Plots in Gardens

In 2015, an immense shopping mall opened in Greater Noida, India. The name is unexpected: “The Grand Venice Mall.” It is described on its website as “an opulent Venetian-themed mall” which includes a zipline, a “Horror House,” and a 7D cinema. The entertainment complex is located in a region severely afflicted by water shortages: in 2013, only fourteen inches of rain fell, and faucet water (when available) has a yellowish color, polluted by pesticides and other industrial residues.[1] Thus, the peculiar specialty of the GVM is somewhat counterintuitive: lavish water displays. Aside from various fountains, in accordance with its Venetian theme, the Mall contains a gondola basin where visitors can be ferried around for an “authentic” Venetian experience. According to anthropologist Kate Weston, thirst, politics, and profit do not exhaust the reasons why people make use of water, and “much less what entices them into unsustainable uses.”[2] Weston argues that play and playfulness are also reasons why people make use of water: in in the case of the GVM, such playfulness acquires the shape of what Mikhail Bakhtin would call the “carnivalesque”: a farce that turns society and its values upside down, where everything becomes the opposite of what it normally is. Just like in medieval Carnival celebrations servants would become masters and even priests would utter obscenities in church[3], so the Grand Venice Mall makes a playful spectacle of an arguably immoral wastage of water. Rather than being simply accessory, or a medium through which other elements are showcased (like in an aquarium, for example), at the Mall water becomes “a spectacle in its own right”[4], and a veritable tourist attraction, there for no other reason than to be admired.

It is not only where water is scarce that it exerts such fascination. The construction of surprising and ingenious fountains—not designed for drinking or for the distribution of water, but for pleasure—has characterized the most disparate cultures and historical periods. This was especially the case in Europe, where since the 16th century the fashion of gardens and water games spread among wealthy and noble families, who invested immense resources in the construction of elaborate gardens with water displays. These gardens were not exclusively decorative in their function: they were places where the encounter of artifice and nature was celebrated, and where intricate symbolism and allegorical plots—sometimes describing a path of enlightenment, or a transition from darkness to light—unfolded in visual and sensorial itineraries which are often invisible to the contemporary visitor. While the content of such allegorical, alchemical, and mythological pathways was erudite and often complex, the garden was a place of relaxation and wonder, and symbolic contents could be represented with a variety of surprising devices. In Italy, two such gardens make use of water as a plot device for building symbolic narratives.

The 16th century was the age of Mannerism, an aesthetic style characterized by a strong interest in the artificial and its tension with the natural. In this period, Italy witnessed the construction of several highly elaborate gardens, a fashion that then spread throughout Europe. As explained by scholar Antonio Pinelli, gardens were the ideal settings to develop and elaborate some of the concerns at the core of the Mannerism:

[T]he mannerist garden, with its geometric hedges and wild gorges, crossed by labyrinths and water games, peopled by automata and giants, with its cosmological allusions mixed to moralising precepts or to playfulness, is one of the privileged sites where the eternal competition…of art and nature takes place.[5]

The most well-known of such gardens, and one that captivated the imagination of generations of visitors and artists, is that of Villa D’Este in Tivoli (Rome), still accessible today. If the name “Tivoli” rings familiar, it may be because the historical Tivoli amusement park in Copenhagen takes its name from this location, an evidence of the extent to which the park of Villa D’Este has become synonymous with enjoyment and wonder. Popular also in Romantic times, when legendary pianist Franz Liszt sojourned there in several occasions, Villa D’Este is now a UNESCO heritage site. In its gardens, water is the means through which various plots are narrated and tied together: its flow is regulated to produce a variety of effects, conferring dynamism and meaning in displays that have become known aptly as Teatri delle Acque (water theaters).

In the imposing Fontana dell’Organo (Organ Fountain) or Fontana del Diluvio (Fountain of the Deluge), for example, water was deployed in its various states to symbolically narrate the emergence of water from the entrails of Nature. Through a system of pipes and mechanisms activated solely by the flow of water, two trumpets held by statues would be made to play. Then, a water-organ would play a piece of music. While a newly-built and more resistant organ is still visible and audible today, in the original setup, the organ stood on an artificial cliff behind the curious statue of earth goddess Diana Ephesia, represented with many breasts (these breasts are, actually, bull testicles, but this is another story). The statue has been moved to another location in the garden, but can still be seen there.

