Documenting Detainment: The Carceral Design of ICE’s National Detainee Handbook

Usually, after a prolonged and disorienting period of travel arranged by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), migrants[1] arrive at a detention center and begin intake. It starts with a series of signatures on consent forms, searches, inventorying of personal property, and the collection and listing of any legal and identity documents into A-Files. Medical, criminal, and gang-affiliation screenings are administered. During intake, the now so-called “detainees”[2] are also issued sheets, a pillowcase and blanket, personal care items, color-coded clothing based on classification level, and the National Detainee Handbook. This handbook, received by everyone amid a dizzying series of fourteen intake steps, matters. Its production and distribution history is implicated in the state’s reproduction of violence.

The National Detainee Handbook has been standardized and is intended to provide those detained with general rules, regulations, policies, and procedures. The handbook’s language and design appear straightforward: a Q&A format, bulleted lists, infographic tables, and photographs of whitewashed spaces. Its purpose, though, is nefarious: perpetuating nationalist discourse and supporting the profiteering detention industry. Like most procedures in carceral settings, the handbook’s distribution is meant to orient, providing an understanding of rights and responsibilities. But as a part of a system of detainment, these objects produce an uneven distribution of disorientation, to riff on Sara Ahmed.[3] Following the handbook’s editorial history, we see how it is part of the “connective tissues entangling immigrant detention with the carceral state.”[4] The handbook, like migrant incarceration itself, triangulates criminal law enforcement, immigration bureaucracies, and private industry.

In this essay, I will draw from critical media and carceral studies to trace how handbooks expand and consolidate enforcement—a fact spectacularized in detention centers. The seemingly innocuous handbook performs an “epistemic practice” where “knowing is all wrapped up with showing, and showing wrapped up with knowing,” as Lisa Gitelman argues.[5] Handbooks, a recognizable mode of documenting foreclosure of rights and responsibilities, become a mechanism to assert authority and avoid accountability. With attention to the carceral logics of detainment, I will pair readings of state documents with a reflection on the documentary photographer and artist Pablo Allison’s Detainee Handbook. Imitating a state handbook, Allison’s visual project moves beyond the restrictive forms of the state’s episteme to challenge migration enforcement’s very ontology and materiality.

Detention and Plenary Power

My research focuses on the media’s role in what a growing group of border abolitionists[6] refers to as the border-industrial complex, which, like the prison-industrial complex, is a materially constituted network of government and private industries that use border securitization, detainment, and deportation as “solutions” to political, social, and economic issues.

Immigration enforcement, as a part of the border-industrial complex, is a racializing enterprise. Asylum policies, immigration quota systems, and migrant deportability are interrelated race-making practices. [7] Detention draws from these histories of controlling “nonwhite noncitizen mobility.”[8] Demographically, nearly ninety percent of the people incarcerated by ICE are from Mexico and Central America.[9] Throughout the 1990s, legislation like the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) and the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) increased the scope of mandatory detention, established minimum daily detention numbers, and lowered the bar for deportable offenses. These criminalizing policies—central to the carceral state’s expansion—are coupled with the ongoing racial-capitalist exploitation and dispossession that continue to impact migrating people from the Global South and undocumented migrants in the US. From the deterrence strategies waged against Nigerian migrants at Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) facilities in the early 2000s[10] to the indefinite incarceration of people at offshore facilities like Guantanamo Bay following 9/11,[11] US borders are enforced in the nation’s interior and externalized to imperialist encampments.

Today, ICE’s detention system continues to accrue power over legal or unauthorized noncitizens detained in their facilities. Sixteen hundred pages of recently declassified inspection reports, covering more than two dozen facilities across sixteen states, discuss unsafe conditions, absent medical care, sexual abuse, and negligent actions.[12] Reports like these, along with the enduring testimonies of formerly or currently detained people, reveal how migrant detention, as Pablo Allison said, “looks, smells, and tastes like a prison.”[13]

Though ICE frames detention centers as purportedly non-punitive, detained migrants experience the detention system as what Latina/o Studies scholar David Manuel Hernández calls the “carceral shadows.” So-called “noncitizens” are “a part of the prison system spatially, but they are also apart from the system legally.”[14] Thus, detention facilities are places where we see, architecturally and materially, the state’s plenary power doctrine made manifest. This doctrine, emerging from the history of Chinese exclusion laws, permits the federal government’s unfettered authority in cases related to immigration and creates a rights-denying framework. Recently, the doctrine was used to deny certain detained migrants the right to a bail bond hearing, grievances, or legal counsel. In 2018, the Jennings v. Rodriguez ruling determined that detained people do not have a statutory right to bond hearings, denying them due process—a decision that bolstered the federal government’s plenary power, solidifying its purview over migrant detention.[16]

