On Intimacy: An Interview with Chloë Bass

Sara Clugage: Because this issue is called Wifey, we wanted to ask how you think about the word “wife.” Then, a corollary, does the word “wifey” mean anything to you?

Chloë Bass: The word “wifey” is part of an internet parlance that is maybe one to two degrees of separation away from me, but is not quite entering my everyday online jargon. I found the definition, which was an Urban Dictionary definition, to be one of like, “Ah, wifey is, yes, a term of endearment for one’s actual wife, but in this context is more the expectation that somebody is, like, wifing to you, without actually”—I was going to say, any of the benefits, I hesitate. “Without any expectation.”

I think answering the larger question about the idea of wife, I am somebody’s wife. Both my husband and I are vacillating on, “Are you my partner, or are you my husband? Are you my partner? Are you my wife?” It’s not something that we have been very clear on. I don’t have any problem being his wife. I don’t have any problem with him being my husband. To me, those are not terms that are indicative of any sort of normative power relations that you might assume between those roles.

In a way, I like the idea of being his wife, and I think it’s honest. When we introduce each other to other people, we’ve been very inconsistent about what we say. It’s honestly kind of awkward at times. I’ve seen a lot of pushback from friends within queer communities who are like, “How come heterosexual couples got to have partnership terms too?” I have been in queer relationships as well, so I’m not totally coming to this from the outside. I agree that the rate at which everything is reclaimed in a gender-neutral way takes the power and specificity away from it in other contexts. In a way, maybe what I want to do is state, “Yes, we are husband and wife. We are not trying to state that our relationship is otherwise because this is what it is, but also within that, it can be whatever we need it to be.”

Sara: I think that the word wifey for us crystallizes some of this ambivalence about the institution. Like, could you have a wifey and not have a wife, maybe? Although, I think for none of us does that term resonate either, which is part of why we find it so strange.

Rebecca Ariel Porte: We were particularly taken with your series, The Book of Everyday Instruction. I’m wondering if you could give us a brief summary of that project, and also a little bit about the way that you think about intimate relationships scaling up to an institutional level?

Chloë: The Book of Everyday Instruction was the second of what has been so far three, but it’s about to be four, projects that I’ve done addressing different scales of intimacy. It was preceded by a project called The Bureau of Self-Recognition, which was about intimacy between a person and themself. The Book of Everyday Instruction is a project studying pairings.Then, Obligation To Others Holds Me in My Place, which is the project I’m finishing now, is a study of intimacy at the scale of the immediate family. I’ll be starting soon, gradually, maybe I’m already casually dabbling with a project that is about intimacy in specific groups of 9 and 12. The 9 being Supreme Court justices, and the 12 being jurists. It is actually a project about law, but it’s studying the impact of that size of a group on the outsized denomination of law, both for individuals and for us as a society.

A Field Guide to [Museum] Spatial Intimacy (Workshop) from The Book of Everyday Instruction, Chapter Four: It’s amazing we don’t have more fights, 2016. Documentation from the Museum of Modern Art, photo by Manuel Molina Martagon.

Specifically, The Book of Everyday Instruction takes this idea of pairing or partnership at the one-on-one level, both as an act of two individual people, but also the pairing between a person and their city, or a person and a concept, like the idea of safety, or a person and shared work histories over time. I guess in that sense, I’m already operating at the partnership level, but also at the institutional level, because I think that there can be a kind of partnership that exists between an individual and an institution that is as fascinating, complex, tender, and fraught as the relationship between any two human beings.

Actually, Paper Monument put out a book called As Radical, as Mother, as Salad, as Shelter: what can art institutions do now? It is hilarious to me that I was asked to write for this book. I have never worked for an arts institution. Never, not one time. I still don’t. But they were like, “Write for this book.” I was like, “Okay.” At the time I was deep in Book of Everyday Instruction land, and I do come originally from a performance background. One of the roles I was occupying at that time, which really was not a performative role, but was a way of talking to or addressing people, was as a couples counselor, mediating relationships between individuals and institutions. I was leading these couples counseling workshops for individuals and institutions, and I wrote for Paper Monument in the guise of that role. I can’t tell you what you can do now, in the same way that a counselor will not tell you what you can do, but [I can] lead you through a series of steps, questions, inquiries, and observations that allows you to understand some deeper sense of yourself and the state of your relationship. Those are really fun. It feels like such a long time ago, at this point. It wasn’t. I did the last one probably in 2018 when the first round of the [Book of Everyday Instruction] show happened.

