On Holi-delay

Department of Art, University of Reading

This unpublished paper was originally written in 2013. This paper has been updated with additional survey results and an Addendum.

Abstract

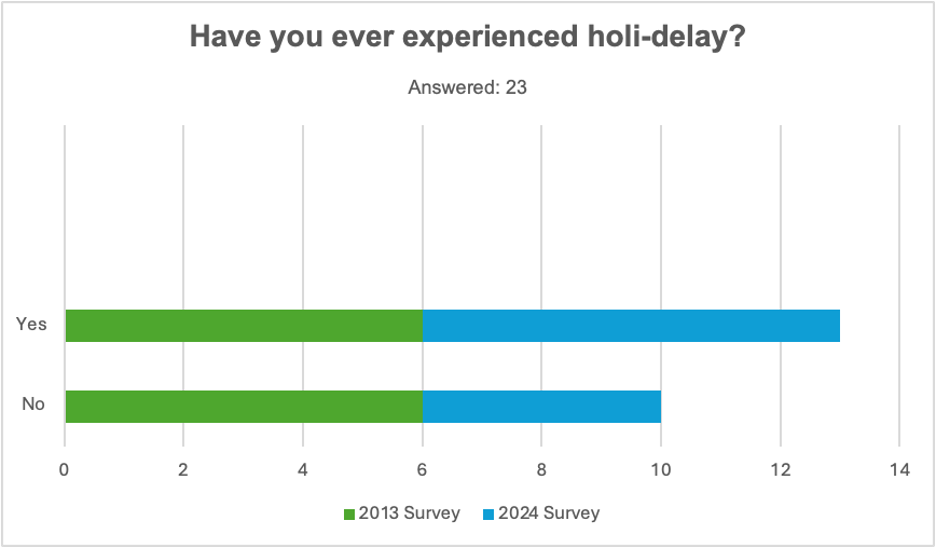

Although 46% of people have experienced holi-delay, this condition has remained overlooked and underreported. [Figure 1] Holi-delay is a condition where people only get excited about holidays after they happen, and this condition is distinct from, but related to, holidelay, holiday apathy, and holiday blues. Qualitative and quantitative data was collected through a primary case study, as well as a survey conducted in 2013 and 2024 with participants from Canada, Italy, Nigeria, Sweden, the UK, and the US. This paper details the key markers of holi-delay, focusing on the holiday preparation phase. Holi-delay’s most authoritative literature is located in blogs, social media comments, and casual conversation, and I draw on these pathmaking sources for analysis. In particular, I use Dowshen’s (2010) four phases of “Getting in the Holiday Spirit” to structure a comparison of normative holiday behavior with the behaviors of people who experience holi-delay within a broader discussion of the key markers of holiday, which include: a desire to experience holidays (Mitchell 2005), a lack of confidence in setting appropriate expectations which creates a barrier to higher-order brain mechanisms (Ariely, 2009), a preference for expectant emotions (Bloch 1995), the weighing of internal cues more strongly than external cues (Gregoire, 2013), and a preference for spontaneous communitas (Turner, 1982), with markers of introversion (Ghose, 2013) and individualism (Nelson, 2013). Holi-delay is an important lens through which to better understand the shift in the emotional-temporal landscape of communal celebrations. Combined with proper use of our inconvenience drive (berlant, 2022), it offers an alternative approach to holidays that invites a diverse array of experiences that enable authentic interactions and deconstruct social hierarchies.

Introduction

In this paper I will argue for the existence of holi-delay, a widespread condition that up until now has gone under-examined although 46% of the population have reported experiencing it. [Figure 1] Holi-delay is a condition where people only get excited about holidays after they happen. Holi-delay was coined as a term during a casual conversation in 2005 at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio (US), and the key markers of holi-delay include: a desire to experience holidays, a lack of confidence in setting appropriate expectations which creates a barrier to higher-order brain mechanisms, the weighing of internal cues more strongly than external cues, and a preference for spontaneous communitas with markers of introversion and individualism.

