Wayward Taxonomies

“Wayward Taxonomies” is an evolving conversation between three poets/friends—Christine Imperial, Sarah Yanni, and Simone Zapata—which extends from formerly unpublished interviews that Simone hosted with Christine and Sarah based on their works for the 2022 exhibition Tense Renderings: the will and won’t of spatial logics, co-curated by Simone. Conceived in the theoretical framework of Renee Gladman’s Bagley Wright Lecture, “Lines into Grasses,” Tense Renderings invited cross-disciplinary interrogations of the motivations, conditions, and limitations of maps and mapmaking.

***

Space is not a static field. It does not wait for our offerings or our movements. It is not blank and has never been blank. Spaces moan. They are of another order. –Renee Gladman, “Lines into Grasses”

Simone Zapata: The idea for Tense Renderings emerged through a series of conversations between myself and my collaborator—visual artist Fía Benitez—as part of a year-long, post-graduate residency with California Institute of the Arts. We found that much of our shared research took issue with capitalist definitions and exploitations of space, and by extension, the bodies and lived experiences within those spaces. When we expanded our consideration of cartography to include modern-day wayfinding tools such as documents, material vestiges, photographs, oral history, and even the governing forces of language itself, Tense Renderings became invested in the unlimited ways that space and its inhabitants challenge, reject, and subvert their “objective” representations.

Eager to grow our respective fields of knowledge and build community in a post-pandemic world, Tense Renderings extended this inquiry to our peers, leaving the method and direction of their interventions open to interpretation. Sarah and Christine were two of the fourteen artists featured in the exhibition, and as their practices are primarily rooted in poetry, I was intrigued by their visual adaptations of text to create an impression that language alone could not accomplish. Positioned diagonally from one another across the gallery space, Sarah’s and Christine’s pieces negotiated a shifting, disorderly subject who refuses categorization imposed by the state, family, society, and ultimately the subject themselves.