People asked me to do it subsequently, but with so many of these things that I take on, they are supposed to be temporary artworks and not permanent jobs that I can fill, in part, because I have literally no training, not even in making art objects, let alone being a couples counselor, and so it takes everything that I’ve got at any given time even to make these ideas that I’ve had in my mind come to fruition. Really, the only things I’m good at are having ideas and being myself. That has fueled a lot of the practice, but it’s very, very hard for me to wrap it up.

Sara: Those are more impressive accomplishments than most people give them credit for being, honestly. I wouldn’t be too down on them.

Chloë: Yes, I’m super swell at it. Here’s some other things I can do. I’m a pretty good cook. I’m pretty good at understanding how to get people to follow instructions, which is helpful. I’m pretty good at ignoring my plants just enough so that I’m never stressed out, but they also don’t die.

Rebecca Ariel: This is a lot of stuff for what my friend calls the invisible CV. I’m also really interested in what you’ve been saying about instructions, which seem to be a really big deal for you in the way that you approach your practice. Your poetics, if you will. It made me think about your art as being a kind of framework for a certain experience. I feel like that’s very particular to the way that you operate. Are you building some kind of framework for your viewer when you are thinking about what the piece should do? How do you think about constructing a framework, if that’s at all accurate?

Chloë: I don’t know that I’ve ever thought about it specifically in the sense of the term “framework.” I think I have thought, like, I really want to use the work to return people back to themselves, and that’s returning them back to themselves as individuals in the world, but also returning you back to yourself in the sense that you are interconnected with quite a lot of other people, places, institutions, so on and so forth. There’s a level of interrogation, presence, tenderness, disturbance that is contained within this idea of intimacy, that if you can uphold intimacy as a principle, allows you to live a bit differently than maybe you already do. Not always in good ways, but in ways that are meaningful, I hope.

It’s not as essential to me that other people are following some kind of procedural step or way of being as a way to enter into, or understand, or grow from the work, in the same way that I don’t want the work to tell people what to feel or how to feel, but I want the work to inform people to feel, right? And leaving space for that, leaving a kind of generosity and openness for that, instead of putting a fairly like—I don’t know what the word is. When people are overly explaining, what’s the word for that? I don’t want that emotional statement to be in the work, ever.

Sara: Pedantic?

Chloë: Didactic. Yes, pedantic maybe.

It’s an instructional type of work, but I don’t think there’s a solution. I’m tackling these problems for which I think there is no solution and I just have these different ways of looking at them, and I’ll do that, and whatever happens happens.

I put these words in the bathroom because the bathroom is a place where people read, from The Book of Everyday Instruction, Chapter Four: It’s amazing we don’t have more fights, 2016. Installation view from Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, photo by the artist.

Rebecca Ariel: I think by framework, what I mean is less like a maze that a mouse would run through or something, and more like you just create these conditions for us to inhabit. Certainly, it feels like there is that generosity and there is that openness in the experience. It’s fascinating, and I think really difficult, to have a form of art that gives you the space to feel intimately, and that can coexist with something like instruction, which is connected to what you do in some way.