While holi-delay shares several underlying causes as holidelay, holiday blues and holiday apathy, its emotional-temporal trajectory is markedly different and warrants a separate diagnosis. xtremerange (2012) defines holidelay as when business decisions are delayed close to the holiday season; Felson, Fraser and Watson (2024) detail the symptoms of the holiday blues which include feeling lonely, sad, and angry, sleeping poorly, and having headaches, tension and fatigue; and Fontyn (2017) notes that holiday apathy is caused by repeated anti-climactic experiences that leave the holiday experiencer stressed and irritated with the fact they didn’t experience the contentment they expected. Whereas those who experience the holiday blues and holiday apathy maintain a negative outlook on the holiday before, during, and after its celebration (and often blame the holiday itself), those who experience holi-delay can (and mostly do) generate positive feelings toward the holiday. So why can’t those who experience holi-delay rally their emotions in time to take advantage of the social moment? Is their social anxiety getting the better of them? Are the anti-consumerist habits they learned from their hippie parents landing them in the middle of a holiday without the proper social leanings and hype generating material implements?

It is important to examine holi-delay as a widespread condition, better understand the circumstances within which it arises, and gather resources to further study it and its possibilities. If left unexamined, holi-delay threatens to tear our social order apart. This paper will conclude with a call to action, hypothesizing about the possibilities of understanding holi-delay as a reflection of a growing shift in how communities form and celebrate, and therefore a useful lens through which to explore what alternative forms of communal celebration could look like.

Method

Method

This study was largely guided by close observation of one primary case study: me. Additionally, a survey was conducted in 2013 and 2024, the details of which follow below.

Participants

The research participants for both the 2013 and 2024 survey were recruited through both program and personal affiliation. In the 2013 survey, the majority of survey participants took Shannon Stratton’s 2013 course Party as Form alongside me at Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists Residency in Saugatuck, Michigan (US). To increase the number of survey participants I also reached out to my larger social network. Thirteen Millennials from the US took the 2013 survey.

In the 2024 survey, the research participants were also invited to share the survey themselves, so in addition to participants recruited through my academic and personal affiliations, participants also represented a wider network. The 2024 survey participant recruitment was 37% from program affiliation (PRAKSIS’s Party as Form 2024 Residency), 27% from personal affiliation, and 36% from a wider network. Eleven Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z from Canada, Italy, Nigeria, Sweden, the US, and the UK took the 2024 survey.

Materials

Answers to the survey questions were collected via SurveyMonkey (2013) and Google Forms (2024). The participant’s name and email were collected, and they were asked to answer the following questions:

- Have you ever experienced Holi-delay?

- Do you look forward to celebrating holidays?

- Do you have a favorite holiday? If so, what?

- Please share a holiday memory

- Are you an Introvert or Extrovert?

- Do you experience FOMO (Fear or Missing Out)?

- How’s your social timing (Ex. Are you right there with the joke or completely clueless, etc.)

- Which Generation are you?

- Do you prefer Coke or Pepsi?

Procedure

Research participants did not sign a consent form and therefore when their information was used it was anonymized. Each survey participant was emailed or texted a link to the survey and took the survey online in private. Along with the participant’s name and contact information, the only required question was, “Have you ever experienced Holi-delay?”

Results

In his blog post at 5:06 p.m. Adamhuet (2011) reflects on “What If There Were No Holidays?”, writing:

This would such a sad thing to have happen…. We use the holidays as an excuse for many things… Even though I keep calling the holidays an excuse I don’t want it to sound like a bad connotation. It’s just the way it is but what if we didn’t have this time to relax and reconnect? I can’t think of a good reason why we would want to get rid of this time of year…Not having this day would hurt us in the regard that this is what some people use to keep themselves going. They see it as an escape from the day to day routine that they normally fall into and want to get out of.

Here Adamhuet (2011) demonstrates the position of the unimaginative realist because although he recognizes the negative aspects of holidays, he advocates for holidays to continue to exist simply because of the status quo.

From the findings of this study it is clear that holi-delay’s emotional-temporal landscape presents an alternative approach to holidays. If more people are finding it more fulfilling to opt out of holidays, lean into their internal cues and individual wants, and choose their own adventure, how can we enable these authentic interactions? If left unacknowledged, holi-delay can become a chronic condition affecting one’s social timing and ability to commune with others which can have long-lasting effects on one’s ability to find community and participate in society. But embracing holi-delay as a condition, rather than ignoring it, could be an opportunity for a radical intervention in how we commune. Increased cultural awareness of the condition could also serve as an invitation to those who do not experience holi-delay to reexamine the events, behaviors, traditions, objects, and opportunities that hold us together.

