Re-Enacting Whiteness

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865. In the days that followed his death, the country deeply mourned their leader. He died only six days after the South surrendered in the Civil War, and he barely had time to prepare the United States for what would come next. Lincoln was the first president to be embalmed; his body traveled on a train from Washington D.C. through the Northeast and headed to his home of Springfield, Illinois, where he would be laid to rest. Lincoln’s funeral train arrived in Springfield on May 3, and he was finally buried on May 4, 1865.

After 150 years, Lincoln is still being mourned. On May 2, 2015, a re-creation of Lincoln’s funeral car arrived in Springfield alongside the thousands of people who flooded the Illinois capitol to catch a glance of it. Inside of the train lay a coffin, replicated from the one that Abraham Lincoln was buried in. I cannot find out what lay inside the re-created coffin; I can only hope that it was some kind of contemporary Lincoln effigy, lovingly handcrafted for this very occasion.

Both excited and self-conscious about my decision to attend this patriotic performance, I grappled with making sense of my surroundings. Looking out at the throngs of people wearing Lincoln-themed T-shirts who were commingling with the re-enactors, I couldn’t quite place myself. This event takes place in two different realms: the world of American history enthusiasts (to which I, somewhat embarrassingly, belong) and some kind of conservative political universe (where I definitely do not belong). I couldn’t quite figure out if I was there for pleasure or research, and I certainly didn’t fit in with the sea of aggressive Lincoln appreciators.

Both excited and self-conscious about my decision to attend this patriotic performance, I grappled with making sense of my surroundings. Looking out at the throngs of people wearing Lincoln-themed T-shirts who were commingling with the re-enactors, I couldn’t quite place myself. This event takes place in two different realms: the world of American history enthusiasts (to which I, somewhat embarrassingly, belong) and some kind of conservative political universe (where I definitely do not belong). I couldn’t quite figure out if I was there for pleasure or research, and I certainly didn’t fit in with the sea of aggressive Lincoln appreciators.

I did, however, notice that the crowds were nearly all white. From the diehard re- enactors who donned widowʼs weeds, elaborate mourning garb, Lincoln arm bands, or Union uniforms, to the more casual Lincoln fan who sported a fashionable top hat, they were all white. Springfield is 75.8% white and 18.5% black.1 The throngs of Lincoln lovers did not represent Springfield but rather embodied whiteness, in the way that history itself is constructed as a starched and simplistic linear narrative.

It goes without saying that history is whitewashed. The stories that are legitimized, reproduced, and reanimated are the stories of white bodies, in white communities, with specifically white agendas. The Civil War is just this. American history, in a traditional academic sense, exists not to inform and shape contemporary minds, but rather to reinforce systems of oppression. Journalist and writer Ta-Nehisi Coates may have said it best in his piece “Why Do So Few Blacks Study the Civil War?” where he points to just this: “For that particular community, for my community, the message has long been clear: the Civil War is a story for white people—acted out by white people, on white people’s terms—in which blacks feature strictly as stock characters and props.” 2

In the many events and speeches that followed the funeral procession, the performances and talks surrounding Lincoln were explicitly not connected to the immense sociopolitical change which came out of Lincoln’s term as president, and which has consequently shaped the cultural landscape of the United States. There was no mention of the Emancipation Proclamation. No one talked about how slavery was abolished under Lincoln, or how the Union army included black soldiers who fought and died with honor while defending a country which so passionately limited their every action. There were no black women in mourning, no black men in the long processionals. Lastly, there was no tie to current events in the United States, such as the riots in Baltimore or the wider wave of protest against institutionalized violence on black men, both of which are directly related to the historical atmosphere to which this funeral is so closely tied.

The programming for the 2015 Lincoln Funeral re-enactment covered a breadth of white historical subjects. Just north of the city of Springfield in the small town of Princeton, the Daughters of the American Revolution hosted a diary readings that documented the first hand account of Civil War nurses and their experience on the battlefield. Mrs. Sarah Gregg was white.

