Treasonous Transmissions and the Death of Clue‘s Singing Telegram Girl

Three telegraphy scenes:

− The Supreme Court, Washington, D.C., May 24, 1844: At the choosing of Annie Ellsworth, Samuel B. Morse sent the message “What hath God wrought?” to Alfred Vail in Baltimore.

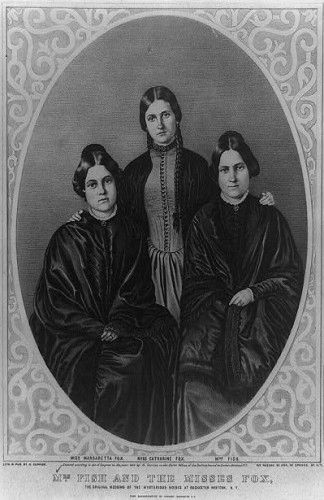

− The Fox Family Home, Hydesville, NY, March 31, 1848: Daughters Kate and Margaretta and their mother Margaret of the Fox family communicate with the spirits inhabiting their home through a series of claps and rappings.

− A Mansion, New England, 1954: It’s dark. The doorbell rings. Eyes peer out of the darkness, terrified. The door opens. A woman and a voice. “Dadaddadadada! I am your singing telegram!” A gunshot is fired and she falls to the ground. The Singing Telegram Girl has been shot. The door slams shut.

These scenes are dramatizations of the history of telegraphic communication, which, in the first scene, begins with the transmission of a statement from chapter 23 of the Book of Numbers, the fourth book of the Hebrew Bible. This book tells the story of God’s handing down of the laws and the Israelites’ journey to the Promised Land. This is an immaterial divine transmission and a physical transmission from one place to the next.

The second scene sparked America’s avid enthusiasm for contacting the dead and the Modern Spiritualist movement. The “spiritual telegraph” was channeled through the medium, a female body.

This third scene occurs towards the end of the 1985 now-cult classic movie Clue starring Tim Curry, Eileen Brennan, Madeline Kahn, Christopher Lloyd, Michael McKean, Martin Mull, and Lesley Ann Warren. Based on a board game, the movie brings paper characters to life. What interests me about this movie is the curious appearance of the Singing Telegram Girl, her tragic ending, and the complicated analysis which it affords. Not only does this scene evoke the nineteenth century spiritualist telegraph, but in conjunction with its historical setting, the McCarthy era, it calls forth other moments in American history (including the Salem Witch Trials). The Singing Telegram Girl’s body, carrying the message from a distant source unknown, was sacrificed. Or, was she punished for treason? In her appearance and demise, feminine desire, the longing and failure to communicate, and political censorship interweave.

This reading of Clue, a movie that had originally flopped at the box office, may appear obscure. However, the ways in which politics, media, desire, and electricity assemble as driving forces of the movie are potent.

Ethereal Connectivity

Samuel B. Morse sent the first official telegraph on May 24, 1844: “What hath God wrought?” On March 31, 1848, the Fox family communicated with the ghosts inhabiting their home through a series of knocks. Both of these methods of distant communication take the form of a series of taps that are translated by someone versed in that language; the electromagnetic telegraph meets the spiritualist telegraph. In the case of the electrical and later wireless telegraph, the technician holds the key to the message’s translation. For the spiritualist telegraph, the body of the medium, usually a woman and in the case of the Fox’s, two sisters, is the channel that connects the distant realms of the living to the dead.

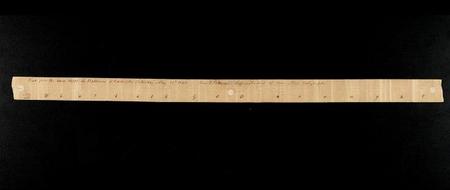

Message sent by Alfred Vail and transcribed by Samuel Morse using the electromagnetic telegraph on May 24, 1844, Artifact, National Museum of American History, EM*001028.

In Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, Jeffrey Sconce compares the two telegraphs:

In contrast to Morse’s material technology of metal, magnets, and wire, the spiritual telegraph could only exist in the mortal world as a fantasy of telegraphic possibility. In an era when the technology of the telegraph physically linked states and nations, the concept of telegraphy made possible a fantastic splitting of mind and body in the cultural imagination, demonstrating that electronic presence, whether imagined at the dawn of the telegraphic age or at the threshold of virtual reality, has always been more a cultural fantasy than a technological property.”1

At first, this telegraphic communication with the dead existed in immaterial forms, either only audible signals or light waves in photographs. However, mediums later began to manifest a material substance during séances, ectoplasm, which would emanate from the orifices of their bodies. This was a physical sign of the spirit with whom they were in contact becoming flesh.