Discussion

This paper first discusses what holidays want from us and then contrasts the holi-delay experiencer’s emotional navigation through the normative experiences of a holiday, focusing on the preparation phase preceding the holiday. This is followed by a discussion of the potential underlying causes of holi-delay and how recognizing holi-delay as a widespread condition provides an opportunity to recalibrate communal celebrations.

Standard Holiday Protocol

Instead of being a time of unusual behavior, Christmas is perhaps the only time in the year when people can obey their natural impulses and express their true sentiments without feeling self-conscious and, perhaps, foolish. Christmas, in short, is about the only chance a man has to be himself.

—Francis C. Farley

Mitchell’s (2005) proposition “What do pictures want?”, prompts me to begin this discussion about holi-delay by asking, “What do holidays want?” Mitchell (2005) uses a still from David Cronenberg’s Videodrome to illustrate, “the picture-beholder relationship as a field of mutual desire.” [Figure 2] In this still we see Videodrome’s protagonist Max Renn pushing his head into a television screen that swells out towards him. Similar to the picture-holder relationship, the holiday-participant relationship is also “a field of mutual desire.” We construct holidays as an opportunity to act on our desires and experience leisure and chaos in a way that doesn’t dismantle our social order, without which we would be left socially stranded and physically uncomfortable at best, and criminalized at worst.

Holidays’ continued existence requires that we recognize and prioritize them as an important part of a functioning society through becoming “holiday stewards,” a significant body of active participants that manifest the holiday and its spirit. These holiday stewards actively plan celebrations: they care enough to book the concert hall ahead of time, send out the invitations, herd the children, order streamers that match, and make sure the pie doesn’t have peanuts in it because three people in attendance have nut allergies.

However, for many people holidays are marked only through passive observation. For example, many people “observe” Labor Day merely because they get off work rather than attending a protest to fight for the rights of workers. Observation alone does not guarantee the existence of a holiday, nor does it make one feel as if one is fully participating in or adequately “celebrating” the holiday. One survey participant made a point to distinguish between the holidays they observed and the holidays they celebrated. They described Mother’s Day as a holiday they observed (rather than celebrated) because, “it’s not like I called my mother the night before, had a day out with only the two of us, got trashed together, or bought her a cake that said MOTHER on it.” By describing a Mother’s day that mimicked their behavior on holidays that they “celebrated” (such as their birthday, their partner’s birthday or New Years), this survey participant inadvertently highlighted the greater value we place on holidays that we “celebrate” because of the higher level of our participation.

The standard trajectory of every holiday (religious or secular) includes three phases. The initial phase generates excitement (gets participants in the “holiday spirit”), and it includes important preparatory activities such as buying stuff to build a supportive sonic, physical, and social environment or engaging in nostalgia-triggering activities like family traditions (i.e., hanging particular decorations that remind you of family members or vacations, gathering together to listen to 98 Degrees’s seminal 1998 album This Christmas, etc.). The second phase is the holiday itself, and this includes carrying out the plans you had laid out beforehand, joining in, and feeling a sense of fulfillment in real time. The third and final phase is the moment of reintegration into your everyday life. This final phase includes a reflection on the holiday’s events; a release of the desire for the meeting of those specific feelings, activities, environments, objects, smells, foods until the next year; and a positive anticipatory look to the next thing (perhaps even the next holiday).

These three phases of every holiday parallel the three phases van Gennep (1977) distinguishes in a rite of passage: separation, transition, and incorporation. Like the transition phase in rites of passage, a holiday acts as a liminal phase that allows for subversive behavior, although this behavior ultimately is used to support the status quo. Turner (1982) explains that this liminal phase also introduces the understanding that chaos is the alternative to cosmos (i.e. structure), and so although it is necessary to have moments of chaos, it’s best to stick with the cosmos.

Standard holiday protocol at its core supports a holiday’s continued existence through propagating the belief that participating in the holiday gives us the opportunity to act on our desires within the appropriate time slot.

Normative Holiday Behavior vs. holi-delay

Preparation is the initial phase of every holiday and the primary means through which people actively participate in holiday celebrations. Dowshen (2010) highlights preparation as an important part of holidays because this phase is about more than planning. It is about getting in “the holiday spirit” and opening ourselves up to the joy that’s possible through the creation of that joy through our actions. Preparation allows us to generate excitement about the holiday by outlining a set of expectations that we can fulfill before and during the day of the celebration. By following through on set expectations, we are able to feel a sense of fulfillment. This sense of fulfillment is the goal of the celebration day itself and also eases the third and final post-holiday digestion phase.