Fountain of Diana of Ephesus (image via Wikimedia)

At the end of the music, the diluvio would begin: water would suddenly gush through fixtures on the façade of the fountain, and simultaneously be made to spray vertically from below. As described by Barisi, in some hours of the day, rainbows would be formed on the nebulized water, which may have added further realism to the end of the tempest. Then, concluding the spectacle, a triton would play a trumpet.[6] With this fountain begins a symbolic plot describing the eternal cycle of water emerging from the earth (as symbolized by the statue of goddess Diana), wandering through the underground tunnels (some artificial grottos), and then flowing into the Ocean in the marvellous fountain of Neptune, whose water spouts are several meters high, and into peaceful basins full of fish.

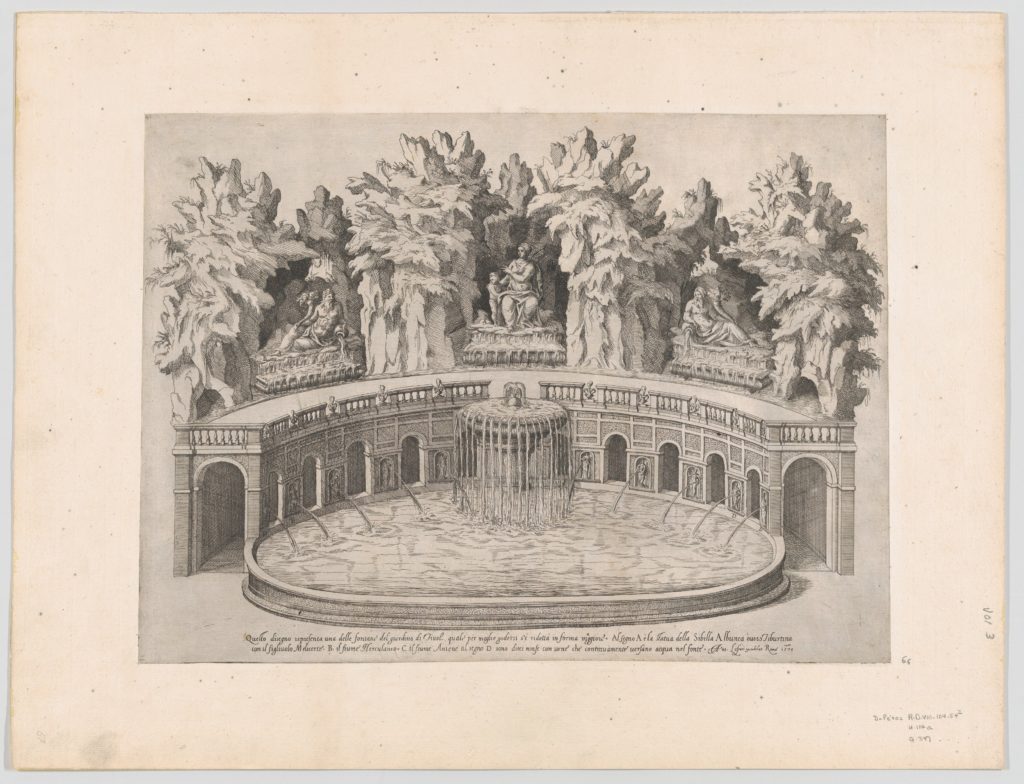

In another area of the garden, the flow of the river Aniene from Tivoli to Rome is narrated and recreated in miniature. In a first fountain (the Fontana dell’Ovato), the great waterfall of the river in Tivoli is evoked, just below the statue of the Sibyl, mythological prophetess of Tivoli. If from this historical image the fountain looks rather tame and orderly, let me assure you that the waterfall produces a very loud sound, and the central statue of the Sibyl, now surrounded by vegetation, has the appearance of an ancient and somewhat threatening goddess.

Etienne DuPérac, Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: Fountain and Gardens of the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, 1575.

