Preserving Culture, or a Brief History of the Jackalope

Editor’s Note: After last week’s historic and devastating election, the jackalope may seem like a silly topic, but it is also a case study in how we mythologize and narrate a great American past that only exists as a heroic symbol. It is more important than ever to examine the myths that Americans tell ourselves about who we are, who we once were, and who we never have been.–Sara Clugage

The psyche and mythology of the American west is greatly shaped not only by its rugged landscape but by the many beasts that inhabit it. The wilderness vs. settlement distinction structures a simple understanding of American history, one particularly lacking in complex relationships between a landscape and its inhabitants. American Studies scholar Frieda Knobloch writes, “Nature makes culture possible, and a ‘culture’ looks back with a certain nostalgia to the nature that gave rise to it, at the same time that it is only through the transformation of nature that a culture understands itself as ‘advanced.’”[1] The great American West was peppered with buffalo, mountain goats, large rodents, and birds that had not been researched or discovered on the East Coast. These fantastical creatures were also part of a new hunting movement that encouraged not simply slaughtering the animal but rather carefully preserving it and bringing it back to civilization for education. While not all buffalo or mountain goats wound up in cultural institutions, many large American beasts were killed, stuffed, and displayed in museums across the United States. Large animals were often posed and displayed as if they were still alive or even placed in habitat dioramas. Institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History opened in 1874, inspiring the founding of other regional museums, such as the Milwaukee Public Museum in 1882, across the expanding country. This enthusiasm for the preserved American animal ensured a visual and material legacy of what the West once had been. The social construction of this new space was greatly shaped by its animal inhabitants, inhabitants that denoted a particular kind of Americana. As the United States expanded westward in its violent and aggressive geographic development, so did the mythology of the country.

Jackalope mount via Jackalope Junction, Wyoming

The jackalope was “discovered” by Douglas Herrick, born and raised in Douglas, Wyoming. The New York Times obituary for Herrick sets the scene: the year was 1932, and Herrick was out hunting with his brother, Ralph. He returned back with his spoils:

“We just throwed the dead jack rabbit in the shop when we come in and it slid on the floor right up against a pair of deer horns we had in there,” Ralph said. ”It looked like that rabbit had horns on it.”

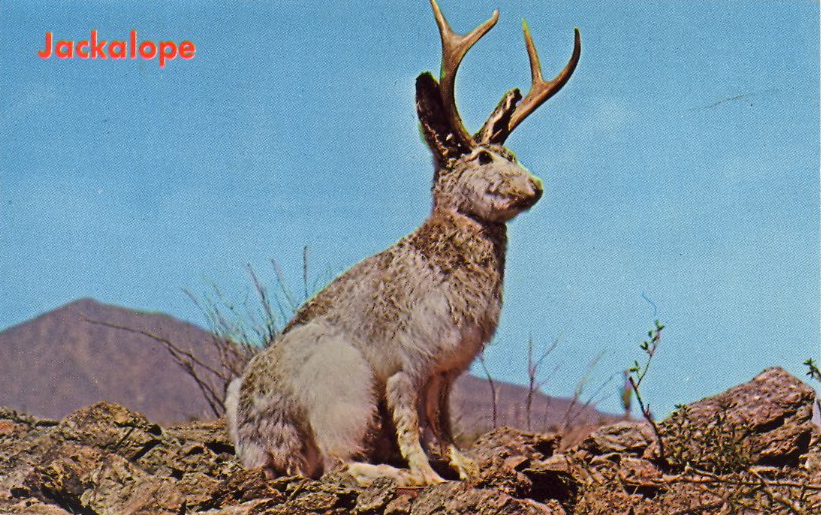

The Herrick brothers had some taxidermy experience from mail-order taxidermy catalogs. From there, the brothers set forth, outfitting deceased rabbits with horns of an also-deceased buck. A melding of the “jack” from “jack rabbit” and the horns of an antelope, the jackalope was born.

The jackalope became an overnight sensation, both as a campy myth and a highly sought-after souvenir of one’s trip west. Douglas, Wyoming became known as the “Jackalope Capital of the World,” outfitting its town square with a large sculpture and populating local gift stores with jackalope paraphernalia such as jackalope milk, postcards, and obviously, mounted jackalope heads to hang in one’s home. The town of Douglas also released a jackalope hunting license: “The Douglas Chamber of Commerce has issued thousands of jackalope hunting licenses, despite rules specifying that the hunter cannot have an IQ higher than 72 and can hunt only between midnight and 2 a.m. each June 31.” Despite the tongue-in-cheek requirements and regulations, the actual license tells a different story of the creature:

Jackalope hunting license via City of Douglas, Wyoming

Noted on the back of the license itself, the lore of the jackalope veers into a different origin story. The jackalope was not “created” but rather discovered by Roy Ball in 1829 in Wyoming Territory, more than a century before Herrick. The license also cites that there are two varieties of jackalope: a larger, more vicious sabretooth jackalope, and the smaller, less intimidating pronghorn jackalope. Only the pronghorn jackalope may be hunted with this license.

