With Lunar Calendars: On Pat Parker & Merle Woo

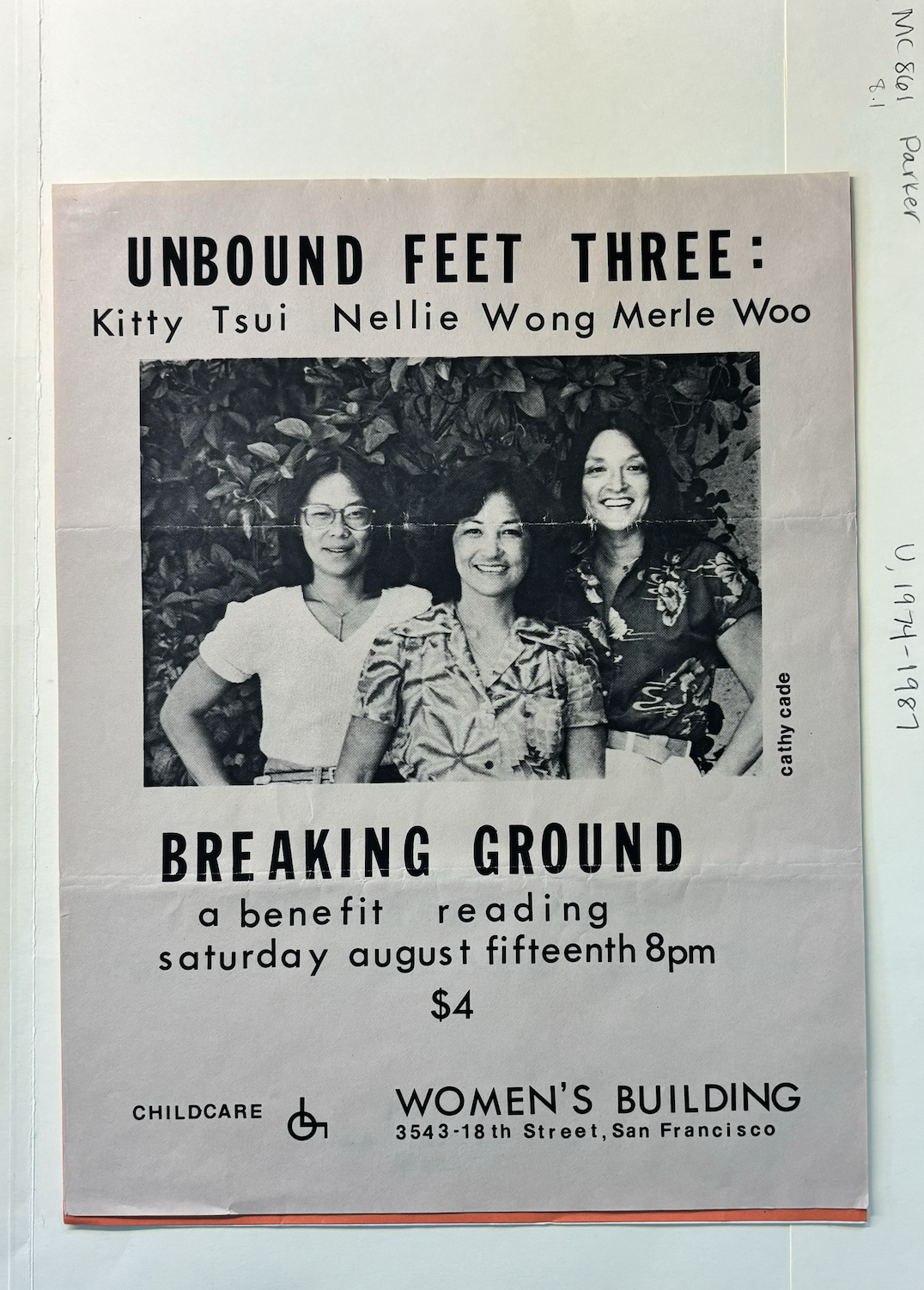

I find flyers for performance group Unbound Feet in Pat Parker’s archive and endeavor to reach out to its members to see if they might speak to me.[1] Parker kept not only the flyers of their reading series, but also newsletters distributed as the group split up. Nellie Wong, Merle Woo, and Kitty Tsui sent out newsletters that described their political position as lesbians, queer, socialist women, who wanted the group to take radical positions against the US Empire and their support of student activism. They believed their other groupmates did not share their positions, the newsletter states. The letters asked for public support of their cause.

