Florine and the Three Worlds

We are the sunbursts

We turn rain

Into diamond fringes

Black clouds

Into pink tulle

And sparrows

Into birds of Paradise

Florine Stettheimer, ca. 1916

A curse that besets women artists—and women in general—is the irreconcilable binary. Sometimes a binary appears in its most classic forms, like the virgin-vixen axis or the cis-normative two-sex model. Other times, the binary is less easy to identify, or disguises itself through distancing overt gendered language (think civilization vs. nature, or art vs. decoration). In all cases, its curse lingers in the language deployed and re-deployed to describe the artist and her practice. Though there are many irreconcilable binaries that cling to analyses of Florine Stettheimer, the socialite saloniste/eccentric recluse, my analysis concerns two sets of two: the public and the private, the exterior and the interior.

Rather than spend time deconstructing binaries that, frankly, deconstruct themselves, I dive into these descriptors of Stettheimer and her work. In the spirit of abundance, I offer a third, middling zone.[1] I operate on the premise that the three categories are fluid and artificial, though their fluidity and artifice do not undermine their importance. I construct my tripartite exploration of Stettheimer’s art with a sensibility that cherishes fables, that takes seriously the folkloric, but that treats academic thought with a much-needed element of play. Binaries are some of the most enduring mythologies to define western culture; so too are dialectical treatments of these binaries that incorporate a middling third. With these beliefs in mind, I consider another enduring fairy-tale: Goldilocks and the Three Bears.[2]

In this tale, Stettheimer operates Goldilocks. Rather than trying out different bowls of porridge, chairs, or beds, she experiments with creating three different types of worlds. Where Goldilocks searches for the best out of three pre-existing objects, Stettheimer attempts to create her own singular world-vision in the context of three pre-existing categories of space. Stettheimer’s worlds adapt within and transmogrify established cultural environments through the form of houses: art house, doll house, and her own house.[3] All three freely blend the public and private; all three conflate interiors and exteriors. But the artworld and its public are too broad and expansive for Stettheimer’s highly particular fantasy; meanwhile, her miniature dioramas are too intimate and self-contained to convey the full sweep of her cellophane-draped universe. In the nature of Goldilocks, I consider Stettheimer’s Beaux-Arts studio “just right.”

The phrase here, as in the fairy tale, does not necessarily mean “just right” in a universal, moral, or standardized hierarchy, or even on a somewhat agreed-upon scale. In fact, the only two individuals specified to find these objects “just right,” are Goldilocks and the young baby bear. In Pyle’s version of the tale, after Goldilocks runs home, “the little baby bear cried and cried because he had wanted the pretty little girl to play with.”[4] Here shared affection for peculiar details not only implies a physical-material link, but the potential for an emotional, social link.

Stettheimer’s “just right,” too, strikes a chord with particular individuals, who forge relationships with her throughout her life. Many scholars note Stettheimer’s tight-knit circle of treasured friends. Though eccentric and guarded, Stettheimer shared the workings of her idiosyncratic world with those she felt appreciated her confectionary, humorous, high-keyed vision, resulting in deeply intimate, enduring friendships.

In the first biography written on Stettheimer, Parker Tyler recalls an exemplary dream had by her dear friend, Pavel Tchelitchew:

A light-brown haired woman, in a dress of half-gold and half-silver brocade, appeared suddenly to him and said, ‘I am Florine Stettheimer. I love your work. I will be your friend to my last days.’—’And so,’ Tchelitchew told me gently, some years ago, ‘it was.’[5]

Stettheimer’s decorations imbue materials, objects, and things with her particular affect. She loves the objects she chooses in fabricating her fantastic environments. Objects in turn act as conduits for affect, providing the basis for tenderness and companionship.

In fact, Stettheimer, in some instances, conjured “an explicit identification of [her art]work with [her] self, as though a picture were an artist’s bodily extension.”[6] Stettheimer and her circle do not uphold a clear, categorical distinction between subject and object. Stettheimer is her body, her clothes, her decoration, her artwork.

Imagine Tchelitchew and other Stettheimer devotees expressing the underlying premises bolstering the former’s dream. Florine Stettheimer, I love your work—I love what you love and therefore I love you. I will be your friend to my last days.

♦

And what, precisely, are the boundaries between the public and the private? Why has such a distinction been made in the creation of art? All these issues are raised, although hardly resolved, by the art of Florine Stettheimer.

Linda Nochlin, 198

♦

Gallery / Art House

The first world was a GREAT BIG WORLD with a GREAT BIG PUBLIC, and it was the art institution’s world. Florine entered this world, and she decorated a smaller space within it to make a world of her own, but the art world was too big, and she wasn’t comfortable at all.