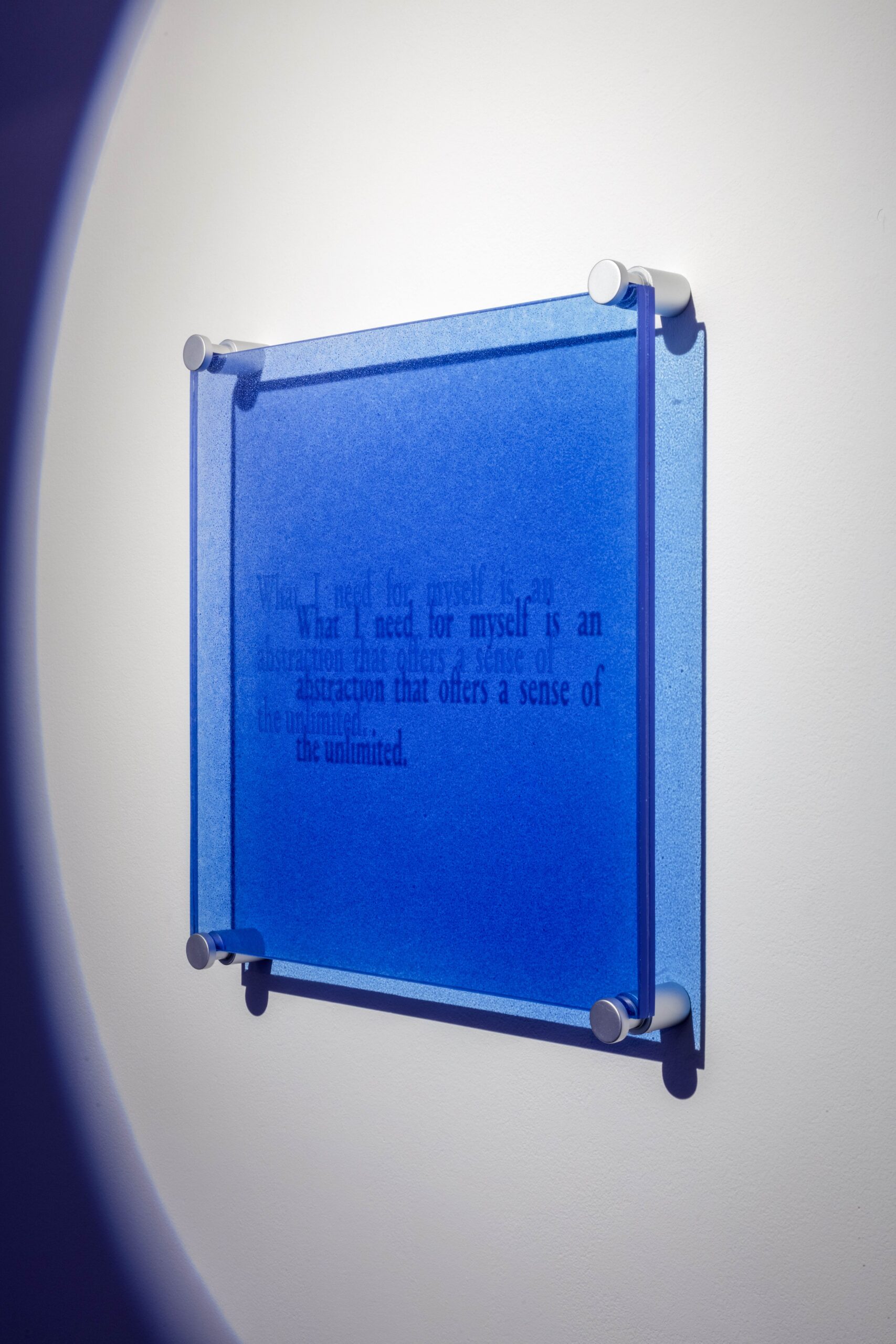

Chloë: Yes. I’m one of those idiots who’s just really compelled by the heavy, White male conceptual artworks that are just, like, a list of descriptions on a wall, and I’m so happy. I feel ashamed to be as taken in by that as I am, but I really continue to be super delighted by it and to have genuine questions like, “What if we still allowed that to stand in for art, but the people who were able to make or state those things were just different people?” That seems fine with me.

Rebecca Ariel: It’s so cool to hear you name—I guess figures like Sol LeWitt or something as influe—

Chloë: Yes, like Sol LeWitt, like Lawrence Weiner, I don’t know, I’m still into it. Yes, I’m still really into that abstraction too. My mom isn’t really active anymore as a visual artist, but she was really—when I say was, it makes it sound like she’s not alive. My mother is alive, she is not a painter or a printmaker anymore, but she was doing these abstract, minimalist, geometric color, theory-based works, and I grew up surrounded by that. I think that is a way of entertaining the instructional, as also the aesthetic. Actually, that abstraction leaves a huge amount of space for feeling. It’s just that abstract expressionists didn’t talk about it that way. That part, I really just think they were wrong, or they were right, but it was a very partial kind of rightness.

