Whitework Textiles, White Supremacy, and “Whitework” as a Call to Action

This theory of human culture and its aims has worked itself through warp and woof of our daily thought with a thoroughness that few realize. Everything great, good, efficient, fair and honorable is “white.” Everything mean, bad, blundering, cheating and dishonorable is “yellow,” brown and black.[1]

— W. E. Burghardt Du Bois

Whiteness: that powerful place that makes invisible, or reappropriates things, people and places it does not want to see or hear, and then through misnaming, renaming or not naming at all, invents the truth—what we are told is ‘normal’, neutral, universal, simply becomes the way it is.[2]

— Heidi Safia Mirza

The term white supremacy is usually associated with localized regimes, particularly with the American Old South and apartheid South Africa. But as I pointed out earlier, in a broader sense the history of the world has long been a history of white supremacy, in that Europeans basically controlled the globe and were the privileged race.[3]

— Charles W. Mills

The word “Whitework” references forms of white-on-white embroidery and quilting popular in the 16th to 19th centuries throughout Europe, Scandinavia and North America. Considered the epitome of a young woman’s needleworking skills, whitework required patience, time, focus, precision, and a steady hand. Unsurprisingly, these pristinely stitched textiles were often employed to metaphorically uphold attributes of whiteness that reflected favorably upon the needlewomen themselves, and the societies to which they belonged. In many so-called Western societies today, white continues to evoke innocence, purity, and virtue, all attributes that have been weaponized throughout history to exert control over specific populations such as women, ethnicized colonial subjects, slaves, and their descendants.[4]

— Sonja Dahl

Artist, researcher, writer, and educator Sonja Dahl suggests connections between whitework textiles, whiteness, and white supremacy.[5] In her essay cited above, Dahl reimagines the term “whitework” as a cultural process and a call to action for white people, like herself, to acknowledge their “implicit benefit from systemic racism” and do the necessary work of unraveling structural whiteness and white supremacy.[6] She notes that whitework textiles were not historically used to talk about these kinds of radical politics.[7] In her art works, Dahl draws on the material culture of whitework textiles to render whiteness visible as a foundational, inescapable, yet often deliberately denied and invisibilized structuring force. She mobilizes historical whitework embroidery and quilting to call attention to white supremacist ideologies like manifest destiny, and to histories of American Westward expansion and settler colonialism. Through these works, the artist takes responsibility for her own whiteness and white settler identity, and calls on other white individuals to do the same. Whitework textile techniques may thus be reclaimed as a form of responsibility, reckoning, and repair.

Whitework textiles were especially popular in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Europe and the United States, a time when new ideologies of whiteness and white supremacy were theorized and popularized. The color white was invoked to uphold white supremacist ideals of purity and beauty, often in opposition to Blackness. These temporal and ideological connections between whitework textiles and white supremacy, I suggest, are no coincidence. Dahl’s artworks provide touchpoints through which to consider relationships between whitework textiles and ideologies of whiteness and white supremacy, supported by scholarship in decolonial and Black studies, where scholars have made clear that whiteness and white supremacy are not only imposed through legal and social regimes but also echo through material culture.

As a counterpoint to discussions of Dahl’s art works, the writing surveys instances when whitework and quilting were used to actively uphold and promote white supremacy. Citing examples of Oregon Trail quilts and quilts made in support of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan, I examine how quilting was weaponized by white Christian American women to actively advance white supremacist organizations and objectives. (Content warning: The section on “Quilting white supremacy” contains images of quilts made in support of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan.)

In keeping with the theme of this issue of Dilettante Army, the text considers Dahl’s artworks as a type of correction in their attempts to expose and unravel whiteness and white supremacy. This writing investigates the possibilities of whitework—a slow, difficult, and at time contested practice—in confronting these structures. And it raises critical questions about the possibilities and limitations of whitework as an antidote to such deeply entrenched, pervasive, and oppressive systems.

Whitework and white work

Sonja Dahl, Whitework: Surrender This Story of Salt, cotton cloth, thread and quilt batting, salt, whitewashed poplar and hemlock, 60” x 60” x 66”, 2017.

Dahl recounts reading a friend’s post on Facebook many years ago, in which he asked his white friends to share what their white identities meant to them. Her mind raced to fill “a blank white expanse, seemingly contentless and void.”[8] This response, Dahl recalls, “has haunted me to this day and pushed me to delve deeper, to question what whiteness is, how it functions in our culture… and what roles it plays in the constructs of power that support the flourishing of some at the clear expense and exploitation of the flourishing of others.”[9]

Dahl created her first all-white art work in 2017, the year before she wrote her essay on whitework. Titled, Whitework: Surrender This Story of Salt (pictured above), it is a white-on-white quilted and embroidered cotton flag, surrounded by thirteen stars meticulously formed of salt crystals installed in a circle on the floor. The flag is sewn with thirteen stripes, recalling the flag of the Thirteen Colonies, and represented to this day by thirteen stripes on the American flag. The work also recalls the first US national flag with its thirteen stripes and thirteen stars. Displayed at sixty-six inches high, Dahl’s flag flies relatively low. Its white-on-white embroidered text is deliberately rendered difficult for viewers to read: the drape of the fabric obscures parts of the text, while the salt stars on the floor prevent the viewer from closely approaching the flag.

Dahl composed the text, which reads: They say she became salt / preserved / forever in a backwards glance / perhaps / she didn’t realize she was doing it / holding so tightly / to all she thought she knew. It loosely refers to the biblical story of Lot’s unnamed wife, who is turned into a pillar of salt. But the artist explains that the work is not so much about sin, but rather what we’re attempting to preserve and what we’re allowing to dissolve. Dahl observes, “It’s very hard for people to let go of the ways that they’re accustomed to living and the benefits that we have and the ability to just not think about the hard things if we want to not think about them.”[10] She is referring to the fact that many white people are hesitant or altogether refuse to acknowledge the privileges that their whiteness affords them, Dahl’s assertions find echoes in sociologist Janet Mawhinney’s foundational writings on the deflection of white privilege, responsibility, and culpability, which she theorizes as “moves to innocence.”[11]

Whitework, Dahl suggests, is work that white people have to do individually and collectively. She asserts, “Although we have the privilege and the benefit of being able to ignore those things… we have a lot to gain in having these hard conversations and really looking deeply at ourselves. And looking at what systemic whiteness does and how our lives are entangled with that.”[12] But she also admits it’s unlikely that white people will wake up in masses and start shifting the way they live. And she acknowledges a need to also be critical of whitework, which “continues to center white people even as it calls on us to relinquish our power.”[13]

Whitework: Surrender This Story of Salt calls attention to whiteness, simultaneously built into the fabric of American society, yet widely suppressed as a structuring element. Created during the first year of the Trump presidency, which was forged in white supremacist xenophobia and during which he famously praised violent white extremists as “good people,” the work connects a throughline from the Trump / MAGA amplification of white grievance and supremacy, back to the country’s very foundations.

Dahl’s experiments with whitework embroidery, as in the sampler above, “opened up this whole way of thinking about a relationship between cloth and whiteness.”[14] Whitework embroidery is highly precise and detail-oriented. To make the stitches, one has to pry apart the holes between warp and weft threads, and pass the needle between and through those spaces. The sampler is where many of Dahl’s ideas and conceptions of whitework—which began with linguistic associations between whitework and white work—first emerged. She observes that she “would not have come to a lot of the metaphors and the ways that I approached the idea of white work without having actually done the work with the needle in hand.”[15]

Dahl also asserts that the only reason she’s able to speak critically about whiteness is because of the work of BIPOC thinkers, writers, artists, and activists like James Baldwin, Tony Morrison, Aram Han Sifuentes, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and Ijeoma Oluo. In her essay that opens this writing, Dahl cites writer Ijeoma Oluo’s description of privilege in white supremacist societies: one group flourishes because another group is structurally suppressed. Using a metaphor of weaving, Dahl observes that if this system was applied to the loom, it would be impossible to weave even the simplest of cloths, because the threads would not be allowed to move freely up and down. White supremacy does not allow for the creation of a whole cloth in which “every thread is afforded agency to contribute to the whole.”[16] When Dahl suggests that “[w]hitework demands that equal attention be paid to the underlying structure of the cloth as to the composition of the stitches applied to it,” she is referring to the social fabric: much as cloth is structured by warp and weft threads, whiteness structures the very fabric of society.[17]

Whitework textiles, whiteness, white supremacy

As Dahl makes material and semantic connections between whitework textiles and white supremacy, I shift here to surveying some historical ones.

In textiles, the term whitework describes a wide range of white-on-white sewn and quilted textiles made using white stitching on a white fabric ground, to create embroidered, three-dimensional, and lace structures and designs. Whitework techniques span drawn thread and pulled-fabric work, corded and stuffed quilting, shadow work, looping, piling, tufting, and fringing.[18] Often said to have originated in Europe, whitework techniques can in fact be traced to Egypt, where drawn-thread techniques are found in embroideries dating to 300-200 BC, and to Persia and the Indian subcontinent.[19] Some of the most sophisticated examples of whitework embroidery can be seen in fifteenth-century Chikankari on the Indian subcontinent, a style likely influenced by white-on-white Shirazi embroidery from Persia.[20] Many styles of whitework emerged in an effort to mimic expensive, high-quality lace from the Indian subcontinent, Italy, and France. In Europe, whitework became popular during the Middle Ages, when the use of color was banned by church edicts forbidding excessive luxury in dress.[21] It was likely then that elaborate, all-white stuffed, corded, and quilted bedcovers came to be produced in countries like France and Italy.

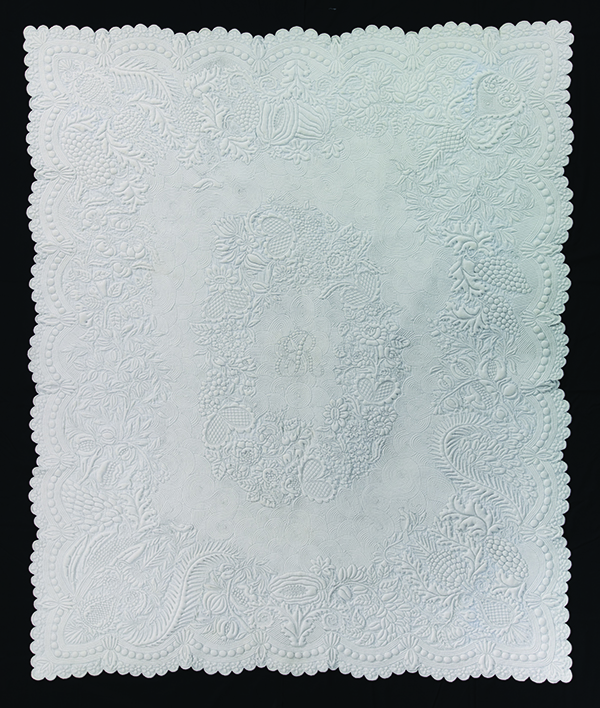

Precolonial trade between Asia, Africa, and Europe facilitated the movement and exchange of textile materials and techniques. The French port city of Marseilles was an historically important site for trade in textiles between Western Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, China, and the Indian subcontinent. Its professional needleworkers were known to adapt fine needlework techniques from diverse parts of the world, to local advantage.[22] Uncoincidentally, Marseilles is where broderie de Marseille (also called Marseilles quilting or Marseilles work), the style of finely corded, sculptural, stuffed and embroidered all-white quilts that bear its name, was created. The ceremonial wedding bedcover pictured below is an example of some of the most exquisite and skillfully rendered all-white Marseilles work of the nineteenth century.