From the Papers of Pat Parker, 1944-1998, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Photograph by the author.

I consult the internet for their whereabouts and upon realizing their independent artist status has left little web presence, I ask Shawn Wong if he knows them and if he could put me in touch with them. I ask the novelist and poet Willyce Kim. I ask scholar Dorothy Wang. I ask everyone I know.

I arrive at Nellie Wong’s residence prepared with questions and admiration. I want to learn more about Unbound Feet, her poetry, and her work as a socialist organizer. I am enamored by her energy, her commitment to revolution. She tells me about the most recent and ongoing protest efforts of her comrades. Is this what it looks to be politically committed long-term?

I ask her about poetry, about the dynamics of conflict and the possibility of resolution. I ask her how her political education took shape, and if there were deviations/ruminations throughout. She has prepared a lunch of pasta and salad, and I come with mini cakes and other desserts. I learn about her time traveling to China with Alice Walker for a socialist organizing group, her politicization in college through gender studies and literature courses, and how she has almost completed another book of poems that she hopes to self-publish.

I leave with several pamphlets and her poems. I read her poems again on my way home, and wonder about her ability to remain committed to revolution versus the many who have quietly given up. Of course, the revolution cannot be measured by the imprint of sacrifice on those with the least amount of power, those often considered colleagues and comrades: I say this every time a stranger compliments themselves for recycling glass containers or refusing plastic bags. Aggressively I ask what all this recycling will do when the oil pipeline leaks, again (and it leaks and leaks), or when they start drilling into the Pacific Ocean for cobalt. I can feel my voice cracking with anger, shrill as I pose a worn question, one I have posed before. I repeat it not to instruct or shame, but to remind myself that our individualism means nothing. That our individual actions appease nothing?

And nevertheless it hurts so much when someone quietly surrenders, doesn’t it. Does it? And those who seem naive, hysterically giving long speeches on social media platforms about sellouts and hypocrites and the better past. Versus those who have given up, cultivating theories on how their surrender and passivity is, in fact, the most radical act of all. Mirroring the desires of white flaggers, they critique the morality of morality, they critique the function of individualism and judgment, and they critique legibility and more. There is nothing to say, no one to chide or cheer. You hold onto your closest friends and joke about feeling surrounded, and is there a way to say this without sounding paranoid? There is no one to look up to and few to trust. Everyone is trying, paying someone else’s mortgage and recovering and trying to recover and laughing and hoping to laugh and what more can you ask of them. Can you ask anything of anyone? And if you can, what would you ask?

* * *

The flyers for Unbound Feet in Parker’s archives are marked 1981. A few years later, in 1982, in El Tecolote, Edgar Poma writes of Merle Woo’s firing by the Asian American Studies program at the University of California Berkeley.[2] He synthesizes the case:

Woo, a socialist feminist and lesbian and member of Radical Women, is well known for her strong protest of the growing conservativism in her department. She was a critic of the department’s elimination of community language programs, the steady firing of department instructors, dissolution of a student tutor program, and the discouragement of student input in decision making within the department. Woo was also a critic of Ethnic Studies’ move into the College of Letters and Science, a move which would eliminate the formation of a Third World College on campus. In her classroom, Woo incorporated a multi-issue perspective into the course curriculum, and spoke against racism, sexism, heterosexism, and class oppression.

The University cuts first from the agendas most needed by students: community language programs and direct student input into program building (are there any of these elements left at universities?). The University’s engaged dissolution of community-oriented programs speaks to the ways many of these programs were forged: direct student action and activism. Rod Ferguson demonstrates the ways in which Ethnic Studies and Gender Studies programs were created to appease and intellectualize anti-war anti-imperialist campus protests.[3] Given this fraught history, these departments and their programs will and remain under constant threat of dissolution.

