The Christmas Bush

When I told my mom that I wanted to write something about Christmas, she solemnly said, “Christmas is about family.”

She’s right, of course, because if it weren’t for the fact that I was visiting my grandmother in Dallas, I never would have gone to the President George W. Bush Library and Museum. And I never would have seen a super-detailed recreation of the White House’s 2002 Christmas decorations, currently housed in the museum’s temporary exhibits space. And I never would have figured out what family is really all about (it’s America).

Located on the campus of Southern Methodist University—Laura Bush’s alma mater—the Bush Library building is stately, but not old-fashioned (much like America). The building’s updated Georgian architecture enables it to blend in with other campus structures while still looking presidential as hell.

As you walk into the library’s atrium, “Freedom Hall,” you’re promptly presented with an opportunity to be the true patriot you were born to be. Sign the “Freedom Registry”—using one of the two touchscreens embedded in what I can only assume is the Freedom Table—and pledge to support both the Bush Library and freedom abroad (so efficient).

From the atrium, you can enter and explore three different exhibition halls. Two of these halls house permanent displays, while the third hall is devoted to temporary exhibits (currently White House Christmas 2002).

The Bush Library, like many modern presidential libraries, is a master class in propaganda. The museum is the story that the Bushes (and their financial backers) want to tell about G.W.’s eight years in office. You’ll find that, within these walls, policy is painted in broad strokes, and the overall narrative is all sweeping ideology. From the wall text to the interactive Decision Points theater (where participants resolve Bush-era crises by listening to expert testimony and then indicating their levels of agreement by way of a slider) trigger words like “freedom,” “American lives,” and “hearts and minds” abound.

This lack of objectivity (or perhaps even a lack at an attempt at objectivity) is not unique to President Bush’s museum. As Anthony Clark explains in his article “Presidential libraries are huge failures,”

As one might expect, the history displayed in these museums is not terribly balanced; in fact, it’s often quite skewed. Instead of fairly portraying a president’s life and years in office, the newer libraries have become legacy-polishing temples that all but ignore controversy or criticism.

So, OK, the overall tone of the museum may not be unexpected. But it’s still unsettling to be smacked in the face with such a selective retelling of recent American history. As you move through the museum, you’ll find that each exhibit tells a different narrative about our 43rd president. And while none of these narratives are false, predictably, none of them are precisely true either.

In the first hall you’ll come across a display dedicated to Bush’s domestic policy. An introductory video shows George and Laura describing their youth in Midland, Texas—a place where neighbors help neighbors, Little League is a big deal, and children are safe and valued. It’s a middle-class, white, suburban childhood—summering in Kennebunkport, or Ivy League educations, are conveniently left unmentioned. George W. Bush is a man of the people.

Next you walk through a set of exhibits on Bush’s domestic endeavors; a video informs you that this is the “presidency George W. Bush wanted to have.” Here you’re surrounded by reminders of old chestnuts like No Child Left Behind, tax relief, and the Faith-Based Charities Initiative. The wall text and videos in this section emphasize Bush’s commitment to individual rights, responsibilities, and faith-based good works.

Takeaways: George Bush believes in individual rights, the duties of citizenship, freedom, and entrepreneurship. And above all else, George Bush believes in God.

The next archway off the central hall sends you straight into 9/11 America. If Bush wanted a term of carefully-executed domestic improvements, this is the presidency he got instead. This first exhibit conveys the horror and hurt that George Bush personally felt after the World Trade Center attacks. In a reflective moment on video he tells us, “I never wanted to be a war president.”

