An “Imaginary Chisel”: Collaborative Collage in Victoria Chang’s Dear Memory

Is that emptiness in the shape of a human being a mark of violent erasure, or of the hospitality of the artist whose work is open to other past or future histories? —Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory[1]

In the final pages of her book The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust, Marianne Hirsch turns to a curious image from Patricia Williams’s book The Rooster’s Egg: On the Persistence of Prejudice. Hirsch describes Williams’s experience visiting a friend whose husband was both a painter and Auschwitz survivor. His paintings, which all preserved patches of bare canvas in the shape of a small human, demonstrated to Williams a “complete representation of…the erasure of humanity that the Holocaust exacted.”[2] Williams then reports revisiting his gallery in her dream, where from the holes of each painting appears her great-great grandmother, a figure whom Williams could never possibly meet, whose only lasting record on file was the documentation of her enslavement through a National Archives property listing. Here, the emptiness in the picture supports new and unknown possibilities for repair and reunion. Williams recognizes her great-great-grandmother inside the paintings’ human-shaped gaps, going so far as to conclude “I would know her everywhere.”[3]

Williams’s anecdote is an insightful example of postmemory, which Hirsch coins in The Generation of Postmemory as “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before.”[4] In this relationship, the past can be addressed through forms of “imaginative investment, projection, and creation” that generate paths toward reparative intergenerational narratives.[5] Through postmemory, we can reframe the gaps in our archives, transforming marks of erasure into spaces for dialogue between the past and future. Postmemory supports these alternative modes of discovery, such as dreams and shared galleries, that open possibilities to reach each other beyond the archive.

Hirsch’s postmemory is central to Victoria Chang’s 2021 hybrid collection Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief. Chang cites Hirsch’s theory in the acknowledgments of Dear Memory as representative of her own lived experiences and engagements with family history. In a later conversation with poet Brandon Shimoda, Chang emphasizes how postmemory transforms diasporic narratives of exclusion, longing, and loss into reparative opportunities for continued imagination and conversation.[6] Considering the importance of postmemory to Chang’s self-described personal and artistic practices, it is no coincidence that Dear Memory challenges conventional understandings of historical documentation and narration, demonstrating instead the qualities of a postmemorial archive.

A record of Chang’s personal encounters with her family archives, Dear Memory consists of a series of letters addressed to a variety of subjects, including ancestors never met, relatives no longer present, and Chang’s former peers and writing mentors. The book also incorporates visual collages made with materials from Chang’s family archives, including photographs and legal certificates. Like the paintings from Williams’s anecdote, Chang’s collages portray empty marks in the shape of human bodies. Chang uses materials such as newspaper print and handwritten testimony to cut into and cover over her family’s photographed faces and figures, “erasing” their presence from the surface:

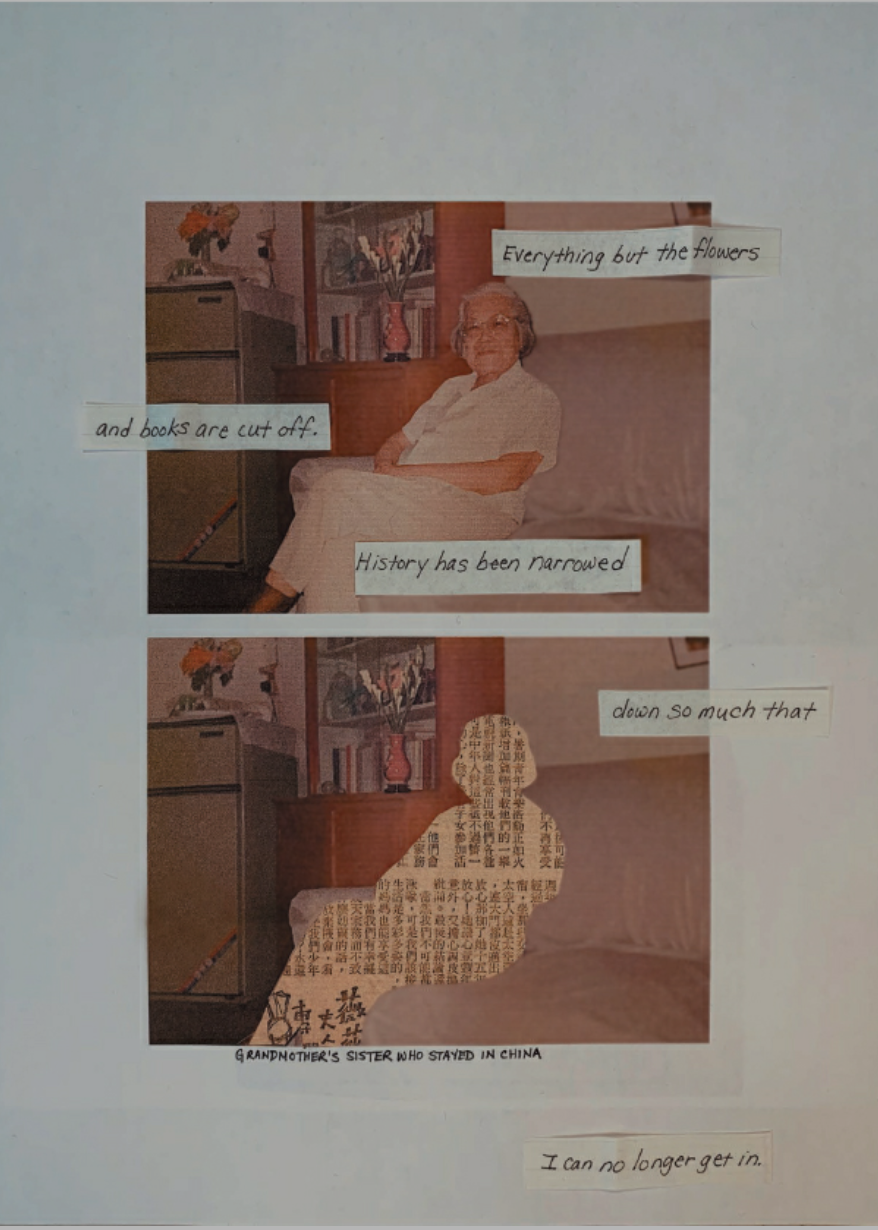

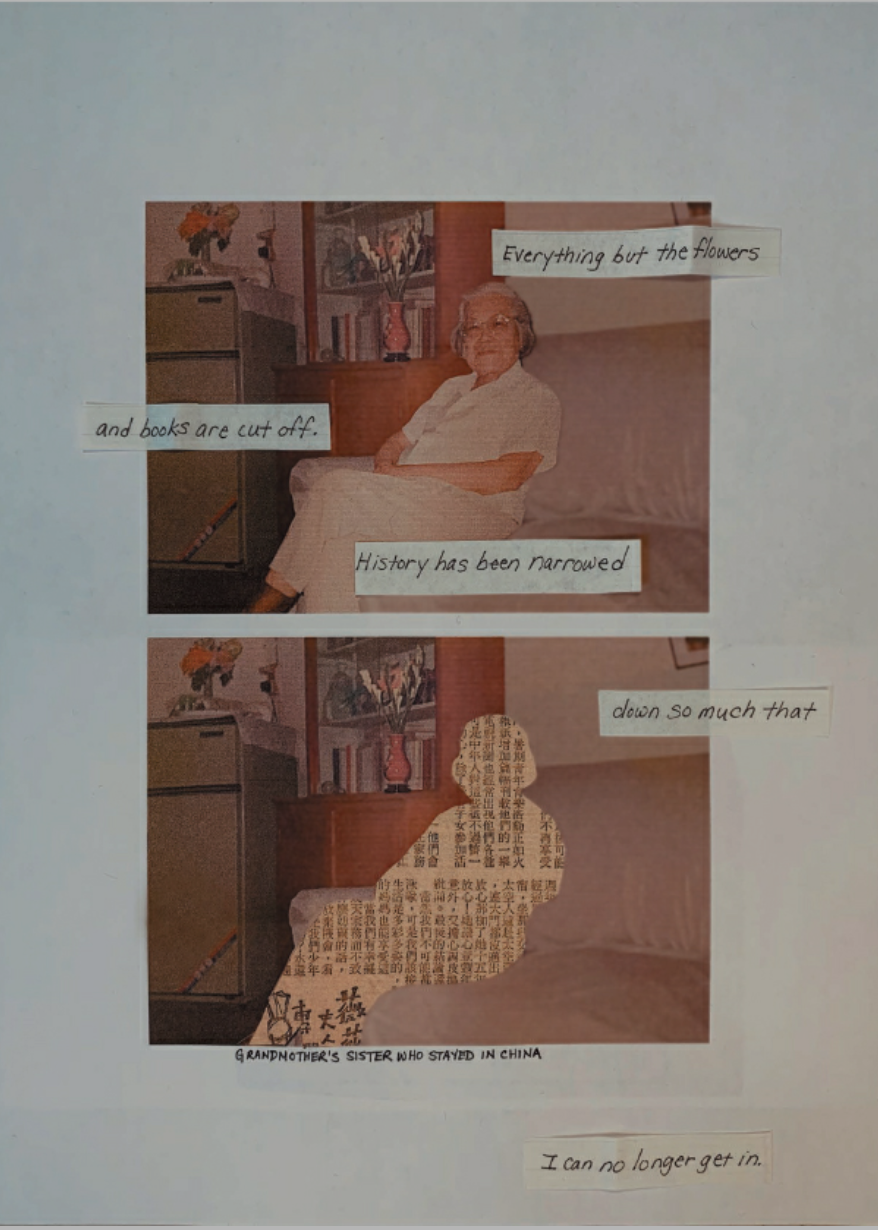

Victoria Chang, Dear Memory, p. 10: “Grandmother’s sister who stayed in China.” Credit for all images: Victoria Chang, selections from Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief. Copyright © 2021 by Victoria Chang. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Milkweed Editions, milkweed.org.

This may appear as a violent removal or disavowal of the photographed family subjects. And, in a way, we can certainly feel the pains of separation folded into these images. Chang belatedly discovered her family records in 2019, four years after her mother’s death and ten years after her father’s stroke and cognitive decline. This personal context provides substantial insight into Chang’s creative process. She describes the moment of her archival discovery using terms of unfulfilled desire: “I had opened the box to find answers, but all I found were more questions.”[7] Left unanswered by these archives, Chang explores and refines her questions in her collages. A closer look into Chang’s visual work in Dear Memory reveals her collage cuts as performances of intergenerational connection. In a postmemorial move, she transforms archival silence and absence into opportunities for commemorating her family, past and future. And most notably, Chang’s creative collage process also reveals to us how collaboration—both artistic and familial—is at the heart of her work, reshaping marks of erasure into something new, something changing.

—

Chang wrote Dear Memory before knowing of Hirsch’s postmemory, but when she later learned of the concept it “seem[ed] to encapsulate both [the] book and [her] own experiences.”