Wedding Cake Toppers: Miniatures, Excess, and Fantasy

Figure 1. Whitcomb, Jon. Periodical Illustration. n.d. 4 color print. Graphic Design and Illustration. https://jstor.org/stable/community.19325733.

Cakes are like clowns. Both are so deeply imbedded in our culture that their strangeness is ignored.

—Barbara Zucker, “Stella Chasteen,” Heresies vol. 1, issue 4 (Winter 1977-78)

As someone who delights in studying overlooked objects in visual culture, I admit that the wedding cake topper, for all its ubiquity, is particularly niche. If cakes are like clowns, then wedding cake toppers are like clowns’ shoes; they’re even further removed from whatever constitutes the American visual-cultural “center” than the already-fringe entities they adorn.

Decorative, diminutive, frilly, and frosted, wedding cake toppers are so far off the radar of mainstream scholarship that to say they have a reputation for being frivolous would be disingenuous—they scarcely have a reputation at all. The reason for the dearth of analyses on wedding cake toppers is anyone’s guess. I would venture that their frequent incorporation of unstable materials (gum paste, wax, marzipan, celluloid, chalkware) combined with their gendered associations (both in iconographic content and in their sentimentalized afterlives) and status as mass-produced commodities (not high art, and likely lower than low art) are enough to deter Serious Scholars of Fine Art.

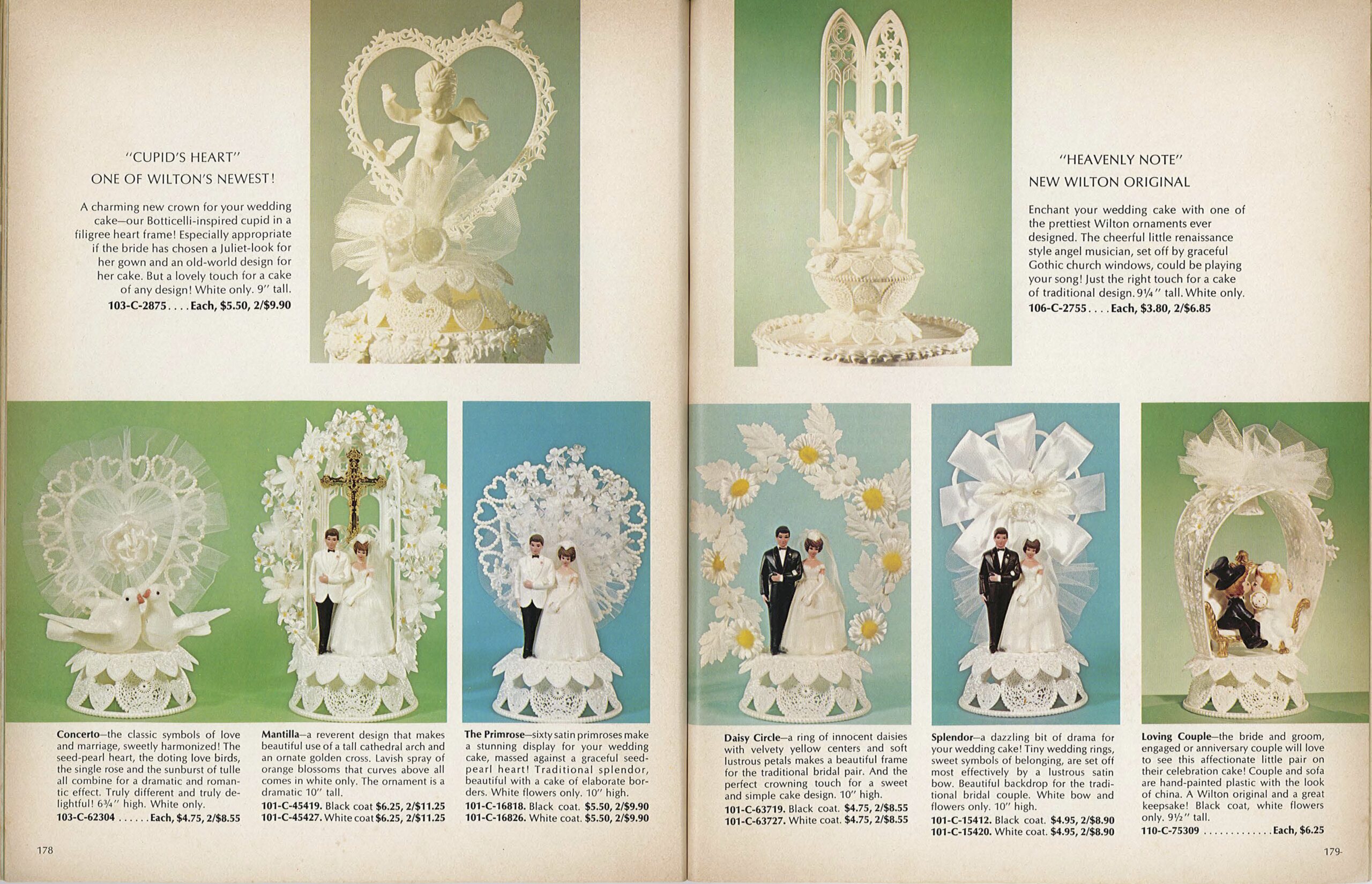

Figure 2. Two page spread scan from Cake & Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton: a month-by-month calendar of cake and party ideas (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises Inc., 1973) 178-179.