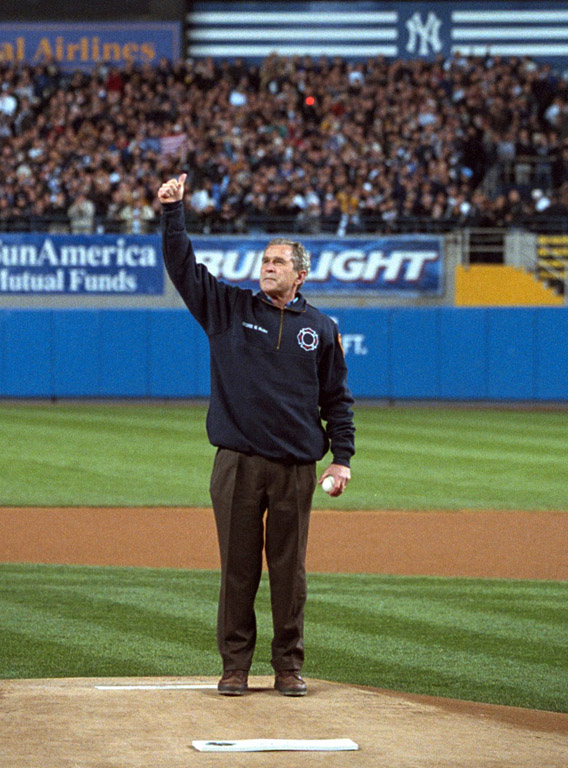

The initial rooms mirror the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York: twisted I-beams from the wreckage, TV monitors playing that morning’s coverage on a loop, pictures of shocked New Yorkers on the streets. But as you move past these bracing images, you take a strange leap forward: to a Yankees’ game.

When Bush flew to New York to meet with rescue workers and survey the damage, his main public appearance was at Yankee Stadium, where he threw out the first pitch. In the museum we hear him narrate the experience, including Derek Jeter telling him not to blow it. “They’ll boo you,” Jeter says. Bush states that he is proud that baseball was part of our nation’s healing. The episode is typical for the Bush Library—charming in an apple pie kind of way, contributing to our nation’s mythos of homespun wisdom and togetherness.

Sparse on the details, though: no particulars on the attackers; little exploration of the larger socio-political issues that motivated the 9/11 terrorists; few details regarding the implementation of the attacks on the World Trade Center. And the people who were involved in sussing out these types of details, like Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, are conspicuously absent from the whole museum. (Condoleezza Rice does make a couple of innocuous cameos. Andrew Card and Josh Bolton—two White House chiefs of staff under Bush—host the Decision Points interactive exhibit.) The Bushes would rather we forget about their administration’s more unpopular folk. Rumsfeld and Cheney probably don’t even play baseball.

Takeaways: George Bush is a leader and protector of the key tenets of American identity. You need not worry about the details of how important decisions were made—you benefit from the end result. This is not a man who debated, or changed course in light of new evidence, or in light of any evidence at all. He’s the Decider.

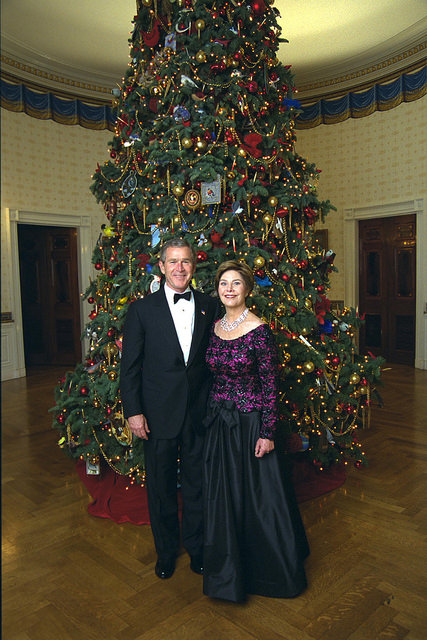

To reach the third exhibition space in the Bush Library, you take a short trip across the central atrium. Currently, this temporary exhibition room is home to a faithful recreation of the White House’s 2002 Christmas décor. We all know Christmas brings people together: this is where the two G.W.’s from the previous exhibits meet.