What is often left under-analyzed is how the formation and weakening of these programs is performed through non-white persons. Such as, the professors charged with firing Woo are Asian American, and the professors who opposed the students were at times, not-white.[4] As Frantz Fanon remarks, the process of colonization is a collaboration between the bourgeoisie and the colonizers.[5] As in, agreements for a modicum of power are made for those who want to preserve the institution for themselves, against those who seek transformation.

Pat Parker kept news clippings and pamphlets concerning Woo’s wrongful termination lawsuit, and the case speaks to the labor politics still in place at the university, where contingent and adjunct faculty who support student critiques against austerity measures are brutally sacrificed before the university. But Woo’s story is not one of surrender. In “Our Common Enemy, Our Common Cause: Freedom Organizing in the Eighties,” a pamphlet that includes Audre Lorde’s “Apartheid U.S.A.” published by Kitchen Table and Women of Color Press, Woo writes of winning the case against her termination, being reinstated, being dismissed and then winning in arbitration. Of her efforts she writes, “I was fortunate to be reinstated just in time to participate in the explosive anti-apartheid movement that broke out on the Berkeley campus in the spring of 1985.”[6]

She describes the dynamics of anti-apartheid organizing as student-led and student-driven, writing,

We ought to look at and learn from our most militant students… because they know they will be selling themselves on the marketplace, they will be looking at the world with a keen eye. They are change, a barometer of society. Many are rebellious and radical and ‘idealistic.’ Since they have little to lose, they are the most apt to challenge authority. And what have they accomplished? Why, in 1985 they helped to bring apartheid to the attention of the world and exposed the hell out of the university system.[7]

She takes the usual insults levied at students–idealistic, radical, nothing to lose—to expose their transformative properties. Why should and how could those with the “most to lose” and the most cynical find exits from the status quo?

And the status quo, the thing that needed to change, was the 2.4 billion dollars of UC workers’ pension funds and student fees invested in South African Apartheid.[8]

It is not so surprising to learn of how Asian American activists worked with students against apartheid, and that Pat Parker was interested in these connections. And also, this is not what is advertised in liberal narrations about history or the past. Liberal narrations emphasize linear progression and insist on positivistic development. According to them, history is not a circular loop waiting to explode through connection. The students being expelled in the 1980s for engaging in antiapartheid activism and the students suspended and expelled for engaging in anti-genocide activism in 2024: What happens when they, we, they, find each other?

* * *

Woo’s writing centers the work of students and the potential for student activism. In “Three Decades of Class Struggle on Campus” she writes,

I’ve been involved in a 27-year struggle over students’ minds, hearts and bodies. Most students wanted a degree, so that they could get a decent paying job. At the same time they wanted tools to survive as whole human beings: to develop self-confidence and independence of thought. They wanted tools to change their communities. These were the students I would fight for… People who had been denied the real history of their people: the resistance, rebellion and heroism in the face of the strongest international ruling class in history.[9]

Woo clarifies a debate that continues to be stirred in informal and formal settings on the utility of an education and chasm between pragmatism and activism. She acknowledges the actualities placed on students—a degree and a decent paying job—with desires for independent life. How might education teach one to live in the material constraints of this life and also foster desires for things beyond what’s been given? Woo suggests it begins with the teaching of history as a source of power and intrigue.[10]