***

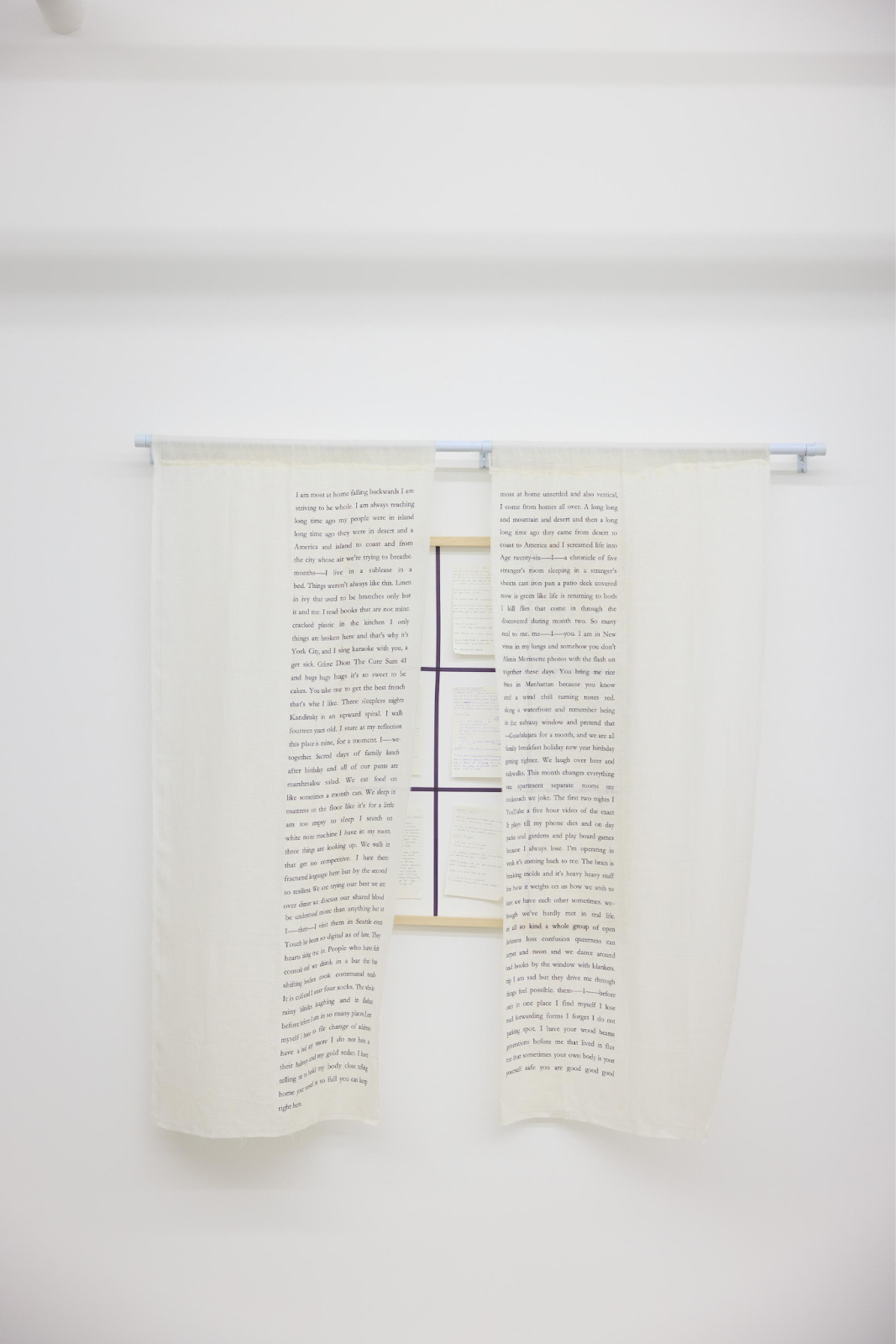

Simone Zapata: Sarah’s work, I am most at home falling backwards, is the first on display as we enter the exhibition, and from afar the installation is intuitively familiar to us: a pair of linen curtains draping a wooden-framed window—similar to what we’d find in a home or intimate space of dwelling. Coincidentally, the work is situated right beneath the gallery AC, which circulates a subtle breeze through the curtains as if the window was open, inviting the viewer to come near, to inhabit its frame of reference.

