in housing, space, or health.

During this era, many Americans began to see an increase in burial costs for their loved ones. The professionalization of undertaking had a lot to do with shifts in technology and healthcare, as well as changing attitudes towards death in American culture. Despite a long history of funerary customs that centered on the home, the number of funeral parlors and mortuary services grew continuously. Many Americans saw these changes reflected in the rising cost of funerary expenses, which now included more ornate caskets, as well as the costs of embalming, securing a plot in a cemetery, floral arrangements, printed ephemera, and even photographs. Mourning families who chose to utilize a funeral home for the services must also have considered this cost in their funerary planning. These costs became prohibitive for those who had not saved for such an event, mainly lower-class Americans who struggled to make ends meet, even if they chose to forego an elaborate burial or service. The most basic of burial services was still out of reach.

Paying for life insurance allowed for individuals to pay a reasonable monthly premium that would pay out in the event of death so that the funeral cost would be covered; any leftover amount could be used by the family as they wished. This practice continues today. Life insurance first began in the United States in 1759, used by religious groups for the protection of women and children who faced the early death of the male head of household in Philadelphia.[2] The Presbyterian Synods founded the Corporation for Relief of Poor and Distressed Widows and Children of Presbyterian Ministers. This first life insurance group only served evangelical ministers. By the start of the 19th century, larger, non-religious life insurance companies were founded, such as the Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company, the New York Life Insurance Company, and the Baltimore Life Insurance Company.

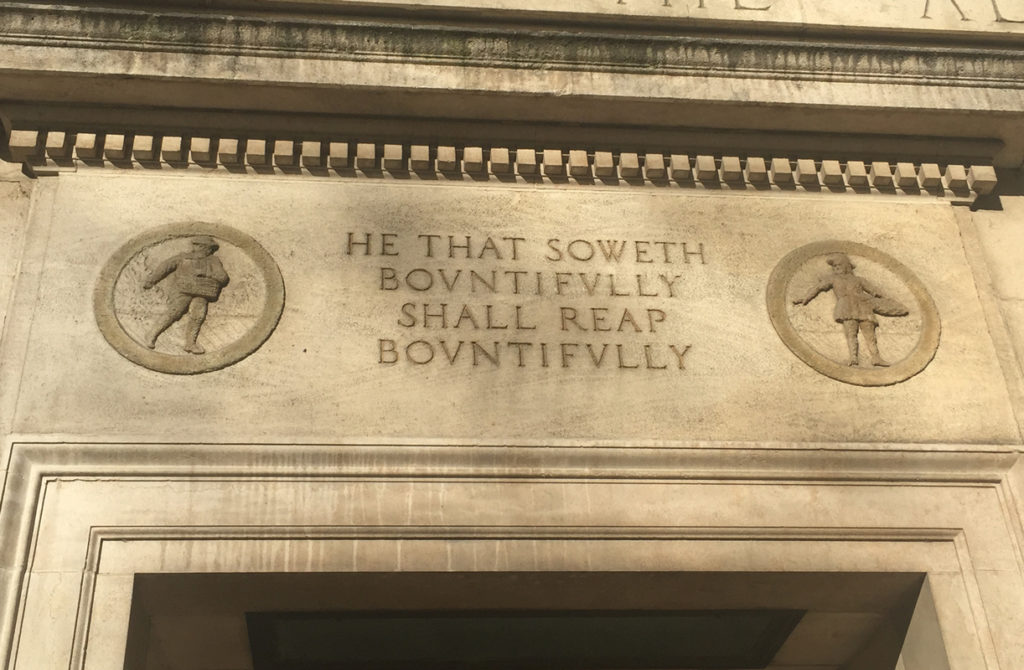

West-facing doorway of the Presbyterian Ministers Fund for Life Insurance (currently a Barnes and Noble). Image via Philadelphia Public Art.

Many life insurance companies failed after being in business for only a few years for various reasons: high rates, lack of standardization, and even the economic hesitance to place a financial evaluation on human life itself.[3] Americans hesitated to place a cost on human life at the start of the 19th century. By the 1840s, however, some state legislation changed how life insurance was run, and insurance companies invested in marketing their product more assertively. These new policies also changed who benefited from life insurance. For example, when New York State passed the Married Women’s Property Act of 1840, it allowed women to take out a life insurance policy on her husband, thus ensuring her financial security upon the event of his death, and protecting the payout of the premium from possible creditors after her deceased husband.[4] Prior to this, widows had little financial agency.

