Wigs and Tories: The Shallow Brilliance of Colley Cibber

For those of you nostalgic enough to have shelled out money to see the recent Zoolander sequel, I present to you an image: Mugatu’s wig.

This wig is one of the greatest props in modern comedy. The bleached curls betoken vanity (it takes a lot of time and money to go platinum, trust me); the perfectly aligned middle part is that of one who has stylists to attend him at all times; the oddly placed puffs of hair mimic the unfathomable aesthetic sense of the high fashion world; and the curls on the forehead in the shape of an “M” are an instance of the obsessive branding that haunts our material culture. Plus, it looks incredibly silly.

As a historian of theatre, when I see a prop like this, I think, “where did that come from? Why do we as a culture enjoy silly wigs so much?”

Well, lucky for you and for me, I have an elaborate and surprisingly charming answer to that. It starts in 1696, when actor and playwright Colley Cibber first tread the boards of the Drury-Lane theatre as Sir Novelty Fashion, a character he had written for himself in his comedy Love’s Last Shift. Sir Novelty was a traditional “fop”: a mincing fancy man with a penchant for lace, silk, jeweled swords, snuff tobacco in mother-of-pearl boxes, and, most importantly, big expensive wigs.

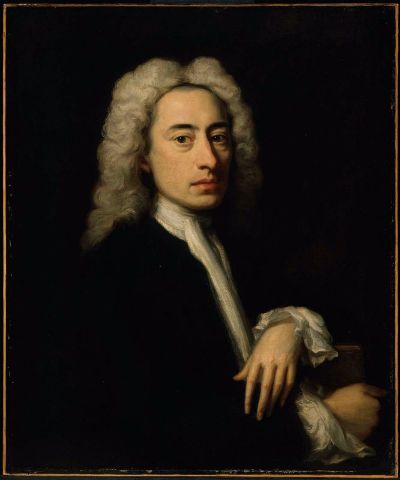

Colley Cibber, by and published by John Simon, after Giuseppe Grisoni, mezzotint, circa 1700-1725

At the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth, wigs were kind of a big deal. Theatre historian Joseph Roach[1] notes that a large, “full-bottomed periwig” (that is, a wig like the one pictured above, long, curled, with two peaks at the top) was the standard costume of the tragic actor. This was such a common trope that Joseph Addison, a dilettante satirist whose well-published wit stalked London’s elite, remarked wryly, “These superfluous Ornaments on the Head make a great Man.”[2]

Cibber certainly took this mocking maxim to heart, making a huge periwig the center of his iconically foppish character. Roach calls Sir Novelty Fashion’s headpiece “the most famously enlarged periwig of the Augustan age,”[3] and yet it wasn’t even the biggest Cibber wore. In The Relapse, sequel to Love’s Last Shift (and not written by Cibber), Sir Novelty, now created Lord Foppington, wears a wig so grandiose that it veils him altogether, for as he tells his wig-maker in the play, “a periwig to a man should be like a mask to a woman; nothing should be seen but his eyes.”[4] Basically, just imagine a very well-dressed Cousin It.

As I tell you Cibber’s story, I want you to keep that image present in your mind.

Colley Cibber was born to an English mother and a German immigrant father, the sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber.

Melancholy and Raving Madness, Caius Gabriel Cibber (1676). Placed at the entrance to Bethlem Hospital 1676-1815, now at Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

His family was respectably middle-class, and acting by that time had begun to become a somewhat respectable profession for an almost-erudite, sort-of-moneyed young man with a blithe wit and a talent for making himself look ridiculous. After a period of struggle and disappointment, Cibber eventually became a popular comic actor, no doubt with the help of his wig-maker, and started to lean in more toward his real-life roles as playwright and (eventual) theatre manager at Drury-Lane, one of the two London theatres that had a royal license to perform. Cibber wrote successful comic plays, a wildly popular adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III (which became the standard performance version of the play well into the nineteenth century), and a few original tragedies that flopped. Colley and his wife Katherine, an actress, had twelve children; their eldest boy Theophilus became a member and later manager of the Drury-Lane company mainly through nepotism, and their youngest girl, Charlotte, took up cross-dressing in order to labor to earn a living for her child (and eventually proposed marriage to a woman). The Cibbers did great things, but they were also a bit of a town laughing-stock.

If I were to ask you what sort of man I’ve just described, you probably wouldn’t say, “oh, definitely a Poet Laureate of England.” But that’s what you should say, because he definitely was.

You see, Colley Cibber was a flatterer. Possessed of a massive ego himself, he knew how to care for others’ egos. He was a people-pleaser, and therefore knew how to avoid offense. He was a pedant, and therefore knew exactly which classical allusions made for “good poetry.” He was the perfect softball nominee for the position of Professional Flatterer to an English King Who Doesn’t Speak English (that is, George II).

Here’s where the Tories come in. Think of them as hipsters, and Colley Cibber as a popular singer. He wasn’t a particularly talented poet, and he was a perennial sell-out; the Tories hadn’t even liked him before he was cool. Now that he was the hot ticket, however, they were on the war path, and none more so than poet and satirist Alexander Pope.