Stettheimer’s occupation with publicity and privacy factors largely in first biography written about her, Parker Tyler’s Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art. A queer poet with strong ties to surrealism, psychoanalysis, and gossip, Tyler writes with evocative and theatrical language befitting of his subject. He writes of “people and places, private and public,” as “Florine’s constant preoccupation,” and titles two back-to-back chapters: “In the Eyes of the World” and “The World in Her Eyes.”[7]

In part, I model my Stettheimer scholarship on Tyler’s.[8] He engages the many legends surrounding Stettheimer as they are, legends. Accounts of Stettheimer are already fairy-tale-esque. Stories of Florine and her two sisters living with their deserted, single mother in luxurious, opulent buildings set a folkloric scene.

Tyler considers the origins and afterlives of these legends with equal doses of seriousness and playfulness. He does not hide is role as transmitter of these mythologies, and instead reveals his own feelings and fantasies. Tyler’s voice marshals countless shifting, metamorphosing, scintillating subjectivities, which cast Stettheimer in an opalescent, flickering light that refuses static, unchanging interpretation.

In line with his psychoanalytic impulses, Tyler speculates about Stettheimer’s psychological states throughout her life. He grants a specific event much gravity in the shaping of Stettheimer’s relationship to the public: her one-artist exhibition at M. Knoedler & Company Gallery in 1916.

As the only solo show to materialize during her lifetime, the circumstances of this 1916 exhibition become central to constructing an understanding of Stettheimer’s positioning of her artwork and her persona in relation to a larger public.

Her diary suggests she felt a combination of anxiety and excitement towards entering this world. Though “delighted by the prospect of having an exhibition,” she felt “put out by the gallery owner’s lack of interest in her work,” believing “he thinks nobody will see the show.”[9] Tyler, with his signature flair for theatrics, writes “One can imagine the trepidation of this artist on ground where her art was to be tested by the barbarously intent gaze of a public with which she was not at all acquainted, and of which she nurtured reasons to be suspicious!”[10]

There are no readily available photographs of Stettheimer’s 1916 exhibition, but detailed accounts from her two primary biographers describe her creation of a multi-sensory, luminous installation bedecked with draperies and tinsel. Barbara Bloemink writes:

Stettheimer decided to decorate the gallery rooms to replicate her own rooms where the paintings usually hung…She felt compelled to present her paintings as part of an integrated environment, as she believed that an appropriate context was crucial to viewing her work. She had the walls covered with shite muslin material, and on one wall she added a cellophane fringed canopy similar to the bed she designed in her bedroom in the family’s apartment.

Tyler writes of this occasion as well, including some conjectures regarding Stettheimer’s motivations for her decorative predilections. Characterizing Stettheimer as “a thoroughgoing animist,” he states, “Florine planned a setting that would provide as little dislocative violence as possible for objects (her pictures) which might have been construed to have human feelings.”[11] In order to achieve this transition, as Bloemink indicates, Stettheimer replicated her home within the gallery. Tyler specifies:

[Stettheimer] would also effect a magical transference of Florinesque atmosphere by reproducing in the gallery the canopy over her bed, thus presenting her works in the atmosphere to which they were accustomed and in which they had been created: that of the boudoir![12]

Draping, wrapping, covering, layering, and hanging fabric throughout the space, Stettheimer coats the standardized gallery space with cherished textiles.

During the time of the 1916 show, Stettheimer would have had two primary buildings between which she divided her time. In 1914, Florine, her mother, and her sisters Ettie and Carrie all moved into their aunt’s townhouse at 102 West 76th street. While Stettheimer spent most of her days working in her studio in the Beaux Arts Building on West 40th Street, she spent time in both spaces decorating “in her distinctive style.”

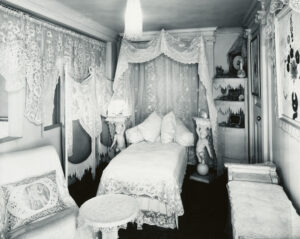

The bedroom of Florine Stettheimer’s studio at the Beaux-Arts Building, New York. Peter A. Juley & Son. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Photographs capture Stettheimer’s Beaux Arts bedroom. Stettheimer’s love for wrapping her space in textiles is immediately apparent in the amount of lace that hangs from her walls, ceiling, bedspread, and tables. At one point, Tyler characterizes this room as Stettheimer’s “interior cocoon.”

Alongside the studio photographs, those of her bedroom in Alwyn Court add significant context in understanding the Knoedler display. Bloemink states that Stettheimer’s decorative choices in the gallery “evoke the aura of Alwyn Court,” pointing out that she “added a replica of her canopied bed to the exhibition, situating it sideways against one wall.”[13] The bed is low to the ground with four corner posts twisting upwards in vertical spirals (see fig. 5). These spires hold up a sheer fabric canopy trimmed with shimmering, metallic tinsel, crowned with a monogrammed cornice. Its wooden frame is painted white with golden accents. In Knoedler’s gallery, Stettheimer reproduced this bed and hung twelve paintings around it, which echoes the bed’s proximity to her paintings hanging in Alwyn Court.

In Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, and Performativity, Eve Sedgwick characterizes “the desire of a reparative impulse” as “additive and accretive;” accordingly, “it wants to assemble and confer plenitude on an object that will then have resources to offer to an inchoate self.”[14] In Stettheimer’s environmental accumulations of lace, tinsel, cellophane, white muslin, ribbons, and canopies, I see a reparative impulse, which Sedgwick aligns with the dissolution of subject-object distinctions. In re-staging her own bedroom, Stettheimer reveals her “strongly anthropomorphic identification with her work,” which is its own dissolve of the subject-object divide.[15] With this dissolution, the interiority and exteriority lose their clear boundaries, as do public and private.

Tyler claims that in “showing the world fruits of private labor” in the Knoedler’s show, Stettheimer feared the “public,” and “staked the museum, redecorated the gallery in a ‘private’ style.”[16] Selling nothing throughout the duration of the show, and facing tepid reviews, Stettheimer experienced disappointment and alienation.

Though the public misconstrues Stettheimer’s work and by extension, her identity, the blending of public, private, interior, and exterior are apparent. This blending is an act of creating more joyful, beautiful, connective worlds, catalyzing encounters without binary divisions.

♦

The values and relations and accents of Florine Stettheimer’s art are so fastidious and incorporeal and weightless that we seem to be moving through them upon a planet smaller than ours, some large asteroid swimming joyously in its blue ether—the asteroid ‘Florine’—and getting both the experience of this delicate, remote little sphere and a sense of the grossness and preposterousness of our own earth.

Paul Rosenfeld, 1933

♦

Diorama / Doll House

The second world was a dear little world with a dear little public, and it was the miniature dolls’ world. Florine fabricated this world, and she shared her tiny dioramas through grand, operatic performances, but the gap between her shoeboxes and the audience’s stage was too large, and thar wasn’t comfortable either.

Between the Stettheimer sisters, Florine’s celebrated talent was painting. Carrie Stettheimer’s specialized skill, for which she garnered some acclaim, was building dollhouses. She dedicated her life’s work to creating the Stettheimer Dollhouse, which has remained at the Museum of the City of New York since its debut in 1945. Flora Gill Jacobs describes its public introduction as “a Doll House Warming, the first such soiree that history records,” before remarking that “it seems fitting and proper that a Stettheimer doll house should have been launched in this sociable manner.”[17] The twelve-room dollhouse boasts miniature avant-garde, modern paintings made by artists in the family’s circle of friends.

Though Jacobs muses about the appropriateness of welcoming the dollhouse with a party, neither Florine nor Carrie would be able to attend. Both had passed away the year prior, in 1944, leaving some collaborative aspects of the dollhouse unfinished. “The doll family [Carrie] Stettheimer planned to make was never begun,” and “Florine was to have painted the doll family’s portrait.”[18] So, neither Carrie, nor Florine, nor the dolls attended this dollhouse warming.

Carrie and Florine’s sister Ettie arranged the party and the bequeathing of the dollhouse to CMNY. The dollhouse warming concept is instantly charming, but also raises questions: whose “house” is this party warming? The typical contexts in which the term house-warming party appears involve celebrating people moving into a new home or premises.[19] The inhabitants of the dollhouse—the dolls—are absent.[20] The dollhouse itself is moving into a larger house—the museum. John Noble, CMNY’s curator of toys from 1961-1985, likened the Stettheimer dollhouse to a house museum, arguing to arrange the dollhouse’s decorative display as though it were in use by current inhabitants.[21] The 1945 soirée, then, becomes a housewarming for a house museum housed in a museum.

The housewarming party celebrated a dollhouse with no doll inhabitants, a house museum modeled on no actual house. Flora Gill Jacobs quotes Ettie’s statement that “none of the rooms in the doll house ‘were at all like any in our own homes.’”[22] Jacobs then makes the distinction that “where other doll houses are more literally miniature households, therefore, the Stettheimer doll house is more literally a work of art.”[23] Her primary concern throughout the chapter is demonstrating Carrie’s skill as an artist. To this end, she also draws a parallel between Carrie’s and Florine’s respective creations. Quoting Henry McBride’s descriptions of Florine’s paintings, she posits:

The ‘actual events’ the painter commemorated on canvas in ‘playful satirical fashion—true to the fantastical inner world the artist lived in’ might be related to the actual household world the doll house maker memorialized in bits of wood and cloth but true to what must have been a comparably interesting dream world of her own.

Thus, following Jacobs, if the Stettheimer dollhouse is a house museum, it is a house museum that preserves Carrie’s dream world made tangible. Though there are no literal doll inhabitants, Carrie’s projected dream world inhabitants—the would-be dolls, the potential for her dolls, or her intentional withholding of dolls—haunt the dollhouse.[24] The dollhouse warming is a celebration of the movement of Carrie’s interiority, materialized, into the public space of museums.