[8] In Dear Memory, Chang reflects on her upbringing as a second-generation Chinese-Taiwanese American as inseparable from her family’s background—their migration from China to Taiwan during the Chinese Civil War, then from Taiwan to Michigan, where Chang was born and raised. In the acknowledgements of Dear Memory, Chang relates her strained understanding of this family history with a quote from postmemorial artist Yvonne Singer: “I was between worlds, alienated from the Canadian world of my peers and excluded from the history and culture of my parents, who placed a veil of secrecy on the past.”[9] Chang’s letters and collages attempt to reach across the veil of secrecy, “try[ing] to know” her family “through imagination and within silence,”[10] and this postmemorial quality of Chang’s work is also visible in her description of Dear Memory’s creative collage process:

I used to think I was a transcriber of my own experiences and memories, adding an image here and there, but now I think I am more of a shaper. I take small fragments of imagery, memory, silence, and thought, and shape them with imaginary hands into something different. What’s left doesn’t need to have a firm, precise shape that resembles reality though. It can be unshapely. Splayed.[11]

Chang’s account of becoming not a “transcriber” of history but a “shaper” of the imaginary defines her lived experiences with family silence and archives, and it is an important distinction for understanding the context of her work. By positioning herself as a shaper of the imaginary, Chang embraces unconventional modes of engaging the past, such as erasure as a possible method of repair. While we typically associate erasure from the record as a failing of history, for Chang, erasure can serve as an entry for love and commemoration. This can often be the case for postmemory—we preserve records from the past, but when there is no clear or surviving record of those who came before, we attend to their absence just as ardently.