The Aesthetics of Banality

The National Detainee Handbook provides insight into the big business of detention. Like a palimpsest on which the white supremacist logics of incarceration practices are traced and retraced, its manufacture tells a tale of scaled-up detention. Critical media studies literature suggests that documents, like the handbook, should be understood not by what they are composed of but by what they do. In the words of Gitelman, documents perform a “knowing-showing” function.[17] Bureaucratizing institutions, like immigration enforcement, rely on digital and paper-based documents as evidentiary records intended to maintain or avert responsibility. Even though the handbook appears to standardize operations, detention centers operate in the “carceral shadows,” where treatment, conditions, access, and care are “neither legally enforceable nor universally applied.”[18]

“Detention Standards” issued in September of 2000 for any facility holding people for more than seventy-two hours require that detained people receive a “site-specific detainee handbook.” The handbook is meant to list expectations that the facility will “advise every detainee to become familiar with” and follow.[19] At the time, each facility was responsible for printing its own detainee handbook based on the template provided by INS. The mission statement is nondescript:

The Service Processing Center or INS contract facility at [Insert Facility Location] is a detention facility of the United States Immigration & Naturalization Service. The mission of the Service Processing Center or INS contract facility is to provide a facility that is safe, clean, and sanitary for detainees waiting for processing of their administrative hearing.[20]

Similar to this example, the boilerplate language throughout the handbook is redundant in its verbiage and non-specific in its discussion of protocols.

With the eventual formalization of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2002, the oversight of migrant detention and handbook development was taken over by ICE, which moved away from the template form. Through this formalization, it demanded a different type of knowing. Detained migrants are granted only partial knowledge of the facility—no maps, diagrams, or spatially orienting images, just fabricated visuals. Like the original template form with a wall of text, the redesign repeatedly defers responsibility and places the onus on the detained person through an aesthetic of banality. This comes to stand in for understanding.