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The plot then continues with a famous terrace (the Viale delle Cento Fontane) whose nearly three hundred fountains represent the aqueducts and water courses between Tivoli and Rome. The narrative arc culminates in the Fountain of Rometta (Little Rome), as the water enters a miniature Rome: although today the fountain looks different from how it was initially conceived, in the past, miniatures of all the seven hills of Rome would have been there, each with its own characteristic monuments.[7] As you can see from this image (), visitors seem to have been able to access Little Rome, breaking the divide between observers and display (a characteristic concern of Mannerist aesthetics).

The garden of the Villa was planned by architect Pirro Ligorio (c.1510 -1583) for Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572), son of the more famous Lucrezia Borgia and a renowned lover of the arts. The effort put into the creation of the garden was immense, demonstrating its importance as something more than mere extravagance. The rocky and uneven ground, with a difference in height of forty-five meters, needed to be leveled; inhabitants who owned properties in the area had to be evicted (leading to the cardinal being sued twelve times in 1568)[8], and an underground canal of two hundred meters was created to deviate the Aniene river and provide the garden with a continuous water supply. According to the guide, the villa and its gardens were designed to embody and convey an “iconological programme” aimed at celebrating the cardinal, his virtues, and his family. Indeed, the D’Este were one of the most powerful families in Italy, and Ippolito had been made Archbishop of Milan at only ten years of age. For years he schemed in the hope of becoming Pope, but failing in his objective withdrew to live in Tivoli. The legacy of his noble family was celebrated in the architecture of the garden: the Viale delle Cento Fontane, for example, is decorated with fleur-de-lis and eagles, which are present on the family crest. The eagle can also be seen on top of Fountain of the Owl, capable of producing the sound of birds, and of that of the Deluge. At the same time, both the villa and its gardens are replete with evocations to the figure of Hercules, which the D’Este considered to be their mythological ancestor. Thus, quoting Barisi,

All the elements of the architectonic composition, from the many fountains to the water courses and water games, from the layout of the vegetation to the pictorial decoration of the interiors, to the […] ancient statues, had to contribute in unitary fashion to the development of symbolical, allegorical, and celebrative themes.[9]

While many other gardens from this period are also famous and attract many visitors, what makes Villa D’Este so special is the extent to which the aquatic spectacle is deployed to enliven scenes, further a plot, or simply be admired. Some of the jeaux d’eau are unfortunately no longer visible today. The war-themed Fountain of the Dragons, for example, still exists, but it is no longer able to produce the sound of explosions or simulate a rainstorm.

As you will have noticed by now, the Mannerist garden was characterized by a strong theatrical element: indeed, the spread of theater shows contributed to the adoption of theatrical features (labyrinths, trap doors, surprise apparitions) in the aesthetic repertoire of parks and villas[10], and many garden architects were also stage designers. The same is true for a garden built a few centuries later, the 19th century Parco di Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini (Genova), which in 2017 won a prize as the most beautiful garden in Italy. The park architect, Michele Canzio, was the scenic designer of the Carlo Felice theater in Genova. Just like a theater play, the garden is subdivided in three acts (The Return to Nature, the Return to History, and Catharsis) and twelve scenes.

The garden’s creator, Ignazio Alessandro Pallavicini, was knowledgeable in esoteric matters and Masonic symbolism. The latter draws on a varied body of Neoplatonic, alchemical, and hermetic traditions—heterogeneous bodies of knowledge which could be said to have in common a conception of the cosmos as being similar to a graduated scale that begins in chaos and darkness and culminates in enlightenment and divinity. In Masonic and alchemical conceptions, the knowledge-hungry seekers or questers, in their pursuit for true knowledge, may ascend along this upward path from a condition of darkness of confusion to one of wisdom. Accordingly, the garden is designed as a path of ascension from darkness to light—a journey which takes about two hours to complete. Like the zeitgeist of its time, it is also imbued with Romantic aesthetics and sensitivities.

