Death, Technology, and the “Return to Nature”

In the 1965 satirical movie The Loved One, Dennis Barlow is confronted with the extravagant kitsch of the funeral industry in Los Angeles. After the suicide of his uncle, the funeral operatives of Whispering Glades put him before a series of choices he is not ready to take: a lead-coated coffin, a Rest King coffin available in 8 colours, or an Emperor model? Should the coffin be waterproof, moisture proof, or dampness proof? Should the light on the tomb be “standard eternal” or “perpetual eternal” (the difference being that the first gleams only during the opening hours of the cemetery)? Should it be fuelled by propane or butane? By pretending to care about the individual wishes of Barlow’s uncle and of the bereaved, Mr. Starker of Whispering Glades succeeds in selling the most expensive coffin. With silk interiors, of course, because the deceased was a “sensitive” man.

In The Loved One, the funeral industry comes out as a fundamentally exploitative system, taking advantage of the emotional instability of the customers as well as of the deceased’s desires to be memorialized in a personalised manner. The book on which the movie is based was inspired by Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Death (1963). In this investigative report on the American funeral industry, the author unveiled how funeral operatives convinced the bereaved to pay for overly expensive services, persuading them that the amount they were willing to spend on the funeral was directly proportional to their love for the departed. This grim portrayal of the funeral industry, combined with the rise of environmental awareness characteristic of our time, is at the base of new approaches to both the disposal of dead bodies and the process of mourning. In this article I will describe three of these innovative solutions: The Urban Death Project, Capsula Mundi, and The Coeio Infinity Suit. Such initiatives, devised not by funeral practitioners but by designers and architects, claim to be at the head of a real cultural revolution in burial rituals, and I will expand on the kind of approach to death and death rituals that they are seeking to promote.

The last few years have seen a real explosion of alternative, ecological solutions for disposing of dead bodies without recurring to traditional funeral services. “Green funerals” and “natural burials,” for example, have become increasingly popular. These generally imply a rejection of cremation and embalming due to their polluting impact along with the burial of the body in a coffin or shroud made of biodegradable material. They often allow only for temporary, unobtrusive markers to memorialize the deceased in burial grounds.[1] Natural burial acquires an original twist in Capsula Mundi, a new form of burial currently being refined by Italian designers Citelli and Bretzel. The Capsula Mundi is an egg-shaped biodegradable container in which the deceased is laid to rest in a fetal position. Like a seed, the container is buried in the ground, and a tree chosen by the deceased-to-be is planted on top of it. While the tree does not have an inscription bearing the name of the individual, the location of the burial and the identity of the deceased can be located through a GPS system.

Capsula mundi photo via Treehugger

This new form of burial aims at favoring, and not hindering, decomposition. Indeed, decomposition is an integral part of its philosophy: the body was generated by Nature, and through the capsula it dissolves into nature once more.

Designer Jae Rhim Lee’s Infinity Burial Suit is a full-body suit worn by the deceased before burial. It contains a “biomix” of mushrooms and other microorganisms which, according to the website “do three things; aid in decomposition, work to neutralize toxins found in the body and transfer nutrients to plant life.” Thus, without a coffin and embalming chemicals, and aided by the biomix, the cadaver decomposes quickly, leaving no harmful traces on the environment.

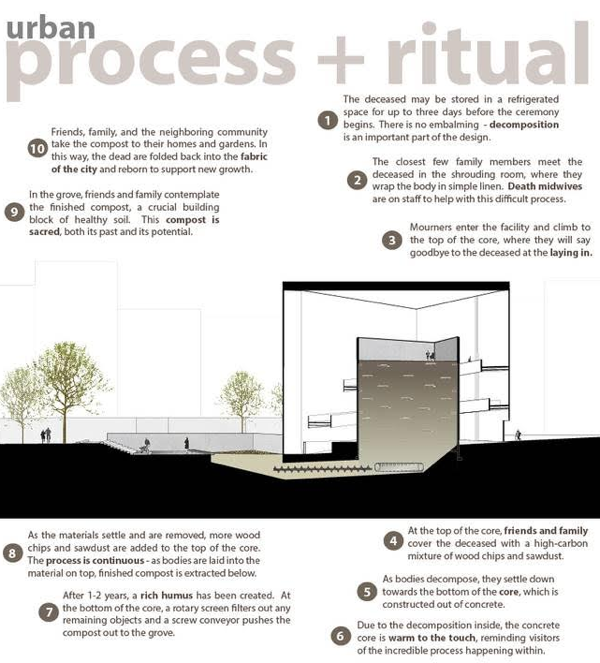

Decomposition, and the understanding of the dead body as something that can potentially nourish the environment, is at the core of architect Katrina Spade’s Urban Death Project (UDP). Through a process called “recomposition,” the aim of UDP is to transform dead bodies into soil, thus returning them to nature and to the collective. This is to occur not in natural burial grounds in rural areas, but in urban settlements, in tower-like structures as the one you can see in the picture.

Image via Treehugger

The ritual ideated around “recomposition” goes as follows: the dead body, wrapped in a shroud, is carried to the top of the structure, laid on the surface and covered with wooden chips. The body starts decomposing, and after a month it has transformed into soil, indistinguishable from the other bodies inside the tower. The relatives are then encouraged to bring some of the material home to their own gardens, and the remainder is used to nourish gardens both at the site and in the rest of the city. “In this way” the website reads, “the dead are folded back into the fabric of the city.”