Alexander Pope, painting attributed to English painter Jonathan Richardson, c.1736

If you ask me, Pope had a chip on his shoulder. He was a small, disabled, socially awkward man, a Catholic in a time when that was the wrong thing to be, with an overwhelming fear of women and a wit too sharp to make him many friends (though the friends he did have were intensely loyal). He was, however, a talented poet (one of the few poets of that period to survive in classrooms to this day), and to see a stout, long-lived, people-pleasing mediocrity like Colley Cibber raise himself up in society was too much for the poor man to handle. I won’t say I don’t sympathize; I think we’ve all had that feeling at some point.

Pope began to attack Cibber frequently in his poetry, leading Cibber to publish a pamphlet in response, which led to an escalating print war. Things got especially frisky after Cibber published his autobiography, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber.

This is a wonderful book, in which a cheerfully aging Cibber looks back upon his life in the theatre, admiring his talented friends (one passage appreciating the actor Thomas Betterton is particularly famous), sharing his favorite jests, and poking gentle fun at his own vanity. In one of my favorite introspections of all time, Cibber writes, “I own myself incorrigible: I look upon my Follies as the best part of my Fortune, and am more concern’d to be a good Husband of Them, than of That; nor do I believe I shall ever be rhim’d out of them.”[5] The last part refers to the several satirical poets intent on improving society by mocking it, and who often made Cibber the butt of their jokes.

Despite Cibber’s protestations, Pope was determined to ‘rhyme him out’ of his vanity. To that end, he produced a great labor of spite: he re-published his satire of other poets, the Dunciad, re-written to be about Cibber, with an entire extra “book” added. This, unfortunately, is the main medium through which modern readers know Cibber’s name. The expanded and revised Dunciad included among its preliminary materials an essay titled “Ricardus Aristarchus of the Hero of the Poem.” Aristarchus, one of several guises in which Pope added footnotes and editorial comments to his own poem, sets up Cibber as embodying the three mock-heroic virtues of vanity, impudence, and debauchery. Which, to be fair, he did. Pope complains, “He [Cibber] is not ashamed (God forbid he ever should be ashamed!) of this Character; who deemeth, that not Reason but Risibility distinguisheth the human species from the brutal.”[6] Honestly, if you look at it that way, it’s all very post-modern.

I will admit that Pope effected some sick burns on Cibber in the Dunciad (there were a lot of jokes about erectile dysfunction), and Cibber’s theatrical career was for Pope an excellent source of derision. Cibber is represented as a devotee of the goddess Dullness, to whom he addresses this speech:

Dulness! Whose good old cause I yet defend,

With whom my Muse began, with whom shall end;

E’er since Sir Fopling’s Periwig was Praise,

To the last honours of the Butt and Bays…[7]

And there’s that damned wig again.

I love Lord Fopling’s periwig. Most of my fellow Cibber fans try to work around it; attempts to recuperate Cibber as a historical figure usually amount to defenses of his literary work and of his dignity. A prime example is from Leonard R.N. Ashley’s 1989 biography of Cibber, which ends thus:

Cibber deserves a better reputation than Pope’s Dunciad would give him. Though Pope immortalized him, he slandered him too. Cibber was anything but dull. He was no stupid mountebank, no forgotten figure of fun. He was a lot more than the drunkard and fornicator Edmund Bellchambers described when he edited Cibber’s Apology. Pope’s portrait and Bellchamber’s are false. It is better to look at Roubillac’s colored bust of Cibber in the National Gallery in London; to study the cheerful, shrewd, frank, and ruddy face, the humorous expression of the thin lips that seem about to speak, probably with a little vanity and with more than a little determination. There is the man whose best work is well worth attention, a man who occupies a small but significant niche in the edifice of English literature. Let Warburton pronounce his epitaph: “Cibber, with a great stock of levity, vanity, and affectation, had sense, and wit, and humour.”[8]

Colley Cibber, perhaps from the workshop of Sir Henry Cheere, 1st Bt, painted plaster bust, circa 1740

I find this defense moving, but in my opinion it misses some of the delight of Colley Cibber’s character. When Cibber died in 1757 (almost thirty years into his tenure as Poet Laureate), he certainly took with him some of the trappings of a grave, respectable figure. But that’s not who he was to begin with. He was the man whose shallow trappings brought audiences deep joy. He was the man who made a virtue of folly. Cast Charles II from his throne; Colley Cibber should go down in history as England’s greatest wig-wearer.

[1] Joseph Roach, It. U of Michigan Press, 2007.

[2]From The Spectator, qtd. in Roach, 130.

[3] Roach 135

[4] From Sir John Vanbrugh, The Relapse, qtd. in Roach 136.

[5] Cibber, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber, Comedian, chapter 1. (I used John Maurice Evans’ 1987 Garland edition, which unfortunately lacks sensible page numbers).

[6] Pope, The Dunciad in Four Books. I use John Butt’s 1963 Yale edition, wherein this passage can be found on p. 715.

[7] Pope, Dunciad in Four Books, 165-8 (p. 728 in Butt edition). “Butt and Bays” refers to the butt of sack and laurel crown that were the traditional symbols of the Poet Laureate.

[8] Ashley, Colley Cibber (Twayne Publishers, 1989), p. 135.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.