Dowshen (2010) demonstrates that these three phases (preparation, holiday, reintegration) are also contained within the preparatory phase itself. He structures his argument in four sections that build on each other: “Anticipate Your Holiday Mood…,” “… Then Make It Happen!,” “So How Does It Feel?”, and “Make Your Mood Contagious.” I will discuss holi-delay using Dowhen’s subcategories, first in terms of normative holiday behavior and then in terms of someone experiencing holi-delay.

Anticipate Your Holiday Mood….: The Inability to Form & Fulfill Appropriate Expectations

Blessed is he who expects nothing, for he shall never be disappointed.

– Alexander Pope

Dowshen (2010) introduces preparation as something to enjoy as much as the holiday itself, highlighting the importance of anticipation as the source of good feelings. Confidence in expectations is an important part of generating a sense of anticipation. Ariely (2009) agrees with Pope that expecting nothing is helpful in avoiding the effects of negative expectations, but he also asserts that positive expectations allow us to enjoy more, improve our perception of the world, and avoid getting nothing because that’s all we expect.

A textual analysis of the survey participants’ responses reveals that holi-delay’s primary emotional building blocks are anxiety, fear, and hope: anxiety over whether one has set adequate expectations in time to act on them, fear that this is not the case, and hope that it is still possible to have one’s expectations of the holiday fulfilled during the holiday itself. These feelings fall under Bloch’s (1995) category of “expectant emotions.” Contrary to “filled emotions” like envy, greed, and admiration, expectant emotions lack a drive toward a specific desire, instead reflecting a view of the world and a future self. This lack of a definitive drive puts “expectant emotions” in a closer relationship to time. Ngai (2005) explains that for Bloch, expectant emotions reflect a greater degree of anticipation than filled emotions do.

This specific emotional-temporal trajectory is where holi-delay diverges from the holiday blues and holiday apathy. People who experience the holiday blues have an expectation that the holiday will be lacking in some way due to, for example, the absence of a loved one, and people who experience holiday apathy don’t have any expectations at all. People with holi-delay, however, feel as though they have trouble setting appropriate expectations. Because they cannot confidently anticipate the holiday, they cannot build the scaffolding to support fulfilling their expectations.

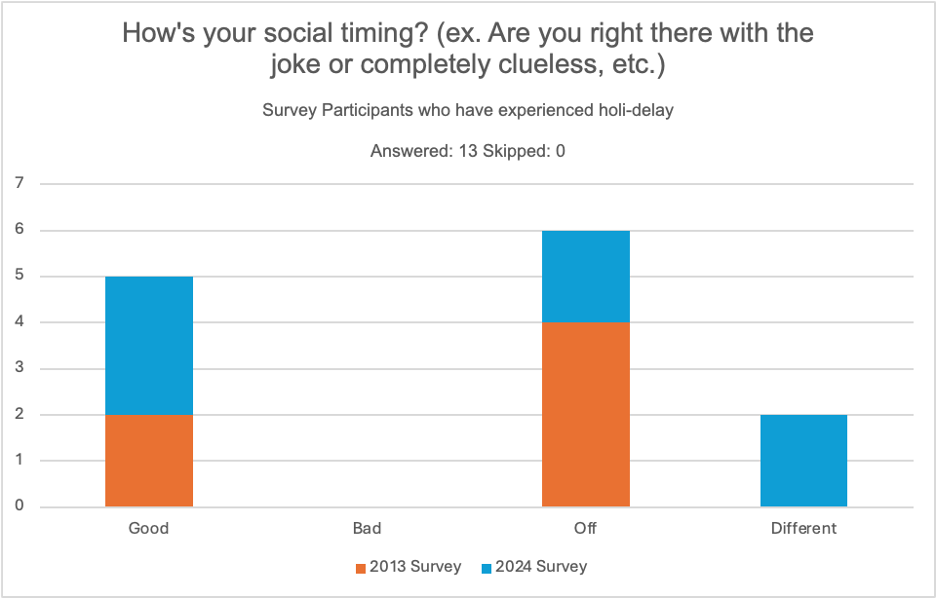

Combined results from the 2013 and 2024 survey show that 69% of people who identify as having experienced holi-delay look forward to celebrating holidays “most of the time” and that the majority of people who identified themselves as having experienced holi-delay also described their social timing as “off” or “different.” [Figure 3] This demonstrates that although people who experience holi-delay do look forward to celebrating holidays “most of the time,” their enjoyment of the holiday is affected by their social timing.

