The Trump Who Cried Witch: Unruly Language and the American Witch Hunt

The “witch hunt” has been re-imagined and re-introduced in this cultural moment because an unfortunate tweet posted by our 45th president: “This is the single greatest witch hunt of a politician in American history!” Social media has introduced the American public to a technology landscape where politicians are able to directly interact in the public sphere, so Salem’s congressman, Seth Moulton, responded a few hours later: “As the Representative of Salem, MA, I can confirm that this is false.” The tongue-in-cheek response by Moulton shows his concern over Trump’s casual assumption of victimhood.

A distaste for one’s own political treatment falls outside of the historical legacy of the witch hunt. A witch hunt, or public investigation and persecution of the suspected wrongdoer, has many long-lasting implications for society: damaged personal reputations, legislative shifts, and effects on the treatment and understanding of the accused or their affiliated groups. Trump’s eager ownership of martyrdom status, however, suggests that he is interested in how he himself is affected rather than how the masses that elected him could be affected. The possibility that Trump is being targeted as one, lone person seems unlikely when we consider any large scale social injustice such as the Salem Witch Trials, the most influential witch hunt in American history. While late night hosts and academics have been quick to respond to Trump’s witch hunt claims, the cultural implication of his supposed innocence taints a heavy history that only recently has been grappled with.

Usage of “witch hunt” in modern times highlights a particular type of wrongdoer, one often targeted for participating in a belief system, practice, or group that lies outside of acceptable expectations in some form. To drop “witch hunt” into a conversation or use it as a retort against an allegation stirs up the anxiety of being targeted unjustly; it is a grandiose term that will haunt the accused even if they are proven innocent. “Witch hunt” is often peppered into political scandal: McCarthy’s red scare of the 1950s, the Whitewater scandal of the Clinton estate in the 1990s, and even the Lewinsky scandal of Bill Clinton.[1]

A more recent political witch hunt was conducted not of Trump, but by him. Notably, the bizarre “birther” accusations regarding the speculation that President Barack Obama was born in Africa came from Trump himself. Trump demanded that Obama release his birth certificate to prove that he was legally eligible to become president. Despite the release of the birth certificate in 2008, Trump continued to prod and accuse Obama of producing or destroying official records that would note where he was born, only giving up the issue in the fall of 2016.[2] Can the invoker of a witch hunt also be the target of one? The question itself serves as a reminder that the one who cries wolf (or witch in this case), may not be so easily trusted when being called out for his own wolfness (or witchness, as it were). Trump showed little regard for the use of rhetoric or its larger effects in this odd equation, reminding us that language plays a large role in how we identify and speculate on the definition and legacy of a witch hunt.

The Salem Witch Trials are a well-known episode woven into the tale of American history. Consequently, the demonization and destruction of women in Puritan culture has had a lasting impact on the ways in which women can and ought to be part of the American social imagination. Of the 19 people that were tried, found guilty, and executed, 14 were women. Many of them were described as irritable or outspoken, and many of them neglected the social norms and expectations of the era.

Language was a great indicator of status and class in Salem, and the words of women were policed. The accusations against the supposed witches of Salem are described in great detail and often highlight how language was used not only to define how spoken language ought to be used, but how stepping outside of those rules meant grave danger for some women. In her essay “Female Speech and Other Demons,” scholar Jane Kamensky analyzes the way that 17th century Puritan theologian William Perkins described women’s unruly speech.

He listed seven ways that witches might arouse suspicion, and five of these centered on the spoken word: a “common report” or “notorious defamation” of being a witch; the testimony of a fellow witch; the “mischief” that followed either from the witch’s curses on her “quarreling or threatening”; an finally, the quality of her speech upon examination.[3]

The women of Salem had little agency to speak out against their own accusations. There was almost no way to claim one’s own innocence while at trial, especially since such vague terms of “quality of speech” might be raised as damning evidence, ending in a guilty verdict, punishable by death.