Sara: Chloë, I think what your work reveals to me is a way to inhabit really conceptual structures in a way that is warm and from the inside, in a way that maybe Sol LeWitt—that’s not a feeling I get from his work, but I’m really thinking of how much you have to be so fully present when you’re doing it. I wonder if that’s the case just to get through it, but you pay such deep attention to people, and that affords them the space to experiment or to reveal things about themselves?

Chloë: I want to pay a lot of attention to people, but I also think that actually, as a person, not as an artist, I experience really close forms of attention to be both loving and also really stressful. I’m a person who’s quite horrified by scrutiny. I’m not an extroverted person, and I am used to being able to invisibilize myself through the deep attention that I’m paying to others. It’s my coping strategy socially. There’s a lot that I don’t have to reveal about myself because I’m paying so much attention to you, and it feels so good, and so I’m protected, and you feel special. That’s great. That’s my happy place. I don’t think it’s my healthy happy place, but it is my happy place.

I want us to look more closely (Knockdown Center Intervention #1) from The Book of Everyday Instruction, 2018. Photo by Kalaija Mallery.

It’s also true that observation, we know this from a social scientific or a scientific perspective, that the act of observation changes behaviors, it changes outcomes. It becomes sort of its own character in any of those forms, whether it’s art, or science, or social science. I think in a way, that shift, that change, is not just something that I’m anticipating will occur as an outcome of a finished project, but it’s also contained within the project as I’m doing it. I just can’t always parse out exactly where it is or how it made a change.

Sara: I’m interested in what you said about being an introvert, this allows the attention to be on other people or you to be the one who is giving attention and not receiving it. I’m curious how that plays out in your choice of materials or objects. It seems to me that you choose these objects that are quite commonplace, even industrial manufactured things, like disposable napkins or stones, or like garden signs. They’re clearly not associated with your hand. They involve your words a lot of the time, but do you think that allows you to disappear into that work, to keep your audience’s attention on their own experiences?

Chloë: I think so. I hope so. The work is in a funny place right now because some of the things are like napkins, or garden markers that are made in a woman’s garage in Texas, and some of them are highly-refined, super custom processes that just look regular. I’m in a very weird place where I’ve invented accidentally three different ways of making things materially in the last three years. One, which is present in Wayfinding, like those large billboards and the mirrored double-sided signs and the photographic signs. We had to invent whole new ways of fabrication.

How much of belief is encounter? from Wayfinding. Installation view from the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2021. Photo by Alise O’Brien.

For the stone project at the Henry Art Gallery, Soft Services, the engraving was basic, but there’s also images engraved onto the stones, which are coated with the glass powder that is from the highway that makes the lines iridescent, like in the street. Getting that kind of engraving and iridescence refined, took five-ever. Now I’m working on a glass project. It’s a sundial that’s going to be installed permanently in Los Angeles. I had an idea that I was going to make a sundial and I drew it on my wall in 2017, and then was just like, “It’s that. That’s like—” When people are like, “That’s it. That’s the tweet.” I was like, “That’s it, that’s the whole project.” People were like, “That is a Post-it on a wall.” I’m like, “No, it’s a glass sundial.” They were like, “Have you ever worked in glass?” I was like, “No, but I looked up an engineering manual about sundials,” and they were like, “That is not the same.”

Installation view of Soft Services, 2022, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle. Photo by Jueqian Fang.

This year, we have been discovering that it is in fact not the same, but that what I wanted to do is doable with the creation of some new glass processes. At the same time, yes, I do want it to look like something that was always supposed to exist in exactly the way that it exists. As such, it is distanced from me. Some of the works have photographs in them that are my original photographs and that come from very close to being around me. Generally, they’re not staged. Not all, but many, most [works] have text, and that text is always written by me, and sometimes appears to be about me, but now that I’ve done like six interviews where I’ve admitted that just because it feels very personal, doesn’t mean it’s about me, I think everyone understands that there’s an element of fiction in there as well.

Rebecca Ariel: Yes, I think there has to be, right? I think about what Dickinson said about her poems, which is that they were written to be true, but they were from the perspective of a fictional person.

Chloë I didn’t know she said that actually. That’s so great.