Figure 3. Combined Survey Results for “How’s your social timing?” among participants who have experienced holi-delay.

… Then Make It Happen!: Chronically Insufficient Commitment to Shared Traditions

Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to that arrogant oligarchy who merely happen to be walking around.

– Gilbert K. Chesterton

Dowshen (2010) explains that participating in traditions, caring for others, and planning and attending communal gatherings are all ways to share the holiday spirit. Xygalatas (2022) highlights the importance of shared rituals in synchronizing our movements, aligning our emotions, and connecting members of large societies together to better facilitate cooperation and create a sense of community and likeness. Holidays are a shared ritual, and people who participate in holidays enjoy the benefits of belonging to a community they feel akin to.

Holidays are an example of Turner (1982, p.41)’s “normative communitas” which he defines as a “perduring social system,” a social system maintained by a group on a permanent basis. When a group maintains a perduring system of set behaviors, they ensure this system’s continuance, as well as the mechanisms that forge enough emotional connection to justify its continuance.

Detailing the neurological landscape of engaging in familiar behaviors, Ariely (2009, p.168) references a study where neuro-scientists blind and non-blind taste-tested Coca-Cola and Pepsi. In this study, the brain activation of participants differed when the brand name of the drink was revealed or not. When the participants drank either beverage, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (“the center of the brain associated with strong feelings of emotional connection”) was stimulated. However, when the brand name had been revealed, the prefrontal cortex (an area of the brain “involved in higher human brain functions like working memory, associations, and higher-order cognitions”) was also activated. Encountering familiar people, engaging in familiar behaviors, and consuming familiar brand-named goods trigger not only feelings of emotional connection in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, but also functions like working memory, associations, and higher-order cognitions examples of which are, as Levine (2009) details, “concept acquisition, systematic decision making, evaluative thinking, brainstorming (including creativity), and rule usage.”

People who experience holi-delay might go through the motions of engaging in traditions, however, they do not actively participate in holidays. If people with holi-delay do not engage in familiar traditions or shared rituals, they miss out on the holiday spirit and a sense of community. Furthermore, they fail to log the required hours to trigger higher-order brain functions therefore preventing them from developing the necessary reasoning behind continuing to engage in such activities themselves, let alone maintain the system for others.

So How Does It Feel?: Inadequate Neuro-Emotional Response to Holiday Stimulus

The secret is to constantly build in small steps, taking advantage of small victories by using them to create your own belief system, one that can accept higher and higher levels of opportunity.

– Deepak Chopra

Dowshen (2010) notes that holiday preparation can help one identify which things put them in a good mood. People who experience holi-delay know that there is something awesome about a holiday, they just can’t seem to get their timing right so they can experience it synchronously to those around them. For people with holi-delay, fulfillment and happiness are less reliant on acquiring specific objects and more reliant on experiencing situations that meet with their internal cues, including a preference for spontaneous communitas.

In contrast to normative communitas, Turner (1982, p.41) defines spontaneous communitas as “a direct, immediate and total confrontation of human identities,” explaining that in this confrontation, we place a higher value on honesty, openness, and humility. These characteristics can increase sympathy and facilitate movement unrestricted by culturally-defined hierarchies.

Buying things is an important part of holiday preparation. In fact Ali Berlinski, a self-described “number two,” bluntly writes in her blog ali berlinski: a beautiful mess, “Like many Americans, I subconsciously associate holidays with the changing aisle displays at Target…. Without commercialism, I’m not really sure how to celebrate something” (Berlinski, 2013). You know Christmas is coming because you participate in Black Friday sales right after Thanksgiving. And when you go to the mall to buy your Christmas gifts, you hear Christmas music for the first time. Holidays reward those who participate in holidays through commercialism and disadvantage those of us who grew up with hippie parents who told us to embrace our artistic skills to make meaningful gifts for our loved ones.

Embracing the stuff-ness of holidays benefits extroverts more than introverts as extroverts are more neurochemically prone to attribute feelings of reward to their external environment (i.e. a situation you can construct), whereas introverts are more prone to feeling rewarded if their internal cues are triggered (i.e. a situation you can hope to facilitate through a proper meeting of a number of temporal, social, and material factors).