The persecution of accused witches, then and now, has real consequences in many ways. There’s the large-scale social aftermath as we try to understand what happens when we demonize particular members of a community and send them to their death. There are also the smaller ways that live on in smaller narratives: how we interact on a personal level, who tells what stories, and who continues to be tied to this violent past. These effects are not unique to witch hunts or their trials but rather are attached to all kinds of violence continually perpetrated against individuals, communities, and governments.

When we consider the smaller details of how a witch hunt affects the individual family structure, we can start with one person, one to whom I happened to be related. Rebecca Towne Nurse was convicted of witchcraft and then executed by hanging on July 19, 1692. Her name and story were made famous in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, a play that has been produced again and again, including a popular television movie and a successful Broadway production. It has also been produced by many, many high school dramatists since its publication in 1953.

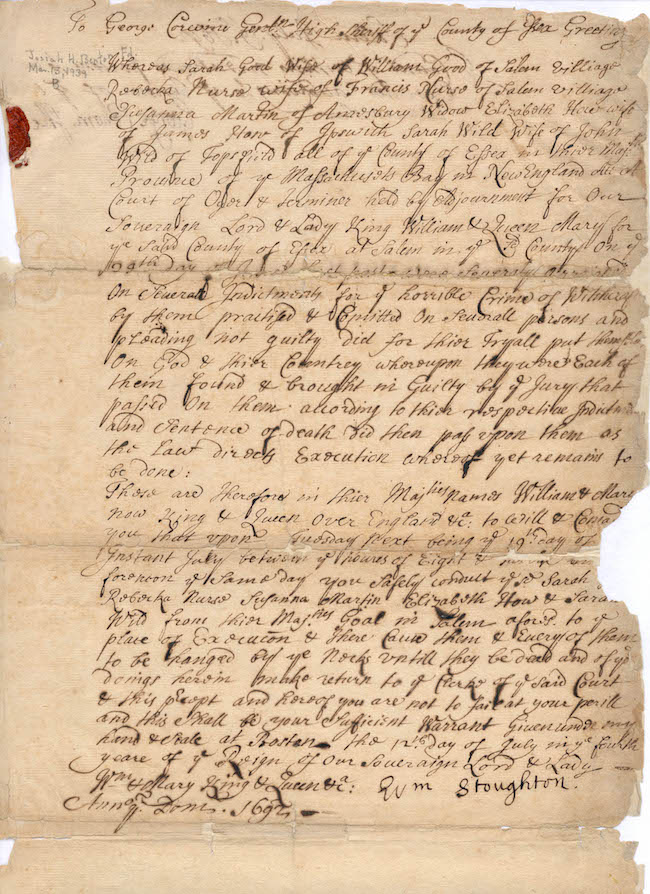

Warrant for the Execution of Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin , Elizabeth How, and Sarah Wilds. Image via The Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project

Rebecca Towne Nurse was one of the oldest women to be tried for witchcraft during the infamous trials that took place in New England during the late 1600s. She was the eldest child of William Towne and Joanna Blessing, who came to Massachusetts from Yarmouth, England. Nurse was born in England in 1620 or 1621, and she traveled from England by boat with her family and younger siblings in 1635. In her early twenties, Rebecca married Francis Nurse, who produced basic household crafts and provided his growing family with a comfortable life. Rebecca and Francis had 8 children—four daughters and four sons—and they needed a sizable home to raise them in. Their homestead, located in current day Danvers, Massachusetts, was formerly a part of Salem Village and was acquired by lease for the family in 1678. The family ran it as a successful farm and improved the structures on the property, which included the large home where the family lived as well as a few small barns for storage.