It’s no secret that the United States hit a rough patch in the early 1930s. After the crash of the stock market in 1929 which led the United States into the Great Depression, the Herrick brothers would have been experiencing a drastic shift in American culture. The struggle was real: farmers’ land dried up, cities crumbled, and families strained to get by. The jackalope allowed for folks to have a small piece of joy in the creation of this new creature and a sense of humor about its contentious origin. It was also uniquely Western and highly commodifiable: American ingenuity at its finest.

The lore of the jackalope goes further than roadside attractions, speaking to a particular kind of Western nostalgia about a time when settlers desired to create a culture that was wholly and uniquely American. If we are to consider that the Herrick brothers are the true creators of the beast in 1932, it’s worth noting that the American West had mostly been won. Wyoming Territory was officially approved for statehood in 1890. The indigenous people who called Wyoming home, like most of the remaining Native peoples of the American landscape, were quarantined into reservations peppered across the whole of the land that was theirs: the Wind River Indian Reservation was the first and only reservation in Wyoming, established in 1868. It became home to the Shoshone and Arapaho peoples.

Jackalope sculpture in Douglas, WY via Wikimedia Commons

With westward expansion, the new population of American colonizers pushed outwards towards the Pacific. Towns and cities popped up in the frontier, and technologies such as rail, automobile, and telegraph made the West accessible in ways that it never had been before. The nostalgia for a more wild West was driven by the domestication of the American West.

The great American road trip, as seen with the development of Route 66, was the heart of this nostalgic mythology. Route 66 was officially established on November 11, 1926 and was heralded as the Mother Road. Starting at Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, the road meandered westward, winding through bustling small towns toward its Los Angeles endpoint. While Route 66 wasn’t the only major road pushing westward, it certainly was the most popular. American culture became anchored by the explorations of motor tourists and the unique iconography invented to attract them.

The author at Wall Drug in 2015 (photo by the author for Dilettante Army)

Those that traveled west by a more northerly route saw frequent signs for Wall Drug, a drug store turned tourist trap turned museum turned giant gift shop. Wall Drug was established in 1931 in the town of Wall, South Dakota, just a year before the Herrick brothers made their pronghorned discovery. Wall Drug advertised for hundreds of miles, forever noting their free ice water and five-cent coffee. Every few miles, a small sign would pop out of the landscape, reminding folks that they were now just 274 miles from the infamous Wall Drug. Many of the signs and souvenirs incorporated the jackalope, and to this day, Wall Drug is one of the largest sellers of “actual” jackalopes from Douglas, WY.

It seems inevitable that the notorious jackalope would thrive in the roadside attraction, which still sees over 22,000 people per year stop by to stretch their legs en route to somewhere else. The jackalope is also a material manifestation of the pit stop, a small but enduring idea in the longer trajectory of American mythology. While the buffalo, elk, and grizzly bear all have places in the construct of American character (determination, wild individuality, and rugged exploration), the jackalope is a gentle reminder that a foundational aspect of Americana is lowbrow rural culture.

While traditional taxidermy seeks a certain seriousness, the jackalope turns away from that very legacy and legitimacy. The traditional practice of the mounted buck, arguably the most popular of all taxidermy in the 20th and 21st centuries, can be seen in many dens and living rooms across America. It is understood not only as a trophy from the hunt but as ownership of the great outdoors. Traditional taxidermy seeks to stuff and pose animals in a lifelike pose, forever gesturing their body in active poses as if they were still alive. This serious trade requires taxidermists to fully understand every muscle and movement of a particular creature. While humor and taxidermy have found places in the historical trajectory of the trade, it has never been at the forefront.

Jackalope postcard via Bad Postcards Tumblr

The jackalope inhabits a particular space within the culture of taxidermy because of its uniquely fallacious existence. While pieces of both the jack rabbit and the deer come together to create something new, the actual death of a jackalope is impossible. Historian Karen R. Jones describes the function of taxidermy in the iconongraphy of the American West:

Mounted for posterity in the sanctuary of the great indoors, the animals of the West formed a powerful necrogeography, a landscape of death that communicated a series of motifs: nature red in tooth and claw, the power of the hunter hero, the romance of imperial adventuring, and the allure of the West (both real and imagined).[2]

If the jackalope participates in this necrogeography, where is the romance of adventure in a false creature? Arguably, the jackalope lives a quantifiable existence representing a particular allure of the American West which is not only strictly imagined; it reminds us that we can all be heroes with the mere purchase of this stuffed joke. The romance of dignified taxidermy is a falsified response to the winning of the American West and the many problematic steps that the United States took to reach the Pacific.

For this reason, the jackalope operates as a co-existing entity between American history and nostalgic folklore, between inside joke and tasteless home decor. It may be a mythical creature that started as a joke between brothers and developed into an ongoing tourist souvenir, but it’s no wonder that the creature pops up in so many places. The jackalope makes sense of the production of nostalgia in American culture: it embodies the particularly American struggle of a search for a history embedded in adventure and ingenuity that does not fully exist.

[1] Frieda Knobloch. The Culture of Wilderness: Agriculture as Colonization in the American West. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. 75.

[2] Karen R Jones. Epiphany in the Wilderness: Hunting, Nature, and Performance in the Nineteenth-Century American West. U P of Colorado, 2015. 228.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.