Gregoire (2013) cites a study where they gave Ritalin to introverted and extroverted college students. In the study researchers found that extroverted students associated the rush of dopamine with their environment. Ghose (2013) interpreted this study to suggest that introverts process rewards from their environment differently, attributing rushes of dopamine with an alignment with their internal cues rather than their external rewards.

Many articles about how to prepare for holidays address an extroverted public, a public who feels rewarded or fulfilled if they engage in traditions and organize their environment. However, if these articles targeted a more introverted public, they would provide suggestions about how to engage in activities which align with one’s internal cues.

Unsurprisingly, 85% of people who say they have experienced holi-delay identify as introverted in some way (as an introvert, an introverted extrovert, or an extroverted introvert), and spontaneous communitas is particularly well suited to introverts who, by nature, don’t enjoy small talk or networking or both. Gregoire (2013) notes that small talk and networking feel disingenuous to introverts, who crave authenticity in interactions.

Make Your Mood Contagious.: By Subjecting Others To Your Version of Happiness

The only man who is really free is the one who can turn down an invitation to dinner without giving an excuse.

– Jules Renard

Dowshen (2010) suggests that if you know someone in your family who experiences the holiday blues, you should invite them to join your celebration as a way to lift their holiday spirit. Most people who do not experience holi-delay see an invitation as a sign from members of their community that they are appreciated. One common complaint from holiday stewards like your stepmother and Type A friend is that they don’t get invited to enough things, and that they are always the ones to invite people around and organize everything. People who exhibit normative holiday behaviour understand that accepting invitations is one of the easiest ways to build social capital and foster connections within your community without having to do all of the planning and purchasing required to host.

However, Dowshen’s (2010) suggestion pre-supposes that the family member in question would feel better if included. As previously discussed, those who experience holi-delay prioritize spontaneous communitas and feel a sense of reward when they engage in behaviors in an environment that aligns with their internal cues. Including someone in an event you have planned because it meets your internal cues puts pressure on the invitee, because while it meets your internal cues, it might not meet theirs. Ahmed (2010) explains that those who choose not to pursue happiness in the same way may be ostracized because their choice to pursue happiness in a different way threatens the social order.

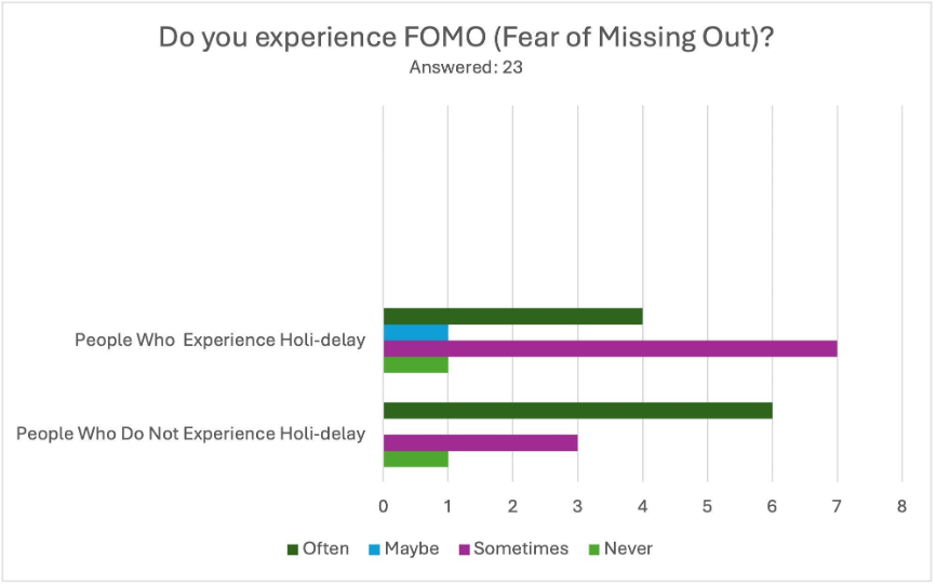

Furthermore, while attempting to make someone feel included, you may end up making them feel as if they have to abandon their preferred way of celebrating the holiday in order to participate in your event, so as to avoid a future feeling of missing out. However, the risk is negligible, since people who experience holi-delay feel a fear of missing out (FOMO) less often. While I would argue that introverts and Scandinavians have a greater understanding of how sometimes the most courteous way to respect people is to leave them alone, surprisingly, people who do not identify as having experienced holi-delay may have a better understanding of this as they feel a fear of missing out more often. [Figure 4]

Figure 4. Combined Survey results of the incidence of FOMO among people who do and do not experience holi-delay.