In this garden too the vegetation, the shape of water courses, and sudden views are carefully deployed to convey allegorical meanings. A particularly spectacular story arc is that of the third act, describing a cathartic journey to Paradise. In line with Masonic conceptions in which a higher state of knowledge and enlightenment can be achieved only by confronting death, the visitor is made to cross dark and suffocating grottos. In hermetic alchemical traditions, those who wish to gain real knowledge must go through a spiritual condition of darkness (called nigredo or putrefaction in alchemy), a state filled at once with chaos and potentiality. In alchemical imagery, this stage is often represented as a sarcophagus: a symbol of death, certainly, but also of transformation. Thus, the seekers must overcome this condition and confront their own fears in order to be able to emerge from it transformed and ascend to enlightenment. For the visitor, the effect is quite striking: no sounds or bright light from the outside can reach us in the grottos, and the impression is that of briefly losing contact with reality in the blackness of the tunnel. Then, all of a sudden, an explosion of light opens up before us as a vision of a bright and peaceful lake with a white templet in the middle. After the disorienting experience of crossing the grotto, this sudden and completely unexpected view really gives the feeling of having reached an earthly paradise.

Temple of Diana in the Villa Durazzo Pallavicini (image via Wikimedia)

Water has a very important narrative function here: the cave-like tunnels could in the past be crossed by boat. This immediately evokes the mythological figure of Caronte (Charon), the ferryman on the River Styx, strengthening the association between the grottos and hell. Moreover, the crossing of a body of water has always been associated, in mythology, with the passage from one world to another (from that of the living to that of the dead, for example). If in other scenes water flows rapidly, or plunges into a basin at the bottom of a gorge to symbolize the sublime and terrifying power of nature, in this scene the water is a placid surface onto which the temple and the garden area are mirrored.

Spectacular scenic effects with allegorical meanings are many. A bright terrace with a neoclassical portal inviting the visitors to leave their cares behind them is completely transformed, in crossing the arch, into an alpine hut surrounded by thick vegetation. The visitor is thus almost physically transported to another dimension, foreign to that of everyday existence. Similarly, from an area of the garden dedicated to history and war, one can see a ruin on a distant hill, which in the plot of the garden’s creator is imagined as belonging to a rival faction, destroyed as a result of combat. This too is a scenic device, as the ruin was nothing more than a local building, remodeled to look war-damaged in order to illustrate the destructiveness of all conflict.

Interestingly, the garden does not end with the conclusion of the esoteric narrative arc. After the third act, a last section called “Exodus” is dedicated to water games. According to the explanatory placard, this section recalls the moment of exodus in Greek tragedy, and offers the visitor a moment of total enjoyment “to allow profound reflections to sediment in the pleasant sound of laughter.” While the water games are today not always active, in the past the visitors would reach a little gazebo, where they would be sprayed by water. In running away, they would be forced to enter a labyrinth, in whose seating area further water games would be activated.

This section of the garden dedicated to pure enjoyment leads us back to Weston’s analysis. Weston’s remarks about the Grand Venice Mall make us reflect on play and playfulness, key elements of culture that are almost always excluded in analyses of social life. As discussed, scenic gardens have been places through which important families could display their erudition and availability of economic resources—where the owner of the garden could feel like the god and creator of a microcosm, and where Artifice could at times triumph over Nature by manipulating and imitating it. But philosophical, political, and economic factors do not exhaust the reasons why such gardens were built: amusement, surprise, marvel, and the delight of the senses were also of crucial importance. Thus, while the cultural and political conditions that led to the emergence of these gardens no longer exist, and their allegorical itineraries are not easily relatable in the present day, the gardens’ capacity to elicit wonder, surprise, and pleasure remain.

[1] Kath Weston, Animate Planet: Making Visceral Sense of Living in a High-Tech Ecologically Damaged World (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 136.

[2] Weston, 136.

[3] The latter is described by Jung in “Four Archetypes”

[4] Weston, 163

[5] Antonio Pinelli, La Bella Maniera (Torino: Einaudi, 2003), 153.

[6] Isabella Barisi, Guida a Villa D’Este (Rome: De Luca Editori D’Arte, 2004), 66.

[7] Barisi, 88.

[8] Barisi, 11.

[9] Barisi, 13.

[10] Pinelli, 152.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.