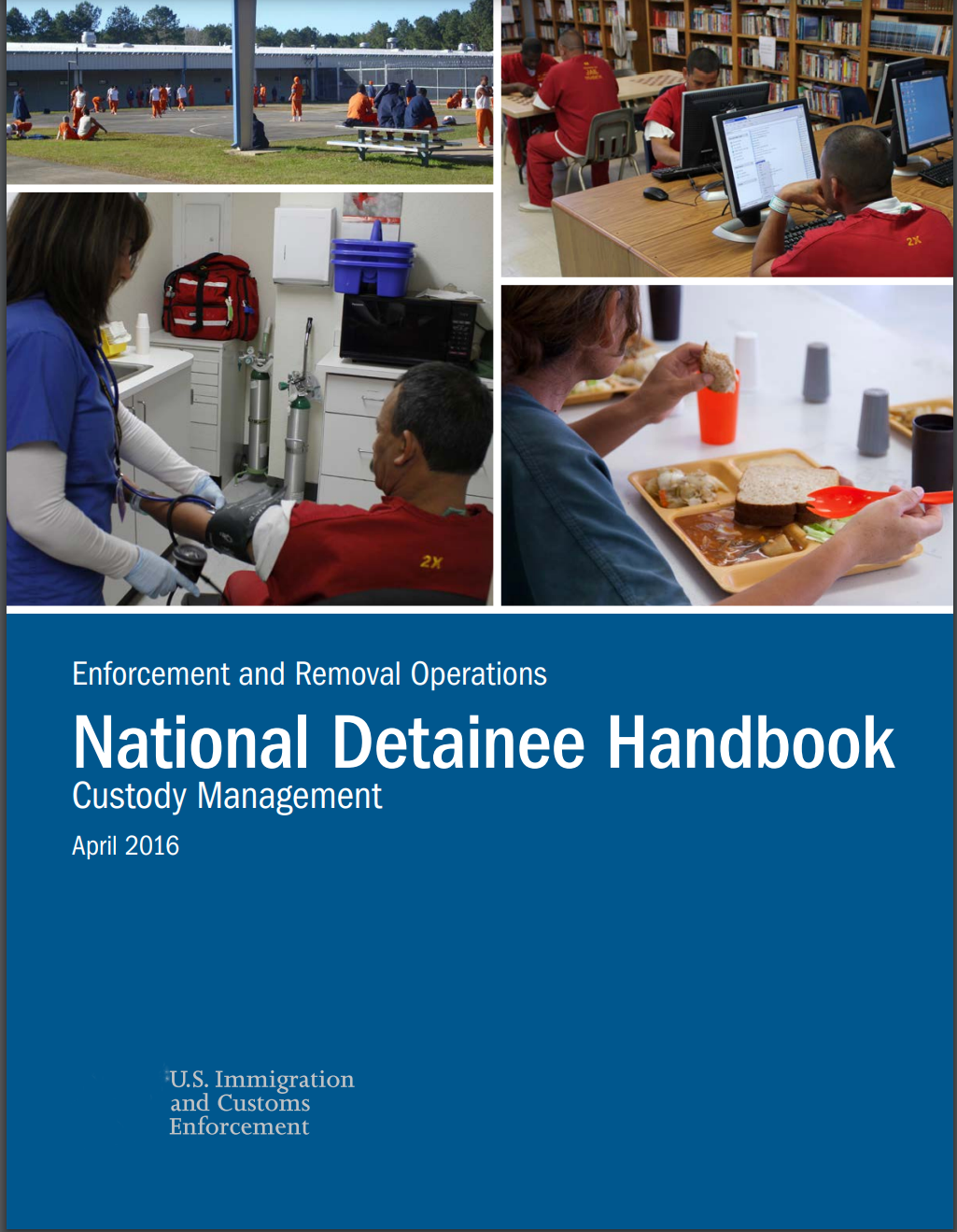

Photographs in the handbook stage an ethics of care [see Fig. 1]. The people depicted in the photographs are turned away, or their faces are blurred, meant to protect their identity, but a choice that speaks to the erasure happening across these institutions through state protocols of redaction. Throughout the book, oblique angles and hurried framing make them feel like snapshot photographs, conveying little aesthetic ambition, suggesting they are only recording what happens inside ICE’s detention centers. The handbook’s 2016 cover displays photos of several anonymized people in a detention facility. Some of these images, and ones throughout the handbook, are taken of people in the now-closed Musick Detention in Irvine, California.[21] These photographs occupy the top half, while the book’s title, DHS seal, and production details are on the lower half. The four photos, each of varying dimensions, emphasize state-facilitated care and access for the person engaging with this handbook: medical attention, nutrition, and resources for play, rest, and research. In one photo, a group of detained people walks about a caged yard; the one below it shows someone having a blood pressure reading; the photograph at right shows people at computers researching and others playing chess in the background of a library; and a fourth photo depicts a person eating food from a tray with a bright orange utensil. The photographs, with their anonymized groups and “clean” facilities, further obscure the inaccess to actual care for people in these facilities.

The cover’s banality is echoed in the additional services near the back of the handbook. The haunting statement reads:

It is normal to feel emotions like sadness, depression, anxiety, nervousness, anger, and fear in this environment. It is also normal to have problems sleeping. Try to remember that you will not be in detention forever. Think about ways to keep busy, stay calm, and stay healthy. Read, talk to people, play a game, exercise, go to religious activities, or practice relaxation techniques. A medical provider can give you information on stress management.[22]

The striking paragraph, normalizing depression and anxiety, does not account for the alarming number of detained people on suicide watch—25.7% of deaths in ICE facilities due to suicide, a figure made more chilling by an increasing overall medical death rate during the Covid-19 pandemic.[23]

Knowledge of detention is also acquired through variegated typography. Bolding and capitalization are mixed with occasional red boxes or color-coded words to highlight information. However, amid these designs are bulleted lists that prefigure punishment. Platitudes and generic photographs hide important information in plain sight. “YOUR RESPONSIBILITIES AND RIGHTS” does just that. It states, “One of your main responsibilities is to learn and follow all the facility’s rules, regulations, and instructions. If you do not follow the facility’s rules, you may be subject to discipline. You also must respect the staff, other detainees, and all property and keep yourself and your surroundings clear.”[24] The opening emphasizes that the detained person must learn everything themselves within this disorientating space. Disciplinary procedures, too, are consistently invoked even though deportation and detention are “not considered punishments for crimes.”[25] And “respect,” emphasized in the final sentence, limits the kinds of protest possible in response to the sometimes deadly conditions.

Detained people are responsible for “cooperating with the staff; using staff members’ titles, as in, mister, miss, doctor, officer, and their last name.” There is no corollary for the detained people, who are often called derogatory or racist slurs by detention center staff.[26] Nevertheless, each point in the handbook demands civil discourse, enforcing a racialized hierarchy between staff and detained people within a violent institution. The section titled in bold and all caps, “YOUR RIGHTS,” describes that “detainees” have the right to maintain “well-being, hygiene, and health care,” a right to “practice” one’s faith, “file a complaint,” and “access” resources. While these call on detained people to act for rights, others, which rely on more passive constructions, note that detained people have a right “to be provided with aids or services” that would help accommodate a disability, “to be protected from mistreatment,” and to “be free from being discriminated against.”[27] Yet, these rights are qualified through the nefarious expression that they are maintained so long as they do not “disrupt the order and security of the facility.” These qualified rights make it such that detained people have no standing or ground within this carceral machine.