A trompe l’oeil recreation of the Blue Room serves as a set to hold an eight-and-a-half foot Christmas tree and all the White House decorations from 2002. The Bush Library explains that every White House Christmas has a theme; for 2002, George and Laura chose “All Creatures Great and Small.”

The tree ornaments depict birds from all fifty states, commissioned by the states’ governors from local artists. The rest of the White House was decorated with handcrafted papier-mâché models of famous presidential pets through history (note: not piñatas).

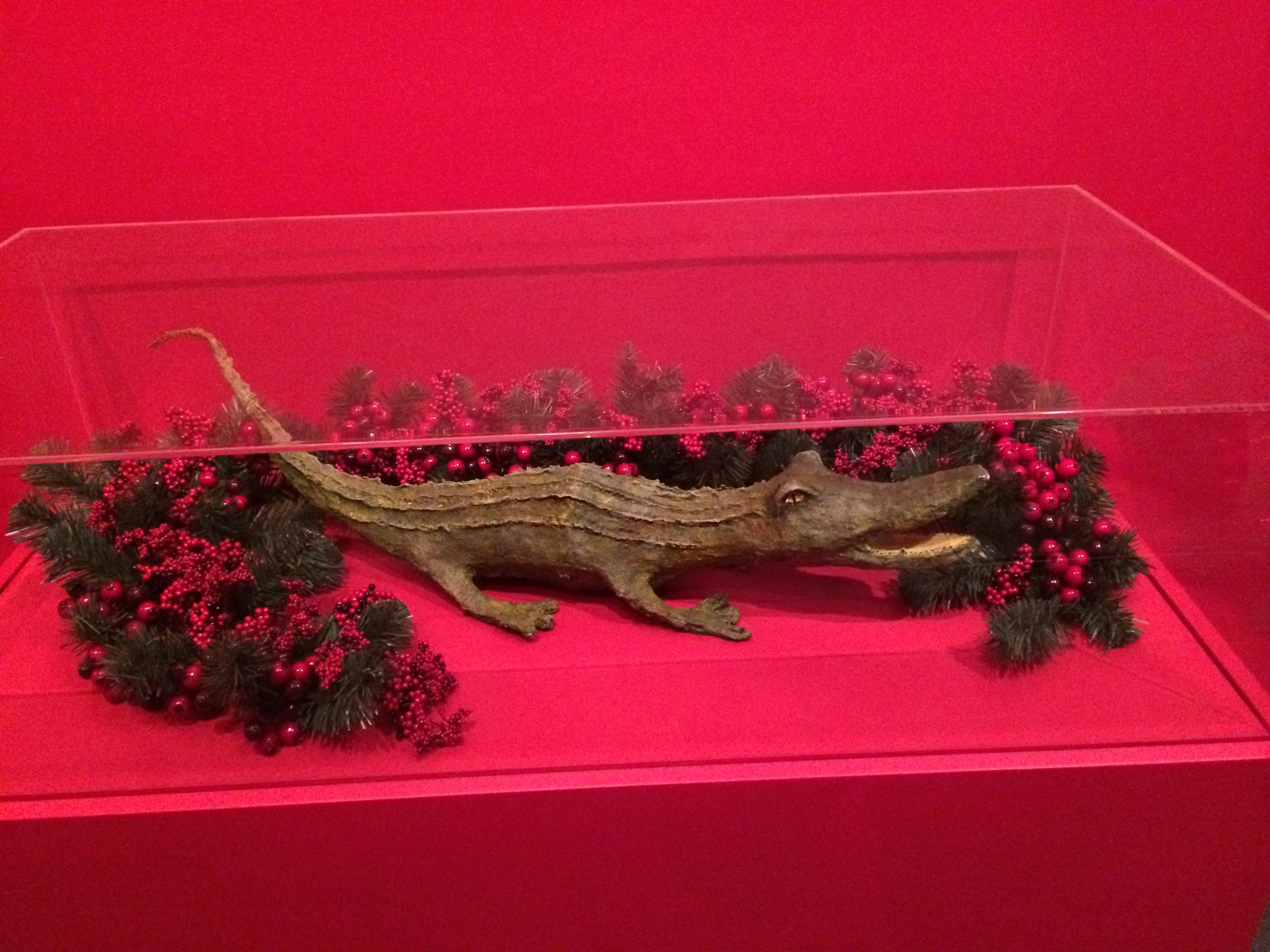

Let’s just take a beat to note that John Quincy Adams once kept an alligator in an East Wing bathtub. The model is kind of cluelessly toothy, and he’s super festive. This alligator and I understand each other.

As you first step into the third exhibition hall—and thus back in time to Christmas 2002—the transition from 9/11 to pleasant Christmas feels bizarre and jarring. A Christmas portrait shows George Bush stands with his wife in front of their Christmas tree: the very model of a normal holiday card photo (ok, for rich people). Videos projected onto the walls follow Barney, the Bushs’ dog, gamboling on a snow-covered White House lawn and trotting through the halls of the East Wing. Adams’ alligator smiles at you. This is the presidency that George Bush wanted.

But the very theme and focus of Christmas 2002 speaks to the Bushes’ attempt to reconcile the presidency they wanted with the presidency they got. In “All Creatures Great and Small,” Bush 43, who ”never wanted to be a war president,” casts himself as the genial patriarch in a national Christmas celebration.

Prior to 9/11 the White House’s Christmas themes were largely artistic, childlike, or era-specific. Three different administrations used Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker as inspiration (Kennedy, Bush 41, and Clinton). During the Reagan and Clinton administrations the annual Christmas trees were themed around old-fashioned toys, Mother Goose, Santa’s workshop, winter wonderland, a visit from Saint Nicholas, and The Twelve Days of Christmas (among others). Nixon’s Christmas themes were exclusively nature-based, focusing on flowers and foliage. And prior to the Bush 43 administration it was quite popular to decorate the White House in the style of a particular period: Early Americana, the Victorian era, and the American Colonial Period.