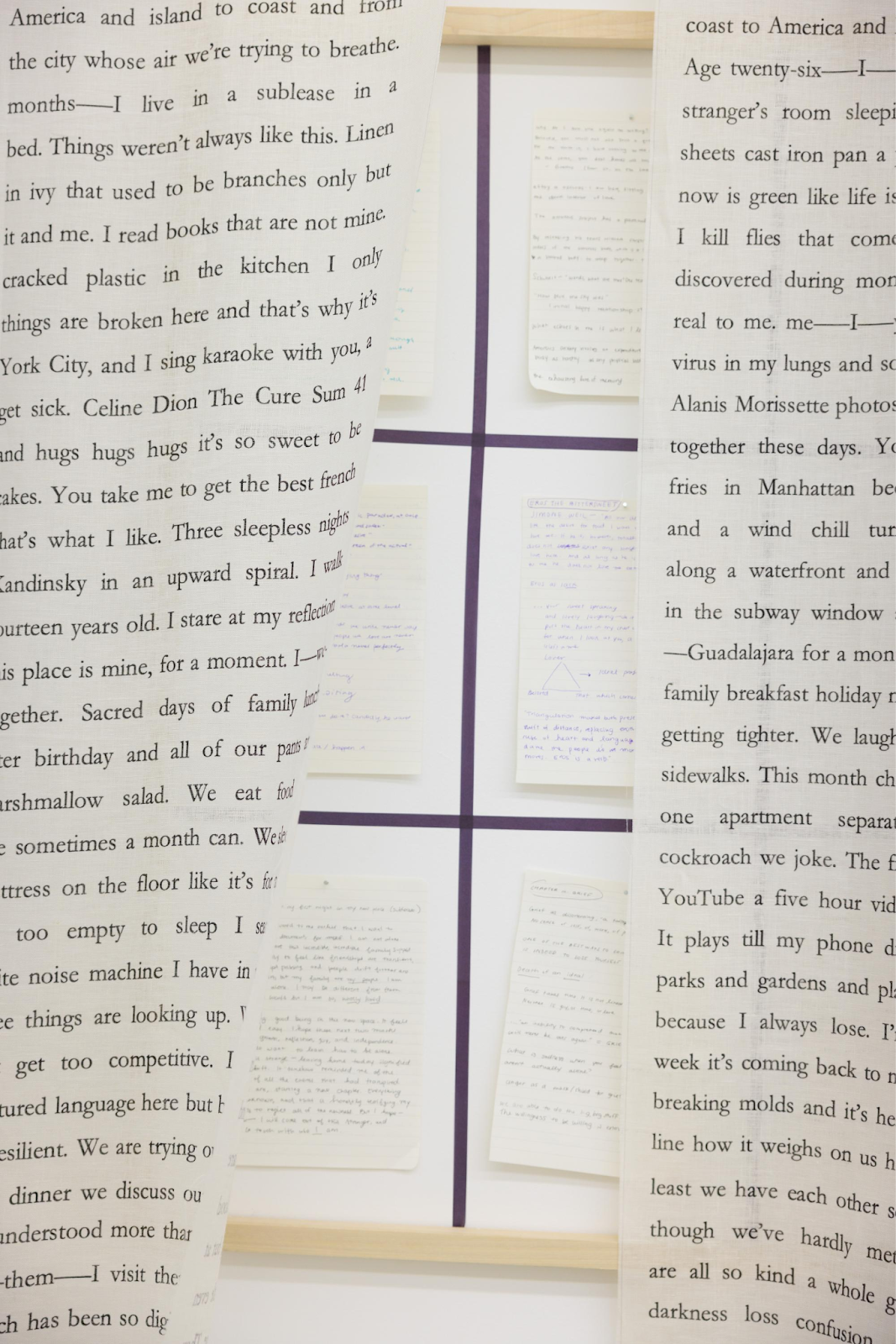

Sarah Sophia Yanni; I am most at home falling backwards (detail), 2022; Linen, metal, wood, tape, paper; 58 x 59.5 in.

Sarah Sophia Yanni; I am most at home falling backwards, 2022; Linen, metal, wood, tape, paper; 58 x 59.5 in.

In her book, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, Sara Ahmed writes that our pursuit of certain goals is so often based on the paths we’ve already taken. She says, “For a life to count as a good life, it must return the debt of its life by taking on the direction promised as social good. A queer life might be one that fails to make such gestures of return.”[1] I wonder, do you consider backwards to be a return?

Christine Imperial:

I do not notice how close I am to the wall until the curtain

drapes across my back as if I, too, were part of the work.

The language keeps moving. I fall

backwards.

Sarah Yanni: Backwards first came to me as I was thinking about non-linearity—“coming out,” as people call it; a “second adolescence.” It’s a literal sense of backwardness. You’re going through very adolescent emotions as you communicate these truths about yourself. I meant the “backwards” more generally as well; the kind of refusal to go forward in this pre-prescribed direction—

CI: It is in being disoriented

that one feels most at home,

or is it in the loss of control?

And queerness absolutely ruptured this path. The time I’m writing about in this piece is an overlap between the self and all these others that the self is colliding with, passing through different spaces. It’s a very porous you.

SZ: There’s a line on the curtain that I love: “So many things are broken here and that’s why it’s real to me”—the subject recognizing a part of themselves in another’s ruin, the deterioration of the body’s neat borders. There isn’t a clear way to navigate this accumulation of selves and spaces; what this piece offers instead is a field of awareness.

SY: Being so freakishly in touch with your emotions and feelings—you can’t coast by during times like that. You are so in it. When everything breaks apart, you’re really dropped into your life in this way you can’t evade.

CI: There’s a discomfort in letting people in.

There’s a discomfort in the voyeur

becoming participant.

SZ: The lack of glass between the viewer and the work feels intentional, too—unprotected from the elements, the viewers’ sticky fingers—a rejection of preciousness in favor of the raw and physically unfiltered.

SY: I wanted this piece to feel very tactile and intimate, like you could just put your face up to the paper and read it and touch it.

CI: In “Glazier, Glazier,” Cole Swensen writes,

“A window is always relative to a body, and

the body is never repeated. Thus proliferates.

Because every body involves a window or

windows, looking out on the world ‘at large,’

as they say, the body is not single.”[2]

I’m thinking about how we create our own homes. They’re literally something we can make; not necessarily always a “place,” but a sum of experiences that change over time. I am most at home falling backwards is not an art piece that just hangs on a wall—there’s a lot of moving parts that I spent time constructing and assembling into this particular space.

CI: How do I answer the question,

“Where do you call home?”