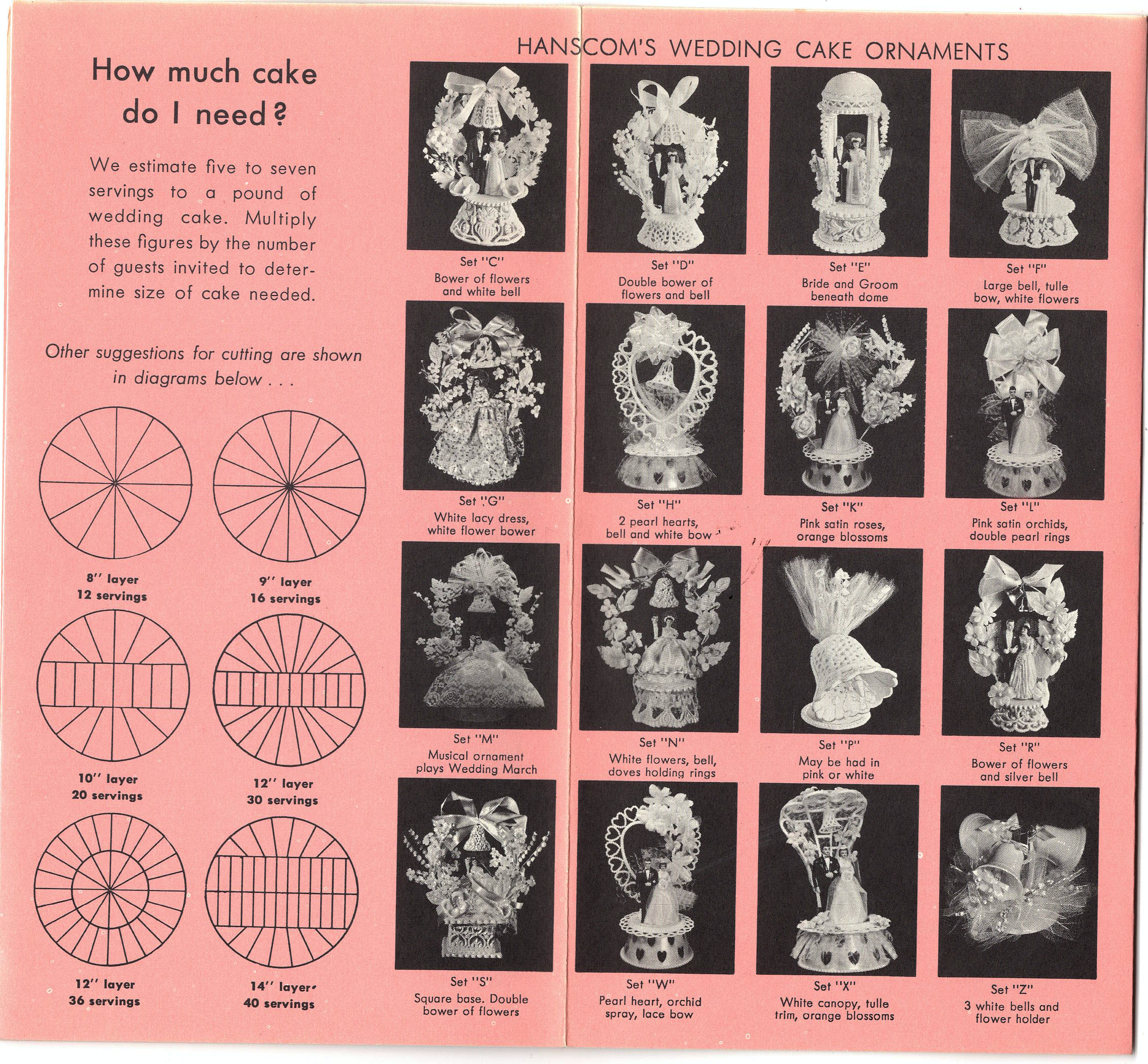

Figure 3. Hanscom’s Wedding Cake Ornaments. Scan from Wedding Cakes (Philadelphia: Hanscom of Philadelphia, ca. 1950).

Like most seemingly innocuous objects, wedding cake toppers have much to reveal about the social values and temporal contexts of those who manufacture, purchase, and use them. Because they are additive, cake toppers appear to be purely “extra”: an aesthetic excess; an extravagant ornament; an inessential and nonfunctional object without use value. But decoration provides its own function, and cake toppers reflect historic, present, and even fabulatory future structures of social, economic, and aesthetic meaning. Though these ornaments can reify the patriarchal, institutional norms of marriage, they are supplementary, showy, and slippery. Bundled accumulations of imaginative visions, they speak to modes of community and subject that can exceed these narrow bounds.

Wedding cakes are so packed with symbolism it is hard to know where to begin.

—Michael Krondl, Sweet Invention: a history of dessert (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011), 321.

A Genealogy of Wedding Cake Toppers

The category of wedding cake topper is a broad and abundant one, with many variations. Though my exploration of wedding cake toppers in this article has finite bounds (as I primarily consider these objects post-1890 in the United States), the ornaments within its scope are still too numerous to allow an exhaustive analysis of every example. My goal is not to supply an encyclopedic treatment of these materials, but to provide a scholarly framework for engaging an untapped repository of American visual and material culture. To accomplish this aim, I will present a brief history of the rise of the wedding cake topper, propose loose categorical distinctions for types of cake toppers, and consider how these ornaments operate.

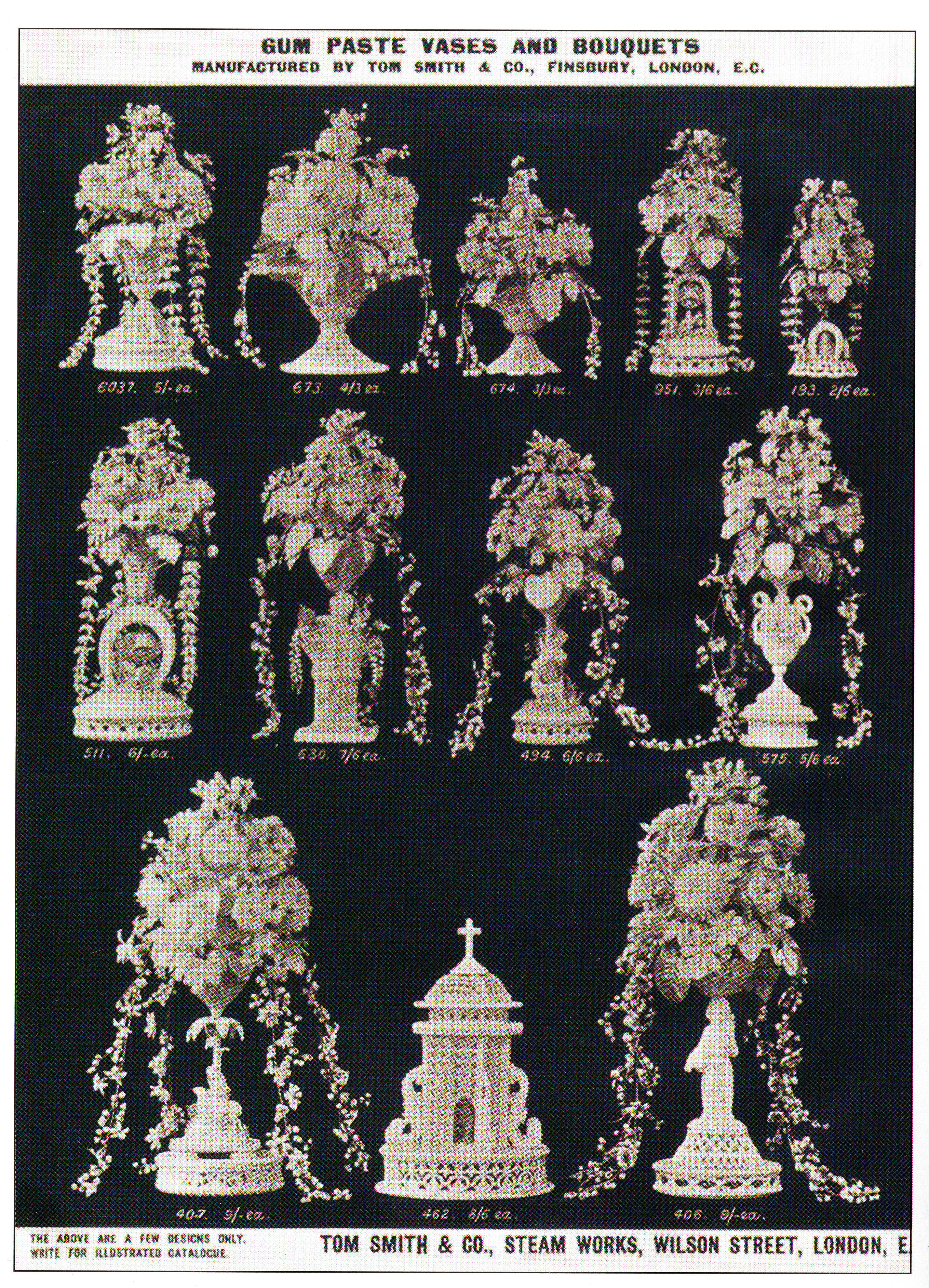

American wedding cake toppers—as we understand them today—date back to nineteenth-century marriage rituals.[1] Royal, aristocratic, and wealthy Europeans set the trend of “high rise” cakes “decorated with mounds of sugar sculptures” as early as 1840.[2] Cakes with columns, crowns, cupids, portrait medallions, ornamental statues, blossoms, and pearls made from confectioners’ sugar paste “would have been available only to the wealthiest,” due to the “sugar work, which was cost prohibitive to the masses.”[3] These styles led to popularized iterations by the 1890s: “The cakes were not as grand as the royal cakes, of course, but were nevertheless elaborately adorned with flowers, symbols of love, plus the soon-to-become-popular bride and groom cake toppers that could be removed from the wedding cake and kept as a keepsake for the ages.”[4]

Figure 4. “ Advertisement for Tom Smith wedding cake toppers made from gum paste. c. 1900.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 12.