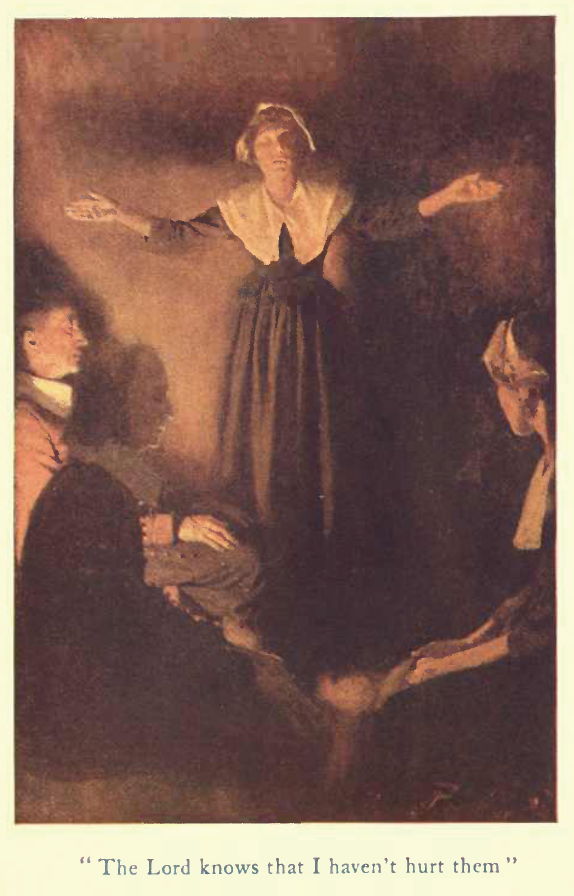

It’s thought that the general success of the Nurse family brought their undoing; while many women accused of witchcraft were poor and young, Rebecca was 71 when her trial began on March 23, 1692. She adamantly denied any relationship with the devil or the witchcraft associated with him: “I can say before my Eternal Father I am innocent and God will clear my innocence….The Lord knows I have not hurt them. I am an innocent person.”[4] Rebecca Towne Nurse was accused by Ann Putnam Jr., Ann Putnam Sr., and Abigail Williams. The Putnams were neighbors of the Nurse family and may have targeted Rebecca because of a land dispute, or perhaps it was because Ann Putnam Jr. and Abigail Williams were bothered by Rebecca’s accusation that the girls were practicing their own work of the devil when they were caught being mischievous.

The details of this trial are known because it produced one of the first thorough documentations of legal proceedings in North America. The papers trace the trial’s every testimony and accusation. These transcripts were, however, still dictated by those in power, who were not necessarily unbiased in their descriptions. The Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project describes some of these conflicts of interest:

The examination of Rebecca Nurse was recorded by the Reverend Samuel Parris, whose own young daughter Betty was one of the accusers together [with] Betty’s cousin, twelve-year old Abigail Williams. He writes that the examination opened with (Judge John) Hathorne turning his attention not to Nurse, but rather to Abigail Williams. Williams reported to the magistrates that the apparition of Nurse had just that morning, as well as on previous occasions, afflicted her. Shortly after this statement, Ann Putnam, Jr. launched into a “grievous fit” and before Rebecca Nurse even began to testify, the tone of the examination had been set.[5]

Rebecca was originally found not guilty at trial, but her accusers rose to fight the verdict, telling the jury about an incriminating statement Rebecca had made during the trial. When asked again about this statement, the partially deaf defendant did not respond to the question. Citing this as evidence against her, the judge asked the jury to deliberate once again, who came back later with the verdict of guilty. It is here that the power of language, even its absence, is bent and altered to get the verdict desired.

Howard Pyle, “The Lord knows that I haven’t hurt them” (illustration of Rebeca Nurse). 1907. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Rebecca Towne Nurse was executed by hanging on July 19, 1692. According to local lore, Rebecca’s body, unfit for a proper burial, was placed in a shallow grave near the gallows where she was hung. In the safety of night, her family returned to gather her remains and give her a proper burial at the back of the property of the homestead. The impressive monument that stands tall in the small cemetery was later erected in 1885 by her descendants, many of who make up the Towne Family Association (TFA), which is dedicated to keeping her memory and story alive. The 325th anniversary of her death is this year, and a ceremonial wreath will be displayed after a public ceremony on this July 19th, 2017.

