General Access: Hair Jewelry and Godey’s Lady’s Book

The sentimental culture that flourished in the 19th century represents a particular elevation of platonic relationships, in which boundaries were blurred between friends and public displays of affection were not only tolerated, but encouraged. In the 21st century, it would be odd to collect my hair, weave it into the face of a brooch, and bestow it as a meaningful gift to a close friend. The Victorian era, however, celebrates a kind of skilled craft in which our own bodily remnants could be shared and celebrated openly. The history of hair jewelry, ornaments made by manipulating human hair, exemplifies the way in which sentimental culture has shifted over time.

Hair pendant, early 19th century (via Art of Mourning)

At the apex of Victorian culture in the early to mid 19th century, American culture flourished with a particular brand of emotional exuberance that honored the feminine, domestic craftsmanship of hair jewelry. This social landscape validated and supported practices and objects that were intrinsically connected to the domestic sphere, and highlighted the supposed tenderness of womanhood. Hair jewelry could be closely tied to memory because of its intimate embodiment of the current or former beholder: hair had been a part of someone. While that sentiment has certainly changed in recent years, the history of hair jewelry is both long and generally endearing.

Hair brooch with inscriptions “Julia” and “Died April 22. 1864.”, 1864. Collection of Historic New England.

The first hair jewelry is thought to date as far back as the 9th century, which included a possible trimming of hair from the Virgin Mary; many holy reliquaries were rumored to include small wisps of hair from various saints.[1] The presence of hair secured a special kind of luck for the wearer, ensuring that the previous owner of said hair watched out for them. Wearing these kinds of pieces also connected the living to the dead in a very concrete way.

Hair jewelry hit its period of utmost popularity during the early to mid 19th century in Europe and the United States. Victorian mourning culture hit its highest peak in the winter of 1861, when Queen Victoria stylishly embraced her mourning ritual at the passing of her husband, Prince Albert. All of England, and eventually the United States, took notice of her deliberate aesthetic and performative choices. Not only was she dressed in all black, but she often donned a locket honoring her late husband:

A small gold memorial locket, set with central oval onyx, black on white, with diamond star set in plain gold border with blue enamel inscription, “Die reine Seele schwingt sich auf zu Gott”, roughly translated as ‘The pure soul flies up above to the Lord’. Opens to reveal hair on one side and photograph of Prince Albert on the other, both under glass.”[2]

Interior view of Queen Victoria’s locket (via Royal Collection)

The piece remains as an object in the Royal Collection trust, which is held in trust by the Queen of England and seeks to preserve items crucial to the enduring legacy of English royalty. Prince Albert’s hair is carefully secured behind a small piece of glass, safeguarded to endure throughout time.

Queen Victoria’s locket also includes a photograph. Historically, jewelry emblazoned with a painting of a loved one, either dead or alive, was an accessory of only the wealthy, but photography made likenesses relatively cheap and widely available. In the instance of loss, the photograph may be either a memorial with an image of the living or a postmortem photograph. (It is rumored that Queen Victoria slept with a postmortem photography of her husband.)[3] Geoffrey Batchen, scholar of sentimental portraits and objects, writes: “A photograph incorporated into a piece of jewelry is put literally in motion-twisting, turning, and bouncing, sharing the folds, volumes and movements of the wearer and his or her apparel. No longer in isolation, the photograph becomes an extension of the wearer…”[4] This small, intimate gesture of commemoration to love and loss is an example of how the worn object is intentionally close to the body. This kind of proximity brings the memorial close to one’s heart, giving loss a literal materiality. Queen Victoria, and other widows, must have felt a sense of comfort after Albert’s early death, knowing that the likeness of her most beloved remained so close to her.

Mourning has traditionally fallen within the realm of the feminine, as it is both an emotional affair and deals with the body. Mourning is also understood as a performance, one that is often connected more closely with women because of their social roles in the 19th century. As Victorian culture amplified and solidified its ideal ways of mourning, middle and upper class women were also expected to perform in line with mass culture. In these times, women may have needed a bit of guidance.