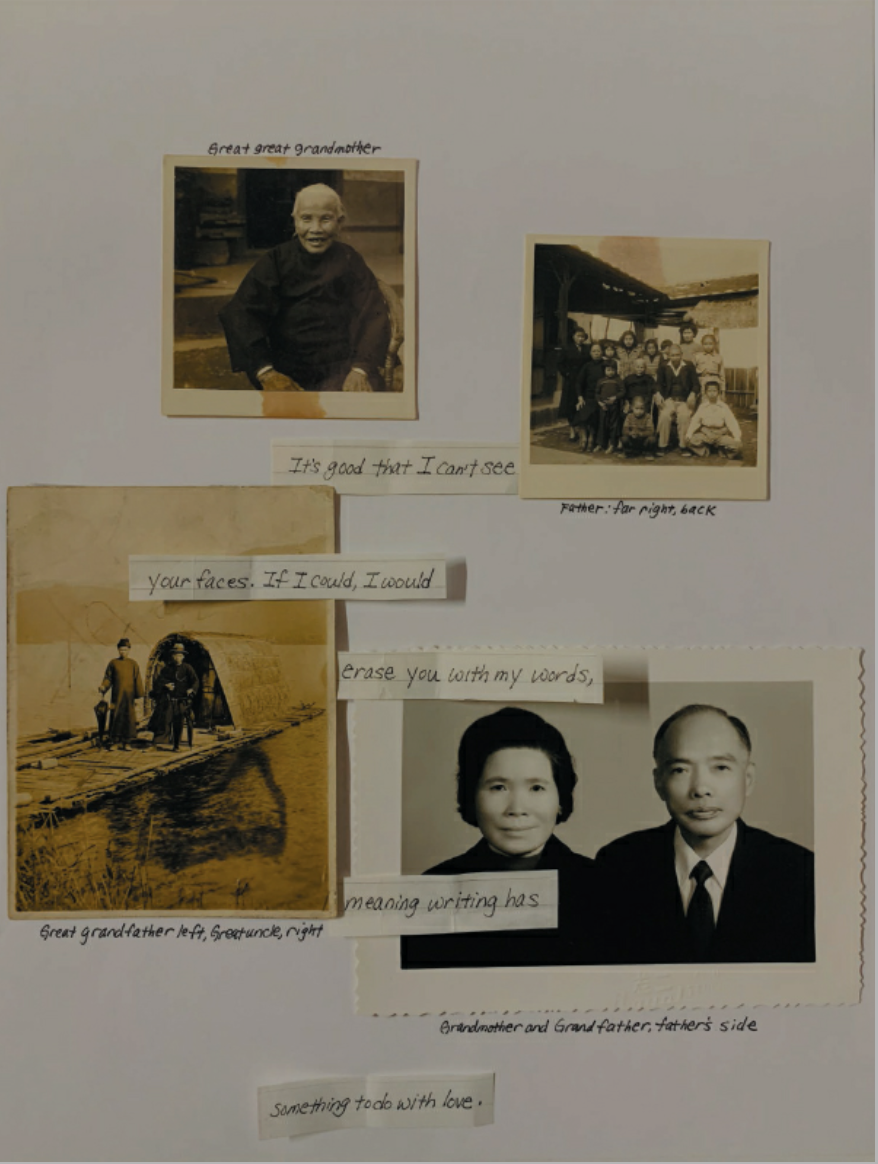

Chang directly addresses erasure, repair, and love in a collage of her paternal relatives, “Father’s family.” In it, she assembles and labels four family photographs on top of a sheet of paper. Aligned to the center of the page, creased paper strips of handwritten poetic lines narrate the scene:

Text: “It’s good that I can’t see / your faces. If I could, I would / erase you with my words, / meaning writing has / something to do with love.”[12]

Chang’s poetic narration raises several questions that the displayed photographs alone would not convey. Her speaker begins with a declaration that she cannot see the photographic subjects, but in her collaged arrangement they are clearly visible. Additionally, Chang suggests that the practice of writing, which erases her relatives from view, can be an act of love. How might we understand this formulation of erasure as reparative and loving? It is perhaps better seen in two other photographic poem collages of Chang’s maternal relatives, “Grandmother who left China” and “Grandmother’s sister who stayed in China.” In these collages, Chang actively alters the contents of the family photographs, obscuring her family members from easy view:

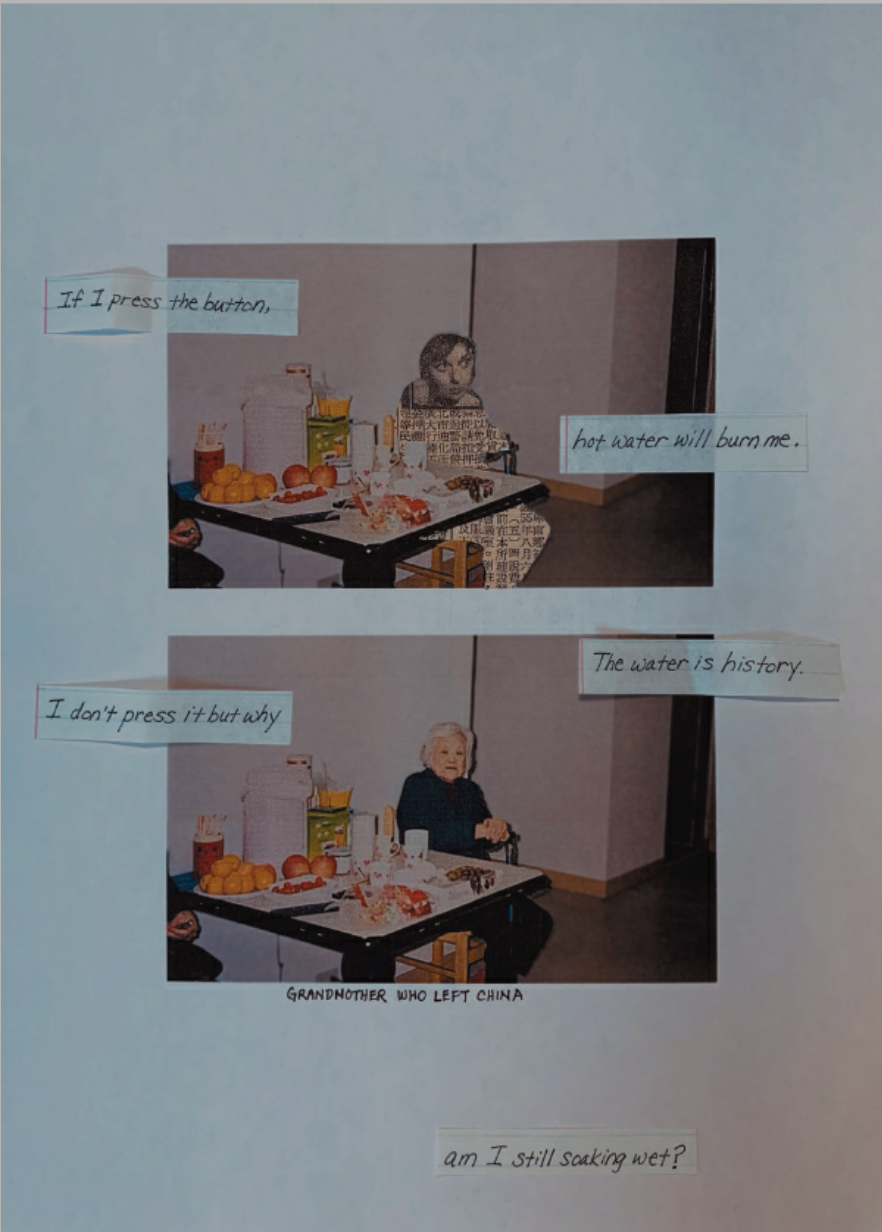

Contrasting with her photograph assemblage in “Father’s family,” Chang structures these poem collages as a two-part sequence with an original and altered photograph. Chang removes the photographic subject in the altered image, layering Chinese newsprint underneath the cutout human figure. This creates a visual effect of family figures effaced by language or, as the paternal relatives’ collage might suggest, erased by words.

Interestingly, Chang’s poetic narration in her maternal relatives’ collages explores photographic composition, especially elements of framing and detail, as a means to create an understanding of history:

Text: “If I press the button, / hot water will burn me. / The water is history. / I don’t press it but why / am I still soaking wet?” (pg. 9: “Grandmother who left China”)

Text: “Everything but the flowers / and books are cut off. / History has been narrowed / down so much that / I can no longer get in.” (p. 10: “Grandmother’s sister who stayed in China)

In “Grandmother who left China,” history is described as hot water, referring to the dispenser visible in the photograph’s foreground. Despite not pressing the dispenser’s button, Chang’s speaker reports being doused by water, becoming an unwilling recipient or witness of history—recalling Chang’s previous remarks of understanding her upbringing as inseparable from her family’s background. Although Chang’s speaker may not consider herself to be connected to or represented by the photographed scene in the collage, its history, its water, still reaches her. Meanwhile, in “Grandmother’s sister’s who stayed in China,” history is far out of reach despite the speaker’s best efforts. Chang’s speaker narrates the photograph’s framing, which cuts off “everything but the flowers / and books,” including the subject, Chang’s grandaunt. And with history narrowed down, Chang’s speaker is also cut off from the photograph, cut away from the past.