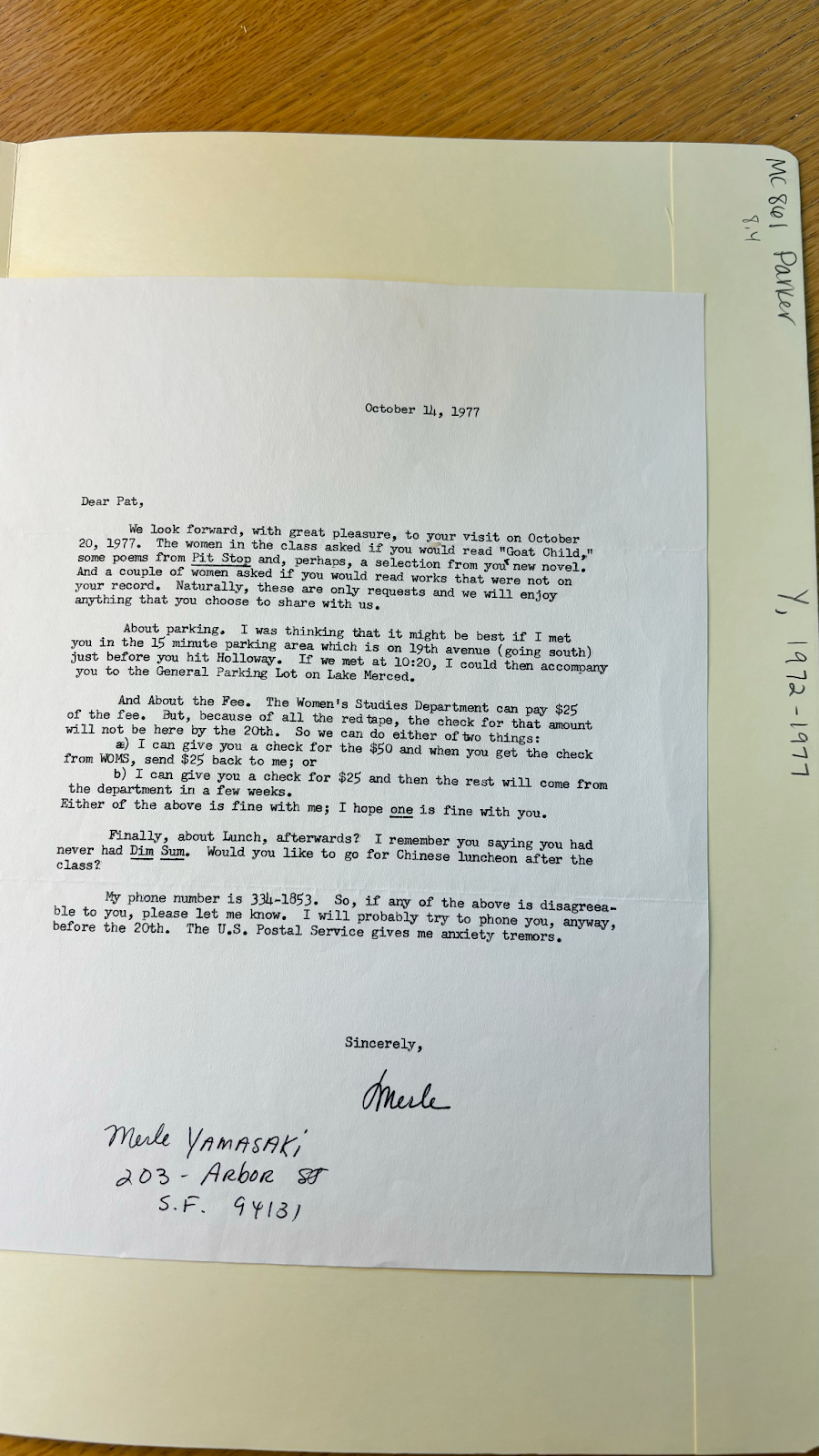

In Parker’s archives there is a letter from Merle dated October 14, 1977. The letter is about Parker’s upcoming class visit, which details parking, coordinating the honorarium, and student reading requests. “The women in the class asked if you could read ‘Goat Child,’ some poems from Pit Stop, and perhaps a selection from your new novel. And a couple of women asked if you could read works that were not on your record. Naturally, these are only requests and we will enjoy anything that you choose to share with us.”[11] The letter is written with the care of an institutional veteran who wants to demystify its policies and find amendable workarounds.