Whole cloth quilt, whitework / Courtepoine de mariage, corded/stuffed cotton, 70 x 58 inches, 1830-1850. Byron and Sarah Rhodes Dillow Collection, International Quilt Museum, University of NE-Lincoln, 2008.040.0157.

Whitework textiles became exceptionally popular in Western Europe and America in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, a development likely spurred by colonization. Colonial exploitation brought profitable access to fine linens, cottons and silks to colonial powers like France, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, and Britain, as it did slightly later in the US The city of Marseilles, for example, was granted exclusive privilege by the French monarchy in 1669 to import fine cotton tax-free from the Indian subcontinent, substantially augmenting the availability of fabrics used to create Marseilles whitework, which in turn made it more widely available, desirable, and popular.[23] Quilt artist and scholar Sharbreon Plummer crucially reminds us that an explosion in American quilting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, prompted by the widespread availability of cotton and cotton fabrics in the US (as elsewhere), was only possible because of enslavement.[24]

Whitework textiles were in extremely high demand in the United States between approximately 1790 and 1900. American women made all-white, whole-cloth quilts, counterpanes, table linens, curtains, frocks, petticoats, dresses, undergarments, and gloves. The most sought-after style was the intricate stitched, corded, stuffed, and sculptural whitework from Marseilles, quilts in particular. These coveted all-white bedcovers were made by highly skilled professional needlework artists and artisans who understood the properties of light and shadow and worked “skillfully in three dimensions.”[25] Each quilt was worked by multiple professional needlewomen and took several hundred hours to complete, making them prohibitively expensive. Only the wealthiest Americans could afford them, and most women had no choice but to make their own. Because Marseilles whitework was so incredibly difficult to achieve, new techniques using embroidery, stuffing, cording, knotting, tufting, looping, and fringing emerged in an effort to imitate them.

Whitework represented the height of fashion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It was common for bed chambers of the time to be all-white, with painted white furniture and white straw matting on the floor. Beds, dressing tables, and windows were covered with whitework linens, quilts, counterpanes, and curtains.[26] Elizabeth Donaghy Garrett, a scholar of American domestic interiors of the period, observes that American literature, advertisements, and magazines were replete “with the imagery of snow-white abundance,” and the linen closet became the standard for judging a housewife’s proficiency.[27]

The American whitework craze was part of a growing emphasis on domestic cleanliness, purity, and personal hygiene as symbolized by the color white. In contrast, Garrett observes, Blackness was associated with a lack of cleanliness, which clearly aligns with anti-Blackness of the time.[28] All-white bedlinens, table linens, clothing, and undergarments had to be laundered frequently. Laundry was done primarily by hand, and the labor required to sew, launder, and care for whitework textiles required substantial amounts of a housewife’s time. Scholar and architect Ana Araujo suggests that the color white was mobilized as a marker of cleanliness and purity to constrain white Victorian-era housewives to the domestic sphere. Maintaining a high level of cleanliness in the home, symbolized by the color white, served to trap them in a cycle of domestic cleaning work, which Araujo describes as a pattern of repetition “of endless duration.”[29]

The popularity of whitework textiles in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries occurred within the context of a larger cultural nostalgia for the color white as part of the larger American neoclassical movement in art, architecture, and interior design. Whitework textiles embodied Greek and Roman ideals of classical beauty and purity, symbolized by the color white. Scholar and curator Stacy C. Hollander asserts that in eighteenth-century America, “the crystalline austerity sought in neoclassical art, architecture, and decorative arts was an ideal that could be captured only in the incorruptibility of whites that directly invoked the transcendence, purity, and timelessness of classical antiquity.”[30] Whitework textiles (like furniture, glass, and ceramics of the period) featured Greco-Roman motifs like wreaths, urns, medallions, florals, vines, cornucopias, and tassels.

Historian Nell Irvin Painter further observes that neoclassicism’s all-white aesthetic derived from classical Greek and Roman statues, which served as an ideal of human beauty, and symbolized the ideal subject or person, who was white. In the eighteenth century, early art historians extolled the beaty of white skin and equated the use of color in sculpture with barbarism.[31] Painter importantly observes that art historical ideals of neoclassical whiteness greatly influenced new theories of racialized whiteness and white supremacy that emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Philosopher Immanuel Kant, the father of modern aesthetics, was also one of the very first to theorize distinct racial hierarchies and white racial superiority. He and other leading theorists of modern aesthetics in art and architecture like Gottfried Semper, Owen Jones, Adolf Loos, and John Ruskin ascribed to white supremacist ideas of Aryanism, defining the white race as superior to other races that they associated with savagery and primitivism.[32] Their writings are permeated by white supremacy, racism, imperialism, Orientalism, and antisemitism, and they remain highly influential today.

White supremacy justified ongoing colonization, enslavement, dispossession, and dehumanization. In the US, white supremacy justified the institution of slavery and made the perceived inferiority of Black Americans a foundational American belief that persists today.[33] White supremacist doctrines like manifest destiny—the belief in the divine right of white Christian Americans to colonize and settle the entire continent—drove westward settler expansion, Native expulsion and genocide, and the conquest of large parts of Mexico. White supremacy was enshrined structurally and systemically by force in every sphere of American society: governance, legislation, institutions, religion, and social and economic structures.

This section examined the place of whitework in a broader context of white supremacy, anti-Blackness, and white womanhood. It is no coincidence, in my analysis, that the overwhelming popularity of whitework textiles in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries occurred during a period when material culture and aesthetics were so seamlessly imbricated with white supremacy. The next section moves to consider Dahl’s works in response to white supremacist doctrines like manifest destiny in Oregon, where she lives and works.

Oregon and Westward Expansion

Dahl has lived on the west coast of North America ever since she was a toddler, in California, western Canada, and now Oregon. The socio-political history of the region is highly influential to her work. Growing up, Dahl recalls, she was rarely encouraged to consider the implications of being a settler on Indigenous lands.[34] Over time, however, she came to better understand that she comes from a background of the colonizer, spurring a shift in her practice toward works that engage more directly with settler colonialism in Oregon.[35] For Indigenous scholar Rachel Flowers (Leey’qsun), the term settler “signifies the settler’s relationship to colonialism . . . . The category of settler is both a structural location and a product of social relations that produce privilege” that “can disrupt the comfort of non-Indigenous people by bringing ongoing colonial power relations into their consciousness.”[36] For Flowers, acknowledging one’s identity as a settler is important, because it means recognizing that one benefits from a system of settler colonialism that persists today; to name oneself as a settler implies a responsibility to oppose and not perpetuate structures of settler domination and privilege.[37] This analysis finds some echoes in Dahl’s works discussed in this section.

Sonja Dahl, Recounting Fragments, solo exhibition at Joan Truckenbroad Gallery, installation view, 2018. Photo by David Paul Bayles.

In a 2018 solo exhibition titled Recounting Fragments, Dahl uses materials that have a relationship to settler culture in Oregon, like salt, linen, cotton, and fabrics produced by the Pendleton Woolen Mills company. Quilts and salt were essential to the settlers’ survival: quilts were necessary for warmth, and salt was used as a preservative to extend the life of food supplies. Comprised of four works that Dahl describes as “quilt-like” objects, Recounting Fragments uses nineteenth century American whitework and pieced quilting techniques. The works draw on patterns and designs used in historical quilts known as Oregon Trail quilts, that were made by white Christian women settlers migrating west along the Oregon Trail between 1840 and 1870, and which Dahl researched extensively. Recounting Fragments features “birds in the air”, “flying geese”, and “delectable mountains” quilt designs that were adopted by women settlers of Oregon as a symbols of westward migration and rootedness in their new homes.

The only all-white work in the exhibit, A Settlement, pictured above, is installed on the gallery floor and it contours the viewers’ movements through the space. It’s comprised of salt crystals, fastidiously arranged to create four quilt-like forms that run along the middle of the gallery floor. In keeping with the artist’s metaphor of whitework as a process and a kind of unraveling of whiteness, the quilt form itself is deconstructed, reconfigured, and reimagined on the floor.

A Settlement combines triangles and arrows commonly found in “birds in the air” and “delectable mountains” quilt designs. These shapes carry meaning in the Oregon Trail quilts. Triangles symbolized movement and referenced pine trees. They were used as emblems of a new home in the west and to indicate rootedness. Arrows also symbolized rootedness. In A Settlement they merge into one another to point in multiple directions.