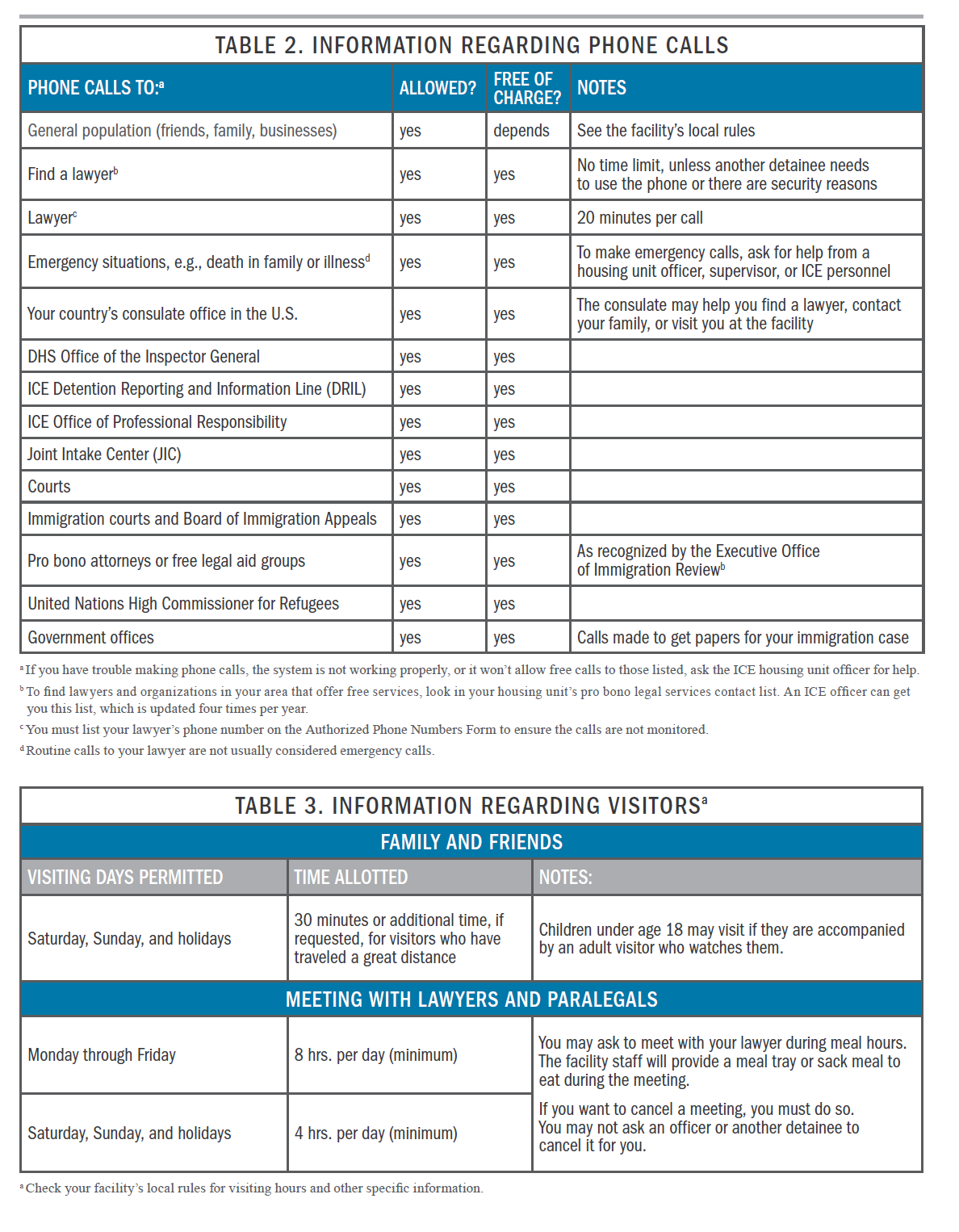

The handbook’s informative tables [see Fig. 2] help us see what Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star remind us about infrastructure, that systems are “layered, tangled, and textured; they interact to form an ecology as well as a flat set of compatibilities.”[28] Those physical things are built into the environment, seeming to be just how it has always been. The architecture of detention, for instance, with its panoptic layout or incorporation into repurposed prisons, depicts the decisions normalizing human caging and mass incarceration. Sizes of cells, bedding, sheets, access to materials, and all of these elements matter within the detention facility and are defined by various classification standards. Massive amounts of decision-making processes channeled through legal and governmental systems culminate in a table that succinctly describes the phone calls that are free and allowed and those that are not. Communication, a fundamental human need, is sold at a premium. “Practical politics” leads to decisions around what “will be visible or invisible within the system”[29]—inflecting what detained people can say, write, and wear.

Other subsections, like “dress and grooming,” detail the classification level or “security level” of detained people. The color code—blue for “low custody,” orange for “medium custody,” and red for “high custody”—is entangled in what Ana Muñiz calls a “borderland circuitry.” That is, the patterns or “circuits” of connection between local, federal, and border policing agencies who share information from surveillance programs to target racialized and criminalized people. Automated algorithms and databases classify a person going through the intake process and “erase the organization’s history of abuse and legitimize the enterprise of immigration enforcement as a race-neutral enterprise.”[30] these automated decisions, ICE officers can override classifications based on their perceptions of risks. In addition to agents’ biases inflecting decisions, the tracking, surveillance, and data collection system within this “borderland circuitry” yoke criminality to nationality and race, based on even the likelihood of gang affiliations. Status accorded, only briefly noted in the handbook, is always already ascribed—shirking the rights detained people are purportedly afforded.