Here it seems important to distinguish between having holi-delay and having social anxiety. The graph above shows that while many people who experience holi-delay also experience FOMO, it is not a given. Having FOMO, or other manifestations of social anxiety (like worrying about how you always order the wrong thing at a restaurant), is different than being anxious over not having adequate expectations in time to act on them. Someone with holi-delay may feel fulfilled if they find a way to act on their chosen method of holiday celebration regardless of other activities that simultaneously occur, whereas someone with FOMO will feel fulfilled if they are unaware of those other activities or if they manage to attend.

Underlying Causes of holi-delay

Prioritizing the self as a behavior is record high with Millennials, people born between the early 1980s until the early 2000s. Although Baby Boomers are currently the largest generational cohort, Millennials are due to surpass the Boomers this decade. Stein (2013) combines National Institute of Health clinical statistics around the incidence of narcissistic personality disorder with Lasch’s (1979) broad cultural application of narcissism as a cultural disorder, to claim that rates of narcissism are higher among Millennials, connecting this claim to a media landscape that encourages them to stand out from the crowd as individuals. Individualism is the defining trait in many studies of Millennials. Clinical professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University Jill Hennessy, also attributes the greater value Millennials place on experiences that align with their individual goals with witnessing their parents struggle with financial insecurity during the Great Recession (Nelson, 2013). Perhaps holi-delay has not been discussed as a condition until now because Millennials’ individualistic tendencies have not yet dominated the socio-cultural landscape. As their numbers overtake the Boomers in coming years, the social sciences must address this newly-urgent topic.

Addendum

There have been significant changes in holi-delay’s milieu within the past ten years which are worthy of discussion, including the impact of the gig economy on social networks and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rates of introversion. Although rates of holi-delay have remained consistent [Figure 1], the coping mechanisms employed by people who experience holi-delay have become widespread social norms which, going under-examined, threaten to dismantle our social order.

Gig Economy

Since 2013, more and more people are freelance workers, and therefore more and more people have working schedules that deviate from and intersect with one another in new, hopeful, and interesting ways for facilitating spontaneous communitas. However, technological changes have had potentially deleterious effects: the gig economy gave rise to gig apps which are impacting our social networks. Armitage (2021) notes that gig apps financialize activities which used to be an expression of social capital. Instead of asking a friend to pick you up from the airport, you can call an Uber. Instead of asking your child to help you hang a shelf, you can request help through Taskrabbit. Putting a positive spin on this phenomenon, Armitage (2021) argues that those with the funds to engage with gig apps can use them to maintain boundaries with their friends and family.

berlant (2022) proposes that although it is inconvenient to be in relation with each other, humans experience an “inconvenience drive” that pressures them to keep taking in objects and interactions. If gig apps allow those who can afford it to displace their inconvenience drive, perhaps this creates an opportunity. Rather than instrumentalizing this inconvenience drive towards attending Thanksgiving with your racist uncle Michael (Weekes, 2018), this inconvenience drive could instead prompt us to reach out to new objects and interactions, finding new ways to approach our needs and wants.

Covid-19 Pandemic

In 2013, I wrote that many online articles about how to prepare for holidays address an extroverted public, and indeed most of the original references remaining from the 2013 paper align with this observation. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted how online articles discuss holidays, in part because their assumed audience has become more introverted. Khazan (2021) notes that introversion is the second most-changeable personality trait, while Rentfrow, in Bedingfield (2021), speaks to how the lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic facilitated a rise in introversion because it created an opportunity for people to discover new preferences. Perhaps articles about how to celebrate holidays over Zoom with loved ones catered to holidays celebrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the pandemic continues to affect the nature of gatherings and our approach to them, whether we identify as introverts, extroverts, or somewhere in-between.

References

Adamhuet. (2011). “What If There Were No Holidays?” 17-Year-Old Thoughts. Retrieved from http://17yearoldthoughts.blogspot.com/2011/12/what-if- there-were-no-holidays.html.

Ahmed, S. (2010). The promise of happiness. Durham, US: Duke University Press.

Ariely, D. (2009). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York, US: HarperCollins Publishers.

Armitage, S. (2021). “The help: Gig-economy apps affect more than the economy—they’re changing what it means to be a friend.” Slate. Retrieved from https://slate.com/technology/2020/01/gig-economy-apps-are-changing-friendship.html.