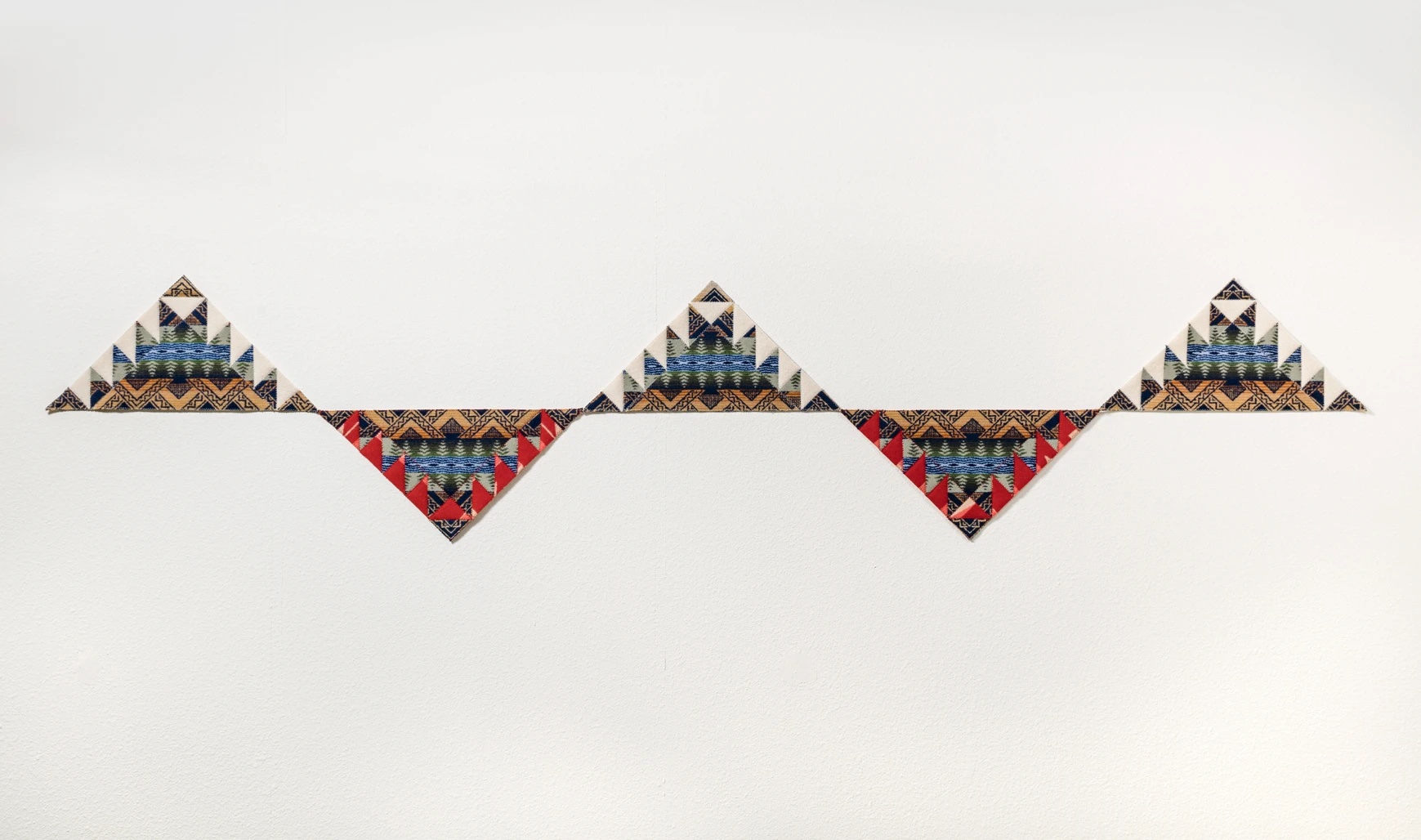

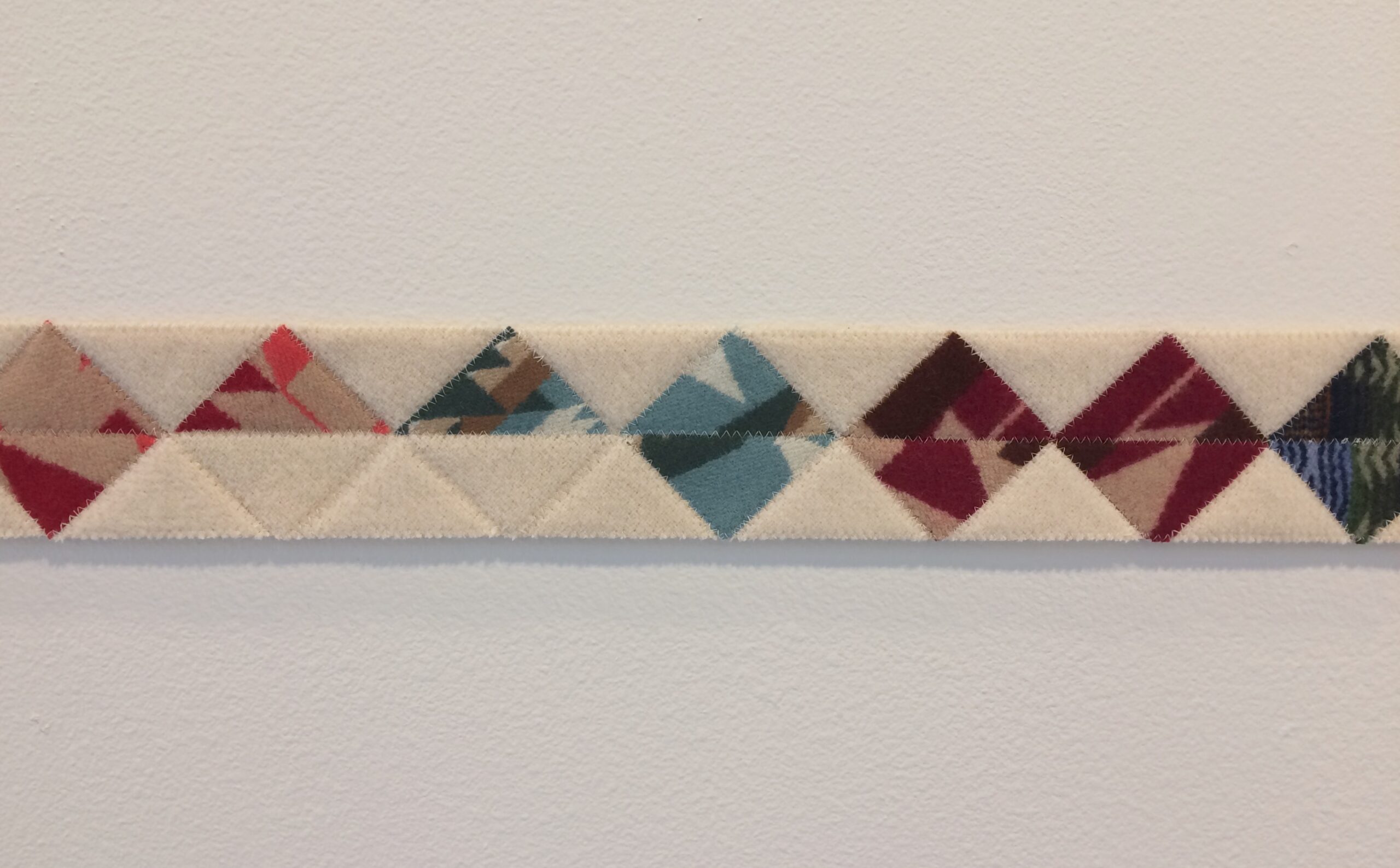

Sonja Dahl, The Delectable Mountains, Pendleton woolen fabric and blanket, cotton muslin, thread, 17″ x 82″, 2018. Photo by David Paul Bayles

The Delectable Mountains (pictured above), is pieced from triangles cut from Pendleton fabrics patterned with trees and waterways, a reference to Oregon’s natural landscape as celebrated in numerous Pendleton fabrics and designs. The work is named for the “delectable mountains” quilt design, created around 1812 and commonly found in Oregon Trail quilts. It takes its name from a passage in the 1678 book Pilgrim’s Progress, a biblical allegory written by the English minister and Puritan Christian preacher John Bunyan. The passage tells the story of pilgrims on their journey to reach the promised land, which is symbolized by the Delectable Mountains. The design became especially popular among settlers along the Oregon Trail, who saw themselves as Christian pilgrims who relied on their faith to help guide them to Oregon, a land they believed was given to them by god. The quilt design celebrates the sight of the mountains coming into view in the distance, which meant that the promised land was not much further away.[38]

Dahl’s “mountains” point upward and downward in alternating directions. A similar strategy is used in the adjacent work A Settlement, whose arrow-like forms also point in opposite directions. Both works suggest simultaneous directionality that may be read as east and west, north and south, up and down, back and forth, past and present—with neither a fixed beginning nor an end. As such the works recall the late historian and decolonial scholar Patrick Wolfe’s assertion that, “Settler colonizers come to stay: invasion is a structure not an event.”[39] For Indigenous scholar J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, settler colonialism is “an ongoing genocidal project.”[40] But she also pushes back against white supremacy’s dangerous myth of Native disappearance, the idea that Native peoples no longer exist here. This assertion is itself a symptom of settler colonialism—as Wilson Wewa, a Warm Springs washat leader asserts, “We are still here.”[41]

Here it’s crucial to note that quilting and needlework were deployed as part of genocidal and assimilationist practices in the seventeenth through twentieth centuries. Sewing and quilting were taught in Christian missionary schools and US government-run boarding schools that took millions of Native children away from their families and assimilated them in a deliberate attempt to destroy Indigenous communities, languages, cultures, and traditions. Violence, physical, sexual and emotional abuse were rampant in the schools, which are now recognized as one of the US’s genocidal practices against Native Americans.[42] Girls were taught sewing, quilting, and other domestic skills to keep the schools running and prepare them for adult lives as servants. Unpaid child labor was standard practice, as girls had to sew garments and home textiles and make quilts that were sold to enrich the schools. They were often punished and beaten for any imperfections in their work.[43] Today Indigenous quilters like Susan Hudson, a member of the Kin Yaa aanii (Towering House People) Clan of the Navajo Nation, use quilting to depict the violence unleashed upon Native Americans and tell powerful stories of ancestors, healing, resistance, and survival.[44]

Sonja Dahl, Border Cipher, Pendleton woolen fabric and blanket, cotton muslin, thread, 2.75″ x 119″ and 2.75″ x 105″, 2018. Photo by David Paul Bayles.

Dahl’s work Border Cipher (above) is comprised of two long, narrow works pieced from Pendleton woolen fabrics and installed one above the other on the wall. The word “Cipher” in the title refers to a code or disguised way of writing, and the work reconfigures a “flying geese” quilt design as the dashes and dots of morse code to spell out two encoded messages:

— — – …. . .-. / — ..-. / . -..- .. .-.. . … mother of exiles

— .- -. .. ..-. . … – / -.. . … – .. -. -.– manifest destiny

Like other works in the exhibition, Border Cipher is cut and assembled from two types of woolen fabrics produced by Pendleton Woolen Mills: a solid cream wool blanket that Dahl found at an antique store, and patterned fabrics from the company’s mill end store in Portland. The latter are patterned with evergreen trees, forests, and mountains—icons of Oregon’s landscape as captured in the company’s designs. Pendleton fabrics, home furnishings, and garments feature landscapes, plants, and animals found in Oregon, California, and the American southwest. The company claims that its products carry “the spirit of the West” and its designs have names like “Pacific Wonderland,” “Gather,” “Lost Trail,” and “Journey West,” with many others named after landmarks and national parks.[45] Many Pendleton designs feature Native American-inspired imagery and have names suggesting connections to Native American cultures, like “Many Nations,” “Elders / Circle of Life,” “Big Medicine,” “Prairie Rush Hour,” and “Buffalo Nation.” The company was established by English settlers in 1909 in Pendleton, Oregon. It remains a white-owned private company that for most of its history appropriated Native American designs without compensating Native artists or communities. Pendleton only began hiring and collaborating with Native American artists and designers in the 1990s. Today it continues to profit massively from designs that suggest a connection to Native American visual cultures.[46]

One can see in Pendleton fabrics an idealized vision of the West, one that recalls the settler colonial myth of a terra nullius or empty land as a desired site for settlement. The doctrine of terra nullius has been invoked to invisibilize, dehumanize, displace, and render disposable Indigenous inhabitants in settler colonies like the US, Canada, Australia, and Israel. This myth cast Oregon (and the rest of the American West) as a wilderness awaiting migration.[47] David G. Lewis, an anthropologist and enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, asserts that the depiction of pioneers as “a heroic group of people who struggled to reach Oregon, where they tamed the forests, prairies, and savages of the frontier” serves as a powerful trope that obscures the reality of what Native Americans were forced to endure.[48]

Oregon was conceived as a whites-only territory from the earliest days of its settlement, with a legal and political regime based on white supremacy.[49] Native treaty rights were repealed, and land granted to every white settler in the Oregon territory. Black Americans were forbidden by law from entering or residing there. As Portland-based public scholar, educator, and writer Walidah Imarisha observes, “Oregon was founded on the notion of creating a racist white utopia and on the removal, exploitation, or exclusion of all people of color.”[50] Its state constitution, adopted in 1859, forbade Black and mixed-race Americans from citizenship, residency, and owning real estate. In the ensuing decades, Oregon further limited suffrage and citizenship to white men, passed laws banning interracial marriage, and enacted laws to restrict the rights of Chinese and Hawaiian immigrants from residing in the state. Its elected representatives to Congress influenced American immigration policy and successfully pushed for exclusions in the Immigration Act of 1870 that barred people of Asian descent from becoming American citizens. Oregon rescinded its ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868, and did not re-ratify it until over a century later, in 1973. It wasn’t until 1959 that the state finally ratified the 15th Amendment.