Numbers related to the handbook’s production express a story of detention’s proliferation in light of these racializing regimes of criminalization. 2019 government bids on the printing of handbooks show increased detainment rates. The request[31] asked for 290,000 copies, with 120,000 in English, 150,000 in Spanish, 5,000 in Hindi, 5,000 in Chinese, 5,000 in Portuguese, and 5,000 in Arabic. The bid also clarifies that the handbook production aligns with JCP A240 printing standards, which stipulate paper, composition, ink quality, and type based on the 2011 US Government Paper Specifications.[32] It details that the handbook is supposed to be a matte-coated offset book, a material intended to make it more durable as it is held, passed out, and preserved. Handbooks, or manuals, are never really objects meant to be poured over repeatedly. One skims and moves quickly over the material, knowing it’s a reference, led by the state’s design choices. The printing office’s other specifications include stock type, thickness, and gloss. These speak to the smoothness of the paper used, indicating a lack of porosity that can withstand oil penetration for “200 seconds on either side of the sheet” with uniform coating and a clear, evidentiary notion of cleanliness. With these printing requirements, ICE illustrates the violent intimacies of incarceration. The book’s texture works at a scale where to feel it is to “always, immediately, and de facto to be immersed in the field of active narrative hypothesizing, testing, and reunderstanding of how physical properties act and are acted upon over time,”[33] to borrow Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s words. Within the material is a history of sedimented choices, like those the government has taken to increase the number of beds for detained people and construct new detention centers throughout the US. The people who touch the handbook might ask: How did it come to look like this? Why does it feel this way? And what does it do?