Rebecca Ariel: Isn’t that amazing? Because it feels to me just such an accurate claim and a really useful one for those of us who don’t necessarily want to stand in the center of our work with our rib cages open all the time.

Chloë Yes, definitely. Now I’m just like taking that idea that she even said that. I did buy my mom the Fragments book, the big, beautiful Emily Dickinson little Fragments art book. [My husband and I] have the small one, but my mom got the big one. It’s just like thinking about that too, like fragmentation and the detritus of everyday life, or the scrap as a form of fictionalization is now very attractive to me.

Sara: Speaking of fictional persons, what’s your relationship to social media? You offer a lot of, I think, vulnerability on Instagram, whether true from a real place or a fictional place. I’m curious about what that scale of that audience means to you and how you see that interaction going.

Chloë: Yes. I’m curious, not in a challenging way, but I’m curious what actually you think that you know about me from the way that I am on Instagram.

Sara: I think I know things about where you are in the world. I knew when you were in LA installing. I also feel like I get a glimpse of the beats of your poetry. One thing I really love about your Instagram is how you intermix images, seemingly sometimes even banal images with really insightful phrases. It makes me think that I know something about how you observe the world. Whether I know that truly or not, I feel like I know it.

Chloë: I am actively curious. In social media, it’s always like you tend to know where I am, but only after, actually. If you think you know where I am, I’m not there anymore. I might have even been there yesterday, but I am not there now. That is self-protective, because I did face some pretty strange acts of people who thought they knew a lot about me, felt very close to me, and would show up in my life, in my actual life. They were strangers, and I will be kind and not call them stalkers, but they were edging on it, because people do feel very close to me because of the work. They think that I am really open to that in a way that is not true. I haven’t made any public statements around that, because in a way, I didn’t even want to reward it with attention.

Sara: I want to ask about the 6,960 people out of your 7,000 followers on Instagram who are not your close friends. I read in a previous interview that you cited Berthold Brecht as an influence. I wanted to ask you about theater and performance in your work and what you are performing.

Chloë: I don’t know at this point if what I am performing is one unified thing, but I think what I’m trying to do is model different ways of looking, different ways of closeness, different ways of being rewarded for looking more closely, and what it is that brings us together, even in spaces that don’t feel like they’re at all connected to anything intimate. Because I think we’ve been hoodwinked a lot by spaces that purport to be very rational and in fact, are just as emotionally irrational, maybe more emotionally irrational than my six-and-a-half-year-old. Actually, he’s been quite emotionally rational these days.

I think [that hoodwinking is] political, I think it’s structural, I think it’s spatial, I think it’s all these different things. Why I like Brecht is because with Brecht, you can be deeply embedded within the artwork and also talking about the structure at the same time. That just continues to feel relevant and interesting to me, although I don’t make plays anymore. The last play that I was supposed to make is that Wayfinding was supposed to be—I talk about it as a sculptural set for a play, but it was actually supposed to be the sculptural set for a play. The whole project was conceived and opened before the pandemic. [The exhibition] was open for six months, and then we were on lockdown, and it was still open for six more months in Harlem. That second six months, when the weather got nice, was when we were going to do the play. We didn’t do that.

The unparalleled mix of emotions, from Wayfinding. Installation view from the Studio Museum in Harlem (St. Nicholas Park), 2019. Photo by Scott Rudd.

Then, everybody was like, “Oh, it’s conceptual.” I’m like, “Well, sure.” Also, it was really the set for a real play that we never did and that we never will do. Now I’m happy with it living the way that it lives. I don’t need to tack that on. I’m happy with how certain things have changed, but I’m not totally unconvinced that theater won’t come back, which is to say, I’m mildly convinced that theater could come back into my work. One thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about, actually, is public singing with a large number of voices, although I’m not doing anything with or about that yet.

Sara: I have to tell you that when a friend and I went to visit Wayfinding, most of the picnic table area in the park was covered in the detritus of a gender reveal party.

Chloë: Ah, shit.

Sara: We spent a lot of our time imagining what that scene had just been. To us, there was a play there that we just missed.