Image of Godey’s Lady’s Book, from The Art of Hair Work: Hair Braiding and Jewelry of Sentiment

Godey’s Lady’s Book was founded by Louis Antoine Godey as a publication to inform, entertain, and educate the American woman. Godey was born to two poor French immigrant parents and had no formal education as a child. He came of age working for publications in New York, and then in Philadelphia. He eventually released the first Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1830 as a collection of French articles and images of women’s fashion. The social appreciation of French culture and its exquisite tastes spoke to women in the eastern United States, and its subscription base grew quickly over the next decade. By the 1840s, Godey’s Lady’s Book had the highest circulation of any publication in the United States.[5]

Godey especially found success in this publication after he hired Sara Josepha Hale in 1837. Hale was a poet and writer, and was working as an editor for a rival publication, Ladies Magazine and Literary Gazette. She is often remembered for penning “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and played a crucial role in the formalizing of the Thanksgiving holiday. Aside from that, Sara Josepha Hale was a radical suffragette who used Godey’s Lady’s Book as a place to pen essays on the importance of formalized, advanced education for women. She also published the works of emerging writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Hale’s candid approach to the role of women in American society was evidently noticed and appreciated, given the increase in circulation of Godey’s after she became editor.

Godey’s Lady’s Book, with its essays and fashion plates, was considered the go-to for feminine etiquette and style. The book published a wide assortment of advertisements for dressmakers, handicrafts, and popular home goods. By the middle of the century, hair jewelry had made its way to Godey’s and women were introduced to hair jewelry as both a craft and a product. Godey’s Lady’s Book brought hair jewelry to the masses.

While hair culture was often about mourning, it wasn’t only relegated to the realm of loss and despair. Hair jewelry became a popular, modish approach to fashion. It adorned braided bracelets, inlays on rings, intricate woven tubes hanging from earrings, and delicate swoops across golden brooches. Hair became a celebrated medium of craft. The middle class American woman did not have to invest in precious gemstones to create exquisite jewelry, but could collect her own hair and the hair of her loved ones as a means of expression, appreciation, and culture.