Figure 5. Luks, George, 1866-1933. Wedding Cake. 1910-1915. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 63.5 cm. Chrysler Museum. https://jstor.org/stable/community.13934913.

Attachable wedding cake toppers of artificial flowers “became the first arrangements that could be removed by the newlyweds and placed under a dome as a keepsake of their wedding” in the 1880s, leading to other new removable toppers like cupids, joined hands, bridal slippers, doves, rings, and horseshoes. In 1892, a Scottish firm advertised in the British Baker their patented icing powder creation: a bride and groom cake topper, “a harbinger of an idea which was to run around the world in the mid-twentieth century.”[5]

With growing techniques for mass production, decorative and opulent tchotchkes of the wealthy became increasingly abundant and affordable to an emergent middle-class consumer. By the late 1890s, the United States would become “the forerunner in the production of mass-produced bride and groom cake toppers,” likely “made in molds,” leading to a meteoric rise in their presence by the turn of the twentieth century.[6] These American ornaments were “of a much more representational and symbolic kind” than European counterparts.[7] Bride and groom ornaments became standard fare by the 1920s, as well as infantile Kewpie couples.

Figure 6. “c. 1925/1940, Probably made before WWII.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 140.

These early instances of wedding cake toppers prefigure the tropes and motifs that continue throughout the twentieth century and remain popular today. In general, ornaments fall under two broad visual categories: (1) symbols and (2) icons. I invoke these terms in their semiotic sense.[8] Symbolic wedding cake toppers employ associative imagery reliant on societal conventions of love, prosperity, and good fortune; iconic ornaments are those that intend to resemble or bear likeness to the married couple, thereby both standing for and representing their union. Symbol and icon are not mutually exclusive classifications. Elaborate wedding cake toppers frequently synthesize several elements from both typologies.

Figure 7. “c.1930/1950. This particular style and composition was popular into the 1950s. … American made. The dove and base are made of food product.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 156.

Figure 8. “Concerto—the classic symbols of love and marriage, sweetly harmonized!” Scan from Cake & Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton: a month-by-month calendar of cake and party ideas (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises Inc., 1973) 178.

Many wedding cake toppers signal connections to tradition and the past. Symbolic toppers—cherubs, flowers, clasped hands, horseshoes, slippers, shoes, cupids, bells, doves, and wedding bands—do not depict the wedded couple directly, but allude to culturally constructed, internalized, and reproduced notions of the ideal and virtuous married couple.[9] For example, the popularity of the dove, “the bird of love,” instantiates the importance of fidelity and purity: “their gentle cooing and apparent faithfulness to their mates made doves…inevitable symbols not only of love but of the kindred virtues of gentleness, innocence, timidity, and peace,” and because “Aristotle wrote that doves are monogamous…faithfulness to one mate became part of the lore of doves.”[10] Although the doves that grace wedding cake today might not instantly call to mind Aristotelian faithfulness to their audiences, they remain vestiges of this ancient ideology and carry that significance with them.[11]

The conservative appeal of traditional iconic bride-and-groom toppers is self-evident. These objects are often heavily invested in pictorializing Eurocentric, heteronormative ideals of marriage life. The figures stand with a stiff, straight, vertical posture and the rigid frontality of Byzantine emperors or ancient Egyptian monarchs.[12] Some also bear a likeness in scale and material to cheap, mass-produced saints and divine beings. Early examples that continue throughout the 20th-century depict able-bodied, slender, gendered couples, with men standing taller than their wives. These duos are essential the “Platonic ideal” of American man-and-wife passed off as universal, as these stock figures were intended to appeal to any and all potential consumers. Each subsequent variation of the iconic, representative wedding cake topper points back to this traditional origin.

Figure 9. “1940/1950. Not Marked. Hand painted details.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 102.

Figure 10. Photograph I took on my iPhone in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Artwork depicted is Menkaura (Mycertinus) and queen, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4, reign of Menkaura 2490–2472 B.C.

But symbolic and iconic wedding cake toppers alike do more than gesture to their historic associations, they also form a visual language that defines what marriage is and what a couple should be. Symbolic iterations define marriage in the abstract, while iconic versions convey what kinds of people occupy a place in the structure of marriage. The cake toppers may relate to an ongoing web of nostalgic and sentimental dreams of “the good old days,” but they additionally signal the specific marriage and partnership of the individual couple in the moment of their marriage. In this sense, each cake topper, when activated—when chosen for use and then enfolded into a ceremony—performs as a marker of the couple in real time. For all the baggage each cake topper carries, they must also be more than these historic links in the current time of their use, as each ceremonial, celebratory context offers occasion for new associative readings to join and coalesce with their predecessors.

Wedding cake toppers also present dreams that couples and their communities may share when envisioning their futures. They can provide the material basis upon which individuals and groups imagine possibilities. Even with symbolic and iconographic visualities that suture them to the past, and their ritualistic usage which anchors them to the present, wedding cake toppers are always absorbing and refracting hopes and wishes for an interminable tomorrow. The horseshoe, to take one example, simultaneously reaches towards historic customary tokens of good luck, asserts the present-day ceremony of its specific celebratory couple, and casts anticipatory faith in fortunes to come.

But future forecasting aside, the symbolic and iconographic wedding cake toppers are already fantasies, even in their past- and present-tense senses. “The model is…an abstraction or image and not a presentation of any lived possibility.”[13] Whether a symbol invoking eternal constancy, a more “naturalistic” depiction of a bride and groom, or a more wacky and weird set of infantile dolls, all wedding cake toppers are imaginative ideations that speak to hopes, aspirations, and desire.

On Affirmation—

Additive, subjective, romantic, imaginative, personal, autobiographical, whimsical, narrative, decorative, lyrical, architectural, sculptural, primitive, eccentric, local, specific, spontaneous, irrational, private, impulsive, gestural, handwritten, handmade, colorful, joyful, obsessive, fussy, funny, funky, vulgar, perverse, mannerist, tribal, rococo, tactile, self-referring, sumptuous, sensuous, salacious, eclectic, exotic, messy, monstrous, complex, ornamented, embroidered, articulated, spatial, light-filled, delicate, warm, open, questioning, sharing……

—Joyce Kozloff, “An Answer to Ad Reinhardt’s ‘On Negation,’” 10 Approaches to the Decorative, 1976

Decorative Excess

A wedding cake topper can be symbolic and/or iconic, abstract and/or representational, past- and/or future-looking, but all iterations function as materialized fantasies. While symbolic cake toppers gesture towards intangible and transcendent concepts of fidelity, chastity, and love itself, their iconic counterparts ground those abstractions into vehicles of the idealized, normative body. But what is it about these materializations—the symbolic and iconic forms of the wedding cake topper—that makes them so conducive to mediating fantasy, abstract and embodied? And what kinds of possibilities might reside in these fantasies?

Wedding cake toppers, being extraneous and additive, seem to have no pragmatic value. Decoration has its own use, and surely if there is a function that wedding cake toppers accomplish in addition to mediating fantasy, it is decorating. Wedding cake toppers inspire imagination, and thinking through the specific decorative context of the cake ornament can illustrate the potential of those fantasies.