Chloë: Exactly. There’s always a play that you just missed, or is happening around you, or that you stumble upon. I’m actually satisfied. The thing about not coming from the object-making art world is I never know how much is enough to be a show or when to stop. I was like, “I’ve never made any sculptures before in my life.” Those are the first sculptures I ever have made. I was like, “That’s not enough. These are just fine.” Studio Museum was like, “They’re very expensive, very large, very custom, very many. It’s enough.” I was like, “It has to be a play.” They were like, “Okay, we’ll do that too.” That was me really not knowing where to quit because I always think people are going to be like, “You’re not an artist.”

Rebecca Ariel: I totally understand that actually in terms of your work because you said earlier that you’re able to do some things that people with formal art training maybe aren’t able to do. There’s something to that idea that your work is actually making claims for its legitimacy that aren’t the same claims for legitimacy that other people would make with credentials. I think that that’s really inspiring actually.

I really like the idea partly because of what I do for a living, that actually there are lots of different ways apart from a formal institutional training to have an intellectual life or a creative life. I think that’s really neat.

Chloë: There’s a zillion ways, and I think like the claim for legitimacy that I’m making most often in my work is: what you experience matters. Your attention to that really matters, because all we have is that. I can never make another thing again, but still, all most of us have is that, and that is enough, and that is your whole life, and that matters. How can I make things that undergird that point, or make it more possible to live within that feeling and that reality?

Installation view of Soft Services, 2022, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle. Photo by Jueqian Fang.

Rebecca Ariel: There’s this great part at the end of Simone de Beauvoir’s memoirs, obviously a very controversial figure in many ways, but there is this one paragraph about how the thing that she’s saddest about in facing her own mortality is that all of these things that she has seen, but that make no honey, are going to be lost with her.

All these thoughts she has that are not writeable-downable or all of these sunsets that she’s seen. There is something to just being allowed to say to yourself, “Okay, if this makes no honey, then that still matters. That it can still be an important part of your life even if it doesn’t leave traces in that way. How do you encourage people to pay attention in that way?

Chloë: I’m co-teaching a class about archives, and the role of the archives specifically with socially engaged art, with Alex Juhasz at the CUNY Graduate Center this semester.

It’s a great class. Alex is a genius. I’m so in awe of her every time I speak with her. Our class has been talking a lot about the body as an archive, and the things that make no honey, they’ll appear within that archive whether they go anywhere with us or not.

Rebecca Ariel: That’s such a beautiful way of framing it. I’m really excited for those students.

Chloë: The class is so alive and so engaged and everybody is really doing their best at all times in this really exceptional way. Two of my students were like, “After this class, we go home and we can’t even sleep.”

Sara: In talking about love and institutions, I think that what you do over and over again is give people a chance to be an individual, have individual experiences, private or intimate experiences in, I want to say in a public way. I don’t mean exhibitionist. I mean in a way that other people also experience these things. I’m thinking of your plaque in [Greensboro] about the experience of being a young Black boy, or this project you’re now thinking about with the law, these things that are very personal experiences that take place (as we usually think of it) in a public sphere.

That plurality where we can all be individuals having these experiences, and they all matter, is a strong statement to make, especially to students.

Chloë: I don’t know what to say to that. Yes. Thank you. I’m trying.

Rebecca Ariel: You have this technique which we’ve touched on already of posting private-sounding speech, emotional, confessional, wondering in public spaces. We are particularly interested in the #sky #nofilter project with Instagram, or Wayfinding and the way that works in a park. Is it difficult or unexpected to have private feelings in public places?

Chloë: As a New Yorker, I don’t think so because I have 10 million neighbors and they cry and yell and kiss and do all the things in public because we don’t have enough space for stuff. For me, I’m like, “No. I’m just surrounded by people’s private experiences 100% of the time.” I find them really interesting, and sometimes I find them disturbing and I would like to cross the street or I wish to have not encountered them, but for the most part, I find them quite interesting.

Everybody’s little bubbles are bumping into each other at all times in these ways that mean something or they don’t. For me, I don’t find it that strange, but I also can recognize, especially now that I’m spending a lot of time in St. Louis, which is a city of backyard culture, you’re really not running into people and stuff in the same types of ways even when you want to. That’s, I guess, not a normal way of going through life. I just found it a wildly different experience that I can’t shed.