The commemorative opening ceremony began after the end of the procession. The various speakers for this discussed liberty and freedom in both the 1860s and the 2010s. Speakers discussed Lincolnʼs life and relationships and his political genius, as well as the direct impact that Lincoln had on the community of Springfield. The speakers, however, failed to mention civil rights, or slavery (as an institutional injustice or as an historical American tradition). The ceremony itself was located just outside of the Old State Capitol in Illinois. This building is the site where both Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama announced their intentions to run for president, in 1858 and 2007, spanning nearly 150 years of troubling American politics.

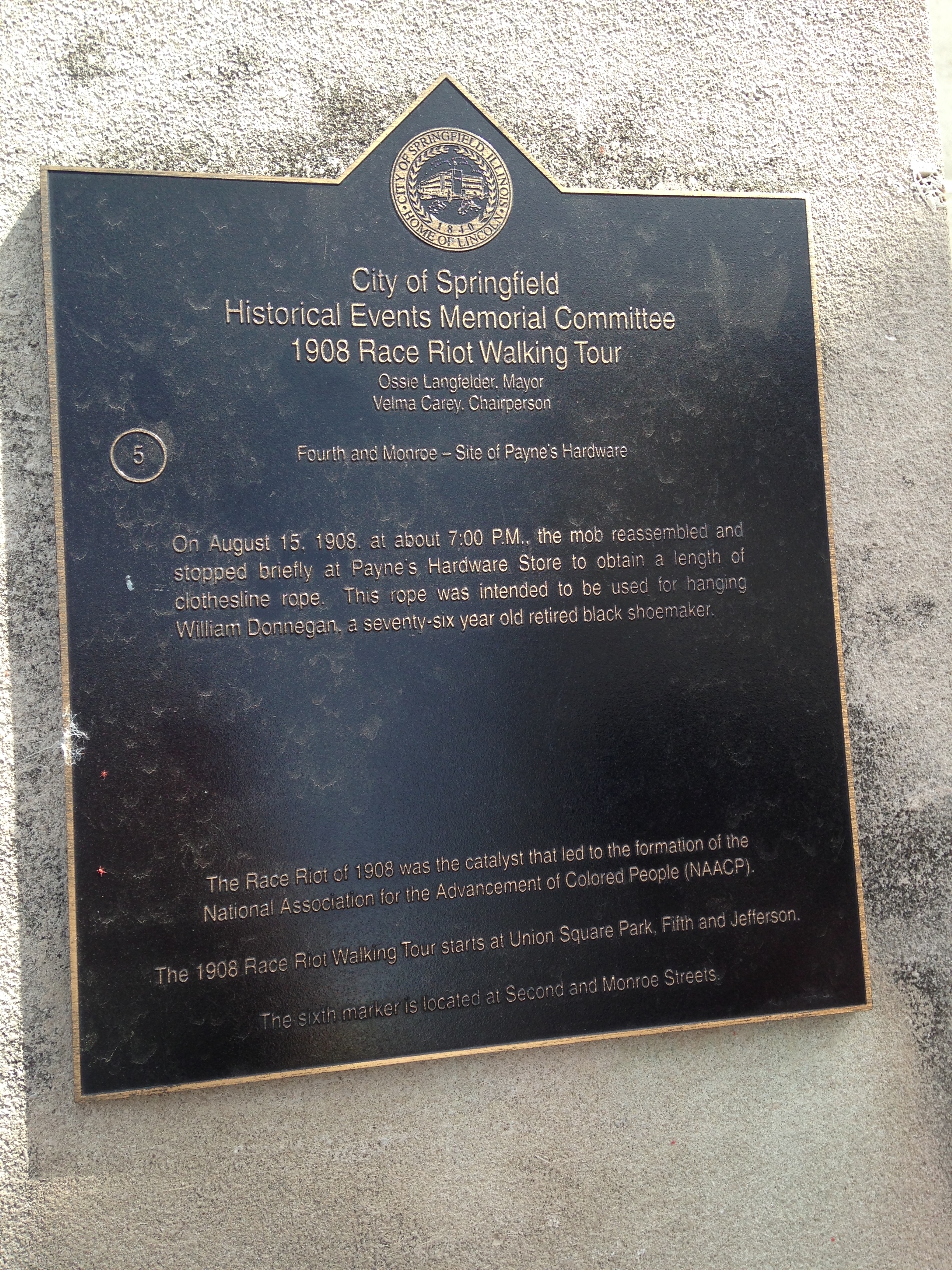

The city of Springfield itself was largely devoid of markers of discussions of race, despite the omnipresence of historical markers and informative signage. In my short time there, I was able to find two distinct markers of race being discussed. I found the first while I was walking around downtown Springfield. It was a small sign marking the Springfield race riots of 1908, which were “the catalyst that led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).”