Feminist art historians and artists have already demonstrated the radical and subversive potential of decoration and excess, especially insofar as its relevance to people who have been construed as excessive, or marginal, or outside the scope of normative, canonical, patriarchal, Eurocentric art history. In the 1970s, early pioneers of the Pattern and Decoration movement in the United States decoded the not-so-subtle premises underlying modernism’s distaste for ornament. As Valerie Jaudon and Joyce Kozloff assess: “the prejudice against the decorative has a long history and is based on hierarchies: fine art above decorative art, Western art above non-Western art, men’s art above women’s art.”[14] In the same issue of Heresies, Melissa Meyer and Miriam Schapiro coin the term femmage for assemblages of materials collected, saved, and recycled by women, writing “the decorative functional objects women made often spoke in a secret language, bore a covert imagery,” and asserting that gendered works without status in mainstream art deserve their own tending.[15] These articles join others throughout the magazine in highlighting decoration as a noteworthy topic of exploration, specifically in formulating a feminist approach to visual culture.

Similarly, feminist artist Pat Lasch, an early member of the pioneering A.I.R. Gallery, transforms acrylic paint and wood into elaborate, lush, ruffled cake sculptures in the spirit of her pastry-chef father. His adage—“If you made a mistake, put a rose on it”—not only applies to Lasch’s cakemaking and artmaking, but attests to the additive nature of cake adornment.[16] In 1979, the Museum of Modern Art commissioned a 5-feet-2-inch-tall cake sculpture by Lasch for its fiftieth anniversary, but when Lasch reached out to MoMA in order to include that sculpture in a 2017 retrospective, she learned the sculpture had never been accessioned into the museum’s permanent collection and seems to have been discarded.[17] The museum released the following public statement:

The Museum of Modern Art commissioned this object as a decorative element for its 50th-anniversary celebration. While it was not intended for the collection or future display at the Museum, it was kept in our storage facilities for many years. Our recent research indicates that by the late 1990s it had deteriorated beyond repair, and was subsequently discarded.

Lasch remarked: “How can you lose something that’s 5- feet-2-inches tall? It’s like losing my mother!”[18] The MoMA’s institutional neglect of the commissioned sculpture, as well as its explanation that the object was “a decorative element,” convey the ways in which decoration becomes excess deemed unnecessary and discardable. Meanwhile, Lasch’s comparison of the sculpture to her mother is humorous, but also suggestive of an animate presence.

Lasch continues to make cake sculptures complete with ornamental blossoms and gilded trim, implying her personal and political stakes in the cake-as-decorative remain as potent as ever. Her work itself provides a temporal bridge between earlier ideologies and more recent treatises, like Julia Skelly’s Radical Decadence: Excess in Contemporary Feminist Textiles and Craft, in which she proposes “the ostensible ‘excessiveness’ of craft materials—positioned as superfluous, decorative, and unnecessary in traditional and modernist art histories—make them the perfect materials for the representation of ostensible excesses in the lived experiences of women,” and that “radical decadence is a deliberate form of excess, or of exceeding ideological (as well as spatial) boundaries.”[19] Judith Schaechter, an artist who works in stained glass, employs a “militant ornamentalism” in which the decorative and the subversive are intertwined. As she declares, “I defy anyone to prove to me that decorativeness and ornamentation is anything less than the holiest of holy pursuits. To ornament something is to make it extra special.”[20] Or, as the homepage of interdisciplinary journal Decorating Dissidence declares: “The decorative is political.”[21]

These reclamations of the decorative hinge upon art objects and materials with craft associations., and stake their political resonances upon the process of making. Though some bespoke cake ornaments are handmade from confectionery elements (sugar, gum paste) and are therefore the result of handicraft, most cake toppers are mass produced. As commodities, cake toppers mask and hide their origins and places of manufacture; the hands of their makers are occluded to appeal to consumers.

The cake topper, in the context of the cases in this article, is more of a ready-made rather than something created from scratch. Thinking of Meyer and Schapiro’s femmage as an accumulative remixing of found objects and materials, I believe we still might be able to locate the certain fantastic richness of the cake topper in a different sort of creative act.

Thus the minuscule, a narrow gate, opens up an entire world. The details of a thing can be the sign of a new world which, like all worlds, contains the attributes of greatness.

—Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space: The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Places (1958; repr., Boston: Beacon Press, 1994)

Self-fashioning and world-making

I propose that one might consider the act of decorating with the wedding cake topper its own creative act, or provide the circumstances to inspire creative ideations. Historically, or at least implied and suggested in the many reference materials I used for writing this article, it seems that the bride chooses the wedding cake topper, although any spouse can make this decision. Though dependent on circumstances like economic access and degree of bridal agency within the specific marriage context, there are degrees of agency and subjectivity in brides choosing—and often altering—their cake toppers. Decorating, arranging, and participating in the tableaux, performances, and ceremonies around the cake topper are elements that enable moments for supplementary narrative and fantasy, which then occasion modes of self-fashioning and world-making.

Early twentieth-century examples of wedding cake toppers demonstrate efforts to personalize the mass-produced paradigms. In her wide-ranging catalog of collectible wedding cake toppers, Penny Henderson notes:

Many cake toppers were personalized; that is, made to resemble the wedding couple. For example, the bride on the topper could be wearing material from the bride’s actual wedding gown. The hair color on the figure could also be changed – in one case the bride figure actually has an interchangeable plastic wig that could be changed to match the bride’s hair color. Another type of personalization might be changing the skin tone of the figures. Most of these were personalized by the bride or the baker in the years before the 1950s.[22]

The standard bride-and-groom figures may not have been accurate representations of many of the consumers who purchased them, but that didn’t prevent brides and bakers from altering them to accommodate a couple’s personal details. These alterations allowed for deviations, however small, from prescribed frameworks of the “perfect couple” in favor of illustrating an ideal tailored to the individuals to be wed.