As such, Chang’s collage cuts visually express a severed yet ongoing connection between photographic subject and viewer-collager, a dynamic true to her own lived experience. These cuts outline familial bodies as sources of absence, silence, and most importantly, continued conversation. After all, while Chang’s speaker is cut away from the past, she too cuts into the family album with the present, recording the questions discovered around the photographs.

—

One possible concern regarding Chang’s collage cuts can be that they overextract from family archives, creating an even narrower and estranging field of vision into history and memory. While postmemory may view these revisions as creative opportunities, other perspectives might view approaching family archives with such abrupt and violent cuts as inhibiting connective efforts, especially when bodies are cut from the frame. New York Times critic Maya Phillips expresses this reservation, stating that the structure and language of Chang’s letters and collages insert “cool intellectual distance” between herself and her family history, marking an overall failure to intimately correspond with the past. However, Chang’s interviews and personal essays suggest the opposite, revealing that the creative collage process itself forms a tangible connection to her family and past.

This is not to say that Chang rejects the presence of violence in her work—in a Between the Covers podcast interview with David Naimon, Chang affirms that her collage cuts, while admittedly violent, activated new points of archival entry, allowing her to “change” the historical record:

DN: In your conversation with E.J. [Koh], you said that when you replace the actual face in a photograph with a cut out representation where you’ve replaced their faces with a representation of silence or the unknown, that you’ve both found it comforting and activating for you. I wanted to hear about that, how you’re confronted with these documents with a presence and that you insert an image of your own, which is an erasure in order to engage with them better or more or in a way that works best for you.

VC: It’s a form of violence I’ve done to these poor people in these photos….what you’re doing is you’re cutting people up and putting them on display. Maybe I should have done it with my own face, not their faces…. The act of cutting these faces out felt like [an acknowledgment] that perhaps an understanding of the self is in some ways a form of violence on other people, other stories, and other histories…. In some ways, cutting and changing these photos was a way of maybe acknowledging that I’m changing things, I’m changing history. I’m probably getting it all wrong but it’s okay because I’m making this thing a new thing out of it.[13]

Here, Chang’s response illustrates the creative collage process as a way to visually preserve sources of silence and absence. But her collages also initiate transformative visual dialogue, stirring the histories enclosed by rigid photographs into motion. By rejecting static or conclusive histories, Chang rejects the notion of permanent exclusion from the past.

One example of this is in an interview transcript collage of her mother, where Chang revises the visual record by combining oral and photographic histories. While going through her family archives in 2019, Chang separately recovered a digital recording of an oral history project she had conducted with her mother in 2007. Chang explains the significance of this project, which she had disguised as a falsified school assignment, as the singular instance of her mother addressing the past:

This was the only time my mother had ever spoken to me substantively about her past. There weren’t a lot of extra words. I could see how memory works (and fails) in fragments as my mother answered my questions—describing images of pickled vegetables, a servant escaping, a mother holding the hand of the wrong child.[14]