Sonja Dahl, Recounting Fragments, solo exhibition at Joan Truckenbroad Gallery, installation view, 2018.

For Dahl, art can help expose oppressive systems and structures like whiteness and settler colonialism, and she hopes her work can create spaces for reflection and even conversation. Her work often relies on the comfort of quilts as familiar domestic objects, to invite viewers into conversations they may not have otherwise. Quilts, Dahl notes, are approachable and many viewers are familiar with their designs, which is helpful when trying to open up challenging conversations. Dahl chooses to show the quilt works discussed in this section more locally in Oregon, where viewers recognize the Pendleton fabrics and can respond more intimately to the source materials and designs in the works. This can serve as an entry point to “help spur people who haven’t really been considering those things to think about the colonial settling of Oregon.”[51]

CONTENT WARNING: The following section, “Quilting white supremacy,” contains images of quilts made in support of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan.

Quilting white supremacy

Quilts and whitework quilting are generally not discussed as vehicles for upholding white supremacy. Yet quilting practices have at times played a crucial role in advancing white supremacist doctrines and causes. This section looks to quilts that explicitly and implicitly advance white supremacy.

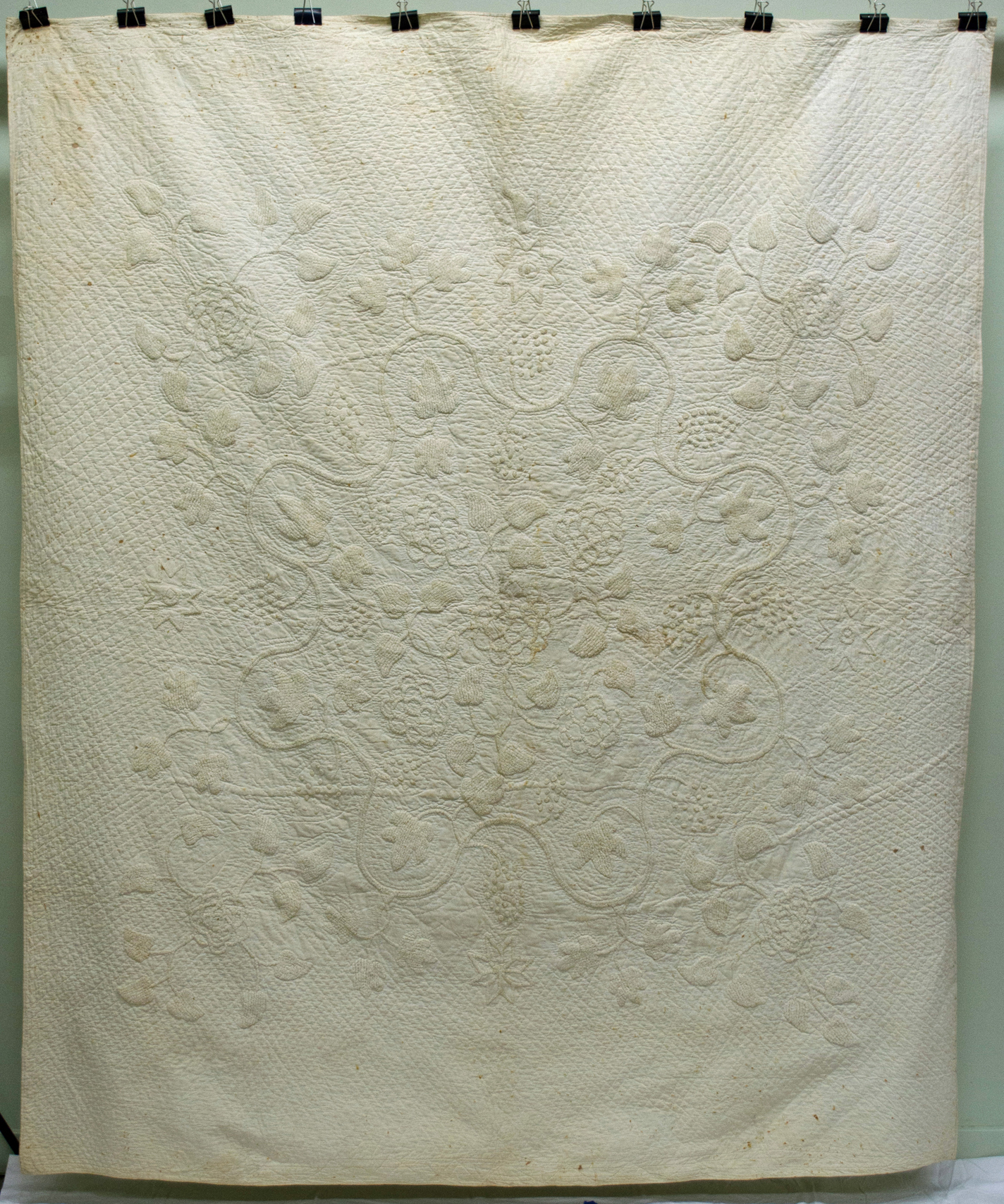

Tufted White Whole Cloth by Mary Green Scoggins Chambers, Cotton, broadcloth, 73″ x 86 1/2″. Courtesy the Lane County History Museum.

While the great majority of Oregon Trail quilts were pieced, one surviving example of a whitework quilt is illustrated above. Fascinatingly for the purposes of this writing, it is the earliest quilt connected to the Oregon Trail. The quilt is a whole cloth, white-on-white embroidered, tufted, and quilted bedcover. Its motifs are consistent with the neoclassical designs discussed earlier. It was made using a candlewicking technique, named for the bulky, candlewick-like plied cotton yarns used to create three-dimensional, looped, fringed, and tufted pile designs that are characteristic of mid-nineteenth century American whitework quilts.[52] The technique was invented in the US, and some quilters attribute its creation to westward expansion, when women settlers used actual candlewicks in their quilts.[53]

Oregon-based quilt scholar Mary Bywater Cross provides the most comprehensively researched account of the quilt and the woman who made it, a white Christian woman named Mary Green Scoggins Chambers.[54] Her Irish ancestors settled in Rhode Island prior to 1700, and the family relocated to Kentucky, where Mary was born, in 1809. She married a man from Tennessee and moved with him to Missouri in the 1830s. Mary was widowed, and re-married in 1844, migrating along the Oregon Trail with her family and settling in Oregon in 1845. Cross’s research reveals that Mary’s father-in-law was a plantation overseer, and her mother-in-law was an aunt to president Andrew Jackson, a slave owner who fought for the expansion of chattel slavery in the western territories.[55] Jackson’s top legislative priority was to expel Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the American South to make way for white settlers and enslavers to cultivate cotton on Indigenous lands. As President he signed the genocidal 1830 Indian Removal Act.

The quilt is an early artifact of westward settlement to Oregon, and an example of the material culture of the Oregon Trail. Quilting was an important part of preparing for western settlement. Some quilts were gifted to women settlers by family members and friends to accompany them on their journeys and remind them of loved ones back home. Many more quilts were made along the way. By virtue of their motifs and designs that symbolize westward migration and celebrate rootedness in Oregon, Oregon Trail quilts can be said to embody white supremacist ideologies like manifest destiny. Historian and journalist Matthew Dennis observes that domestic activities like quilting served to depict white women settlers to Oregon like Mary Chambers as “passive and traditional emblems of domestication and reproduction,” and this depiction “helped characterize the colonial process as tender and peaceable, obscuring its aggressiveness and violence.”[56]

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, white Christian women participated robustly in white supremacist organizations and causes, often turning to quilting to help finance them. During the Civil War for example, white Southern women wove homespun textiles and made quilts, uniforms, coats, clothes, socks, scarves, gloves, and bandages for Confederate soldiers. Notably, they made quilts that were sold or raffled off to raise funds to pay for munitions, gunboats, and other military supplies for the Confederate army. Historian Tom Vincent calls the mobilization of women’s traditional roles to support the Confederacy “war work”.[57] But war work wasn’t limited to the domestic sphere, or to textiles: white women founded Confederate Soldiers’ Aid and Ladies’ Clothing associations, assumed public roles, and participated in the military effort, spying for Confederate authorities and carrying medicines through battle lines.[58] Many were celebrated as war heroines.

After the Civil War, white Southern women played a crucial role in memorializing a society built on white supremacy, anti-Blackness, and enslavement. They used their needlework skills to celebrate the Confederacy, sewing memorial samplers and quilts that glorified the Confederacy and commemorated its leaders. Many quilts are inscribed with Confederate flags, symbols, and slogans. Some incorporate fabrics cut from uniforms worn by Confederate soldiers, while others include photos of Confederate leaders printed onto the quilt fabrics.[59] Immediately after the end of the Civil War and for decades afterward, white Southern women formed powerful Ladies Memorial Associations (that later merged into the United Daughters of the Confederacy) to actively fundraise for Confederate causes. They mobilized their sewing and quilting skills to raise funds for Confederate monuments and memorials. In North Carolina for example, the state’s first ever Confederate memorial was funded through the raffle sale of a quilt. Spearheaded and designed by a schoolteacher and seamstress, a patchwork quilt was made in 1865 in Fayetteville, North Carolina by women and girls who sewed the three thousand individual silk and cotton squares that comprise the quilt.[60] Three hundred raffle tickets were sold for one dollar each, raising the funds to pay for a Confederate memorial, erected in the town in 1868.

White Christian women also quilted in support of the Ku Klux Klan. All of the known examples of Klan-related quilts were created in the 1920s, when the KKK expanded beyond its historical base in the South to gain popularity nationwide, especially in the West and the Midwest. Oregon was a hotbed for the KKK in the 1920s, becoming home to the largest Klan organization west of the Mississippi River. By 1923, Oregon had the highest Klan membership per capita, second only to Indiana. The organization’s leaders saw fertile territory for expansion into Oregon, a state that was ninety-five percent white, eighty-five percent Oregon-born, and majority Protestant. Like other hate groups, the KKK flourished because it was able to offer a sense of community and united purpose, made possible thanks to Oregon’s “favorable demographics and preexisting racist and xenophobic attitudes.”[61] Today white extremist groups continue to operate there.