This riot was formed by white Springfielders who joined together in response to a white woman who had been assaulted, in her home, by a black man. Shortly after this incident, word spread that another white woman had also been assaulted, in her home by a black man. Two black men were taken into custody by the Springfield police, and the mob moved to the courthouse where they demanded that the men being held be turned over to the mob. Unable to gain access to the two suspects, the mob found two other black men in the community and lynched them instead. The riots only continued from there; the white rioters of Springfield burned and destroyed the homes of black families and looted businesses that were run by or supported the black community of Springfield. The stores and homes of white families were left untouched. By the end of this tragic event, six black men had been shot, two black men were lynched, and the local economy had been decimated. Two thousand black Springfielders were run out of town.

This riot was formed by white Springfielders who joined together in response to a white woman who had been assaulted, in her home, by a black man. Shortly after this incident, word spread that another white woman had also been assaulted, in her home by a black man. Two black men were taken into custody by the Springfield police, and the mob moved to the courthouse where they demanded that the men being held be turned over to the mob. Unable to gain access to the two suspects, the mob found two other black men in the community and lynched them instead. The riots only continued from there; the white rioters of Springfield burned and destroyed the homes of black families and looted businesses that were run by or supported the black community of Springfield. The stores and homes of white families were left untouched. By the end of this tragic event, six black men had been shot, two black men were lynched, and the local economy had been decimated. Two thousand black Springfielders were run out of town.

The riots were a wildly important event, but the only thing that I was able to find in my time in the city that actually mentioned race, whether it be contemporary or historical, was a small street side sign. The sign is part of a city walking tour, but was never mentioned in any of the goings-on that weekend.