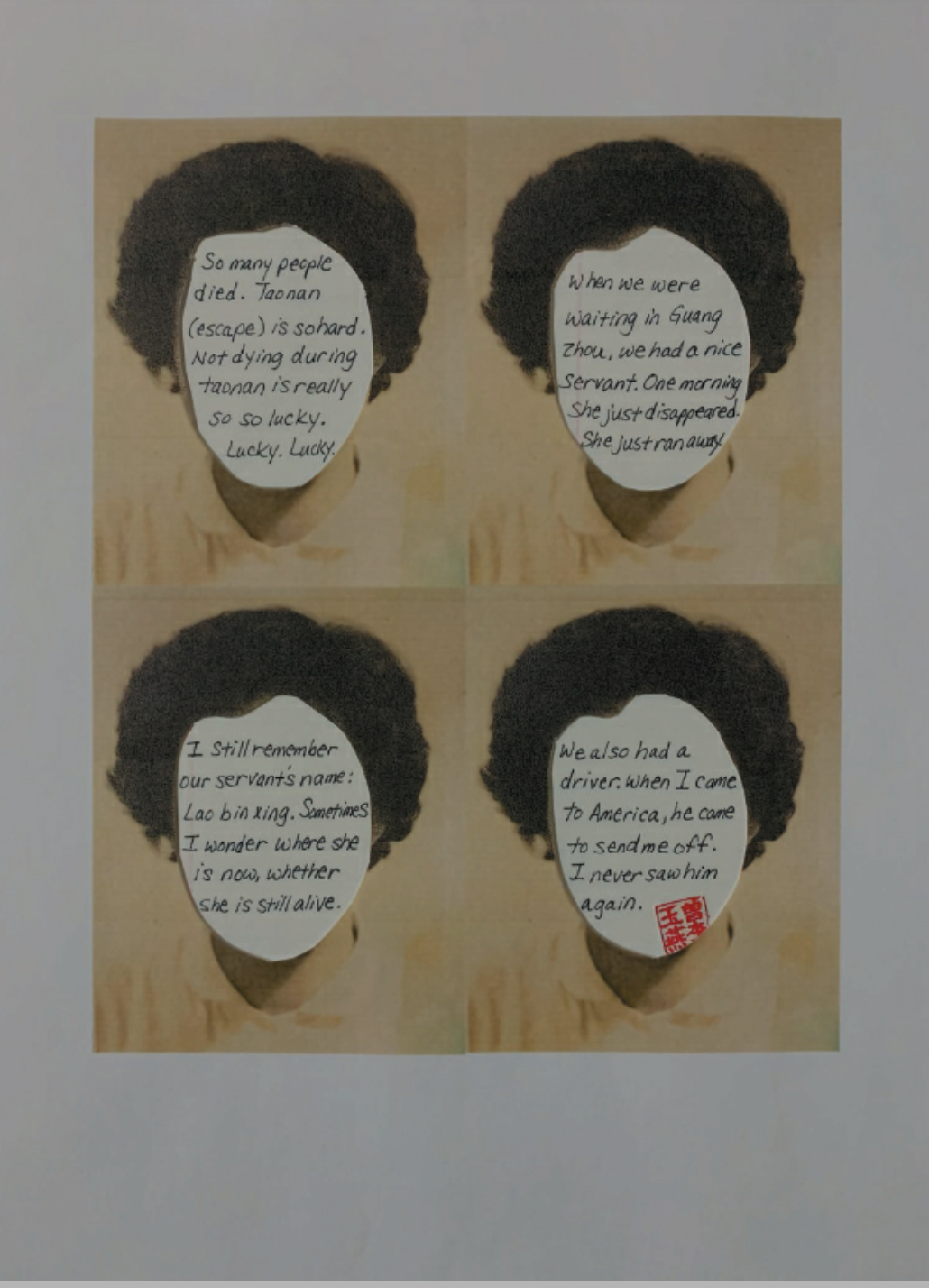

In her transcript collage, Chang cuts her mother’s face from four photocopies of a portrait. Below the photograph, she layers transcribed segments of her mother’s interview responses, shaped into the face(s) of her mother:

Top left: So many people died. Taonan (escape) is so hard. Not dying during taonan is really so so lucky. Lucky. Lucky.

Top right: When we were waiting in Guang Zhou, we had a nice servant. One morning she just disappeared. She just ran away.

Bottom left: I still remember our servant’s name: Lao bin xing. Sometimes I wonder where she is now, whether she is still alive.

Bottom right: We also had a driver. When I came to America, he came to send me off. I never saw him again.

Visually, Chang’s collage manipulations illustrate oral history cutting into photographic history. Her mother’s face is again effaced by language, erased by words—in this case, from her own narrative voice on record in the form of Chang’s handwriting. This creates a contradictory effect for Chang’s mother, who is simultaneously cut out of the picture while simultaneously granted personal narrative agency. Although we cannot see her face, as external viewers we can hear her voice and testimony, which would be absent from the unaltered photograph.

Like the previous collages, Chang’s textual insertions assess the intergenerational connections across history and memory. Here, Chang’s particular interview selections emphasize memory fragments, where details of her mother’s migration such as the whereabouts of a previous servant and driver take up a substantial amount of text space, thus becoming a major part of the portrait. This raises further attention toward the collage’s multiple layers of absence—an absence in the image (mother’s face) effaced by absence in the text (the servant, the driver). But what first appears to be Chang’s total removal of her mother instead cuts through and transforms the pervasive silences upheld by the static portrait, as well as her mother’s ordinary day-to-day refusal to narrate the past. The resulting collage, made with Chang’s imaginary hands, lovingly crafts the shape of her mother’s voice as inseparable from her own.