It is estimated that between three and six million white Christian Americans joined the Klan in the 1920s, a period that saw increased white supremacy, anti-Blackness, and xenophobia triggered by immigration and the Great Migration. White Protestant women flocked to the Klan in large numbers in the 1920s. They had their own organization, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), “a strictly Protestant Christian organization of native-born white American Women,” with chapters in every state in the country.[62] The WKKK opposed racial equality, immigration, Blacks, Jews, Catholics, Mormons, socialists, labor activists, parochial schools, and “moral decay” as part of a female crusade for a white nativist America that mixed white Protestant nationalism, moral purity, and virulent xenophobia. The WKKK was one of the largest, most influential right-wing women’s organizations of the period.[63] As sociologist Kathleen M. Blee asserts, “in the 1920s, the activities of Klanswomen, commonly dismissed as inconsequential and apolitical, were responsible for some of the Klan’s most destructive, vicious effects.”[64]

To date there are three known KKK quilts, though scholars suspect that many more were created. Some are likely still kept as family heirlooms; others may still remain hidden; some may also have been destroyed. For quilt scholars Marsha MacDowell, Charlotte Quinney, and Mary Worrall, it’s surprising that more KKK quilts haven’t surfaced. They surmise that many quilts may remain in the possession of individuals and families who want to distance themselves from a connection to the KKK.[65] As historian Katherine Lennard observes, Klan artifacts are simultaneously ubiquitous and elusive.[66]

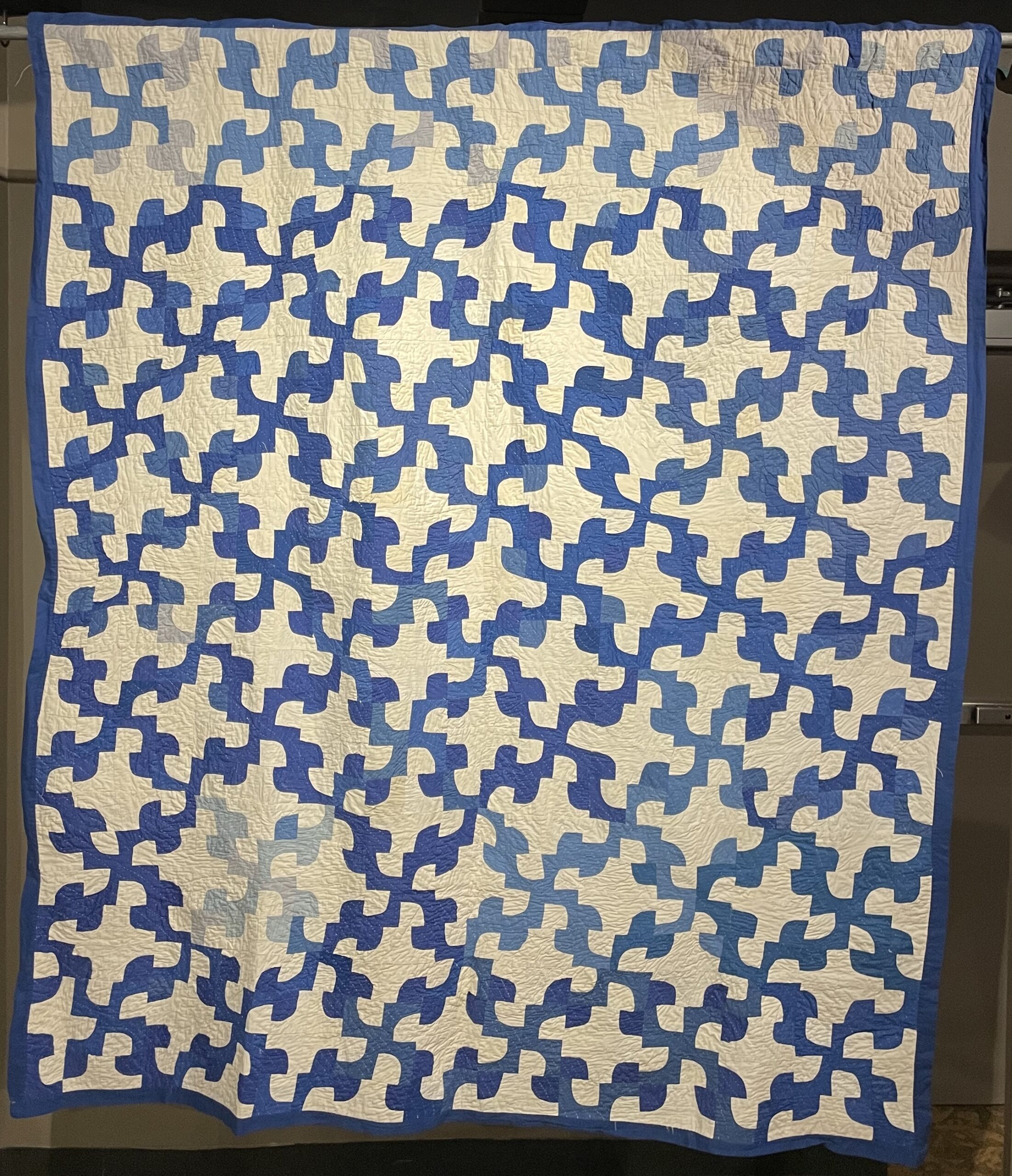

All three KKK quilts were donated to museum collections for educational purposes. They were all made in the two-color, white-and-blue or white-and-red styles that were popular in American quilting of the 1920s, but with differences in style. One quilt is sewn in a more abstract “Drunkard’s Path” design and therefore unlikely to visually present as a Klan quilt, while the other two are recognizable as quilts created explicitly for the KKK. All reveal information about Klan activity and white Christian women’s involvement in it.

The Drunkard’s Path Quilt (pictured above) was made in Pullyap, Washington in 1928. It was assembled from blue and white fabrics in a Drunkard’s Path pattern by a woman named C. C. Parmeter. The topstitching is hand sewn. The quilt is worn, with stains, indicating use. The Parmeter family was involved with the Klan. The white fabrics used in the quilt were cut from Klan masks worn by area Klan members. It’s possible they belonged to Mrs. Parmeter’s husband or another male family member. It’s also possible they belonged to Mrs. Parmeter herself, as members of the WKKK were outfitted in their own Klan robes and hoods.[67]

The quilt was donated to the Yakima Valley Museum in 1978 by an anonymous donor, accompanied by a typewritten note that reads:

You may not want to use this information but I shall write it down anyway just in case you may want it. The white parts of the quilt are made from the masks of the robes worn by the K. K. K. The masks were discarded from their costumes at a torch lighting parade in Olympia. I’m guessing about the date on that but it must have been 1927 or 28. The State of Washington was teeming at that time with this organization. Some of the “big brass” of the Police Force in Puyallup were solid members, and seemed to be the backbone of the lodge.[68]

The note is also anonymous. Lennard asserts that the discarding of Klan masks coincided with a 1928 national edict for Klansmen to unmask, and so the quilt could be a fascinating document of Klan leaders’ attempts to make their organization seem more respectable.[69]

Repurposing worn out garments and fabrics into quilts is a common practice to give them new life while also preserving them. Similar strategies were deployed in the Confederacy quilts discussed earlier, which can incorporate Confederate uniforms worn by the quilt makers’ husbands and relatives. It’s possible that Parmeter similarly created her Klan quilt to honor and commemorate her family ties to the Klan. Her motives will likely never be known, but there’s no doubt she used Klan hoods—one of the ultimate symbols of violent white supremacy—to create an object of warmth and comfort for herself and her family. The quiltmaker’s daughter confirmed the family’s involvement with the KKK, noting that she had her own robe as a child for parades and was a “‘mascot’ of her family’s group.”[70] The quilt attests to the embeddedness of the Klan and its violent, xenophobic, white nationalist ideologies within communal and family structures, and to white Protestant women’s roles as active progenitors of its doctrines.

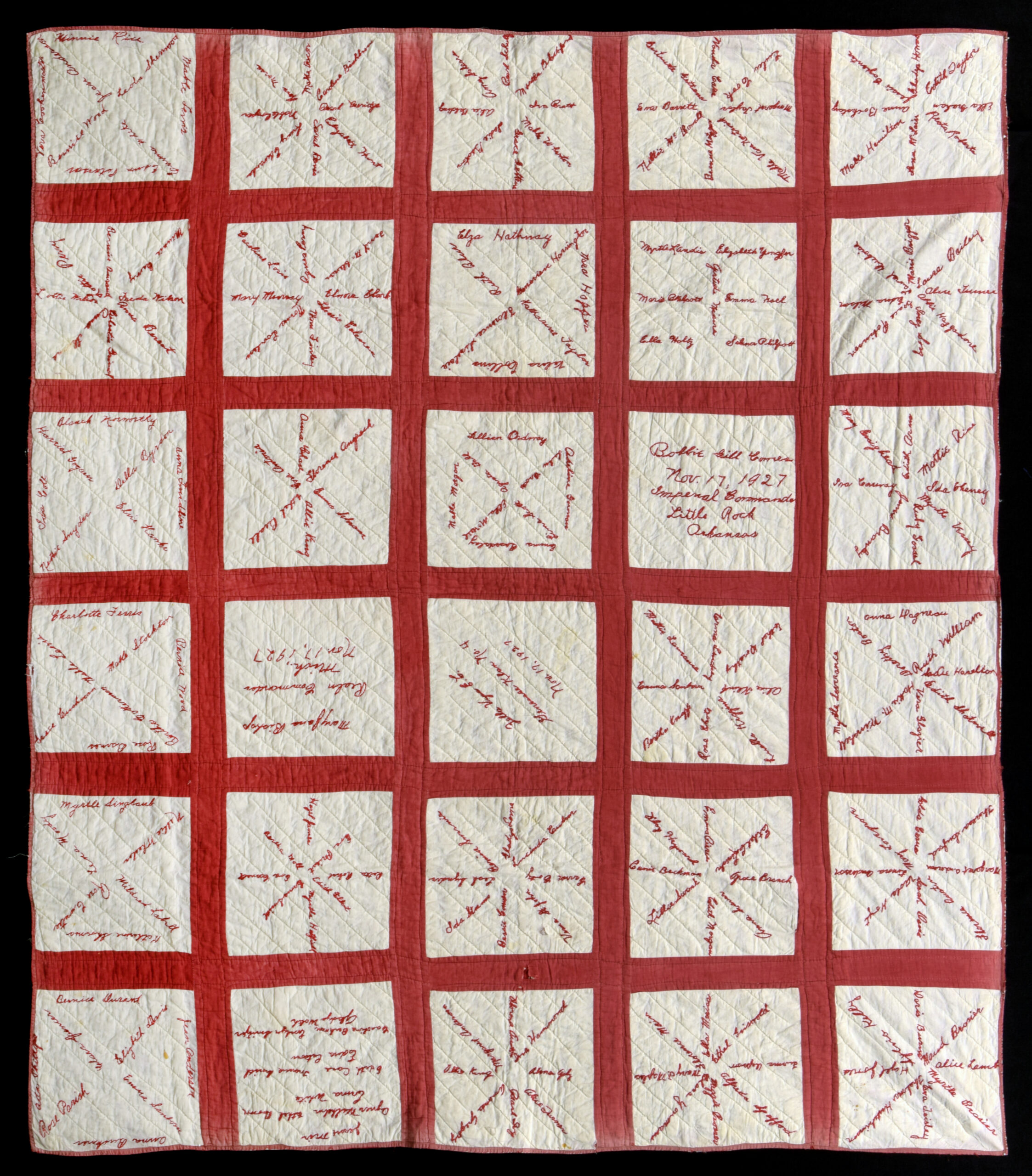

Emma Noel, Women of KKK, Genesee County, red and white signature quilt, Cotton, machine pieced and hand quilted, 1927. Accession number: 2016:58.1. Courtesy of the Michigan State University Museum.