Jacob’s comparison relies on linking Carrie’s dollhouse with Florine’s paintings via McBride, but Florine’s multi-faceted art practice includes the recurring production of objects much closer to dollhouses: dioramas. Instead of using the “fantastic inner worlds” McBride sees in Florine’s paintings to contextualize Carrie’s dollhouse, I use the “interesting dream world” Jacobs sees in Carrie’s dollhouse to understand Florine’s dioramas.

In a foreword written for a 1947 pamphlet on the dollhouse, Ettie states “neither [her] sister Florine nor [she] had any part whatever in the production of the house.”[25] I highlight this statement to indicate that the parallels I draw do not presuppose any intentional creative cross-pollination. The similarities shared by Carrie’s dollhouses and Florine’s dioramas are coincidental but striking. For example, Carrie created her first dollhouse in 1916; Florine created her first diorama that same year.[26] Ettie characterizes Carrie’s interest in dollhouses as a “substitute for the work she was eminently fitted to adopt as a vocation, had circumstances been favorable—stage design,” musing that “she would have been an ideal link between author and receiving participant.”[27] This assertion is particularly strange, because Florine’s most widely beloved success during her lifetime was her set designs for the opera, Four Saints In Three Acts (1934). Florine designed stages. Not only did she design stages, but she used her dioramas specifically for illustrating her stage designs. On a conceptual level, the language characterizing both of the sisters’ works blends, blurs, repeats; one article examines Carrie, for example, through “a conflation of interior and exterior, imagination and reality.”[28] Carrie and Florine both began fabricating their miniature worlds (and the conflations therein) in 1916, and both artists’ miniature worlds indicate their aptitudes for stage design—their aptitudes for using intimate, tiny models to convey imaginative possibilities, played upon the larger-than-life stage before public audiences.

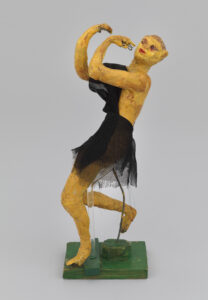

Florine’s initial diorama appeared in the month leading up to her Knoedler’s exhibition. Preparing a pitch for her unrealized ballet, Orphée of the Quat-z-arts, she unpacked miniature figures and “decided to use the empty storage case as a stage on which to pantomime the work.” She painted “the interior of the case cobalt blue and add[ed] a white and gold fringed curtain, a green floor, and an electric lighting arrangement to effectively illuminate the miniature ‘stage.’”[29] Though the whereabouts of this painted storage case are unknown, several of Stettheimer’s miniature figures and many of her preparatory assemblages remain.

In this instance, an empty storage case functions as a diorama, thus enabling Stettheimer to communicate her otherworldly ideas to an outside audience. Critics credit the designs for this ballet as “a turning point in her work,” the “first overt steps toward […] formulating her own unique style.”[30] This significance partially stems from Stettheimer’s metamorphosing, magical subject matter, synthesizing the ancient Greek mythology of Orpheus with contemporaneous French festivities associated with the annual Bal des Quat’z’Arts. The maquettes materialize “the awakening of her consciousness with regard to the aesthetic power of combining the quotidian with exquisite fantasy.”[31] Her dioramas translate her interior thoughts, interlacing imaginations and fascinations, into an externally legible format.

This impulse would find itself amplified during her design process leading up to Four Saints in Three Acts. By 1933, Stettheimer’s “conception of the décor, worked out with puppets and small maquettes, was near completion.”[32] These dioramas are perhaps the most doll-house-like of any of Stettheimer’s creations, as they are complete with miniature props, furniture, and performers. Bloemink, while recounting Stettheimer’s design process for Four Saints in Three Acts mentions: “As she had with her earlier ballet, the artist began by making three-dimensional maquettes of the costumes, performers and sets, noting in her diary that she ‘put in everything to the tiniest scrap of lace on my puppets’ (Stettheimer, 1928 diary entry).”[33] Tyler describes Stettheimer’s dolls:

Florine had made model sets and costumes for all three acts, including doll performers wearing just what she wanted, in material and cut, for the actual production; […] everything in the models carried out the paradigm of real textures she had invented: lace, feathers, glit, gloss, transparency. Living textures suggested to Florine very particular forms.[34]

Florine Stettheimer, Maquette (Faun) for artist’s ballet Orphée of the Quat-z-arts

c. 1912. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

His description foregrounds Stettheimer’s emphasis on surface texture in the dolls and their miniature stages, which would then translate to her stage designs. Notably, Tyler too describes Stettheimer’s textures as “living.”