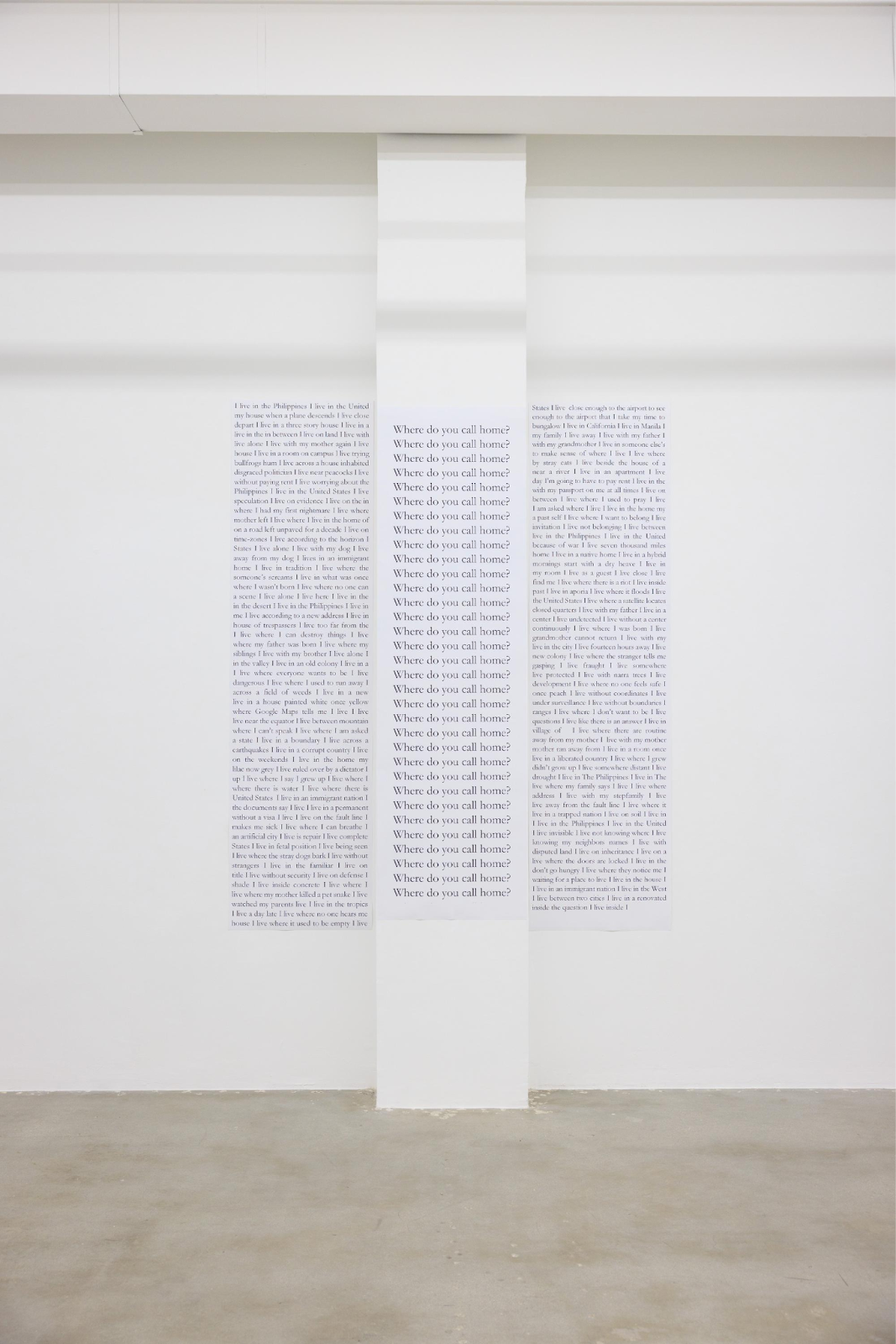

SZ: In Proof of Legal Presence, the excess and overwhelm of what this question [Where do you call home?] insinuates is palpable through its sheer scale and repetition. The title of the piece references a legal form of the same name that verifies state residency. By mounting the text on and around the gallery’s center column, the piece becomes a meta-critique of institutional infrastructure, and the way language upholds these infrastructures via state-sanctioned documents.

SY: I crane my neck up and back in order to engage

with the writing. The center column

like an incantation, surrounded by slippery

declarations: I live in the Philippines…I live in

the United States… I live where a satellite

locates me…I live fraught. The only constant

is something internal.

CI: “Where do you call home?” condenses the multitude of questions posed to ascertain one’s belonging, residence, and presence. It also indexes if one is not just physically present, but lawfully present. Rather than establishing empirical proof of belonging, what are the affective experiences of belonging? There’s also an intimacy to the question, “Where do you call home?” that isn’t present in the more obvious question of, “Where are you from?”

SY: And be sure––the world will want to clarify you.

The world will demand intimacy.