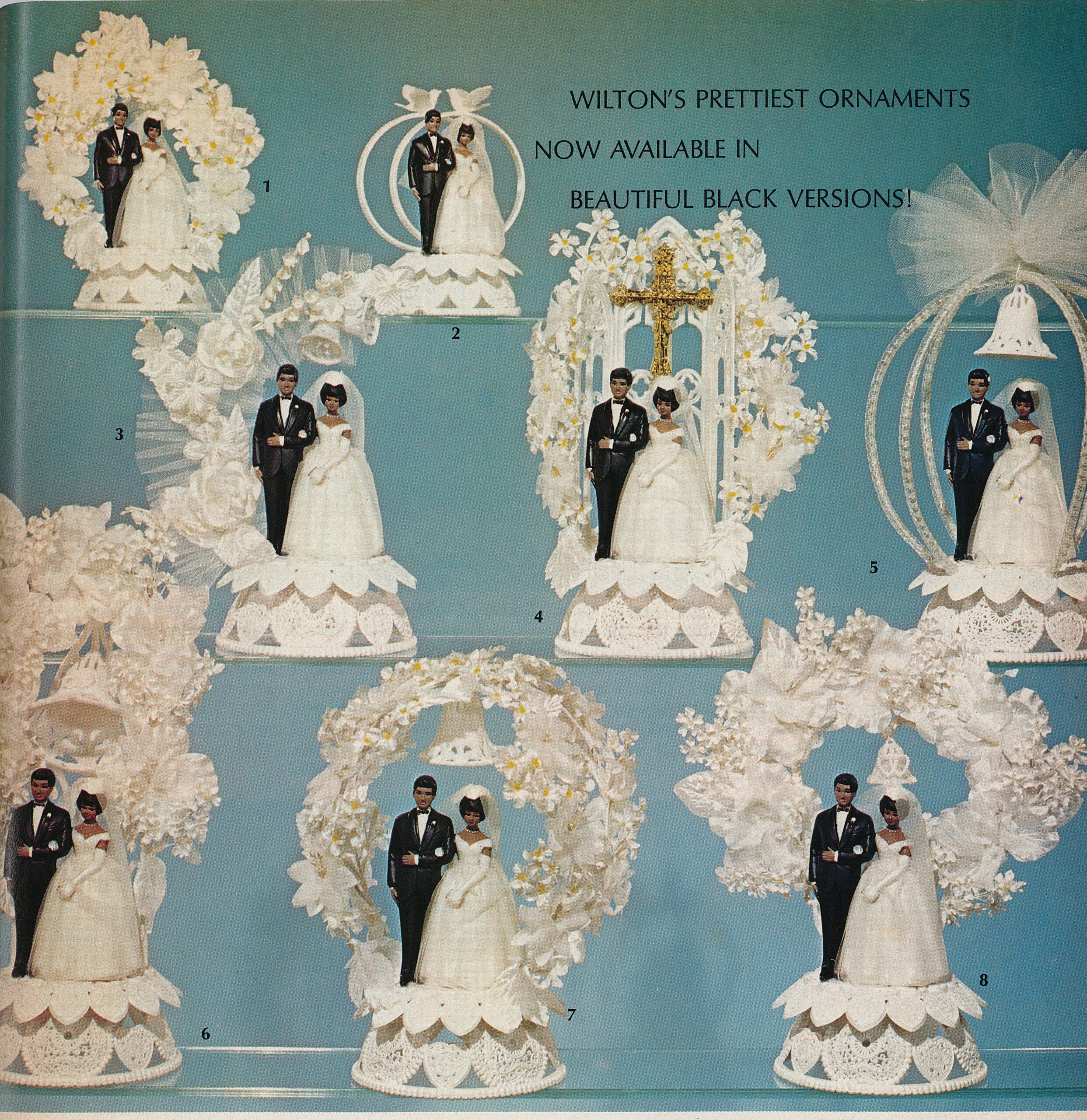

Figure 11. “Now eight of Wilton’s loveliest and most popular wedding ornaments are yours to order with black couples.” Scan from Cake & Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton: a month-by-month calendar of cake and party ideas (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises Inc., 1973), 187.

Figure 12. “Both of these figures date to the late 1940s. The figures on the left have been painted by the wedding couple or the baker, since cake toppers weren’t being mass produced with dark skin tones during this period. The figures on the right both have painted dark hair.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005),

Regarding skin tone and markers of racial or ethnic identity, Henderson indicates that mass-produced cake toppers for non-white customers weren’t widely available until after the 1950s, but some of my reference materials suggest that these were still a novelty by the 1970s.[23] This timeline somewhat coincides with the United States’ history of desegregation and the many civil rights campaigns led by Black leaders during these decades, and also reflects a market appealing to an increased Black American middle class throughout the 1960s.[24] Yet before financial incentives persuaded the wedding industry to produce non-white options for purchase en masse, individual couples and their bakers would paint readymade wedding cake toppers with otherwise unavailable skin tones.

In spite of whiteness as the presumed default, pre-1950s examples of altered cake toppers attest to alternative modes of self-representation whereby the fantasy of an ideal marriage expands. In offering only white couples, the available products signal that the dream marriage is something only for white consumers; these D.I.Y. twists contest the dominant norms of their moment and imply a yearning for something else beyond that limited scope.

Henderson identifies at least two 1940s chalkware couples “painted by the wedding couple or the baker” with dark skin tones, captioning each with “Unusual to see a personalized African-American couple in the 1940s era,” and “Unusual to find an African-American chalkware couple during this period.”[25] Henderson also lines up a set of three 1940s chalkware figures from another identical mold and notes that each has a different hair color and skin tone combination, speculating that one of the three toppers “may possibly have been painted for an Asian couple.”[26] Given that these examples are all from Henderson’s collection, they are only a small fraction of however many may have existed, and they suggest one method of stretching the boundaries of an exclusionary representative space. Another example from Henderson’s collection dating around 1970 shows a personalized composite ornament representing an interracial couple created only a few years after the Supreme Court struck down the last of the anti-miscegenation laws.

Figure 13. “Here is an example of an unpainted bride and groom cake topper.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 28.

Cosmetic changes to the physical appearance could be as simple as painting a groom’s hair blonde and adding a dark beard to the clean-shaven model. An unpainted plastic model suggests that blank couples “were made to personalize with one’s choice of color and fabric.”[27] Jeanette Michalets adds that couples would occasionally repurpose their wedding cake toppers for future anniversaries, giving the figures D.I.Y. makeovers to reflect aged appearances: “Sometimes, people created personalized couples by painting over the originals, giving the brides and grooms gray hair and painting other decorations onto the pieces.”[28] Holding onto and updating the cake topper allows for an ongoing refashioning of a couple’s vision of themselves and their world.

Cake ornaments adorned with textiles add another special touch to transform the universal one-size-fits-all abstracted cake topper into something more particular and intentionally representative. Brides swathed in pink and yellow satin wear fabric sourced from the “real” gown, indicating personal fashion but also tying the topper to the lived experience of the event. Some ornaments include additive elements of scenery; small houses with red roofs flank one couple, who tower over the buildings. Another couple stands in a large seashell grotto, surrounded by several other beach souvenirs. A different duo peers from the interior of a cast sugar egg. These supplementary environments are fanciful and strange, resituating the mass-produced figures in unexpected, personal settings.

Figure 14. “The bride and groom on the left are placed on a stand with miniature houses and a road leading up to them. I wonder if this signifies ‘Home Sweet Home.’ The couple on the right is standing in a grotto made of a shell with other shells surrounding them. One wonders if they lived on the beach or simply loved to visit there.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 26.

Figure 15. “c. 1925/1940. Probably made before II… The figures stand inside a cast sugar egg and have fabric flowers at their feet. The outside of the egg is decorated with food product roses and trim, fabric flowers, and a silver paper leaf. One-of-a kind.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 141.

These cases are just a few that illustrate the elastic possibilities of the cake topper and its significance. Each cake topper, in the shadow of a longstanding lineage of patriarchal dominance and control, can reinscribe regressive and oppressive constraints, tethering the object to entrenched traditions. But because the cake topper is mobile, flexible, and abundant in its many manifestations, it can provide glimpses of liberatory fantasies, or provocations of open-ended, imaginative play that exceeds the intentions of its origin.

Cakes marked time … Birthdays, weddings, communions, bah mitzvahs—cakes were the witnesses to our living process.

—Pat Lasch, quoted by Mara Gladstone in “Journeys of the Heart,” Pat Lasch: Journeys of the Heart (Palm Desert: Palm Springs Art Museum, 2017).

The miniature souvenir

The wedding cake topper’s ability to elicit competing sorts of fantasy—fantasies of the idealized, nostalgic model of the normative wedded life, and fantasies of a transcendent and speculative “other” that exceeds traditional norms—makes sense with its status as a miniature. Susan Stewart’s On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection explains the ways in which miniatures enable nostalgia through an infinitude of distance from an unstable or unidentifiable origin. She writes: “The miniature offers a world clearly limited in space but frozen and thereby both particularized and generalized in time—particularized in that the miniature concentrates upon the single instance and not upon the abstract rule, but generalized in that that instance comes to transcend, to stand for, a spectrum of other instances.”[29] This observation holds true for the wedding cake topper, which concentrates upon the single instance of the couple’s wedding ceremony, which comes to stand for a spectrum of other instances related to the couple, their relationship, their communities, and their values. The wedding cake topper is a materialized, encapsulated marker of an incomprehensibly large set of abstract referents tied to romance, love, and the couple’s shared lives.