Steven Watson also provides a wonderful description of Stettheimer’s dioramas:

She constructed three shoebox theaters, about eighteen inches high and twenty-six inches long, in minute detail. For the beach scene she used dollhouse-sized clamshells and spiraling seashells, a strand of white coral for a bench, and palm trees made with feather fronds and rose ribbon-wrapped trunks. An arch that stood behind Saint Teresa was made of tiny and large crystal beads. Behind them hung a large crinkled swatch of blue cellophane. In Maurice Grosser’s words, it was ‘a Schrafft’s candy-box version of Baroque. […] The minor saints wore cream moire silk surplices belted with white yarn, while the sailors wore aqua velvet buttons as tams. Each of the two dozen figures was rendered unique through a twist of metal foil, elbow-length white gloves, feathered anklets, bits of cherry-red taffeta, elegant ruffs, satin toe shoes, bits of shiny chintz, or tiny pearl buttons.[35]

The level of detail with which Watson writes of these doll-house-sized maquettes attests to Stettheimer’s attentiveness to decoration and adornment.

These miniature settings expanded upon the signature white-and-gold palette established in Florine’s Alwyn Court bedroom and Knoedler Gallery show, here materialized in lace, satin, sequins, beads, foil, tassels, linen, velvet, and gauze adorning tiny dolls and tiny furniture. The small-scale dioramas served as the basis for her larger-than life stage designs, direct translations for which she covered the back of the stage with “translucent veils of shimmering cellophane.”[36] Bloemink observes that for some acts, Stettheimer “designed a white gauze and beaded tassel baldachin with swirling standards resembling her Alwyn Court bed, and a gilt-and-white reviewing stand that matched her studio furniture.”[37] Though mentioned in passing, this observation—especially in tandem with the Knoedler exhibition’s recreation of the same bed—deserves further attention.

In the Knoedler show, Stettheimer attempted to transform the public realm of the museum into an environment resembling her private boudoir. For Four Saints, she starts at a much smaller, more intimate scale, miniaturizing this canopy concept to shelter her puppets. Shrinking the already intimate boudoir canopy to an even more intimate doll-sized canopy permitted Stettheimer’s entry into notoriety and celebrity; her magnified designs received accolades, praise, popularity, and fame from the theater-going American public.

Many of the diminutive components of Stettheimer’s dioramas find precedents or parallels in the furniture and ornamentation of her living spaces. In a set of Paul Juley photos vaguely labeled “Interior of Stettheimer home, New York City,” there are some images of a piece of furniture that is either (a) the same frame that acted as Stettheimer’s bed in her Alwyn Court bedroom with its canopy and cornice removed, or (b) a different object that is a direct copy of that bedframe, repurposed. Both seem equally likely, especially because Stettheimer made a copy of her bed for the Knoedler exhibition. Without its canopy and within the room setting—it stands separate from a wall of tchotchkes, beside a small side-table, and perpendicular to a fireplace and mantle—the bed appears more like a couch or settee. Instead of draping a gauzy canopy, the four, white, wooden spiral posts support shining, glittering, tinsel palm fronds. In triumphant, curling, gilded sprouts, the tinsel toppers successful metamorphose the posts into palm trees.

Palm trees, likewise, stand out in the miniature box designs for Four Saints. In photographs of these dioramas, miniscule pipe-cleaner-esque palm trees twist upwards, bursting into sprays of feathers suggesting their palm fronds. In documented images of the live performance, the palm trees appear once more. In the live-action iteration, however, the leaves look like large cellophane structures. From tinsel to feathers to cellophane, Stettheimer’s glimmering artificial plants appear in various transmutations as she adapts them for various scales of spaces and various numbers of viewers.

Stettheimer’s tendency to drape, wrap, and cover with fabric again appears in her miniatures, which feature backgrounds coated in cellophane, floors stacked with fabric, carpeting, or faux turf, and frame-like lacey borders along their outside edges. The scalloped lace trim recalls that seen in the images of her Beaux Arts bedroom, where lace frames her bed, windows, and paintings. Bloemink describes the box miniatures’ “several feet of white paper lace” as having the effect of scenes appearing “like a box of fancy chocolates trimmed with a paper doily.”[38] Her observation echoes Henry McBride’s 1947 catalog: “It was also Miss Stettheimer’s original intention to frame in the entire stage picture with an enormous lace paper frill, much as boxes of candy were decorated years ago, but she was dissuaded from this. Probably the fire laws did the dissuasion.”[39] Her doll-house-like set designs convey Stettheimer’s lace-festooned visions, but they are unable to manifest in the public sphere of the stage.

Florine Stettheimer. Costume design (Ariadne on a Panther) for artist’s ballet Orphée of the Quat-z-arts. Ca. 1912. Courtesty of the Museum of Modern Art.

In describing her design process, Stettheimer states: “When I had finished my puppet stage, the stage technician came to me with samples of materials, and I passed on everything. What appeared on the stage finally is simply an enlargement of my miniature stage, a perfect enlargement.”[40] This quotation demonstrates the intense importance she placed upon the miniature designs, and the gravity with which she treats her materials, but the ultimate lack of a lace border undermines her emphasis on perfection.