Questions of origin and belonging, especially for diasporic subjects, are never neutral. Beyond the document, questions of “Where are you from?” also show up in the everyday. In both the United States and the Philippines, when I’m asked where I’m from, I wonder if that means where do I live now, where did I spend most of my life, where did I spend the first years of my life, etc. No answer I give seems to suffice.

There’s an exhaustion to the lived experience of multiplicity and fragmentation—the hyperawareness of the self’s interminable dispersion—that is so bodily. The feeling isn’t necessarily happiness or sadness; it kind of makes you feel sick. Repetition can make you sick.

SY: But this kind of truth cannot be confined in a neat sentence.

SZ: Where did we learn this mode of invasive inquiry, and why do we feel entitled to full disclosure? Even in everyday conversation, we invoke the document by relying on its labels and checkboxes to cross-reference. If the response is insufficient, we recruit the document’s method of scrutiny by repeating the questions until some answer satisfies our expectations.

The connection between repetition and ideology is crucial here. I’m thinking about how, as kids, we learn language by tracing—we trace letters to learn their patterns, to repeat them until the patterns become unconscious, embodied to the point that we no longer need the reference.

SY: Unconscious reproduction keeps the subject

in a false calm. Rote movement, familiar tracing,

a mouth opening and uttering—

CI: Inscribing ourselves through tracing requires discipline and the repetition of discipline. You have to discipline your whole body in order to trace properly.

SY: It’s a new kind of

nausea, different from the

one that haunted us before.

SZ: We become hypervigilant of our movements—correcting our wayward lines and curves to stay within bounds, crossing our t’s, dotting our i’s. We hold ourselves personally responsible for our own legibility, employing a kind of self-surveillance to do so.

CI: Edouard Glissant writes, “Repetition, moreover, is an acknowledged form of consciousness both here and elsewhere. Relentlessly resuming something you have already said.”[3]

SY: “Repetition can make you sick—”

SZ: And yet there’s a striking juxtaposition—as much as the document’s legitimacy hinges upon relentlessness, the repetition here disintegrates its language, scatters its meaning. The phrase “Where do you call home?” is exploited to the point that even its nuance loses steam, its reference becomes moot.

SY: and so we dizzy ourselves away

from checkboxes, categories,

accepted dichotomies.

CI: The language of “I live” is always shifting, and repetition makes language sound weirder. “Where do you call home?” becomes almost a chant, transforming question to utterance.

***

CI: This is where rhythm takes hold of sense—through the simultaneous maintenance and deviation in rhythm, new meanings are produced.

SY: How do we find balance, then, moving through a nascent rhythm?

CI: Our conception of home is an act of disorientation that wrests away from being a singular place of dwelling to one where exile and embrace intertwine. For many queer people of the diaspora, our work resonates with what queer of color scholars such as Gayatri Gopinath and Chandan Reddy have articulated: that home has been—and may always be—a vexed space of ambivalence.

SY: The disorientations of language and self are both rooted in a sort of grief, but also look toward new horizons of possibility. It is exhausting to be legible within prescribed frameworks, but we poke holes within the logic of hegemony to see what else we can create.

SZ: How does your work imagine

this “you” finding their way?

To be between places forces you into the body, and that is seldom a comfortable place to be. Rather than dwell on this internal, we may be more comfortable with the external—gazing out an airplane window, surrendering to the negative capability found amongst others. Now two years out from the creation and presentation of these works, I wonder if this disorientation has lessened or shifted. Is it possible for disorientation to be ephemeral?

CI: Returning to Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology, she writes, “The temporality of orientation reminds us that orientations are effects of what we tend toward, where the ‘toward’ marks a space and time that is almost, but not quite, available in the present.”[4] Reinvigorating “toward” with “almost” requires us to be open to the inevitability of disorientation—the possibility that we might never find our way to our intended destinations.

SZ: And what exactly

would be our goal upon

arriving, anyway? Would it

make us feel complete?

SY: It’s been over a year in my same apartment, with its brown carpets and high ceilings, in the LA neighborhood where the three of us spent so much time loitering at 7-11 or drinking happy hour wine at the Cheesecake Factory. Christine and Simone have since moved up to the Bay, and each time I visit their home in West Oakland and collapse upon the air mattress they dutifully inflate for me, I fall backwards in the best way. Time moves fast and it doesn’t. In my eyes, we are always grad students, mischievous and gossiping.

[1] Sarah Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 21.

[2] Cole Swensen, “Glazier, Glazier,” in The Glass Age (Farmington, Me: Alice James Books, 2007), 62.

[3] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). 45.

[4] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, second printing (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). 20.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.