Two other examples of KKK quilts—known as Women of KKK, Genesee County and Ku Klux Klan Fundraising Quilt—were created in Michigan. The quilts are both sewn in a “signature” style with individual names hand embroidered in red thread, in a style known as red turkey work. Women of KKK, Genesee County (pictured above) was created in Flint, in Genesee County, Michigan, by a Norwegian-American woman named Emma Noel. It is inscribed with “Genesee Klan No. 4,” and MSU Museum records state that the quilt was made as a signature or friendship quilt for the women of Genesee Klan No. 4. By my count, there are approximately 206 names on the quilt, probably all members of the WKKK. Two of the quilt blocks honor high ranking leaders of the WKKK—the Realm Commander or leader for the state of Michigan, and its highest national leader, the Imperial Commander, based in Little Rock, AR where the WKKK was chartered. The quilt may also have been sold to raise funds for the Genesee Klan No. 4.[71] Whereas the Drunkard’s Path Quilt attests to one woman’s family connections to the KKK, the present Women of KKK, Genesee County quilt provides insight into women’s robust participation as active members and leaders. So, too, does the quilt discussed below.

Ku Klux Klan Fundraising Quilt, pieced signature quilt made in Chicora, MI, 1926. Accession number: 2000:71.1. Courtesy of the Michigan State University Museum.

The Ku Klux Klan Fundraising Quilt (pictured above), was created in 1926 in Chicora, MI to raise funds for the KKK. It is inscribed with “Chicora, K.K.K. 1926” and “K.K.K. 77” which indicate the “Klavern” or local branch of the KKK. The quilt is comprised of blue and white fabric blocks featuring a cross as a central motif. One block is embroidered with a hooded Klansman holding a cross and riding a horse. These blocks are interspersed with signature-style blocks inscribed with over two hundred names, many of them names of married couples. Each individual paid ten cents to have their name embroidered on the quilt, which was subsequently raffled off to support the local K.K.K.

The quilt was collectively made by dozens of white Protestant women of English, German, Dutch, and Anglo-Saxon ancestry.[72] The Ku Klux Klan Fundraising Quilt brings together the contributions of many individuals sewing together to raise funds for the Klan. Chicora is a tiny unincorporated community in rural Michigan, and the fact that it had its own local chapter attests to the KKK’s reach in Michigan. It’s estimated that in the 1920s one in ten people, or as many as 875,000 people, were members of the Klan in Michigan.[73] According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, today Michigan still ranks among the states with the most extremist groups.[74]

White women played an active role in white supremacist organizations and causes, beyond quilting in support of the KKK. The attainment of suffrage for white women in 1920 brought voting power and the assumption of new and influential roles in American society, in social, political, economic, educational, and cultural spheres. White women used their votes, platforms, and positions as mothers, wives, teachers, nurses, social workers, and political organizers to form segregationist organizations and help bureaucratize white supremacy in social welfare policy, public education, electoral politics, and popular culture.[75] Fomenting anti-Blackness was central to their efforts to uphold white supremacist politics. As historian Elizabeth Gillespie McRae observes, white women played a crucial role in enforcing racial segregation and opposing all prospects for racial equality throughout the entire United States in the 1920s through 1970s. They also played (and continue to play today) a leading role in right-wing political organizing and advancing conservative agendas against immigration, abortion, equal rights, and same-sex marriage. Today white Christian women wield incredible social, financial and political clout on the far right, as politicians and elected representatives, bloggers and media personalities, militia members, grassroots activists, and organizers with extremist groups like QAnon, the Oath Keepers, and Women for America First (the organization that held the permit for the march that became the January 6 insurrection).[76] White women are instrumental in advancing white supremacist efforts to ban books and the teaching of African-American history and critical race theory, and in pushing homophobic and transphobic anti-LGBTQIA agendas and legislation, thanks to so-called parental rights groups like Moms For Liberty, which is considered an extremist hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[77]

Commemoration, ideology, and systems of representation

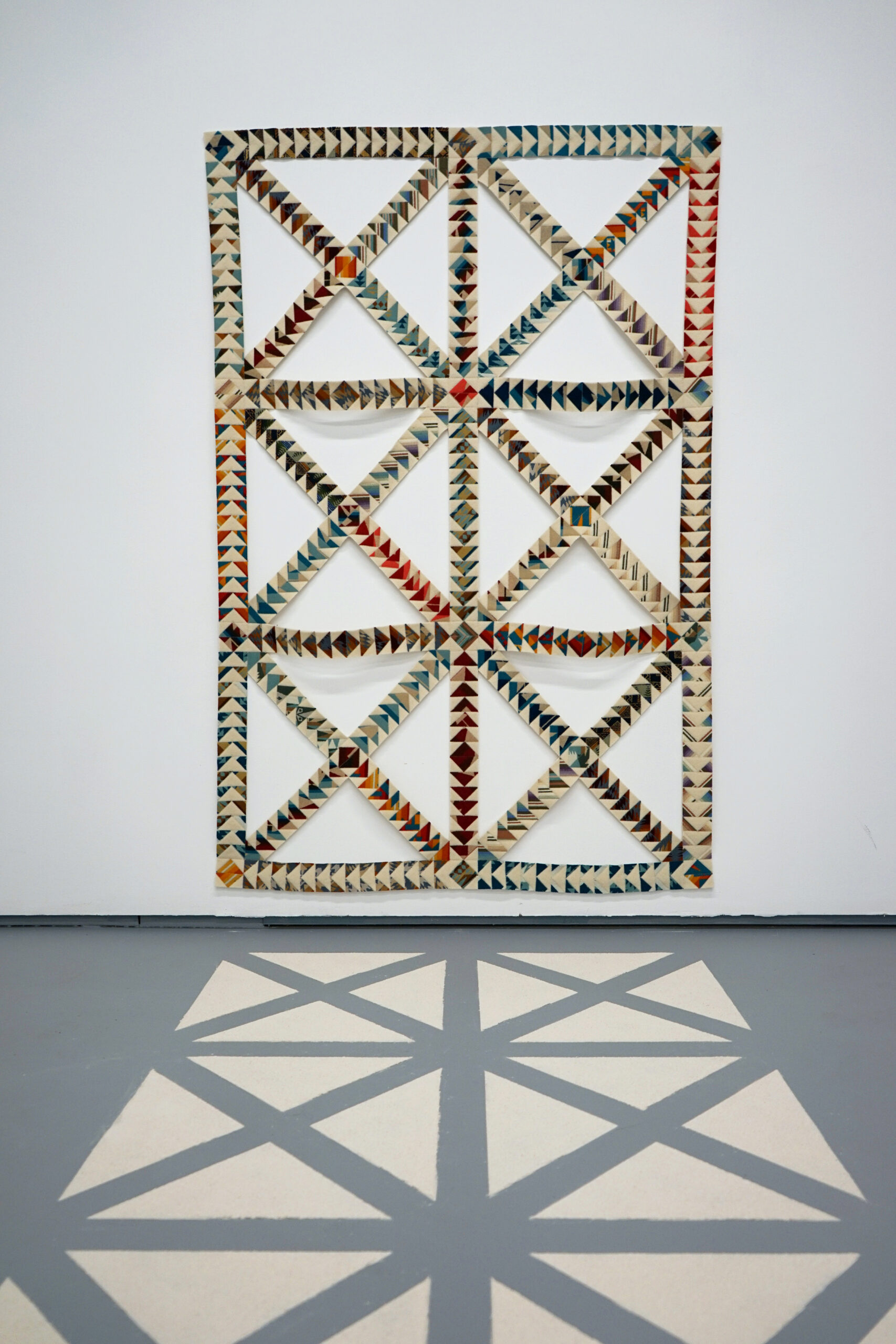

Sonja Dahl, Interstices, Pendleton woolen fabric and blanket, wool felt, thread, flour, 71” x 48” (dimensions of the wall hanging), 2022

The year 2020 brought months of catastrophic forest fires to Oregon. Repeated climate disasters have shifted Dahl’s relationship to her adopted state of Oregon. She says she can’t help but think about fire and the very real impact of how settler colonialism changed the ways that humans interact with the natural world in Oregon.[78] Dahl’s recent works connect Oregon’s settler culture to resource extraction, massive environmental destruction, and forest fires. Interstices (depicted above), is one such work.

Interstices is a complex feat of quilt engineering, a deconstructed form comprised of triangles assembled into strips that create quilt block-like patterns and shapes—squares, diamonds, triangles and stars—through the use of lines and empty spaces. Here again Dahl employs Pendleton fabrics, deployed in a “flying geese” quilt design. The color white also recurs in both the fabrics and the triangle shaped quilt “blocks” created from flour installed on the floor, “as the negative spaces that fell out of the quilt.”[79]

It was exhibited in 2022 as part of the group exhibition Quilt Bloc at Ditch Projects in Springfield, Oregon, organized in collaboration with the Springfield History Museum. Works by contemporary artists were paired with historical quilts from the Museum’s collection, connecting past and present material histories and teasing apart dominant historical narratives. Their juxtaposition “amplifies what is visible and reveals what is present in the gaps.”[80] Dahl was especially interested in the notion of gaps.

Dahl’s work was paired with a quilt made by local quilters in 1985 to commemorate the centennial anniversary of Springfield’s incorporation as a city. In it, a central image depicts a scene from the town’s idyllic past, with mountains, a river, a covered bridge, salmon, eagles, evergreen trees, flowers, and animals. Springfield was a mill town, and one also sees a mill, trees, logs, and stacks of wood. The central, figurative imagery is surrounded by all-white quilted areas, together with brown and white signature blocks presumably inscribed with the names of the volunteers who created the quilt. Fascinatingly, the all-white fabric areas of the quilt are sewn in a historical whitework quilting style, with topstitched vine motifs reminiscent of nineteenth-century neoclassical all-white quilts.

One sees in Interstices very similar (albeit abstracted) elements to those in the commemorative quilt: white materials (fabrics and flour), idyllic images of the past (captured in the Pendleton fabrics), and histories of material extraction. Springfield’s economy was sustained primarily by the logging industry for decades until the 1990s, when its mills were forced to close due to years of over-aggressive logging practices. Ditch Projects is housed in a former logging mill complex, located on Indigenous Kalapuya Ilihi lands. While the commemorative quilt is celebratory, Dahl’s is perhaps more dystopian. The “flying geese” that have historically symbolized movement and migration are instead trapped in an endless loop within a singular frame. The structure is precarious. It is a metaphor for whiteness, for white supremacy, for settler colonialism, that all rely on unstable structures to perpetuate them and prop them up.