Though her designs dazzled audiences and received positive reviews, Stettheimer’s notes fixate on mistakes. She kept a handwritten list of errors “and inscribed next to each example, ‘I had to insist’—whether it was that the chorus’s seats be draped, rather than painted, or that the chorus be arranged in a pyramid.”[41] Within days of the opera’s opening, she continued to construct decorations at her own expense, such as a new velour sun, cellophane clouds, a star-spangled fixture, and two dozen cellophane flowers. Stettheimer enjoyed the success of her costuming and sets, but the miniature worlds she had built could not fully replicate themselves in accordance with Stettheimer’s dreams.

♦

More and more, she tacitly assumed that (to her guests) she presented a Veronica’s Veil image of Muse to the Art World: one who offered, for good measure, ambrosia and nectar as well as art.

Parker Tyler

♦

Studio / Our House

The third world was a middling-sized world with a middling-sized public, and it was the Beaux Arts Studio’s world. Florine lived in this world, and she invited beloved guests to share it, and it was just right.

Though Stettheimer had access to her studio since 1914, she entertained more and more frequently as years passed. After her mother Rosetta passed away, Stettheimer moved into her Beaux Arts studio apartment altogether, reportedly infuriating her sisters. Bloemink attributes the move to Stettheimer craving “independence,” because “the move allowed [her] to design the entire environment without compromising.”[42] Though her invited friends typically only experienced her downstairs spaces, she filled all of the rooms with her artworks and decorations.

The foreword to Parker Tyler’s biographical account is an aptly named reflection by Carl Van Vecthen, “Prelude in the Form of a Cellophane Squirrel Cage.” In just a few pages, Stettheimer’s lifelong friend shares the foremost images that shape his perception of her. He writes:

Whenever I remember Florine, I […] vividly recall the cellophane flowers, imagined and executed by the artist herself, looming from tall glass vases, with which, much later, she embellished her studio in the Beaux Arts apartment building. It is a pleasure to bring to mind the furniture in white and gold she had designed for her bedroom in the Francois I building, the Alwyn Court, where she slept occasionally, adjacent to her mother and her two famous sisters […] Her bedroom in her studio was more informal, but fabulous in her prodigal employment of white lace, cellophane, and crystal blossoms. I am happy to remember how she made stiff paper do her bidding when she arranged the drapes at the window in the dining room of her studio.

In the minimal space allotted to Van Vechten, he relegates about a third of his text to describing Stettheimer’s bedroom decorations. His account confirms Bloemink’s reading that Alwyn Court was a bit more restrictive, whereas the Beaux Arts studio allowed aesthetic freedom.

In all Stettheimer’s living spaces, she designed custom frames for her artwork that correlated to the canvas’s intended decorative surrounding. For example, she designed a special frame for her painting Sun (1932) that hung over a matching commode within a gilded wall motif. […] The artist integrated the commode to the painting’s frame by designing it with a complementary wooden fringe along its rim. She also placed Music (1920) between silver fringe trimmed wall sconces, in the midst of a white frame with gilding imitating fold fringe, above a “matching wood and plaster dressing table and stool of painted white drapery and gilded trim.”[43]

In her later biography on Stettheimer, Bloemink recounts:

The decoration of Stettheimer’s Beaux Arts studio astonished all visitors. The artist’s eye and idiosyncratic aesthetic was evident throughout the public and private spaces of the duplex. […] McBride described the studio as ‘one of the curiosities of the town; and very closely related, in appearance, to the work that was done in it. The lofty windows (the studio was double-decked) were hung with billowy cellophane curtains, and the chairs and tables were in white and gold […] The bedroom of Stettheimer’s studio was visible through arched windows partially draped with lace and looking out over the living room. On at least one occasion, the artist blocked the red-carpeted stairs to her alcove bedroom with a wide, white cellophane ribbon tired in a bow, forbidding access to the ‘cocoon of lace upstairs.’[44]

Again, Stettheimer wraps and covers and adorns and enshrouds. Her bedroom especially feels almost web-like in its extensive lace motifs, embroidered coverlets, and lace veil canopy.

The studio of Florine Stettheimer at the Beaux-Arts Building, New York. Peter A. Juley & Son. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Downstairs from her heavily veiled bedroom, Stettheimer would host unveiling parties for her paintings. Her first ‘unveiling’ party took place at the Stettheimer home on the upper West Side, in 1916—the year of her Knoedler’s show, the year she created her first diorama. Yet it was in her Beaux Arts studio where these unveiling gatherings became customary routines. Stettheimer also referred to these events as birthday parties, celebrating the birth of her new artworks, affirming their animate natures.