Counter-Documents and Contesting Rights and Responsibilities

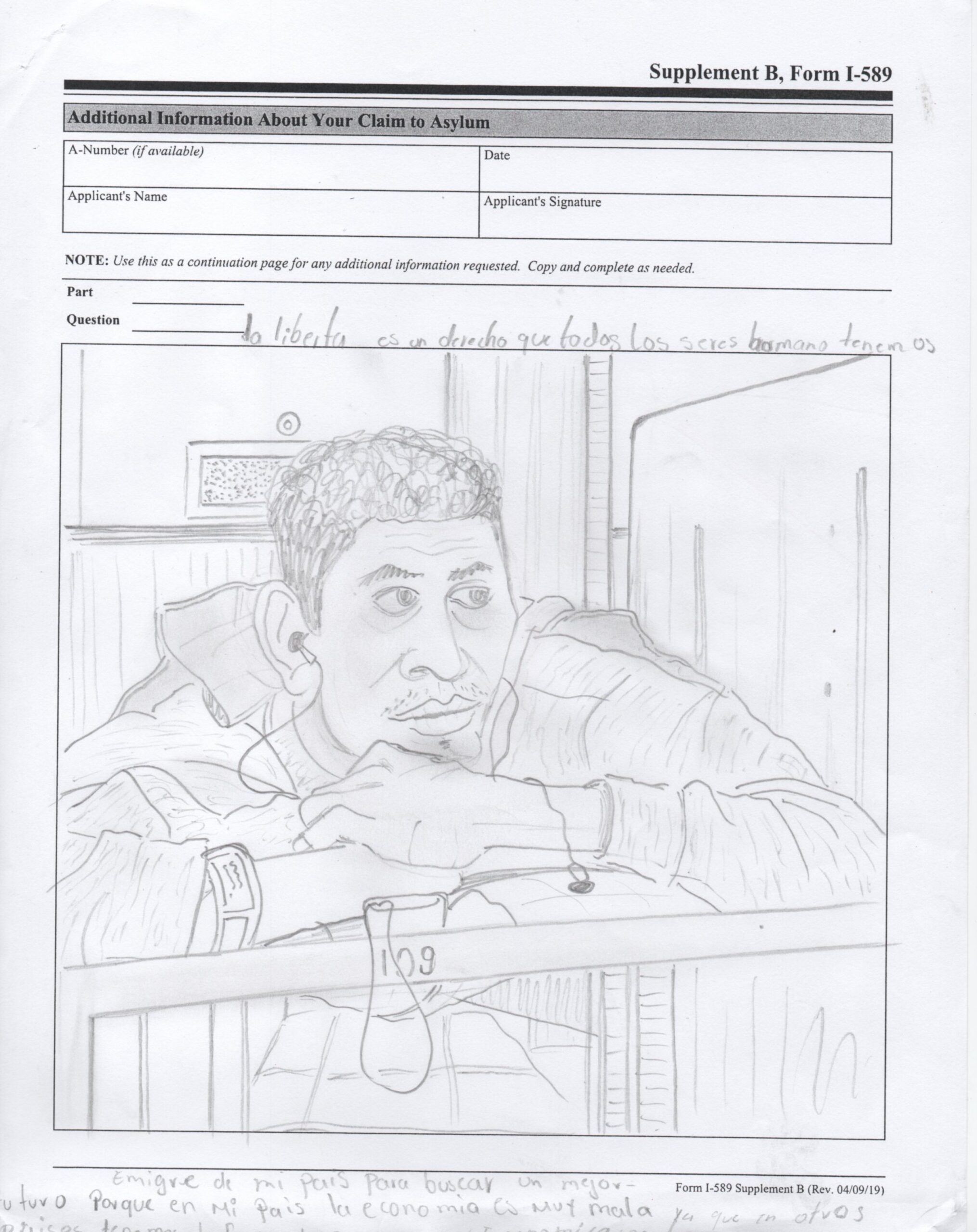

Pablo Allison was detained in GEO Group’s Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) for a month, and as he said, it allowed him to document a “side of the story” of migration he thought he would never have access to.[34] His resulting work, Detainee Handbook, refashions pages from NWDC’s supplemental information and ICE’s nationally circulated edition to attune readers to detention’s epistemic violence. He scrawls over the legalese of immigration applications with testimonies and portraits, exhibiting what Nicole Fleetwood describes as “carceral aesthetics.” [35] “Carceral aesthetics,” as Fleetwood discusses, is the “production of art under conditions of unfreedom” wherein incarcerated people use “penal space, time, and matter” to challenge aesthetic traditions maligning certain perspectives, like those of incarcerated people.[36]Allison’s Detainee Handbook visualizes detention, exhibits its temporalities and routines, and draws upon its material conditions to challenge captivity and bring its violence out of obscurity.

The cover emulates an authorized handbook. Demarked with the GEO Group logographic on the bottom left and a photograph at the top right, it looks and feels like a state-issued guide. On closer inspection, the logo for the GEO Group (a publicly traded and transnational company that works with the detention and security apparatus)[37] and the title have been shifted—a move Allison made to avoid the potential of copyright infringement—and Allison’s cover image departs from the visuals on ICE’s 2016 edition. With this sleight of hand, he expresses how the private and governmental sit together. The repurposed photograph on Allison’s cover [see Fig. 3] shows an American flag that flies vertically, cutting the image at center right, with two unadorned poles on either side. A manicured grassy lawn, bushes, and flowers are in the photograph’s immediate foreground with a vibrant intensity, making it appear touched up; a building sits at the top of the image displaying a brown-bricked façade, white walls, and a gray slanted roof; and in the background, we see chain-linked fencing and a vast blue sky. Formulaic in its representation of governmentality and bureaucracy, the image could be a branch of any institution. The only sign of detainment is the fencing barely pictured in the backdrop.

The orientation and size of the photograph on the cover belies the dramatic increase in size and bed capacity in detention centers, accomplished through repurposed and newly-built facilities, over the last few years—with average daily populations reaching nearly thirty thousand in April of 2023. To find the photo’s origin, I conducted a reverse image search and was confronted by countless images invoking the same visual tropes. We see what Teju Cole, drawing Vittorio Imbriani’s theories, describes as “Google’s macchia.”[38] The “macchia,” translated from Italian as a “stain,” creates an imprint upon the eye that expresses an image’s core or pictorial idea. Photographs, like this one and the massive archive it conjured up, algorithmically reveal the infrastructures that hegemonically constrain detention’s visuality. The carceral state relies on these standardized images devoid of detail that could be from anywhere in the US to represent the system as politically neutral and quotidian. But the white space surrounding this photograph becomes interruptive and quiet, wherein we are asked to contemplate how implicated these centers are within the border-industrial complex. Their violence, like the handbook’s, hides in plain sight.

A page missing from Allison’s work is the “Language Identification Guide,” or I Speak resource, provided by the Department of Homeland Security Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL). Alphabetized from Amharic to Zulu with fifty-nine languages represented, it succinctly highlights the transnational reach of US bordering regimes. Allison, instead, writes the names of countries over the handbook’s table of contents: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras—a few repeated. His pen attends to the racializing regime of ICE, wherein certain national groups disproportionately populate the detention center or are held there for longer average periods.

The Detainee Handbook stages refusal at every turn. Immediately following the table of contents, we are given a testimony, Soñar en Detención [Dreaming in Detention], written by Saul N. on lined paper. Saul’s handwritten testimony describes the routines of detention, feelings of resilience, and a desire for freedom. Within this claustrophobic atmosphere where “el tiempo no pasa [time freezes],”[39] Saul’s words reframe the language of rights and responsibilities. He refuses to normalize his emotional state, saying that his “mente se resiste a aceptar esta realidad [mind has resisted to accept this reality].”[40]Allison then takes us through sketches depicting the detention center’s standardized beds, bed numbers, and people at rest. Each one discloses a moment of the humanity so frequently foreclosed from view in the state handbook’s visualizations. We are reminded, through the repeated images of people listening to headphones or sitting around, of the suspended temporality of detention where time freezes. Reorienting and reinterpreting the social character of detained people highlights the effort or intentional action that keeps them in place, a force that “folds through the relational dialecticism of (im)mobility.”[41]The event of waiting engenders a relation to the world, where mobility and immobility work in rhythm. Confinement and suspension produce these subjectivities through subjugation.