These three projects are in different stages of development. While UDP is currently in a testing phase, Capsula Mundi is about to release on the market a smaller version of the ovoid container which can be used for ashes. The Infinity Burial Suit can already be purchased for $1500.

I am particularly interested in the discourse in which these innovations are presented, and upon which their importance is predicated. First of all, what immediately struck me about the way these initiatives are conveyed to the wider public was the aesthetic appearance of their websites. Gone are the weeping willows and the daffodils half blown away by the wind, the cornerstones of funeral graphics: these websites are designed fully embracing the minimalistic, cute warmth wildly deployed by marketing strategists of contemporary corporations. While Coeio’s website is certainly the most striking example, the rather infantilizing graphics of Urban Death Project’s explanatory video reach unsubtle paroxysms in equating natural decomposition to nourishing the planet (see the image below, with worms surrounded by beating hearts).

Funeral products: “super comfortable” “swag” at Coeio

Footage from the UDP video A Story of Life and Death

The fact that these websites are adopting the designs favoured by modern marketing (of a type described by the New York Times as “non-threatening, reassuring, playful, even child-like”) tells us that the projects not only speak the language of modern generations, but that they are also planned for a wide outreach, tapping into the lifestyle of a growing portion of the population, with its preference for organic products, healthy living, and its commitment to the respect of the environment. Anna Citelli, designer of Capsula Mundi, confirms this understanding of green burial as the ultimate lifestyle choice while explaining the ecological rationale of her innovative coffin: “This is a special cultural moment, one feels the need of acting for the care of the planet and for the future of new generations. A new awareness of the consequences of our choices goes through all the phases of our day, from food to clothing.”

Indeed, rather than just promoting products, Capsula Mundi, Coeio, and UDP openly promote a vision. Coeio talks about “a cultural shift,” specifying that “when someone engages with our products, they are also engaging in a movement, and become like family to us.” Likewise, the designers of Capsula Mundi define it as “a cultural proposal,”[2] and UPD talks about a real “Death-care revolution” and the creation of “a culture of giving” through their method of recomposition. The vision promoted by the projects is a mix of death-awareness and eco-friendly thinking, a reinvention of death rituals which is at once environmentally sustainable and meaningful. In fact, the three initiatives go to great lengths to stress that their visions are meaningful, that they are not merely a utilitarian solution to the need of finding less-polluting and space-consuming alternatives to traditional burial practices (simply look at the image of the recomposition tower above, where “recomposition” is presented as both a “process” and a “ritual”).

In these new, secular rituals, meaning is found through a different narrative. At a conference session on death in literature in Harvard, I once asked a speaker whether, considering the collapse of former cosmologies we used to think about death, we still need a narrative to talk about our unavoidable demise, of telling ourselves a story to make sense of it. The answer I was given was a resolute yes. By appealing to a sense of shared responsibility, of mutual care and nourishing, these innovations propose a narrative of return to nature (and the phrase recurs innumerable times in the internet content dedicated to “green” and “natural” burial). Thus, the forest emerging from the seeds of Capsula Mundi is not just a wood but a “sacred forest,” the soil produced from stacking corpses in towers full of woodchips is “beautiful” and “sacred”[3] and the mushroom suit allows us to “share our journey” with Coeio.

One of the philosophical underpinnings of this narrative is that Western society is increasingly removed from nature, and that the way in which deaths have been dealt with in the last century is, too, un-natural. Chemical treatment of the body through embalming (thus denying the obvious fact that a dead body is doomed to decay), the medicalisation of death, and the fact that care for the dead is taken over by external parties are all seen as evidence of this distancing, and are pointed to as causes of the denial of death which supposedly characterizes our society. The shift is seen by many advocates of the solutions described in this article as being fundamentally unhealthy, transforming death in a profoundly traumatic experience. Caitlin Doughty, founder of the Order of the Good Death and owner of a green funeral home, states it boldly: “death itself is natural, but the death anxiety and terror of modern culture are not” (my emphases).

The narrative of the return to nature advanced by the proponents of the solutions above appear to me as a combination of two extremely pervasive conceptions in Western thought. The first is a Romanticized version of the opposition between nature and culture, where nature is perceived as a condition of primordial harmony and culture as a man-made influence disrupting natural order. The second is, instead, is the biblical narrative of fall: by exiting the natural order, humans lose their innocence, and their entrance in the cultural world is characterised by a traumatic sense of loss. Understood through the lens of Romantic philosophy, the taboo of death that characterizes our society is the consequence of the medicalization and the commercialization of death, two “unnatural” practices. In Anna Citelli’s words: “Making death taboo is part of the diffused thinking that human beings are outside nature […] Or–worse–over it.”

While I consider the attempt to make burial more environmentally sustainable as praiseworthy, I remain skeptical about the “philosophical” premises of this death-care revolution, especially in the understanding of what constitutes a “natural” way to die. That death is natural, but that the anxiety and terror surrounding it are not, is a bold statement and a historically questionable one, and I will devote my attention to it in the next article.

[1] The Good Funeral Guide http://www.goodfuneralguide.co.uk/find-a-funeral-director/what-is-a-green-funeral/

[2] http://www.capsulamundi.it/it/ Translated from Italian “una proposta culturale”

[3] http://www.urbandeathproject.org/ (points 6 and 7 in the slideshow)

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.