Franz Anton Mesmer’s concept of “fluid” was used to describe the workings of his method of “animal magnetism,” (from anima, Latin for spirit) which would later be called hypnotism. John Durham Peters, in his book Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication, characterizes this fluid as what enabled Mesmer and others to generate a “unified field theory of the material and moral forces” of the world because it “coursed from person to person and from humans to cosmos, acting, like magnetism, at a distance”.2 The notion that a fluid-like substance connected and filled the voids of matter is not new. For ancients, “[i]t is that vitalistic principle which holds the whole together.”3 For moderns, it described the workings of electricity and radio. For us contemporaries, ether signifies the ethereal, the celestial. Towards the end of Clue, the lights go out; electricity ceases to illuminate. Each of the guests finds themselves alone in the dark. This is when the Singing Telegram Girl meets her demise. The shadow of secrecy is violent in this house.

Heretical Messages

After the American Civil War, Spiritualism rose in popularity. As Harriet Beecher Stowe writes in her essay “Modern Spiritualism,” featured in her 1886 book The Salem Witchcraft, The Planchette Mystery, and Modern Spiritualism with Dr. Doddridge’s Dream:

Our own country has just been plowed and seamed by a cruel war. The bullet that has pierced thousands of faithful breasts has cut the nerve of life and hope in thousands of homes. What yearning toward the invisible state, what agonized longings must have gone up as the sound of mournful surges, during these years succeeding the war! Can we wonder that any form of religion, or of superstition, which professes in the least to mitigate the anguish of that cruel separation, and to break that dreadful silence by any voice or token, has hundreds of thousands of disciples? If on review of the spiritualistic papers and pamphlets we find them full of vague wanderings and wild and purposeless flights of fancy, can we help pitying that craving of the human soul which all this represents and so imperfectly supplies?4

She argues that people turn to Spiritualism because they have lost faith and are starving: “the human soul, in a state of starvation for one of its normal and most necessary articles of food, devours right and left every marvel of modern spiritualism, however crude.”5 Further, she states that those who take-up Spiritualism will “[i]nstead of angels, whose countenance is as the lightning, they will have ghosts and tippings and tappings and rappings. Instead of the great beneficent miracles recording in Scripture, they will have senseless clatterings of furniture and breaking of crockery.”6

In this book, the essays on Modern Spiritualism and witchcraft in Salem are paired. The Salem Witch Trials marked a devastating moment for women’s bodies and desires. Deemed heretics, these women were destroyed. With the “separation” of the church and state, supposedly heretical behaviors are transferred into the rhetoric of treason. With the Red Scare, traitors weren’t seduced by the devil, rather, it was communism that had taken them over. And, it should not be forgotten that after the murder of the Singing Telegram Girl, it is revealed that Professor Plum, a psychiatrist who lost his medical license, had had an affair with her; she was one of his patients. The very patient that caused him to lose his license.

Taking place during the McCarthy era, Clue is all secrets and consists of discreet communications. The reason that the characters gathered in the New England mansion is because their blackmailer had invited them. Upon arrival to the house, each of the guests is called by a pseudonym; no one, other than the blackmailer, is supposed to know their real names. Their identities are kept confidential. Each is estranged from the other. As Mrs. Peacock, one of the characters, points out when she attempts to initiate conversation over dinner: what are they to talk about if they can’t know anything about each other? The only informational communication allowed in this system is the blackmailer’s note.

S. O. S.

In closing, another scene – a conflation of federal and spiritual communications:

At the end of the movie, an evangelical going door-to-door proselytizing the Word rings the doorbell. He holds a pamphlet bearing the question “Do you believe in Jesus?” As it turns out, he is an FBI officer coming to intervene and save the day.

The characters are trapped in the house, unable to communicate with the outside world. Telegrams, phone calls, listening to the radio, and watching TV all promise death (the stranded motorist and police officer were both killed after using the telephone, Yvette the maid (who had listened to the radio) was strangled, the Cook (who had been watching TV while preparing dinner) ended up with a knife in her back). Any sort of contact from a distance ends in the loss of life.

The telephone wasn’t able to help them. Neither could letters or telegrams. Can only a divine presence save the guests? Save us all from ourselves?

1Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 27.

2John Durham Peters, Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 90.

3Joe Milutis, Ether: The Nothing that Connects Everything (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiv.

4Harriet Beecher Stowe, The Salem Witchcraft, The Planchette Mystery, and Modern Spiritualism with Dr. Doddridge’s Dream (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1886), reprints from The Phrenological Journal, 107-8. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/salemwitchcraftp00stow

5ibid. 111

6ibid.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.