Mutual life insurance companies also weathered the financial Panic of 1837 better than privately held life insurance companies because mutual life insurance’s profits went to policy holders, rather than shareholders. This made for safer investments and a more structurally sound life insurance market. That said, life insurance in the 1840s was certainly not available to anyone that was enslaved.

After the Civil War, the life insurance market took off. Some life insurance companies said that military service voided any contract, while others offered to cover soldiers but with higher premium rates. For companies that paid out, their reputations saw lasting positive change. The life insurance market continued to flourish, but had limited legal regulation by state and federal government.

By the 1880s, Prudential Life Insurance of Newark put an end to the equal rates being offered to all, and increased rates for their Black beneficiaries. Historian Robert E. Weems writes, “Yet, in 1881, the Prudential Life Insurance Company of Newark cited an excessive Black mortality rate and established a rate structure where by Blacks paid higher premiums than whites for the same coverage. Other major insurance companies soon followed Prudential’s lead….”[5] As Weems points out here, the structural inequality built into the life insurance system ensured that the Black community would further be at a loss, even when burying their loved ones. By 1896, Prudential cut off all ties with Black beneficiaries and refused to offer them plans; they serviced white consumers only.[6]

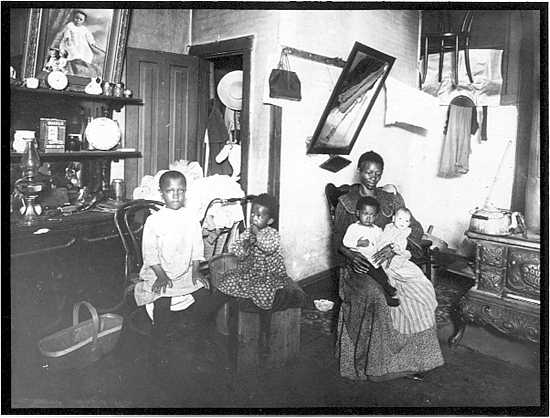

“Tenement living in Chicago, ca. 1900,” by Visiting Nurses Association. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society ( ICHi-21091) and via Illinois State Museum.

It’s hard to miss the irony of the higher rates for the “excessive Black mortality rate” considering that its cause is ultimately related to the same kind of structural inequality that raised life insurance rates: lynching and lack of safety, lack of access to healthcare, unsafe housing conditions, and extreme limitations on access to nearly all necessary services for a comfortable or sustainable life. Cultural theorist and theologian Emilie M. Townes writes about this in depth: “The 1920 death rate for Blacks was 48.4% higher than for Whites. By 1930, this had increased to 52.8%. Heart disease and TB, respectively, were the leading causes of death. Infant mortality rate were devastating, although national rates were dropping.”[7] In Chicago specifically, Robert Weems states that “a 1926 report by Chicago’s health commissioner glumly noted that Black Chicagoans’ death rate (22.5 per 1,000) closely resembled the rate in Bombay, India (25.4 per 1,000).”[8] The evidence of impoverishment among Black Americans was clear but little was being done to solve these large issues.

The “excessive Black mortality rate” also spoke greatly to the public health issues that many Black Americans faced. The Black mortality rate in Chicago, for instance, was exacerbated by housing issues. Living in dense city dwellings at the beginning of the 20th century meant that you were exposed to a variety of diseases (like the tuberculosis and heart disease cited above) with little access to preventative medicine. It was nearly impossible to escape an unsafe living situation when you were new to the city and trying to save money to move homes or even neighborhoods. With so many people coming to Chicago to find jobs or be closer to family traveling north, living in the city meant proximity to work but also to germs.

The Black community was also cut out of housing policies that would benefit many other working-class whites. These housing policies ensured that Black Americans continued to be offered tenement-style apartments, becoming renters for life in an unsafe building. For example, the Housing Act of 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which worked to keep families in their homes in lieu of foreclosure at the start of the Great Depression. While the FHA had admirable goals—to keep the cost of down payments affordable and to privately insure mortgages for those struggling to pay—these services only benefited those in certain regions. Ta-Nehesi Coates writes a thorough investigation of this practice, also known as redlining, in his remarkable essay “The Case For Reparations.” Coates writes:

The FHA had adopted a system of maps that rated neighborhoods according to their perceived stability. On the maps, green areas, rated “A,” indicated “in demand” neighborhoods that, as one appraiser put it, lacked “a single foreigner or Negro.” These neighborhoods were considered excellent prospects for insurance. Neighborhoods where black people lived were rated “D” and were usually considered ineligible for FHA backing. They were colored in red. Neither the percentage of black people living there nor their social class mattered. Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.[9]

It is clear that these policies comprise a systemic effort to ensure economic, cultural, and bodily failure to Black Americans. The mortgage industry followed the same pattern as the insurance industry: once one, singular agency or company took the lead in cutting Black Americans out of programs and policies, others in the industry followed suit.