Offering abundant reverie and gesturing towards possibilities that exceed categorical comprehension, the miniature is always partial and asks for supplementary narrative discourse. Accordingly, the cake topper, like other miniatures, is a site of projection: a place for speculation, fabulation, and construction of both societal norms and dreams of alterities. The miniature presents “a constant daydream” that “the world of things can open itself to reveal a secret life—indeed, to reveal a set of actions and hence a narrativity and history outside the given field of perception,” which is one way “the fantastic is in fact given ‘life’ by its miniaturization.”[30]

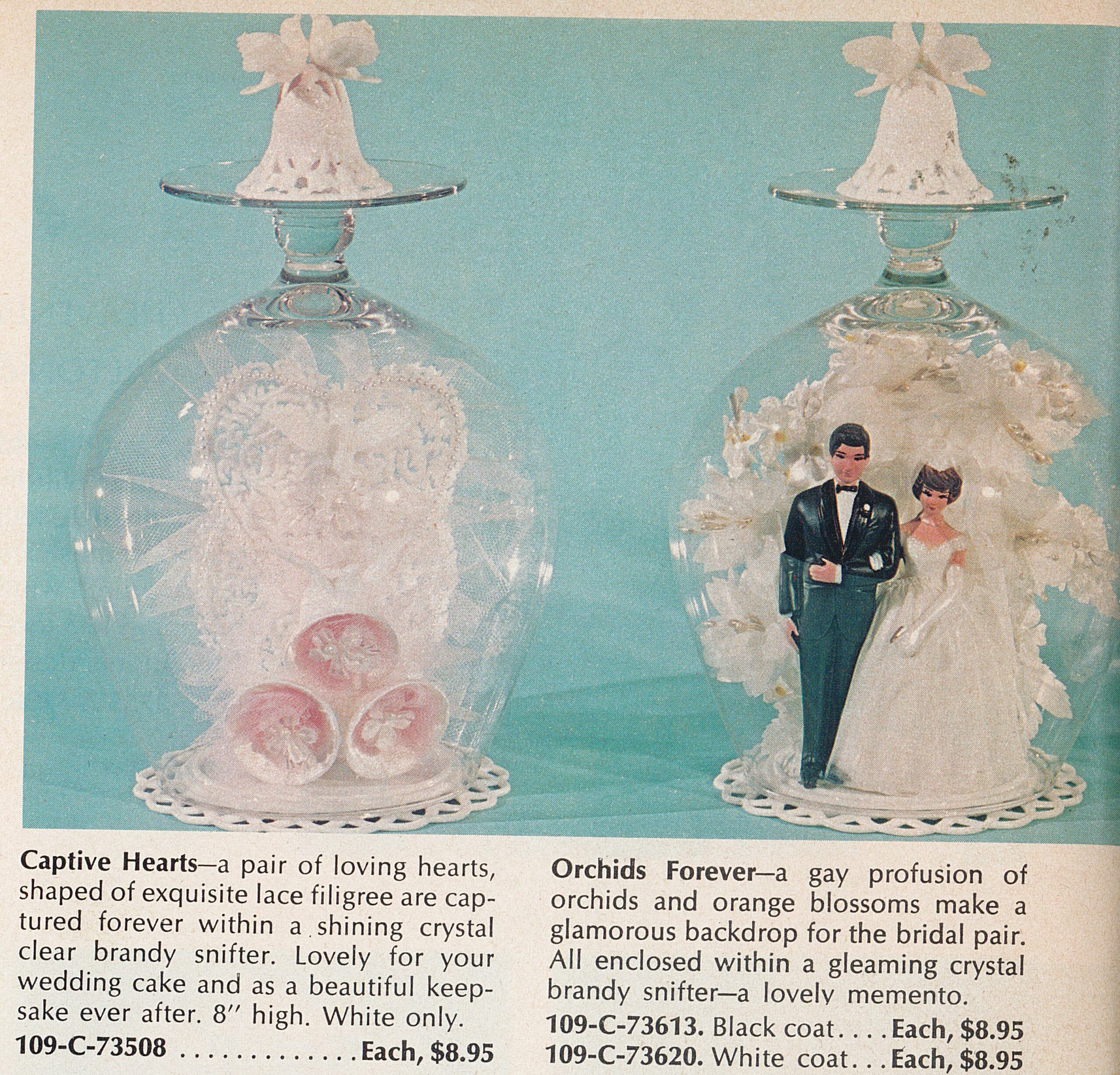

Figure 16. “Beautiful Keepsakes…Ornaments sealed in sparkling brandy snifters.” Scan from Cake & Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton: a month-by-month calendar of cake and party ideas (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises Inc., 1973), 180.

Figure 17. “Wilton’s New Dome Preserves, Displays any Petite Ornament. A charming idea from the Victorian era now revived and thriving. A sparkling crystal clear dome on a rich wood-look base displays and protects your previous wedding ornament ever after.” Scan from Cake & Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton: a month-by-month calendar of cake and party ideas (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises Inc., 1973), 183.

This capacity for fantasy does not undermine the cake topper’s referentiality to the wedding experience, though that experience itself is ephemeral. In this sense, the cake topper is both miniature and souvenir. “Within the operation of the souvenir, the sign functions not so much as object to object, but beyond this relation, metonymically, as object to event/experience. [The object is] metonymic to an increasingly abstract, and hence increasingly ‘lost,’ set of referents: the gown, the dance, the particular occasion.”[31] The souvenir reduces the context of its origin into a miniature, “a logical extension of the pressed flower, the preservation of an instant in time through a reduction of physical dimensions and a corresponding increase in significance supplied by means of narrative.”[32] So the cake topper is a sample of the now-distanced experience, which it can only evoke and resonate, but this same partiality is what enables the supplementary projections—the cake topper is “both partial to and more expansive” than its referent, which explains why they are given to mythologizing, reverie, and desire.[33]

Occupying the role of miniature and souvenir, it is no wonder that cake toppers have such strong afterlives as keepsakes, mementos, and collectibles. Within the context of families, loved ones, friends, and communities, a wedding cake topper can become itself a new origin point for narration and mythology in articulating relationships across space and time. Strangers who collect displaced wedding cake toppers narrate and mythologize too, inventing and concocting stories for their cherished tchotchkes. These collections allow for “the creation of a new context,” gathering elements to “create, by virtue of their combination, an infinite reverie,” and filling in the immediate environment with things as “a matter of ornamentation and presentation in which the interior is both a model and a projection of self-fashioning.”[34] Even separated from their initial contexts, wedding cake toppers can occasion another type of world-making and self-fashioning for the collector.

As I browse published articles on collectors of wedding cake toppers, I can’t help but notice most featured collectors are women, and their hobby is couched in the language of eccentric sentimentality, if not altogether pathologized. [35] Collecting, though inflected with consumption and capitalist notions of “ownership,” has also been a gendered pastime that allows for aesthetic curation and creativity. I think again of Meyer and Schapiro’s femmage: “Women have always collected things and saved and recycled them because leftovers yielded nourishment in new forms….Collected, saved and combined materials represented for such women acts of pride, desperation and necessity. Spiritual survival depended on the harboring of memories. Each cherished scrap of percale, muslin or chintz, each bead, each letter, each photograph, was a reminder of its place in a woman’s life, similar to an entry in a journal or a diary.”[36]

THE WEDDING CAKE OF YOUR DREAMS CAN BE YOURS… Dreams are made of cake like this!