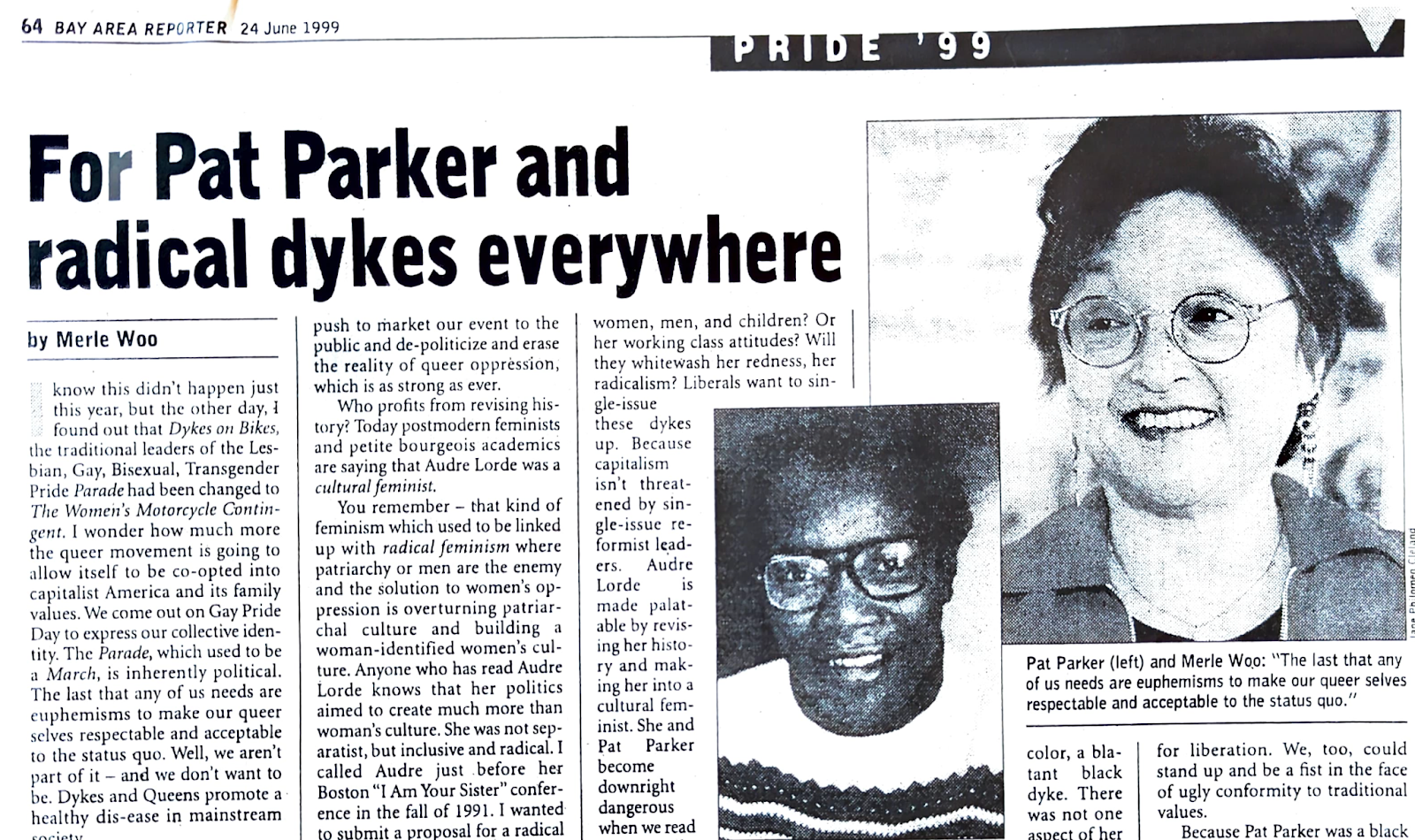

Their friendship and relationship continued throughout the decades. In an 1999 op-ed titled “For Pat Parker and Radical Dykes Everywhere,” in the Bay Area Reporter, Woo writes about Pat’s poetry, her activism, and this visit to her class.[12] Woo writes, “In 1977 I invited Pat to come talk to my class on Third World Women Writers. She was a key voice for feminism, and knew it. Her poems stunned the young students. Her love poems were not all gushy and feminine and mystiquey…Pat Parker was exploring something very new in the early 1970s. And since we haven’t had the revolution yet, I bet she has something for young queer and questioning youth today.”

From the Papers of Pat Parker, 1944-1998, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Photograph by the author.

“For Pat Parker and Radical Dykes Everywhere,” Pride ‘99 section, Bay Area Reporter, June 24, 1999, 64. From a reprint by Radical Women. Photograph by Mich Ling.