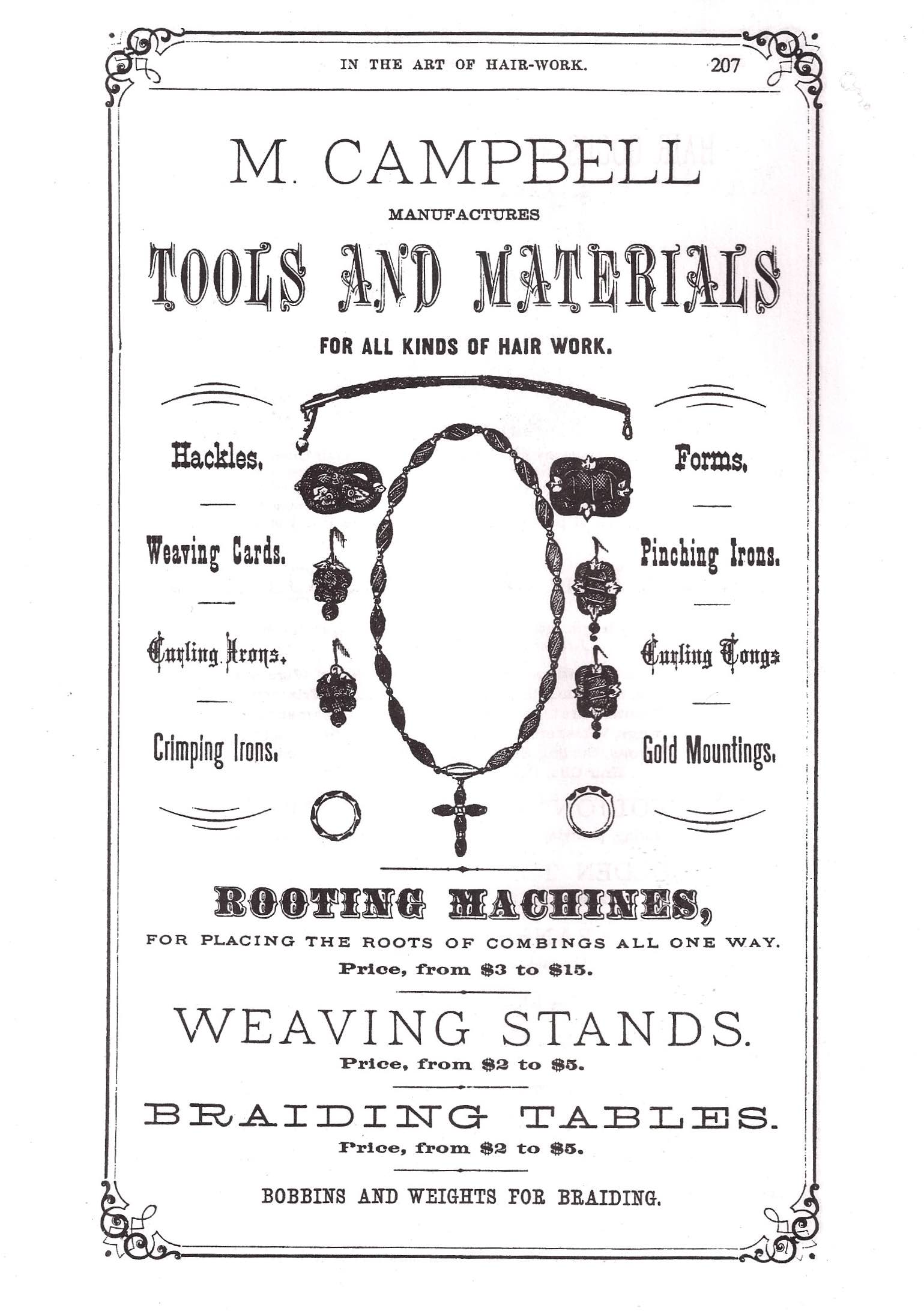

Godey’s Lady’s Book not only sold the “tools and materials for all kinds of hairwork,”[6] but it also sold pre-made items to to supplement fashionable collections for women who could did not practice the highly intricate craft of hairwork. Godey’s Lady’s Book formalized hair work as a craft, but also as a commodity, removing the time, energy, and delicate hand that it took to create these beautiful adornments.

Advertisement in Godey’s Lady’s Book, from The Art of Hair Work: Hair Braiding and the Jewelry of Sentiment

The selling of sentimental objects, or even part of the body such as human hair, is a complex negotiation. The reality of a capitalist, material-based culture reconsiders emotion and memory as a potential for product. The lucrative market for products intrinsically connected to the feminine sphere, connected to the body, and affectively represented, demonstrates the crucial and growing economic power for Victorian women. Geoffrey Batchen writes, “Indeed, memory is one of those abstractions increasingly reified in the nineteenth century, used to enhance the commercial value of such objects of exchange as keepsakes….”[7] But he may leave out the radical change that this commercial value pointed to: women’s work and women’s interest not only mattered, they had financial worth.

Godey’s Lady’s Book made a lasting impact on American culture. It was one of the first publications to include high quality images, which allowed for its readers become visually literate in a way that many women historically had not been. Today, many museums hold Godey’s in their collections because of its cultural legacy and impressive images. After six decades of successful publication, Godey’s Lady’s Book came to an end in 1896. It was renamed Godey’s Lady’s Magazine during the last several years and was eventually absorbed by The Puritan, “a journal for gentlewomen.”[8]

While Godey’s Lady’s Book certainly brought hair jewelry to the masses, the publication played a wider role in introducing education and culture to thousands of American women. Often brushed off as a basic fashion magazine, Godey’s pushed against mainstream publication expectations that women ought to abide by particular social norms. While hair jewelry may not be understood as a radical craft or object, hair jewelry inevitably commodified women’s handicraft, brought it to the mainstream, and popularized feminized, sentimental culture.

[1] Deborah Lutz. Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015). 131.

[2] Royal Collection Trust Collection Database. “RCIN 65301” https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/65301/queen-victorias-locket, Royal Collection Trust. Online. Accessed August 24, 2016.

[3] Ellie Cawthorne. “7 things you (probably) didn’t know about Queen Victoria.” History Extra, BBC History Magazine. August 26, 2016. Accessed August 27, 2016. http://www.historyextra.com/article/era/7-facts-you-probably-didn%E2%80%99t-know-about-queen-victoria

[4] Geoffrey Batchen. Forget Me Not: Photography & Remembrance (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004), 95.

[5] “Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1830-1898.” Cleveland Museum of Art. 2012. Accessed August 21, 2016. https://www.clevelandart.org/research/in-the-library/collection-in-focus/godeys-ladys-book-1830-1898

[6] Jules and Kaethe Kliot, eds. Art of Hair Work: Hair Braiding and Jewelry of Sentiment (Berkeley: Lacis, 1996), 207.

[7] Geoffrey Batchen. Forget Me Not: Photography & Remembrance (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004), 95.

[8] “The Puritan Archives.” The Online Book Page. Accessed August 24, 2016. http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=thepuritan.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.