—Wilton Book of Wedding Cakes, 1971

Projection and Play

I’ve spent this article considering earlier twentieth century cake toppers, but there are infinite sorts of these ornaments, and infinite possibilities for their deployment and contextual activation in wedding ceremonies. I barely touched upon the popularity of Kewpie wedding cake toppers, which were the first of many kinds of toy/doll-esque cake ornaments: Barbies, troll dolls, and Disney characters are just a few of countless types, which could constitute an entire article in themselves.

It’s worth mentioning that these types of toylike cake toppers further bolster the innate capacity of the ornaments to invite play, fantasy, and desire even as they uphold the social and property relations of marriage. They already operate in the zone of childlike imagination and have an innate silliness.

Figure 18. “c. 1970 to present… Hand painted detail. They are separate figures, but connect. The bride wears and organdy veil. You can just imagine the bride saying ‘Where do you think you’re going?’ as she tugs on his tails. These would be great on a groom’s cake.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 151.

Figure 19. “c. 1925/1940. Probably made before WWII,,, Groom wears a crepe paper suit and hat. He has a ball and chain around his ankle. The bride wears a cotton and lace gown and matching veil, which look homemade. She carries a fabric and ribbon bouquet in one hand and a rolling pin in the other hand. Are the planning for the future? Ouch!!!” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 145.

One of my least favorite wedding cake topper tropes is the sexist theme of an adult groom being “caught” by his domineering wife.[37] Somehow, the c. 1925/1940 Kewpie version of this concept seems a lot less disturbing: even as the tiny groom has a ball and chain around his ankle, and the bride brandishes a bowling pin, the pair feels less obvious and more open to interpretive play and storytelling.

For every contemporary wedding cake topper that rehashes the sexist and eyeroll-inducing dynamic of overbearing bride coercing reluctant groom into marriage, there is a contemporary wedding cake topper that attempts to adapt to match progressive concepts and ideologies like gender parity or queer liberation.

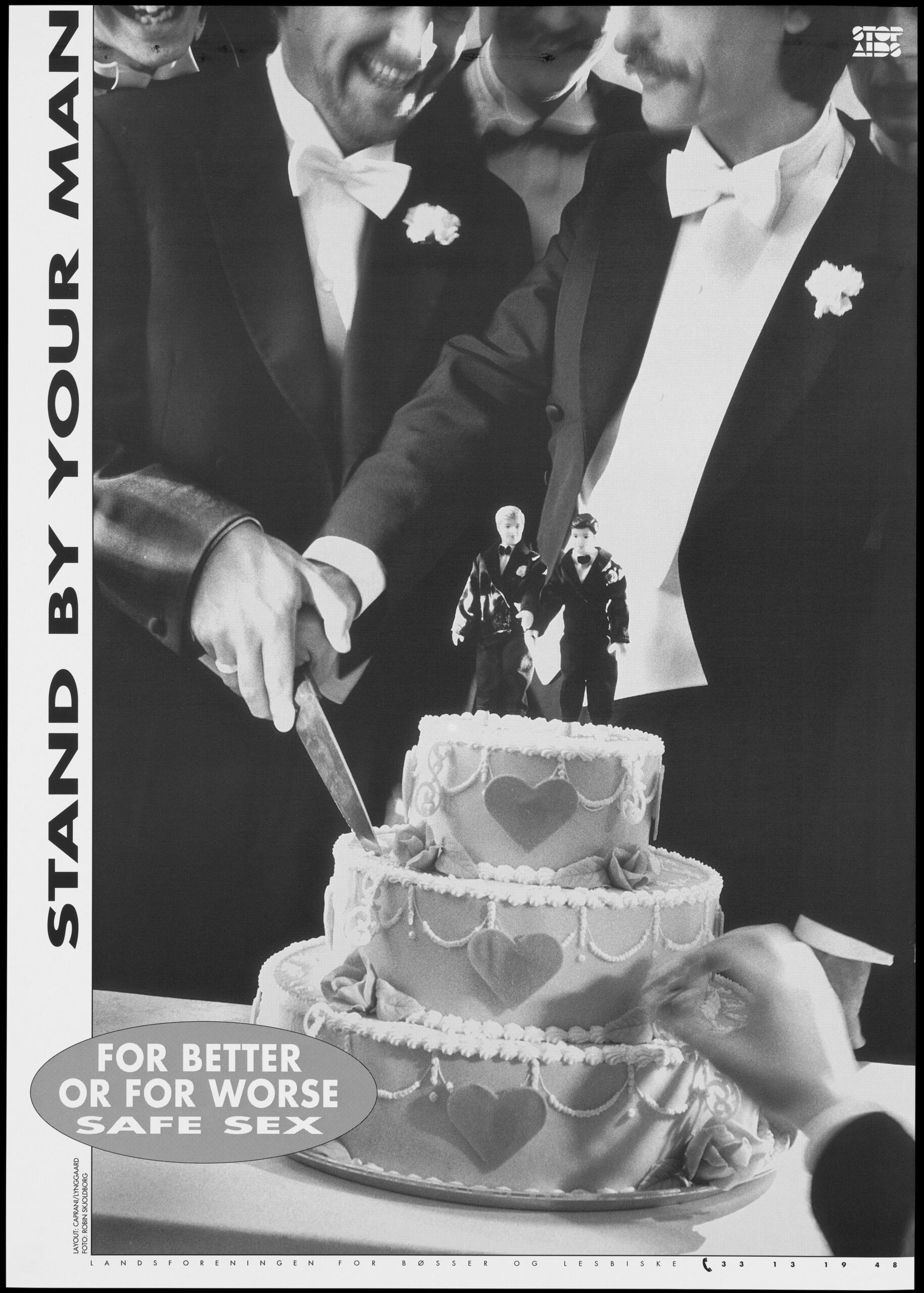

Figure 20. A Gay Couple Cutting Their Wedding Cake; a Safe Sex and AIDS Prevention Advertisement for Gay and Bisexual Men by the Landsforeningen for Bøsser Og Lesbiske. Lithograph by Robin Skjoldborg, ca. 1995. [1995?]. Lithograph ;, sheet 59.3 x 42 cm. Wellcome. (Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial)

Figure 21. Abbas. U.S.A. Texas. Dallas. 1996. After Their Holy Union (Marriage Not Recognized by the State) inside the Cathedral of Hope Which Caters for the Gay Community, Magic (Left) and Ingrid Cut Their Wedding Cake. 1996. https://jstor.org/stable/community.9 ©Abbas / Magnum Photos; Contact information: Mark Lubell, Bureau Chief, Magnum Photos, 151 West 25th Street, New York, New York 10001-7204

Two images from the mid-1990s center cake toppers in their representations of queer relationships. The caption to a c. 1995 lithograph by Robin Skjoldborg reads “A gay couple cutting their wedding cake; a safe sex and AIDS prevention advertisement for gay and bisexual men by the Landsforeningen for Bøsser og Lesbiske.” Though a Danish ad, the text on the image is in English, stating “Stand by your man for better or worse safe sex,” as two newlyweds cut their cake, topped with two miniature men in tuxedos. In a second photograph taken in 1996 in Dallas, Texas, Magic and Ingrid cut their wedding cake after their marriage, which was not recognized by the state. The photograph shows an interracial lesbian couple cutting their cake, which is topped with what appears to be a normative straight white couple. Though the topper does not physically resembled Magic and Ingrid, the brides smile with palpable joy. Both images allude to contextual crises threatening queer couples but anchor their subjects with iconographies linked to traditional marriage rites.