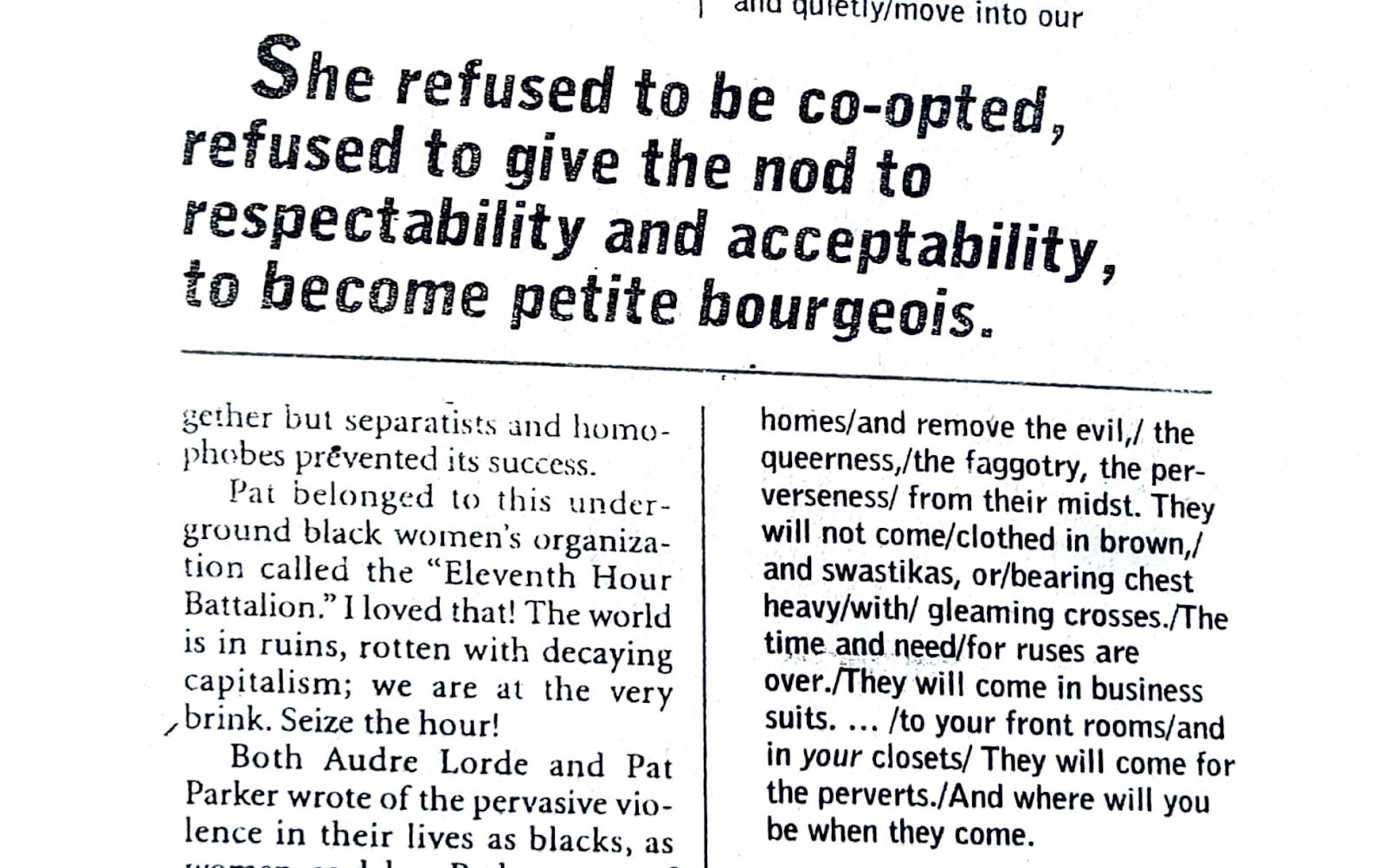

“For Pat Parker and Radical Dykes Everywhere,” Pride ‘99 section, Bay Area Reporter, June 24, 1999, 64. From a reprint by Radical Women. Photograph by Mich Ling.