Allison pushes for documentation of the humanity and agency of those people who have been detained. So he takes up what Fleetwood discusses as a “penal matter”: Detainee Request Forms and other legal applications. This legal material becomes a negative on which he sketches the detained migrants’ photographs. By using these forms to more expansively address needs and requests that their formal constraints do not allow, Allison’s portraiture becomes a kind of request or grievance against the state. Taking each of these portraits out of the facility, renders theselatent images visible andexposes detention’s conditions.

Allison’s portrait of Gilson [see Fig. 4] is produced over an I-589 form, a sheet requesting supplemental information related to an application for an asylum claim and withholding of removal. Gilson’s words read: “Lo liberta es un derecho que todos los seres humanos tenemos [Freedom is a right that all human beings have].”[42] In the portrait, Gilson’s arms, with a wristband above the right hand, are entwined, with his chin resting on them. A number, 109, is visible on the bed’s railing, and an earbud sits in his ear as he looks off in the distance. Gilson’s words demand freedom. His earbuds, hushing the sounds of incarceration around him, emphasize his desire for liberty. To the right of Gilson’s portrait is a page taken from the NWDC’s supplement to the National Detainee Handbook. There are details about extractive labor practices and the commissary at the facility: goods can be purchased at extortive prices, and detained people can work for “$1.00 per day for completed assignments.” The portrait and Gilson’s language on the bottom justify his migration to the US, stating, “la economia es muy mala [the economy is very bad].” Gilson unsettles the notion of asylum and demands attention to the violence of deportation and detainment. His insistence on the customarily foreclosed category of “economic migrant” resists the false dichotomies around deserving and undeserving migrants undergirding the exceptionalism of refugee status. We see in Gilson’s portrait, as Gitelman argues, how documents can “never be disentangled from power—or more properly control.”[43]

Figure 4: A quote from Gilson from Honduras detained at the Detention Center of Tacoma in Washington State. ‘Freedom is a right that all human beings have. I migrated from my country to have a better future cos’ the economy back there is very bad…’ Image from the book ‘Detainee Handbook’ © Pablo Allison, 2022.

Each portrait throughout the collection photographically bears a reminder of the need for representation in these spaces. Sarah Blackwood, scholar of literature, reminds us that portraits engage in “meta-representations” or “representations of the concept of representation itself” and allow us to see how they do not just “reflect or record, but rather craft new frames, new structures, through which subjectivity comes into focus.” [44] Though each one is sketched, Allison insightfully maintains that because he is a photographer without a camera, these are photos documenting the realities of the space. His portraiture relies on these tactics to reframe, restructure, and record the handbook’s immobilizing and virulent histories. How we think about representing those within spaces of incarceration is predicated on disrupting the aesthetic value systems of photographic portraiture. The portraits Allison crafts subvert the criminalizing indexes so frequently conjoined to the repressive functions of portraiture. As I have argued elsewhere, the ethics of exposure in photography are fraught. Nevertheless, it is at this moment that Allison invests in a process unsettling the state’s monopoly over visuals of detainment through a relational practice.[45] He enfolds viewers into the geographies and experiences of carcerality by attending to the handbook’s ephemerality and banality—his refusal matters.

“Documents,” as the historian Susan Pearson writes in her study of the birth certificate, “are how individuals interface with institutions, and documentation is how institutions rule.” And documentation taxonomizes and hierarchizes. Inherent within these racializing modes are determinations of who or what counts. Each of the legal, banal, and composite documents that Allison takes up and writes over recreates and subverts the imperial categories, maintaining the fabric of detention. We need experimental and documentary poetics, like Allison’s Detainee Handbook, to move us toward counter-documentation where we might, in the words of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, “unlearn documents.”[46]

[1] I use the term migrant or detained people rather than immigrant or noncitizen except when citing to legal language to draw attention to the diverse populations detained in detention facilities. In US facilities, there are asylum seekers, undocumented people, visitors who have allegedly violated visa regulations, and permanent residents who have committed what are deemed deportable acts.

[2] Generally, “detainment” is used to refer to civil detention practices used by the US, while “incarceration” describes confinement experienced by sentenced people who have been convicted of a crime. These distinctions have been clarified by Department of Justice in its 1999 Annual Accountability Report, here.

[3] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

[4] David Manuel Hernández, “Carceral Shadows Entangled Lineages and Technologies of Migrant Detention,” in Caging Borders and Carceral Statement: Incarceration, Immigrant Detentions, and Resistance, ed. Robert Chase (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 79.

[5] Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge : Toward a Media History of Documents (Durham, Duke University Press, 2014), 2.