A 2021 children’s book, Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding tells the story of the first legal gay marriage in the United States from the perspective of two groom figurines ornamenting their cake. The animation accompanying the introductory theme to Netflix’s Grace and Frankie (2015-2022) illustrates the story of two women’s husbands falling in love through a series of vignettes of ornaments on a wedding cake, culminating in the groom figurines kissing and the brides facing away on the top tier. Both mediations utilize wedding cake toppers to simultaneously articulate convergence and divergence with expected matrimonial imagery.

Again, these many examples tie ceremonies to weddings of the past—to their traditions, to normativity, etc.—but these instances also suggest that cake toppers offer something affirming that exceeds the narrow bounds of a heteronormative origin. The possibilities embedded in the cake topper can always reinforce and reinscribe systemic structures of oppression; the cake topper is always poised to exhume traditional and restrictive histories that romanticize hierarchies of power and property. However, the possibilities of the wedding cake topper also give way to speculative alterity, fantasy, and deviance, to “something else.”

The wedding cake topper is a small but potent way to conceive of oneself in the world, one’s coupling, and what existing both within and beyond obstructive societal norms can be. Identifying creative acts in decoration and tableau-construction, as well as in the supplemental narration and mythologizing that miniatures elicit, and once more in the salvaging and recontextualizing of collecting, the cake topper acts as a site of projection and abundance, ideation, and play.

Figure 22. “c. 1970/1980… These separate figures are ducks.” Scan from Penny Henderson’s Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 153.

[1] Though cake toppers emerged during the Victorian period, wedding cake itself has a much longer history. For a detailed exploration of the creation of the wedding cake, its uses, and its meanings, see

Simon Charsley, Wedding Cakes and Cultural History (1992; repr., New York: Routledge, 2022).

[2] Penny Henderson, Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers (Atglen: Schiffler Publishing Co., 2005), 8.

[3] Henderson, 9.

[4] Henderson, 9.

[5] Charsley, Wedding Cakes, 96.

[6] Henderson, Vintage Wedding Cake Toppers, 11.

[7] Charsley, Wedding Cakes, 96.

[8] Albert Atkin, “Icon, Index, and Symbol,” The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the Language Sciences, edited by Patrick Colm Hogan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[9] Here, I am thinking of an unspoken but nevertheless instilled and interiorized system of belief that centers the monogamous, heteronormative, able-bodied, and pious couple as a sort of “habitus” as defined by Bourdieu: “the habitus could be considered as a subjective but not individual system of internalized structures, schemes of perception, conception, and action common to all members of the same group or class and constituting the precondition for all objectification and apperception…” I am also thinking of Bourdieu’s concept of doxa, whereby “every established order tends to produce … the naturalization of its own arbitrariness,” and “produce[s] objectivity … only by producing misrecognition of the limits of the cognition that they make possible, thereby founding immediate adherence, in the doxic mode, to the world of tradition experienced as a ‘natural world’ and taken for granted.” In the self-contained visual economy of the symbolic wedding cake topper, the moral superiority of a faithful, long-lasting marriage between two devout, dedicated, and fertile people is “seen as self-evident and undisputed.”

Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 86, 164.

[10] “Dove,” A Dictionary of Literary Symbols, by Michael Ferber. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

“horseshoe.” In Chambers Dictionary of the Unexplained, edited by Una McGovern. Chambers Harrap, 2007.

[11] Analyzing any of the mainstay symbolic wedding cake toppers leads to similar findings, as each component contributes to the theme of an idealized couple’s marriage: horseshoes and wishbones bestow good luck by guarding against evil fairies and devils; wedding bells drive away malicious spirits and ensure conjugal bliss; wedding bands invoke perfection and never-ending love; cherubs and cupids proffer both sensual and spiritual love while bolstering fertility.[11] Most of these traditional associations also have links with religious doctrines.

[12] There’s an article waiting to be written about the relationship between wedding cake toppers and iconic royal couples of ancient art history.

[13] Susan Stewart, On Longing : Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 133.

[14] Valerie Jaudon and Joyce Kozloff, “Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture,” Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics Vol. 2, issue 4 (Winter 1977-78): 38.-

[15] Melissa Meyer and Miriam Schapiro, “Waste Not Want Not: An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled,” Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics Vol. 2, issue 4 (Winter 1977-78), 68.

[16] Marticia Sawin, “Ceci n’est pas un gateau,” Pat Lasch : Journeys of the Heart (Palm Desert: Palm Springs Art Museum, 2017), 17.

[17] Randy Kennedy, “A 1979 Sculptures Vanishing Act: Pat Lasch’s missing artwork was not just any piece of cake,” New York Times (January 21, 2017), C1.

[18] Kennedy, C3.

[19] Julia Skelly, Radical Decadence: Excess in Contemporary Feminist Textiles and Craft (Bloomsbury, 2017), 3-4.

[20] Judith Schaechter, quoted by Jessica Marten in The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s Stained-Glass Art (Rochester: RIT Press, 2020), 15.

[21] Decorating Dissidence, accessed April 1, 2022, https://decoratingdissidence.com/.

[22] Henderson, 26

[23] This 1950s date range is corroborated by Jeanette Michalets in “Say ‘I Do’ to Wedding Cake Toppers,” Antiques & Collecting 110 no. 4 (2005): 36.; however, in a Wilton ordering catalog from 1973, a full page spread advertises “Now eight of Wilton’s loveliest and most popular wedding ornaments are yours to order with black couples,” suggesting that this choice is new for the company. See Cake and Food Decorating Year Book by Wilton (Chicago: Wilton Enterprises, 1973).

[24]Sharon M. Collins. “The Making of the Black Middle Class.” Social Problems 30, no. 4 (1983): 369–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/800108.

[25] Henderson, 27, 79, 86.

[26] Ibid., 76.

[27] Ibid., 116.

[28] Jeanette Michalets, “Say ‘I Do’ to Wedding Cake Toppers,” Antiques & Collecting 110 no. 4 (2005): 36.

[29] Stewart, 48.

[30] Ibid., 54, 60.

[31] Ibid., 136.

[32] Ibid., 137

[33] Ibid., 136.

[34] Ibid., 152, 157.

[35] Here’s a short list of articles spotlighting various divorcees, homemakers, and elderly ladies who collect wedding cake toppers:

Melissa Dribben, “’Til death do us part,’ Good Housekeeping Vol. 224, issue 6 (June 1997): 117.

Jeannie Wiley Wold, “The toppers take the cake: Collector appreciates the whimsy of vintage cake toppers,” The Courier (July 14, 2009): T2.

“The Collecting Life,” Country Living Vol. 38, Issue 2 (Feb 2015): 29.

Alix Strauss, “Collecting Treasures From Weddings Past,” New York Times (October 28, 2021).

[36] Meyer and Schapiro, 68.

[37] Claire Stewart describes this phenomenon: “Various Western figures depict a bride roping a groom or a bride with a fishing pole and a groom with a hook in his back. There appears to be a dearth of grooms casting the marriage net; yet plenty look at their watches, as the brides have left a “gone shopping” sign. Perhaps the cake-topper industry lags behind the move for female equality or actually serves as an unspoken reflection of the bridal business as a whole?” As Long As We Both Shall Eat: A History of Wedding Food and Feasts (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017), 136- 137.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.