As a writer, I’ve looked to Pat Parker’s work for as long as I can remember. I had a copy of her “Don’t let the Fascist Speak” taped to my writing desk throughout graduate school, and listened to her reading of the poem as often as possible. Parker’s fearless language and position became an antidote against the curative ruse of poetry and literature. And through Pat Parker’s archive I learn about the histories of third world movements: the students, the educators and the writers who would not back down.

* * *

I ask Merle Woo about campus organizing and her poetry. She tells me that students who organized against apartheid “saw what was at risk,” and then some “really took those risks” and continued a life transformed by their radical actions.[13]

The fact that the past is full of people who fought, won, fought, failed, fought and fought—the fact that the past is full of people who fought and that we don’t always know their names is a testament against the conservative thesis that history is a progression. They fought then, they watch us now. The fact that we will never know all of their names is ammunition against the tragedy of utilitarianism, a scythe against the righteousness of individualism.

Do we know that we cannot be writers unless we take the older generation with us?[14]

So you meet someone who has been fighting towards revolution their whole lives and they are young for their years. They tell you, the fight gives you life,[15]and this is a valve: a key with many questions. A determination to find others.

[1] I have written about my search for these flyers before, see https://poets.org/text/unbinding-poetic-lives

[2] Found in Parker’s archives, MC 861 Parker 8.3 The news clipping comes from the “Merle Woo Defense Committee” newsletter. Papers of Pat Parker, 1944-1998, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

[3] Ferguson writes, “In the context of the academy, how are modes of power exercised upon the daily lives of minoritized subjects and knowledges and how was that exercise prepared for in histories that are supposedly no more? … While the state governments in California and Wisconsin called out the National Guard on students advocating for ethnic studies, systems of power also responded to these protests by attempting to manage that transition, in an attempt to prevent economic, epistemological, and political crises from achieving revolutions that could redistribute social and material relations. Instead, those systems would work to ensure that these crises were recomposed back into state, capital, and academy. Whereas modes of power once disciplined difference in the universalizing names of canonicity, nationality, or economy, other operations of power were emerging that would discipline through a seemingly alternative regard for difference and through a revision of the canon, national identity, and the market.” Emphasis mine. Roderick Ferguson, The Reorder of Things (University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 28–29.

[4] This does not mean that white supremacy and antiblackness dissolve from these frameworks—this speaks to their solidification.

[5] Fanon writes, “In the colonized territories, the bourgeois caste draws its strength after independence chiefly from agreements reached with the former colonial power.” Fanon, Frantz. Tr. Constance Farrington. The Wretched of the Earth, Grove Press, 1963 (117).

[6] Audre Lorde and Merle Woo, Apartheid U.S.A.; Our Common Enemy, Our Common Cause: Freedom Organizing in the Eighties, Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press, 1986, 17.

[7] Ibid,, 21-22

[8] Woo writes, “And U.C. has the gall, the unmitigated gall in its profit mongering to invest UC workers’ pension funds and student fees in South African Apartheid to the tune of 2.4 billion dollars! U.C. backs repression from Berkeley to South Africa and we all know it.” Ibid., 16.

[9] Merle Woo, “Three Decades of Class Struggle on Campus,” in Legacy to liberation : Politics and Culture of Revolutionary of Asian Pacific America, ed. Fred Ho (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2000), 159.

[10] Merle Woo to Pat Parker, October 14, 1977, MC 861, 8.4. Papers of Pat Parker, 1944-1998, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

I take up some of these questions in a forthcoming essay on Decolonial Hacker, titled “What I Did Not Do, Changes Me.”

[11] Ibid.

[12] “For Pat Parker and Radical Dykes Everywhere,” Pride ‘99 section, Bay Area Reporter, June 24, 1999, 64. From a reprint by Radical Women. I thank Mich Ling for bringing this piece to my attention.

[13] I was able to interview Merle Woo with Emily Woo Yamasaki on August 30th, 2024. This essay would not exist without their generosity.

[14] This is a question posed by Shawn Wong to me in an interview (November 27, 2022) about his activism. The article that was informed by this interview, “Poetry for the People,” is published in the Spring-Summer 2023 issue of American Poets, https://poets.org/text/poetry-people.

[15] Merle Woo, interview with the author, August 30th, 2024.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.