Postcard showing the exterior of the Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company, 1954. Image via Illinois Digital Archives.

With housing, healthcare, and life insurance being managed by white companies and policy makers, the Black community had to find other means to address their needs. In many ways, this meant creating new opportunities from within their community. By the end of the 1930s, Chicago saw the creation of several Black-owned life insurance companies, including Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company (CMMAC), founded in 1925, as well as Leak & Sons Funeral Home, founded in 1933. Black-owned companies confronted two main issues in the Black community: intergenerational wealth and wellness, and respectful end-of-life options.

The CMMAC provided basic coverage for funerary expenses for Black Americans when it may have otherwise been unaffordable. The company also served as an opportunity for Black Chicagoans to enter the business world in a way that many white companies simply wouldn’t allow: this Black-owned company hired directly from their community and provided financial opportunities for success. Weathering the hardships that fell upon the entire country during the Great Depression in the early 1930s, the CMMAC had joined forces with the Metropolitan Funeral System Association (MFSA).[10] The MFSA connected all Black undertakers and funeral professionals across the city, uniting them through business but also creating a vast network of finances to pool together. Even in the toughest of times, the MFSA found ways to work with policy holders to lower premiums. The MFSA even accepted standard items such as butter in lieu of traditional financial payment.

Undertaker before funeral services. Southside, Chicago, Illinois. Image via Library of Congress.

The Black Chicago community also saw the arrival of a Black-owned funeral home, Leak & Sons. The company provided a much-needed service that that was affordable and respondent to the cultural demands of the community. Spencer Leak, current Vice President of Leak & Sons Funeral Home, represents the third generation of family ownership of this Chicago funeral home. He writes, “In 1933 my grandfather, Rev. A.R. Leak had a vision of opening his own funeral business after having realized that black people could not afford to bury their loved ones in a respectable manner.”[11] Still family-owned and serving the west side of Chicago, Leak & Sons Funeral Home saw the problem at hand and came up with a solution: respond to the need by providing the service.

The 1920s and 1930s were a time ripe for change for the Black community in Chicago. With the Great Migration underway, the need for a dynamic Black culture was crucial. Despite the many opportunities that Chicago provided to folks leaving the South, a few of its key issues were taken on by innovative Black businesses and community-driven initiatives.

[1] Thomas N. Maloney, “African Americans in the Twentieth Century,” in EH.Net Encyclopedia, ed. Robert Whaples. January 14, 2002. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/african-americans-in-the-twentieth-century/

[2] Dennis L. Peck, “Life Insurance As Social Exchange Mechanism.” in Handbook of Death and Dying, ed. Clifton D. Bryant (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003), 149.

[3] Viviana A. Rotman Zelizer, Morals and Markets: The Development of Life Insurance in the United States. (New York, NY: Columbia UP, 2017), xi.

[4] Mary L. Heen, “From Coverture to Contract: Engendering Insurance on Lives,” Yale Journal of Law & Feminism Vol 23, Issue 2 (2011): 339. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1322&context=yjlf

[5] Robert E. Weems, “The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company: A Profile of a Black-Owned

Enterprise,” Illinois Historical Journal 86, No. 1 (Spring,1993): 15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192684

[6] Robert E. Weems, “The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company: A Profile of a Black-Owned

Enterprise,” Illinois Historical Journal 86, No. 1 (Spring,1993): 16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192684

[7] Emilie M. Townes, Breaking the Fine Rain of Death: African American Health Issues and a Womanist Ethic of Care (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2006), 87.

[8] Robert E. Weems, “The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company: A Profile of a Black-Owned

Enterprise,” Illinois Historical Journal 86, No. 1 (Spring,1993): 17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192684

[9] Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

[10] Robert E. Weems, “The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company: A Profile of a Black-Owned

Enterprise,” Illinois Historical Journal 86, No. 1 (Spring,1993): 23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192684

[11] “About Us,” Leak & Sons Funeral Homes, http://www.leakandsonsfuneralhomes.com/about-us.html

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.