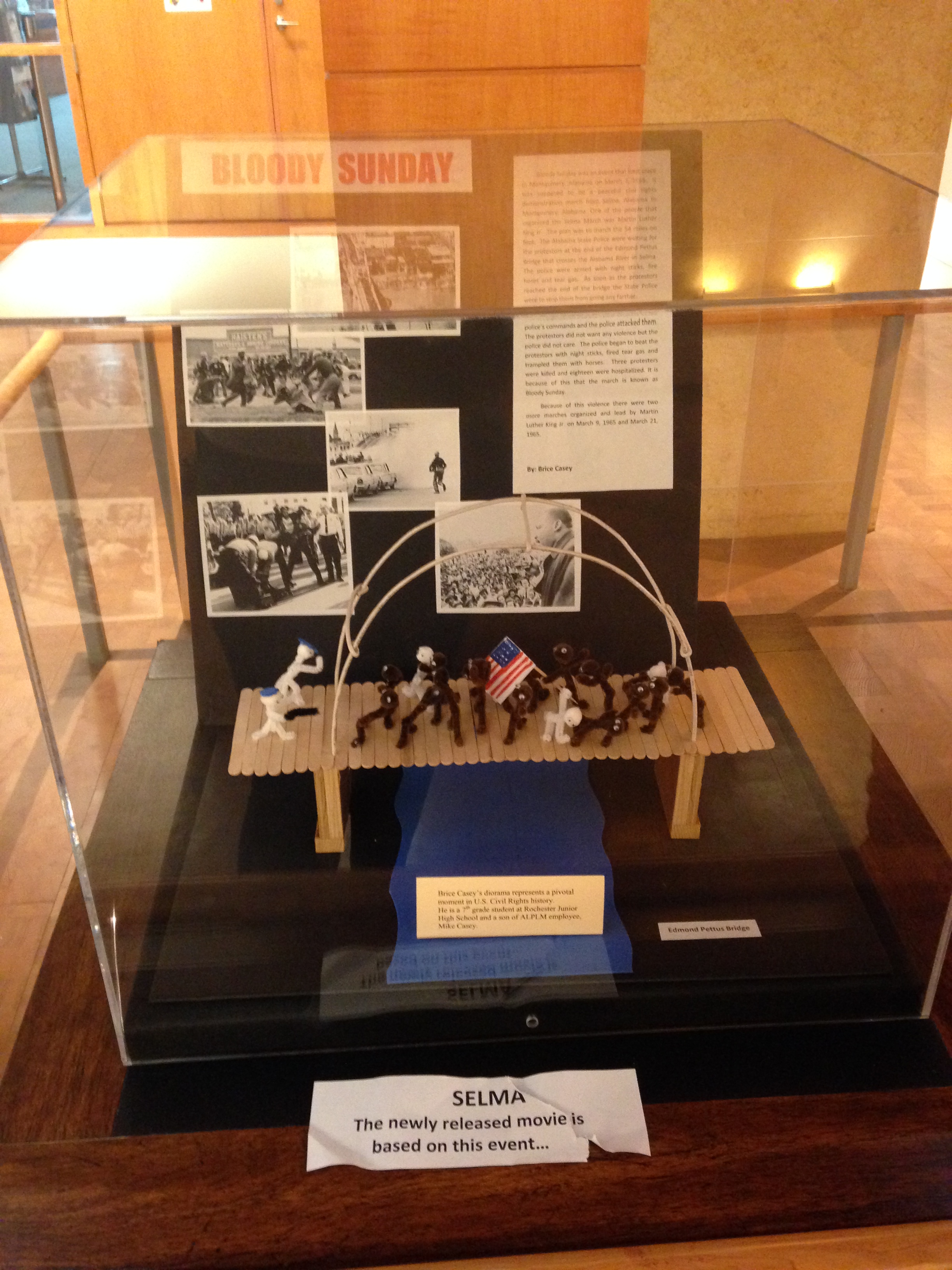

The second race-acknowledging item that I stumbled upon was in the entryway gallery of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. When I entered the building, I walked into a large, two-story space. A guard greeted me from behind a desk just to my right. Currently, both floors are being used to exhibit Civil War photographs and memorabilia. Walking around, I saw the traditional stories of Civil War veterans and the stories of their living local relatives.

Walking towards the stairs, there was a small pedestal and a case which housed a small project, titled “BLOODY SUNDAY.” A small, torn piece of paper on the front noted that “SELMA: The newly released move based on this event…” was being depicted here. This project was created by a 7th-grade student and depicted events from the Selma to Montgomery march on Edmund Pettus Bridge. The people, represented by white or brown pipecleaners, clash violently over the popsicle-stick bridge. One white pipecleaner man wrestles with a brown pipecleaner man as they both grip the tiny flag. Their googly eyes do not meet.

I commend the creator of this project and whoever decided to include it in this show. On this particular weekend, however, I struggled to make sense of the funeral re-enactment and of the city of Springfield in general. It’s not that I imagine the capitol of Illinois to be particularly progressive, but I struggle to make sense of historical events and their contemporary correspondences that do not have physical or performative markers. What is Lincoln’s legacy if it is not intertwined with the 13th Amendment? Where is that acknowledged here?

I commend the creator of this project and whoever decided to include it in this show. On this particular weekend, however, I struggled to make sense of the funeral re-enactment and of the city of Springfield in general. It’s not that I imagine the capitol of Illinois to be particularly progressive, but I struggle to make sense of historical events and their contemporary correspondences that do not have physical or performative markers. What is Lincoln’s legacy if it is not intertwined with the 13th Amendment? Where is that acknowledged here?

To examine Lincoln’s life and death without considering how it affected race is incongruous with historical reality and also just downright disappointing. With such extensive programming, exhibitions, talks, and performances, the exclusion of any kind of critical engagement with race is striking. The Springfield re-enactment not only erases the voices and experiences of non-whites, but continues the troubling trajectory that history can only be understood, and consequently re-enacted, as white.

1. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/1772000.html

2↩

2. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/02/why-do-so- few-blacks-study-the-civil-war/308831/↩

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.