—

Chang’s craft essay “Dear Memory: On Creative Struggle, Stretching, and Asking for Help” reveals the collage process to be intimately connected to her associations with family. More specifically, her relationship to paper arts is deeply connected to her mother:

My mother loved paper arts, and I remember stacks and stacks of origami paper and various patterned paper everywhere in our childhood home in West Bloomfield, Michigan. She was always folding origami or cutting paper to make things. She had encouraged my visual art, and I remember much of my childhood through high school taking various studio art classes she had signed me up for.[15]

Created with a combination of craft materials previously used by her mother and daughters, Chang’s collages in Dear Memory are not just artifacts but portals of an intergenerational exchange through art. Her collaged endeavors move to erase, shape, and change history and its forms of silence and absence. Rather than perpetuating or maintaining previous forms of disconnection, as suggested by Phillips, Chang’s collages primarily commemorate her mother’s love for paper arts, and of their shared life together.

In this light, Chang’s poetic archive in Dear Memory emphasizes reparative erasure as a form of commemorative connection. But it is imperative to recognize that Chang’s personal connection to paper arts did not immediately create an affirming creative process. Although Chang felt a strong urge to include images in Dear Memory in order to “explore the visual and slippery nature of memory and history,” the image work quickly became a source of major anxiety and disruption for her.[16] What enabled Chang to overcome this challenge was to deviate from her typical artistic practices. Instead of working alone, she reached out to a broad network throughout the drafting stages of Dear Memory. Chang’s correspondence with poet and visual artist Monica Ong, who introduced her to various image-text and paper collage techniques, proved to be especially influential to the visual components of Dear Memory.[17] So, in addition to commemorative connection toward family, we can see how Chang’s collages represent the strengths of communal support and collaborative artistry.

Both commemorative and collaborative, Chang’s self-described collage process ultimately affirms the significance of the visual work in Dear Memory. This imaginative reshaping impacts not only Chang’s understanding of her family history, but her own approach toward writing and self-authorization. We can see this in her acknowledgments, where she describes the sadness, shame, and joy that accompanied the creative process of Dear Memory. Referencing Jeanette Winterson’s conceptualization of the writer’s self-made chisel, Chang articulates her own version that she honed through Dear Memory, her unfinished and imaginary poetic chisel:

I’m still learning how to make my own chisel, but everything I write, no matter how crude, is an experiment with my unfinished chisel. Each time I sit down, I pull out my imaginary chisel, listen to the words that come up, like eavesdropping, crane my neck into language, into memory, into silence. And each time I write, the chisel becomes more and more finished and distinctly mine. And with each word, I become more and more myself.[18]

Although Chang describes the chisel as part of her writing process, the chisel can possess dual possibilities as both writing instrument and cutting tool. With her imaginary chisels, Chang reshapes the family archive as not rigid and unchanged but as an ongoing record, unfinished and unshaped. This necessarily reshapes Chang herself, who discovers inside their shared silence a living archive of shadows, a gallery toward future dreams.

[1] Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 248.

[2] Quoted in Hirsch, 248.

[3] Hirsch, 248.

[4] Hirsch, 5.

[5] Hirsch, 5.

[6] Emma Cleary, “What postmemory makes possible: A Conversation with poets Brandon Shimoda and Victoria Chang,” University of British Columbia School of Creative Writing, March 13, 2023, https://creativewriting.ubc.ca/news/what-postmemory-makes-possible/.

[7] Victoria Chang, “Dear Memory: On Creative Struggle, Stretching, and Asking for Help.” Poets and Writers Magazine 49, no. 6 (2021), 25.

[8] Victoria Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief (Minneapollis: Milkweed Editions, 2021), 145.

[9] Quoted in Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 145. Italics in original.

[10] Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 145.

[11] Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 143.

[12] Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 34.

[13] David Naimon, host, Between the Covers, podcast, “Victoria Chang: Dear Memory,” Tin House, 2022, https://tinhouse.com/podcast/victoria-chang-dear-memory/ Transcript available: https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-victoria-chang-interview/

[14] Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 144.

[15] Chang, “Dear Memory: On Creative Struggle, Stretching, and Asking for Help,” 27.

[16] Chang, “Dear Memory: On Creative Struggle, Stretching, and Asking for Help,” 33.

[17] Chang, “Dear Memory: On Creative Struggle, Stretching, and Asking for Help,” 31.

[18] Chang, Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, 146.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.