I knew about Jenny Holzer, but I remember the first time I saw one of Jenny Holzer’s stone benches. I was out in the sculpture garden area [of the Walker Art Center] and I found one of Jenny Holzer’s benches. I think there’s actually four where those were installed at that time. I found four benches, but I started reading one of them. I didn’t know it was a Jenny Holzer project, but I was like, “Aha. This is something I have always wanted to find. I just didn’t know about it.”

Sara: I’m curious now—I’ve been thinking of these seemingly industrial materials. Now I know some of them are very experimentally manufactured. Do you think of the words on the objects you make as defamiliarizing those materials? Are you looking for a sense of surprise in the person who encounters it as well as maybe a sense of recognition or do you think this is maybe expected territory because we know artists like Jenny Holzer?

Chloë: I don’t know, actually it’s a good question. I’ve never thought about it as necessarily a material defamiliarization process, but I think it could have that impact. I just always wonder how much regular people think about what stuff is made out of at all. You’re a craft person, which is so great and so different from me, but I think about what things are made out of all the time because I’m a compulsive observer. In that sense, I have a sense of craft, or what things could be made out of, from looking at the world. That’s how I make a lot of my decisions. Then we find out what’s possible and what’s impossible from a real making level.

I guess it’s not that advanced of an art idea anymore that something that is very ordinary materially can be also made into something that is very beautiful. I don’t know. I think also oftentimes people genuinely are confused about what these things are made out of. The medium-size text signs in Wayfinding, which are double-sided and are just sign aluminum that are mirrored and then have car frosting on them, people would walk past them and because they’re at a human scale, 24 by 36 [inches], at face level, and they thought they were screens. Because they would only see the world reflected in the lettering and not in the sign face. They were like, “How did you make those screens?” It took me a really long time to figure out what they were even talking about. What they were imagining is so much more expensive and impossible than what I had done. That was miraculous to me too.

Sara: From a luxury art object standpoint, you made something very expensive.

Chloë: Yes, I thought it was expensive in the first place. I think everything’s expensive. I’m shocked by how much things cost.

Sara: The materials you use have a maybe unobtrusive presence, or people expect to see what they expect to see in them. I want to ask about that in a performance context with your words too, or in text, do you find that people interpret your words? Do they bring it back to themselves always or do you see them thinking about other people in turn? Can you say unexpected things in a familiar way and it makes it easier to say them?

Chloë: Definitely. Yes, you can say unexpected things in a familiar way that makes it easier. You can say familiar things in an unexpected way that also makes them easier to hear or to read or to allow them to enter into your mind or your body. The answer to what do people do with it? Is it always about themselves or is it sometimes about other people? Honestly, I think that depends how they’re coming at it that day and whether they were expecting to come at it or not.

When it isn’t actual public art, a lot of the people who encounter it are not going to the place expecting to have an art experience, which is totally fine with me. Then when it’s outside, but at a museum grounds, they are expecting to have an art experience, but then also just emotionally you could see the same project five different times on five different days and have five totally different reactions based on how you were doing or what was on your mind or what you were bringing into the space that day. I think that’s fine too. I know that people have reflected experiences that they had that were deeply personal with some of the texts, but I know also people have been like, “It made me think about my mom, my sister, my kid, my loved one, my boss, my work situation, politics, whatever.” I’m like, “Yes, all of that is probably correct.” The only thing that I would say is that some of those statements that are in Wayfinding, particularly, are ambiguous in a way that I hope they can be approached by people of wildly different political beliefs, but still trend people towards my political belief.

[My belief] is that the experiences that people recount in terms of personal violence are generally real and need to be taken into account. Someone who doesn’t agree with me is not going to see ”Black Lives Matter” and do that, but they might be able to approach a sign that says, “I want to believe that bodies can be different without being threatening,” and to know something.

I want to believe that bodies can be different without being threatening, from Wayfinding. Installation view from the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2021. Photo by Alise O’Brien.

Sara: That’s actually quite an astonishingly generous position to take with respect to an audience from which you fundamentally differ politically. I love that idea, that you can incept people in a way.

I want to ask if this kind of an open-ended statement, or an ambiguity, is your approach to critique. How do you think of the relationship between your work and critique?