Christmas 2002 is part of a distinct turn—lead by George and Laura Bush—toward domestic and familial themed Christmas decorations. The first Christmas after 9/11, “Home for the Holidays,” intentionally emphasized the importance of American families, community cooperation, and togetherness. “All Creatures Great and Small” reinforces and expands upon this reassuring ideology. Laura Bush viewed the theme as a way to honor those animals that “have been such a source of comfort and entertainment to us.”

This Christmas display shows us George Bush: uncomplicated family man surrounded by cute animals. It paints him as a caretaker and a paternal figure. And, importantly, because the display includes previous presidential pets, it positions President Bush within a history of father-figure presidents. Laura Bush, in a 2002 interview, even cited a “presidential tradition of having animals around” as inspiration for the 2002 Christmas display.

The motivating drive behind “All Creatures Great and Small” is to unify and consolidate and American identity. All 50 states are represented with bird-themed Christmas ornaments. Presidential families throughout history are made relatable by way of their furry friends (or alligators). And George Bush is cast as the latest in a long line of homespun political heroes. Through “All Creatures Great and Small” the Bushes enjoy a moment of controlling the narrative within the context of presidency that had been far from their ideal. For the Bushes, when the going gets tough, it’s time to comfort yourself with the predictable and ubiquitous structure of the American nuclear family.

The temporary display space has been home to other exhibits, of course. If you visited the museum in May 2014 you would have seen a collection of President Bush’s paintings of world leaders (as usual, Putin looks pissy). In the summer and fall of this year the museum hosted a retrospective of American fashion designer Oscar de la Renta.

But the 2002 Christmas display is unique in that it provides a sense of how the Bushes attempted to shape their public narrative while in the White House, while you’re in a carefully constructed shrine to them. It’s a Very Meta Christmas.

*Want to watch puppets have a super lot of fun at the George W. Bush Library and Museum? Of course you do.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.