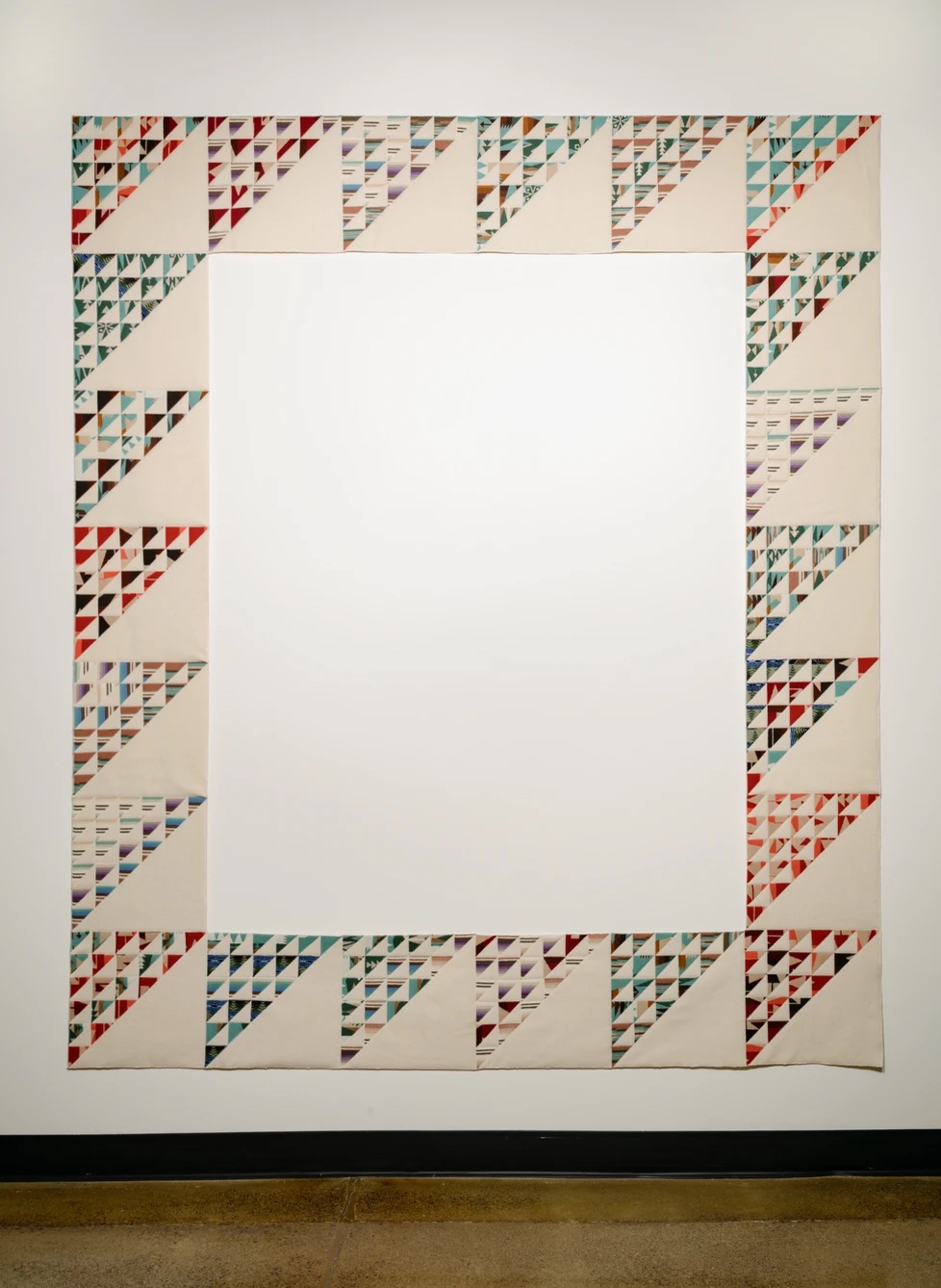

Sonja Dahl, Implicate: Incomplete, Pendleton woolen fabric and blanket, cotton muslin, thread, 83″ x 71″, 2018. Photo by David Paul Bayles.

Interstices harkens back to the fourth work that comprised Dahl’s 2018 Recounting Fragments exhibition. Implicate: Incomplete (pictured above) was also included in the show at Ditch Projects. The work takes the form of an empty, quilted frame. It speaks to the omnipresence of whiteness and white supremacy: always framing everything, yet suppressed and denied by so many of those who benefit from it.

For philosopher Louis Althusser, “ideology is the system of the ideas and representations which dominate the mind of a man [sic] or a social group.”[81] The function of ideology, for Althusser, is to reproduce existing relations of production under capitalism—to reproduce submission. Individuals must be equipped to respond to the needs of society, and this is achieved through what Althusser calls interpellation, or hailing. Put reductively, interpellation is a social process through which we learn, internalize, and are assimilated into ideologies. Interpellation is subconscious: the ideologies into which we are hailed are not consciously recognized, and we are marked by interpellation before we are even born.

Postcolonial theorist Stuart Hall offers a helpful reading of Althusser. Hall notes that ideologies are frameworks for thinking about the world—ideas people use to figure out how the social world works, and what their place in it is.[82] I turn here to Hall because he emphasizes systems of representation, read through a poststructuralist lens shaped by his own discursive and embodied understanding, as a Black, British, Jamaican-born man, of how ideologies of colonialism and race shape subjects and lived experiences. Hall takes up questions of representation in Althusser’s canonical text on interpellation, in which Althusser suggests that “[i]deology represents the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.”[83] For Hall, systems of representation are systems of meaning through which we represent the world to ourselves and each other, and it is through them that we experience the world. Like ideologies, systems of representation are founded on unconscious structures that we are not necessarily aware of.[84] Following Althusser and Hall, we are all interpellated into white supremacy, albeit in very different ways depending on whether one benefits from whiteness or not.

But Hall diverges from Althusser to assert that ideologies can shift and be transformed over time. Ideology “becomes a site of struggle” when “people try to displace, rupture, or contest it by supplanting it with some wholly new alternative set of terms, but also when they interrupt the ideological field and try to transform its meaning by changing or re-articulating its associations.“[85] Through her art practice, Sonja Dahl aims to achieve this transformation of meaning. She is harnessing the language and material culture of historical quilts and whitework textiles—objects that are inextricably bound up in white supremacy as outlined in this writing—and encoding them with counter-hegemonic messages and meanings. She is using them to destabilize and interrogate dominant histories through deliberate slippages, juxtapositions, and ruptures that are at once material and discursive.

Is whitework an effective, large-scale strategy for reversing centuries of white supremacy? It is not, and it’s also not intended as such. But it is a way of taking responsibility for one’s position in the world, especially when that position comes with the incredible privilege that whiteness affords. And it is a cultural process through which white people can untangle themselves from complicity with whiteness and actively work to overthrow white supremacy.

Conclusion

Our contemporary moment of white anger, resentment, and grievance is not an exception, and it is also not new. Rather it is part of a long historical trajectory of white supremacy and violent backlash to gains made by Black, Indigenous, and people of color—and Black Americans in particular.[86] Dahl’s works provide context for white Americans to consider this historical trajectory and their own place in it, asking them to examine the psychological hold that white supremacist ideology has on them.

In a series of public videos and Instagram posts created in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, author and activist Sonya Renée Taylor analyses white supremacy as a system based on widespread delusion into which we are all indoctrinated, and she challenges white people to renounce their delusion and acknowledge all of the perks that whiteness brings. Scholar, activist, and professor of Black Studies Kehinde Andrews invokes psychosis as a metaphor for how whiteness operates. Psychosis is a psychological disorder characterized by delusional thinking and hallucinations, “which are believed as real to maintain the psychosis.”[87] This produces a distorted view of reality despite overwhelmingly contradictory evidence. Whiteness is a psychosis, Andrews asserts, because it is based on irrational beliefs of white supremacy while simultaneously denying its existence.[88] This produces delusions and detachment from reality in an effort to maintain white supremacist political, economic, social, and cultural systems. The psychosis of whiteness is not, however, about individual white people. Rather it describes systems and structures across governance, politics, public policy, historical narratives, the media, academia, and cultural institutions worldwide. Black and Brown people can also suffer from the psychosis of whiteness: they are much more likely to suffer mental health issues and be diagnosed with a psychosis as a result of living in white supremacist societies.[89] Whiteness, Andrews asserts, is so deeply irrational that none of us should be engaging with it. Instead, we must work to get rid of white supremacy and create global political and economic alternatives.[90] He cites Black consciousness, Black feminism, and Black radical thought and politics as models for transforming the world.[91]

Whitework is but one of many approaches to divesting from white supremacy. Originally crafted by Dahl with an audience of white Euro-American academics in mind, whitework can open up possibilities while being aware of its own limitations. Whitework, Dahl hopes, will “grow from little accumulating acts of treason” that can rearrange the structure of the cloth, the fabric of society, one stitch at a time.[92]

***

Original research for this essay was conducted at the Michigan State University Museum, the American Civil War Museum, The DAR Museum, the Smithsonian Museum of American History, and at Sonja Dahl’s studio in Eugene, Oregon.

With thanks to Robin Myers, Curator of Collections at the Lane County Historical Society; Michael Siebol, Chief Curator of Collections and Archives at the Yakima Valley Museum; Sarah Walcott, Collections Manager at the International Quilt Museum; Lynne Swanson, Cultural Collections Manager, MSU Museum; Sonja Dahl; Sara Clugage; Faculty Enrichment Funds at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; and the Center for Craft.

This research was supported by a Craft Research Fund grant from the Center for Craft.

[1] W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, “Of the Culture of White Folk,” The Journal of Race Development 7, no. 4 (1917), 440. The term “woof” derives from the Old English term for weft.

[2] Heidi Safia Mirza, Black British Feminism: A Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 1997), 3.

[3] Charles W. Mills, Blackness Visible Essays on Philosophy and Race (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 75. [italics in original].

[4] Sonja Dahl, “Whitework: The Cloth and Call to Action,” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings (2018), n.p.

[5]Building on the citations in the epigraph, whiteness is a system that results in the unequal distribution of power and privilege based on skin color. Whiteness produces normative privileges granted to white-skinned individuals and groups, yet is often invisible to those who benefit from it. Whiteness is normalized and operates as the standard. See for example Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010). Legal scholar Cheryl I. Harris details the evolution of whiteness in the US into a form of property enshrined and protected by law, in stark opposition to enslavement; Cheryl I. Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (1993). Cultural theorist and activist Dylan Rodríguez writes of white supremacy as a “historically dynamic logic of social organization,” observing that, “The foundational orderings of white supremacy form multiple global circuits of trauma, fatality, and social disruption, each of which is central to—in fact historically determinant of—the present-tense social forms under which we live”. Dylan Rodríguez, “White Supremacy as Substructure: Toward a Genealogy of a Racial Animus, from ‘Reconstruction’ to ‘Pacification’ “, in State of White Supremacy: Racism, Governance, and the United States, ed. Moon-Kie Jung, João H. Costa Vargas, and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011). See also Charles W. Mills, “White Supremacy as Sociopolitical System: A Philosophical Perspective,” in White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism, ed. Ashley ‘‘Woody” Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (London and New York: Routledge, 2003).

[6] Sonja Dahl, “Whitework,” in Discursive (Eugene, Oregon: Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 2018), 48.

[7] Sonja Dahl, interview by L Vinebaum, October 2018.

[8] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[9] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[10] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[11] Janet Mawhinney, “Giving up the Ghost: Disrupting the (Re)Production of White Privilege in Anti-Racist Pedagogy and Organizational Change” (MA Thesis, University of Toronto, 1998).

[12] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[13] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[14] Sonja Dahl, interview by L Vinebaum, August 2023.

[15] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[16] Dahl, 2018, n.p.

[17] Dahl, 2018, n.p.

[18] Whitework styles (many of which are named after the regions in which they developed) include broderie de Marseille or Marseilles quilting, Chikankari, broderie Anglaise (which originated not in England but in Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia), Hardanger embroidery, Frisian whitework embroidery, Hedebo embroidery, Dresden work, Mountmellick embroidery, reticella, Sardinian knotted embroidery, Richelieu cutwork, Madeira embroidery, Schwalm, Hardanger, Helm, Appenzell, and Ayrshire lace. See in particular Jean Taylor Federico, “White Work Classification System”, Uncoverings 1 (1980); Judith Reiter Weissman and Wendy Lavitt, Labors of Love: America’s Textiles and Needlework, 1650-1930 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987); and Whitework Embroidery: the Merging of Needle, Thread, Cloth and Spirit (Berkeley CA: Lacis Museum of Lace & Textiles, 2006). Chikankari and broderie de Marseille are also done with colors.