Chloë: I’m very unambiguous. It’s like I do these projects and then I write an essay called “Public Art as an Invitation to Abolition” where I define abolition as like, please throw away prisons right now. Thank you. It’s like I am unambiguous in it, but that doesn’t mean that the work needs to do exactly the same thing. In the same way that the work doesn’t always do the same thing as the artist. I think that there’s all these different avenues to get where you want people to go. I’m trying to offer different points of entry that make it more possible for people to really be there, while also stating my positions quite clearly, so that if and when they get there they’re aware of what I really meant.

Rebecca Ariel: I also think it’s great that the art might not have to move in lockstep with what you say about the art. You can have an account of intention that’s very unambiguous, that’s very clear. Also to allow the art to not actually be a thesis-driven argument, even if it does contain propositions. That’s a hard trick, and I admire it a lot. You’ve said so much interesting stuff about the media that you work in. How do you think about selecting media or what the right tool for the job is for a specific project?

Chloë: I think up til now, it’s usually been some combination of observation/eavesdropping as material, personal encounter, conversation, the internet, and then some kind of material I just couldn’t drop. I just get obsessed with things and I don’t know why, so then that will turn into something that is formal if at all possible or affordable.

I usually have one idea and I’m like, “It’s got to be this.” People are like, “Why?” I’m like, “The first time I pictured it, it was this,” and I’m not wriggleable on that and I don’t know why. Then we can make it better or we can’t. Like the sundial that I drew on my wall in 2017, no one would touch it until last year because they were like, “You are a crazy person. This doesn’t make any sense. Yes, we know you read an engineering PDF on the internet, good job. We’re not spending money to make this crazy thing.”

Then somebody said, “Sure.” Because now I seem to have this track record of understanding how to get a crazy thing from a bad Adobe Illustrator picture that I put together with a photograph I took in real life and some line drawings that I’ve made on my screen, and turning that into something that can live outside for two years and travel the country. Now, I will admit it takes a huge team of people to get from my bad Illustrator drawing to a project like Wayfinding, or the sundial or the rock project in Seattle.

Sara: I wanted to ask you, is there a word that does for you what “wifey” is doing for us right now, which is crystallize the problem, allow you to see how emotion and institution and politics are all entangled with us. I’m wondering if that word is “abolition” or if you have another word.

Chloë: I think actually intimacy is the word. Like when people are like, “What do you mean by intimacy?” Then they’re excited and they’re like, “It’s about sex.” I’m like, “If you look real close, there’s some sexy work in there, but not much.” I think it is intimacy because when I talk about it, I talk about it without value judgment. I don’t talk about it as inherently good or bad. I have talked openly about how slavery was a very intimate institution. How I don’t think policing itself is intimate, but some of the encounters that people have bodily with police are very intimate in really not good ways.

A Glossary of Proximity Verbs, from The Book of Everyday Instruction, Chapter Four: It’s amazing we don’t have more fights, 2016. Installation view from The Kitchen, photo by Naima Green.

Also the family, a family, is not inherently good or bad either. I could become a family abolitionist, potentially. I’m up for it. Even though I’m really happy in my family, I don’t think that it structurally works well, and certainly right now in the United States of America it is not working well. Both in terms of what it causes people to do—that it’s unkind to others because they don’t care beyond the bounds of their own family—and also the lack of familial support in the sense of just labor and childcare and housework and all this other stuff.

I think intimacy is the word for me. Wifey, that points at a lot of different intertwined complex series of interactions that are meaningful but hard to pinpoint. In the way that wifey, I don’t want to say abstracts from wife, but vagueifies wife. That intimacy is both wife and wifey simultaneously. It is specific and constantly vagueifying itself. I’m so sorry that I made up the word vagueifying.

We live in a very uncertain world. I don’t think that marriage offers certainty in terms of how your day-to-day, or even short-term, relationship will go with a person. If you agree that you’re going to remain married, at least you know that whatever it is, they’re going to be a part of it somehow and that is interesting. That is a way of thinking beyond yourself. I like being married, but I also understand that there’s a zillion other ways to create that same feeling of connectedness or futurity and this is just one way of thinking through it.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.