Bedingfield, W. (2021). “Help, the pandemic has made me an introvert!” Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/lockdown-introverts.

Bent, S. A. (1887). Familiar short sayings of great men: With historical and explanatory notes. Boston, US: Ticknor & Company.

Berlinski, A. (2013). “What’s a holiday without commercialism?” Ali Berlinski: A beautiful mess. Retrieved from http://aliberlinski.com/whats-a-holiday- without-commercialism.

Bloch, E. (1995). The principle of hope. Cambridge, US: MIT Press.

BrainyQuote. “Invitation quotes.” BrainyQuote. Retrieved from https://www.brainyquote.com/topics/invitation-quotes.

__________. “Top 10 tradition quotes.” BrainyQuote. Retrieved from

https://www.brainyquote.com/lists/topics/top-10-tradition-quotes.

Chokshi, N. (2019). “Attention young people: This narcissism study is all about you.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/15/science/narcissism-teenagers.html.

Cox, D. A. (2023). “Are generational labels meaningless?” Survey Center on American Life. Retrieved from https://www.americansurveycenter.org/newsletter/are-generational- labels-

meaningless/#:~:text=The%20truth%20is%20that%20generational,often

%20bleed%20into%20one%20another.

Chopra, D. (2012). “How to recognize life’s abundance.” Oprah. Retrieved

from http://www.oprah.com/spirit/Deepak-Chopra-How-to-Feel-More-

fulfilled#ixzz2dZXQgc2H.

Dowshen, S. (2010). “Getting in the holiday spirit.” KidsHealth. Retrieved from

https://web.archive.org/web/20141107202326/http://kidshealth.org/teen/

misc/holiday_spirit.html.

Felson, S., Fraser, M. & Watson L. (2024). “Help for the Holiday Blues.” University of Rochester Medical Center. Retrieved from https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=1&contentid=2094.

Fontyn, Y. (2017). “Beat holiday apathy by simply living in the moment.” BusinessDay. Retrieved from https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/life/2017-12-11-beat-holiday-apathy-

by-simply-living-in-the-moment/.

Fry, R. (2020). “Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest

generation.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved from

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/28/millennials-overtake-

Baby-boomers-as-americas-largest-generation.

Ghose, T. (2013). “Why extroverts like parties and introverts avoid crowds.”

Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/37427-

Extroverts-have-different-brain-processes.html.

Gregoire, C. (2013). “23 signs you’re secretly an introvert.” The Huffington Post. Retrieved from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/20/introverts-signs-am-i-

Introverted_n_3721431.html.

Jameson, F. (1971). Marxism and form: Twentieth-century dialectical theories

of literature. Princeton, US: Princeton University Press.

Khazan, O. (2021). “You can be a different person after the pandemic.” The New York Times. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/06/opinion/covid-personality-change.html.

Levine, M. D. (2009). “Higher Order Cognition.” Science Direct. Retrieved

from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/higher-order-

cognition#:~:text=Higher%20order%20cognition%20is%20composed,cre

ativity)%2C%20and%20rule%20usage.

McKay, B., & McKay, K. (2009). “11 ways to get into the holiday spirit.” The

Art of MANLINESS. Retrieved from

http://www.artofmanliness.com/2009/12/10/11-ways-to-get-into-the-

Holiday-spirit.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2005). What do pictures want?: The lives and loves of

images. Chicago, US: The University of Chicago Press.

Nelson, N. (2013). “Why millennials are ditching cars and redefining

ownership.” NPR. Retrieved from

https://www.npr.org/2013/08/21/209579037/why-millennials-are-ditching-

cars-and-redefining-ownership?utm_medium=Email&utm_source=DailyDigest&utm_campaign=20130821.

Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly feelings. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Stein, J. (2013, May 9). “Millennials: The me me me generation.” TIME

Magazine. Retrieved from https://time.com/247/millennials-the-me-me-

Me-generation.

Turner, V. (1982). From ritual to theatre. New York, US: PAJ Publications.

van Gennep, A. (1977). The rites of passage (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Weekes, P. (2018). “Caught and Other Podcasts You Should Be Listening

To.” The Mary Sue. Retrieved from https://www.themarysue.com/caught-

and-other-podcasts/.

xtremerange. (2012). “holidelay.” urbanDICTIONARY. Retrieved from

https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=holidelay.

Xygalatas, D. (2022). Ritual: How seemingly senseless acts make life worth living. London: Profile Books.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.