[19] Viveka Hansen, “19th century Whitework Embroidery”, iTEXTILIS Historical Reproductions XXXVI, July 14, 2015.

[20] Laila Tyabji, “Handcrafting a culture,” 2007, https://www.india-seminar.com/2007/575/575_laila_tyabji.htm.

[21] Weissman and Lavitt, 1987.

[22] Kathryn Berenson, Quilts of Provence: The Art and Craft of French Quiltmaking (New York: Potter Craft, 2007).

[23] Jacqueline M. Atkins, “From Lap to Loom: The Transition of Marseilles White Work from Hand to Machine,” The Chronicle 54 no.1 (March 2001). Berenson (2007) notes that the French textile industry also profited greatly from copying Indian printed textiles.

[24] Dr. Jess Bailey and Dr. Sharbreon Plummer, Why Learn Quilt History? The People’s Quilting Bee, Zoom lecture, September 6th, 2023.

[25] Berenson, 2007, 50.

[26] Weissman and Lavitt, 1987.

[27] Elizabeth Donaghy Garrett, At Home: The American Family 1750-1870 (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1990), 166.

[28] Garrett, 1990.

[29] Ana Araujo, “Repetition, Pattern, and the Domestic: Notes on the Relationship between Pattern and Home-making,” Textile 8, no.2 (2010), 186. While not explicitly stated, she is writing about white Victorian women. Araujo observes that the Western impulse to relegate women to the domestic sphere originated in ancient Athenian society, to allow male traders to wrest control of the lucrative textile trades away from women traders and entrepreneurs.

[30] Stacy C. Hollander, “White on White (and a little gray),” Folk Art (Spring/Summer 2006), 33.

[31] Painter, 2010. Ironically, neoclassicism’s nostalgia for the color white was founded on a serious misconception: ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and architecture were often colorful, not white. Mark Abbe, an archeologist and a foremost scholar of color in ancient Greek and Roman art, observes that many sculptures were originally painted in color, but over time the paint would peel off. Some works were not properly preserved; many were over-cleaned and stripped of their colors to uphold the color white as an aesthetic ideal, even as scholars knew otherwise. Mark Abbe, “Politura and Polychromy on Ancient Marble Sculpture,” CLARA 5 no.1 (2020), 12. See also Margaret Talbot, “The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture, “The New Yorker, October 22, 2018.

[32] See for example Immanuel Kant, “Von der verschiedenen Rassen der Menschen” (“On the Different Races of Man”), 1777, translated by Jon Mark Mikkelsen, in Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze ed., Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 1997); Charles Davis, Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019); and Patrick Brantlinger, “A Postindustrial Prelude to Postcolonialism: John Ruskin, William Morris, and Gandhism,” Critical Inquiry 22, no.3 (Spring 1996).

[33] Painter, 2010. See also kihana miraya ross, “Opinion: Call It What It Is: Anti-Blackness”, The New York Times, June 4, 2020.

[34] Dahl, interview, 2018.

[35] In addition to being settler on American lands, Dahl’s Dutch ancestors were involved in the colonization of Indonesia; notably her great-great uncle was Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 1940-1945, when the Indonesian National Revolution began. He was a staunch defender of Dutch colonization of Indonesia who vehemently opposed Indonesian independence.

[36] Rachel Flowers, “Refusal to forgive: Indigenous women’s love and rage”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 4, no.2 (2015), 33-34.

[37] Flowers, 2015.

[38] Other patterns and designs typical of Oregon Trail quilts include “wagon wheels” and “wandering foot”, which symbolize the turning of wheels across territory, wanderlust and a desire to explore and settle the nation. Leaves and flowers symbolize love, renewal, healing, strength, and abundance, while celebratory patterns like the “wedding dress,” “steps to the altar,” and “tree of life” marked milestones like marriage and childbirth; see Mary Bywater Cross, Quilts of the Oregon Trail (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd, 2007).

[39] Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 21, 2006), 388.

[40] J. Kehaulani Kauanui, “‘A Structure, Not an Event’: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” Lateral 5, no. 1 (May 2016), n.p.

[41] In Dennis, 2014, 282.

[42] On boarding schools see in particular K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, Teresa L. McCarty, eds. Native American Boarding School Stories, special issue of the Journal of American Indian Education 57, no. 1 (Spring 2018); and David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875–1928, Second Edition (Lawrence KS: University Press of Kansas, 2020). See also the online resources that accompany the exhibition Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories at the Heard Museum, https://boardingschool.heard.org/.

[43] Indigenous quilter Susan Hudson, “Honoring Our Ancestors”, The People’s Quilting Bee, Zoom lecture, November 8th, 2023.

[44] Susan Hudson discusses her work in the 2019 episode “Quilts” in the PBS series Craft in America; and in The People’s Quilting Bee, 2023.

[45] https://www.pendleton-usa.com/content-our-mills.html

[46] Because Pendleton is privately owned, financial data is hard to come by. Pendleton’s annual revenues for 2022 are estimated at $190 million, see https://www.zippia.com/pendleton-woolen-mills-careers-34545/revenue/. The company’s revenues have been estimated as high as $230 million and $267 million, but these figures are impossible to verify; see https://rocketreach.co/pendleton-woolen-mills-profile_b5c6663ff42e0c91 and https://www.zoominfo.com/c/pendleton-woolen-mills/88228144.

[47] Matthew Dennis, “Natives and Pioneers: Death and the Settling and Unsettling of Oregon,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 115, no. 3 (Fall 2014), 282.

[48] David G. Lewis, “Four Deaths: The Near Destruction of Western Oregon Tribes and Native Lifeways, Removal to the Reservation, and Erasure from History,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 115, no. 3 (Fall 2014), 416.

[49] Stacey L. Smith, “Oregon’s Civil War: The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 115, no. 2 (Summer 2014).

[50] Walidah Imarisha, “How Oregon’s Racist History Can Sharpen Our Sense of Justice Right Now,” Portland Monthly, March 2020. Imarisha continues, “when I think of this history, it’s not the forces of oppression I center. Instead, I focus on the radical visioning of communities of color who were able to dream themselves into futures barred to them.” n.p.

[51] Dahl, interview, 2023.

[52] See Bakkom, Gail,” ‘Candlewicks’: white embroidered counterpanes in America 1790-1880,” Uncoverings 16 (1995). The technique is confirmed by information contained in the quilt’s register held by the Lane County History Museum, email correspondence with Robin Myers, Curator of Collections, September 2023.

[53] See https://embroideryonline.com/history-of-candlewicking/, https://www.needlepointers.com/main/showarticles.aspx?navid=3927, and https://www.ehow.co.uk/facts_6944219_history-candlewicking.html. I have not been able to corroborate this information in scholarly texts.

[54] Cross, 2007.

[55] Cross, 2007.

[56] Matthew Dennis, “Natives and Pioneers: Death and the Settling and Unsettling of Oregon,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 115, no. 3 (Fall 2014), 290.

[57] Tom Vincent, ” ‘Evidence of Womans [sic] Loyalty, Perseverance, and Fidelity’ “: Confederate Soldiers’ Monuments in North Carolina, 1865-1914,” The North Carolina Historical Review 83, no. 1 (January 2006), 68.

[58] Vincent 2006; see also William A. Strasser, Jr., ” ‘Our Women Played Well Their Parts’: Confederate Women in Civil War East Tennessee”, Tennessee Historical Quarterly 59, no. 2 (Summer 2000).

[59] Two examples of Confederate quilts containing photographs of Confederate generals can be viewed at https://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2021/05/cdvs-quilts-1.html

[60] The quilt is discussed in Vincent (2006) as an example of women’s fundraising and organizing efforts. The quilt can be seen on Historian Barbara Brackman’s Civil War Quilts blog, http://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2014/07/maria-spears-quilt-fundraiser-for.html.

[61] Ben Bruce, The Rise and Fall of The Ku Klux Klan in Oregon During the 1920s, Voces Novae 11, Article 2 (2019), 23.

[62] Kloran or Ritual of The Women of the Ku Klux Klan (Little Rock: Women of the Ku Klux Klan, 1928), 43.

[63] Kathleen M. Blee, “Women in the 1920s’ Ku Klux Klan Movement”, Feminist Studies 17, no. 1 (Spring, 1991).

[64] Blee, 1991, 60.

[65] Marsha MacDowell, Charlotte Quinney, and Mary Worrall, “The KKK Fundraising Quilt of Chicora, Michigan,” Uncoverings 27 (2006).

[66] Katherine Lennard, “The Running Stitch,” Journal of American Studies 52, no. 4 (2018).

[67] Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners (Little Rock: Women of the Ku Klux Klan, 1928) [pamphlet].

[68] A scanned image of the note together with supplementary information about the quilt was generously provided by Michael Siebol, Chief Curator of Collections and Archives at the Yakima Valley Museum, September 2023 [email correspondence].

[69] Lennard, 2018, 907.

[70] The daughter shared this information in a phone call to the Yakima Valley Museum’s director. Supplementary information provided in email correspondence with Michael Siebol, September 2023.

[71] MSU Museum collection records.

[72] MacDowell, Quinney and Worrall, 2006.

[73] Craig Fox, Everyday Klansfolk: White Protestant Life and the KKK in 1920s Michigan (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011).

[74] https://www.splcenter.org/hate-map?state=MI

[75] As detailed in Elizabeth Gillespie McRae, Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[76] For more details see MacKenzie Ryan, ” ‘Better martyrs’: the growing role of women in the far-right movement”, The Guardian, August 12, 2023.

[77] Southern Poverty Law Center, The Year in Hate & Extremism 2022, 2023. The report draws parallels to white supremacist parent groups that tried to re-segregate public schools during the civil rights movement.

[78] Dahl, interview, 2023.

[79] Dahl, interview, 2023.

[80] Exhibition statement.

[81] Louis Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, translated by Ben Brewster (New York, London: Monthly Review Press, 1971), 158.

[82] Stuart Hall, “Signification, Representation, Ideology: Althusser and the Post-Structuralist Debates,” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 2, no. 2 (June 1985).

[83] Althusser 1971, 162.

[84] Hall, 1985.

[85] Hall, 1985, 112 [italics added].

[86] See for example, W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, “Back Toward Slavery” in W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward A History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America 1860-1880, First Edition (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935), in which he details the political and violent overthrow of Reconstruction; and Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The First White President”, The Atlantic, October 2017. See also Rory McVeigh and Kevin Estep, The Politics of Losing: Trump, the Klan, and the Mainstreaming of Resentment (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), which draws parallels between the rise of the KKK in the 1920s, and the resurgence of white grievance as harnessed by Donald Trump.

[87] Kehinde Andrews, “The Psychosis of Whiteness: The Celluloid Hallucinations of Amazing Grace and Belle“, Journal of Black Studies 47, no. 5 (2016), 436.

[88] Andrews, 2016.

[89] The psychosis of whiteness, a talk by Kehinde Andrews at the London School of Economics, October 25, 2023.

[90] Andrews, 2016.

[91] The psychosis of whiteness, 2023.

[92] Dahl 2018, n.p.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.