Tyler characterizes Stettheimer’s painting Studio Party (Soiree) as containing “a great deal of Florinesque atmosphere,” hypothesizing that the painting “commemorated the installment of the birthday-party habit, when a covered easel was shorn of its mystery to bring a new painting to the eyes of Florine’s little society.”[45] Tyler identifies within the frame Gaston and Isabelle Lachaise, Maurice Sterne, Avery Hopwood, Leo Stein, Albert Gleizes, and Juliette Roche. Because of Stettheimer’s emphasis on privacy, only “a handful of commentators hinted at her studio décor, the teas at which she unveiled her paintings, and her social gatherings with ‘special friends,’ but their few published accounts never included either photographs or exact descriptions of her interiors.”[46] This painting helps bridge the gaps of these undocumented gatherings, though specifically through Stettheimer’s eye and aesthetic paradigm.

Stettheimer’s harmonious decorative settings require attentiveness to every small detail. Her Beaux Arts studio included playful putti, Corinthian columns, diaphanous cloth-covered lights, shimmering nautilus shells, white beads, and billowing cellophane curtains, rendering it “the perfect setting for the artist to present her work.”[47] Though Stettheimer changed her will’s early request that her work be destroyed, or buried with her, her later hope remained that all of her work would continue to cohabitate as an ensemble. She expressed an “unwavering desire to have [her works] viewed as a single unit within the appropriate context of complementary frames, furniture, and decorative art.”[48] Following Tyler’s speculation, I argue she wanted to prevent dislocative violence for her pictures. Her living pictures and her living decorations existed within the network of her own living self and the living invitees who moved throughout the space.

Though there seem to be no extant images of her canvasses veiled, one can intuit the theatricality involved in performing the unveiling before an audience. Tyler muses: “at least once—she must have stepped to a covered easel, unveiled it, and brought to the light for a long, unscheduled moment that richly unique climate of identified individuals which, parallel to the fabled races of fauns and mermaids, were part-human and part-Florinesque.”[49] The fantastic worlds within her canvas acts as part of a larger fantastic world within the studio space, becoming another fabric-swaddled, cocooned, cherished, living object in the network of its surrounding environment.

Stettheimer’s Beaux Arts studio, over the course of her life, became a sacred, affirming, exquisite world for her and her social circle. Though private, Stettheimer allowed trusted individuals to enter her fantastic space. Tyler includes an account of his own attendance at one of her parties, stating he “had come to enjoy himself in delightful company—a little removed from rough reality, but so what?” and describing that Stettheimer’s home “tended to produce an ambiance of fantasy.”[50] The parties provided a space of comfort for the attendees, as is apparent in an anecdote of one Stettheimer party in which Adolph Bolm had to stay overnight and “was obliged to sleep in one of old Mrs. Stettheimer’s frilled cambric nightgowns,” in which he “improvised a dance on the lawn.”[51]

The meticulous cultivation of her private extravagance is what grants Florine Stettheimer’s studio its otherworldliness, and the affirmation that comes with it. Cecile Whiting argues that the private nature of Stettheimer’s interiors undoubtedly enabled her studio to serve increasingly in the late 1930s as a safe haven for social gatherings of gay men involved in the arts, including Pavel Tchelitchew, Charles Henri Ford, Monroe Wheeler, and Glenway Wescott; a number of lesbians such as Romaine Brooks and Natalie Barney were also guests in her studio […] [These rooms] functioned eventually as a sanctuary in which women and men could express personal identities that, increasingly banned in public, forced them to retreat into the privacy of homes.[52]

Stettheimer’s rooms are more than just “a type of self-portrait in three dimensions,” although that in and of itself is already affirming for her own personhood.[53] The Beaux Arts studio space was “just right;” it served as a world for Stettheimer’s intimate, queer community, acting as a site for emotional, intellectual, and aesthetic encounters. Her studio cultivated the comfort not only of her living paintings, but of her beloved friends, who shared in cherishing the idiosyncrasies of her aesthetic visions.

[1] Why are binaries so popular anyway, when we all know the rule of three is so satisfying?

[2] Though there are many, many versions of this fairytale, I will be referencing the most popular folkloric iteration in which a little girl named Goldilocks enters the home of a family of bears (Papa Bear, Mama Bear, and Baby Bear). Loosely, I have in mind Katherine Pyle’s 1918 written account, “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” from her book Mother’s Nursery Tales. In addition, I’m picturing two animated versions: Disney’s 1922 Laugh-O-Gram “Goldie Locks and the Three Bears,” plus the 1935 Ub Iwerks ComiColor cartoon known as “The Three Bears.” All three of these versions existed during Stettheimer’s lifetime, and Stettheimer herself wrote of her affection for “Walt Disney cartoons.”

[3] Maybe a more apt guiding-metaphor would be some crossover between Goldilocks and The Three Little Pigs, given that the three little pigs create three types of houses. Stettheimer too constructs three categories of houses, but none of hers are so easily demolished as the first two pigs’ straw and stick huts. I find Goldilocks more apt because of its emphasis on a singular, curious heroine in relation to her experiences of too much, too little, and just right. I

[4]Katherine Pyle, “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” in Mother’s Nursery Tales (New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1917), 213.