It only took ten years for the Salem witch trials to be declared illegal. Only one out of six accusers apologized: Ann Putnam Jr. released a formal statement regarding her role in the accusations in 1706. It was not until 1957 that the state of Massachusetts formally apologized for the murderous witch trials. In 1991, the town of Salem erected a monument for those that died. The hundreds of years that passed before the witch trials were appropriately acknowledged speaks to the anxiety that holds on through time: perhaps there was some ounce of truth to the witch trials, or perhaps the shame that came with this history was too much to bear and Massachusetts hoped to sweep it under the rug.

I am a direct descendant of Edmund Towne, Rebecca’s brother, making her my distant aunt. I am the last Towne child in my bloodline. My mother is an only child and took my father’s name after marriage, closing out this Towne chapter. I first visited Salem when I was in middle school, and I remember my mom pointing out every sign with her name on it, reminding me that she was one of our own. In the summer of 2016, I drove through Salem and stopped by the Rebecca Nurse Homestead in Danvers, Massachusetts. Despite the humidity and heat of the August day, my partner and I trekked back beyond the home itself, closed for the day, and headed back to the cemetery on the property. Her monument stood tall, reminding the living that, “The world redeemed/ from Superstition’s sway/ Is breathing freer/ for thy sake to-day.[6]”

Rebecca Towne Nurse was tried, found not guilty but then guilty, and died at the age of 71, the same age as Donald Trump at the time of this publication. While both individuals have a contentious relationship with persecution, the modern day legal system does not acknowledge any wrongdoings when it comes to the occult or paranormal. Any prosecution of a powerful, old, white guy, at the height of Western power and privilege, would be based in earthly wrongdoings, whether it be for Trump’s possible collusion with Russia or another possible scandal. Rebecca Towne Nurse was failed by a legal system caught up in accusations and celestial hauntings, her age and sex were used against her in a way that Trumps identity will never work against him. If we are to “breathe freer today,” we ought to be reminded of our troublesome past, plagued by injustices of power that are still present with us today. Language is a key component to the way that the legal system operates in the United States and is directly impacted by those in power, even when those at the top cry “witch,” or “wolf,” on Twitter, freely, in the middle of the night.

[1] Pearce, Matt. “What’s the ‘greatest witch hunt of a politician in American history’? We asked the experts.” Los Angeles Times. June 17, 2017. Accessed June 18, 2017. http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-pol-witch-hunts-20170519-story.html.

[2] Barbaro, Michael. “Donald Trump Clung to ‘Birther’ Lie for Years, and Still Isn’t Apologetic.” The New York Times. September 16, 2016. Accessed June 23, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/17/us/politics/donald-trump-obama-birther.html?mcubz=2&_r=0.

[3] Kamensky, Jane. “Female Speech and Other Demons: Witchcraft and Wordcraft in Early New England.” In Spellbound: Women and Witchcraft in America, 25-52. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1998. 29.

[4] “The Salem witchcraft papers, Volume 1: verbatim transcipts of the legal documents of the Salem witchcraft outbreak of 1692 / edited and with an introduction and index by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum / revised, corrected, and augmented by Benjamin C. Ray and Tara S. Wood.” Accessed June 8, 2017. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/texts/tei/swp?div_id=n94.2&print=yes.

[5] Madden, Matt. “Examination of Rebecca Nurse of Salem Village.” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. Accessed June 12, 2017. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/people/nursecourt.html.

[6] Rebecca Nurse Homestead Cemetery (Danvers, Essex County, Massachusetts), Rebecca Towne Nurse headstone, personally photographed, 15 August 2016.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.