[6] Of note is Naomi Paik’s work, which calls for an abolitionist approach to sanctuary that attends to borders’ role in the “interlocking forces that criminalize differently marginalized people (via citizenship status, race, gender, etc.) and the interlocking need for a broad-based movement that empowers all targeted people.” Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First Century (Berkley: University of California Press), 5. Similarly, Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke De Noronha’s recently published Against Borders: The Case for Abolition insists border are obsolete and argues border abolition should be “planetary in scope.” Against Borders: The Case for Abolition (New York: Verso Books).

[7] See Lisa Marie Cacho, Social Death: Racialized Rightlessness and the Criminalization of the Unprotected (New York: New York University Press, 2012); Stephanie DeGooyer, Before Borders: A Legal and Literary History of Naturalization (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022); and Kevin Kenny, The Problem of Immigration in a Slaveholding Republic: Policing Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2023).

[8] David Manuel Hernández, “Surrogates and Subcontractors: Flexibility and Obscurity in U.S. Immigrant Detention,” Critical Ethnic Studies: A Reader, ed. Critical Ethnic Studies Editorial Collective, Nada Elia, David M. Hernández, Jodi Kim, Shana L. Redmond, Dylan Rodríguez, Sarita Echavez See (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016): 305.

[9] Emily Ryo and Ian Peacock, “The Landscape of Immigration Detention in the United States,” American Immigration Council, 2018. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/the_landscape_of_immigration_detention_in_the_united_states.pdf

[10] See Mark Dow, American Gulag (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

[11] See, for instance, Naomi Paik’s Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in U.S. Prison Camps since World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

[12] Tom Dreisbach, “Government’s own experts found ‘barbaric’ and ‘negligent’ conditions in ICE detention,” NPR, August 16, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/08/16/1190767610/ice-detention-immigration-government-inspectors-barbaric-negligent-conditions

[13] Laura Barrón-López, “Photographer documents immigration and life inside detention facility,” interview with Pablo Allison, PBS NewsHour, October 18, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/photographer-documents-immigration-and-life-inside-detention-facility

[14] Hernández, “Carceral Shadows,” 58.

[16] For a discussion of this case’s implications, see “Jennings V. Rodriguez.” Harvard Law Review 132, no. 1 (2018): 417–426.

[17] Gitelman, Paper Knowledge.

[18] “Immigrant Detainees Petition Homeland Security to Issue Enforceable, Comprehensive Immigration Detention Standards,” National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guide, press release, January 25, 2007.

[19] Immigration and Naturalization Services, National Detention Standards, 2000. The 2000 NDS is available at: https://www.ice.gov/detention-standards/2000

[20] Immigration and Naturalization Services, “Detainee Handbook,” September 20, 2000.

[21] Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS) databases show several of these shots in B-roll footage of the Musick Detention Facility in Irvine, California. Ron Rogers footage what we see on the cover, imitates the angles of recordings of common and recreation areas, housing and medical care units, library and dining hall. Ron Rogers, Musick Detention Facility, B-Roll, https://www.dvidshub.net/video/137253/musick-detention-facility

[22] National Detainee Handbook, 2016, 25.

[23] See Sophie Terp et al., “Deaths in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention: FY2018-2020,” AIMS Public Health 8, no 1 (2021): 81-89.

[24] National Detainee Handbook, 2016, 4.

[25] Hernández, “Carceral Shadows,” 84.

[26] Corrections Expert’s Report on Orange County Jail, November 15, 2017. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23814493/4-orange-county.pdf

[27] National Detainee Handbook, 2016, 4.

[28] Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things Out : Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), 38.

[29] Bowker and Star, Sorting Things Out, 44.

[30] Ana Muñiz, Borderland Circuitry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022), 25.

[31] Bid request, 2016 National Detainee Handbook, April 29, 2019.

[32] See Government Paper Specification here.

[33] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 13.

[34] Allison in Barrón-López, “Photographer documents immigration and life inside detention facility.”

[35] Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), 25.

[36] Fleetwood, Marking Time, 25.

[37] Notably, GEO Group has run the deadliest ICE detention facilities. See Detention Watch Network, “Third Death in Immigration Detention Makes the Adelanto Detention Center the Deadliest Facility in 2017,” June 6, 2017, https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/pressroom/releases/2017/third-death-immigration-detention-makes-adelanto-detention-center-deadliest

[38] Teju Cole, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021).

[39] Detainee Handbook, 10.

[40] Detainee Handbook, 9.

[41] David Bissell, “Animating Suspension: Waiting for Mobilities,” Mobilities 2, no. 2 (2007), 278.

[42] Allison, Detainee Handbook, 18.

[43] Gitelman, Paper Knowledge, 5.

[44] Sarah Blackwood, The Portrait’s Subject : Inventing Inner Life in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 5.

[45] Benjamin Williams. “‘His Eyes Disappear’: (Re)framing the Racial Imagination through Anti-Portraiture in Teju Cole’s Blind Spot.” ASAP/Journal 8, no. 1 (2023), 93–118.

[46] Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso Books, 2019).

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.