[5] Parker Tyler, Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1963), 100.

[6] Ibid., 24-25

[7] Parker Tyler, Florine Stettheimer, 24.

[8]My embrace of Parker Tyler is at odds with some contemporary authors’ arguments. For example, Barbara Bloemink states Parker Tyler’s biography is “the most prominent source of inaccurate information about Stettheimer and her work,” pointing out that there is only one recorded meeting between the two and paraphrasing Tyler’s poetic text to conclude “he openly [admits] that he made up and exaggerated a great deal of what he wrote.” Bloemink contends that writers who quote Tyler “diminish Stettheimer’s importance.” I agree that Tyler’s writing is subjective, imaginative, and at times, exaggerated in its poetic diction. Where Bloemink sees a problem in Tyler’s willful rejection of objectivity and detachment, I see special value. Rather than diminishing Stettheimer’s importance, I find Tyler’s words a tribute to that very importance, with their theatricality and whimsy following the spirit of her own subjectivity. See Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo, eds., Florine Stettheimer: New Directions in Multimodal Modernism, (Toronto: Book Thug Press, 2019), 20-21.

[9] Barbara Bloemink, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer (New Haven: Yale University Press 1995), 71.

[10] Tyler, Florine Stettheimer, 27.

[11]Ibid., 26.

[12] Ibid., 26-27.

[13] Barbara J. Bloemink, “Crystal flowers, pink candy hearts and tinsel creation: the subversive femininity of Florine Stettheimer,” in Women Artists and the Decorative Arts, 1880—1935: The Gender of Ornament, 197-213 (Burlington: Ashgate, 2003), 203.

[14]Eve Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 149.

[15] Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers,” 202.

[16] Tyler, Florine Stettheimer, 30.

[17] Flora Gill Jacobs, A History of Doll Houses (New York, 1953), 289.

[18] Ibid., 297.

[19] “house-warming, n.”. OED Online. September 2020. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/view/Entry/88946 (accessed September 29, 2020).

[20] Scholars contest whether Carrie intended to complete dolls for the house. Flora Gill Jacobs suggests Carrie conceived of dolls as part of her design. Former MCNY toy curator John Noble’s research found that Carrie had planned to create dolls for the house. Jean Nathan, however, writes in the New York Times Magazine, that “dolls had never been part of Carrie’s original conception.”

[21] John Noble, A Fabulous Dollhouse of the Twenties: The Famous Stettheimer Dollhouse at the Museum of the City of New York (New York: Dover Publications, 1976), 6.

[22] Jacobs, A History of Doll Houses, 293.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “In a letter to Lachaise in 1931, she thanked him for a drawing and an alabaster sculpture he had made for the house and wrote: ‘I am now hoping [ the dolls ] will never be born, so that I can keep them forever in custody, and enjoy them myself, while awaiting their arrival.’” See Jean Nathan, “Doll House Party.”

[25] Ettie Stettheimer, “Introductory Foreword,” in The Stettheimer Dollhouse (San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2009), 11.

[26] Ettie describes Carrie’s first dollhouse, which she constructed for a charity raffle to combat an epidemic of infantile paralysis. See Ibid., 10.

[27] Ibid., 11.

[28] Janine Mileaf, “The House that Carrie Built: The Stettheimer Doll’s House of the 1920s,” Art & Design Vol. 11, 1996: 78.

[29] Bloemink, 72

[30] Ibid., 48.

[31] Stephen Brown and Georgiana Uhlyarik, Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 27.

[32] Florine Stettheimer: Still Lives, Portraits, and Pageants, 1980.

[33] Barbara J. Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers, Pink Candy Hearts and Tinsel Creation: The Subversive Femininity of Florine Stettheimer,” in Women Artists and the Decorative Arts 1880-1935: The Gender of Ornament, ed. Bridget Elliott (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002), 207.

[34] Ibid., 51.

[35] Watson, Prepare for Saints, 225.

[36] Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers,” 207.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid., 207.

[39] Henry McBride, Florine Stettheimer (New York: MoMA, 1946), 26.

[40] Bloemink, The Life Ant Art of Florine Stettheimer, 191-192.

[41] Ibid., 195.

[42] Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers,” 206.

[43] Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers,” 205.

[44] 178

[45] Tyler, Florine Stettheimer, 108.

[46] Cecile Whiting, “Decorating with Stettheimer and the Boys,” American Art Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2000): 37.

[47] Bloemink, “Crystal Flowers,” 206.

[48] Ibid., 210.

[49] Tyler, 181

[50] Ibid., 94.

[51] Ibid., 95.

[52] Whiting, “Decorating with Stettheimer,” 46.

[53] Ibid., 35.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.