Marx for Cats

Preface: Specter of a Cat

As she languished in a Berlin prison during World War I, Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg often thought of her cat: “At home so many times she knew how to lead me onto the right road with her long, silent look,” Luxemburg reminisced. [1] She had first encountered the feline some years before while teaching at a socialist party school, adopted her, and given her a Hebraic name, Mimi, which means both rebellion and bitter. While her imprisonment as well as the war dragged on, Luxemburg no doubt felt both senses of the cat’s name. Her voluminous letters convey a sense of pain, yet Luxemburg never lost her rebellious disposition and she remained determined to continue the struggle and make the socialist revolution, which she helped to do upon her release, in Germany, in 1918-19.

Before and after her stints in prison, Luxemburg organized, taught, agitated, and theorized, and it was Mimi who was her comrade, a word whose derivation, from the Spanish comrada for roommate, conveys here a distinct truth.[2] They lived together, read together, talked together, and received visitors together, including Vladimir Lenin, with whom Mimi “flirted” and who returned the affection. “I get up early, work, go for a stroll, and have conversations with Mimi,”[3] Luxemburg wrote to one lover. “I kiss you, and so does Mimi,” she offered another. “Mimi and I are alone together,” she related to a friend. A student of botany, Luxemburg recorded that, “we busied ourselves with the flowers, that is, Mimi and I, she is helping me skillfully the whole time.” Mimi too had an epistolary habit: “There is always a big celebration at my house when a letter from you arrives. Even Mimi sniffs at it lovingly (she calls that ‘reading the letter’),” she responds to a political ally.

Rosa Luxemburg led a revolutionary life. But so did Mimi. And while the former’s contribution to Marxist theory and practice is well known in the annals of radical history, the latter’s is considered as merely an accompaniment, if it is considered at all.

But a specter is haunting Marxism, the specter of the cat, and the time has come for a feline critique, both of capitalism and of Marxism.

[Editor: The following is an excerpt from Leigh Claire La Berge’s manuscript-in-progress Marx for Cats: A Radical Bestiary]

***

The gambit of Marx for Cats is that the history of Western capitalism can be told through the cat and that doing so reveals a heretofore unrecognized animality at the heart of Marx’s critique and of Western Marxist critique. That animality has most often been feline, and it has been present in how Marxists have constituted the economy and imagined how the economy could be transformed from a site of exploitation into one of equality. From capitalism’s feudal pre-history to its contemporary moment of financialization, those seeking to maintain economic power as well as those seeking to challenge it have recruited cats into their efforts. Medieval kings and lords styled themselves as lions; dissidents from the medieval order were identified through their relationships with domestic cats, who likewise were considered dissidents. The first real capitalist empire, Great Britain, adopted a leonine symbol, while some of the most powerful worker actions against capitalism have been known as wildcat strikes. In the eighteenth century, French and Haitian revolutionaries were denigrated as tigers by conservatives who opposed them; in the twentieth century, the Black Panther Party insisted that capitalism was a fundamentally racist system and demanded its overthrow.

Like any text in the Marxist tradition, Marx for Cats gestures in two directions at once. In asking how our society is structured and for whom, Marxism turns toward economic history. And with the materials it finds there, it begins to conceive of how the present might have been different and how the future still could be. In offering a feline narrative of our economic past, I argue that Marxism not only has the potential to be an interspecies project but that it already is one. And in using that knowledge and those histories presented here in cat-form, I suggest that we may collectively plot a new future together, one which recognizes the work that cats have always done for Marxists and one which wonders: what political commitments can Marxists make to cats? This is less a radical history of a single species than a history of how felines and humans have made each other radical, both radically progressive and radically conservative.

Marx for Cats should be understood as what the philosopher Walter Benjamin called a Tigersprung, or a tiger’s leap into the past.[4] For Benjamin, the recollection of a historical moment functions as a kind of return to it. In the most revolutionary eruptions of both feudalism and capitalism—the peasant uprisings of the middle ages, the Paris Commune of the modern age, the queer and communist movements of the twentieth century—in each of these radical reformulations of economic power and possibility, cats were present; indeed, they were often used for said reformulation. But cats have also been called on to oppose such movements, and some of economic history’s most rapacious and atavistic rulers have passed their days in private menageries, staring into the eyes of big cats in kin-like fashion.

For Marx, too, the figure of the leap was an important one. Only for Marx, capital, not a feline, does the leaping. And capital leaps into the future, not the past, as it remakes the world through industry, wage labor and revolution. Marx returned to the leap in multiple texts, writing in his magnum opus, Capital, for example that, “so soon, in short, as the general conditions requisite for production by the modern industrial system have been established, this mode of production [capitalism] acquires an elasticity, a capacity for sudden extension by leaps and bounds.”[5] Numerous Marxists from Leon Trotsky to Mao Zedong to C.L.R. James would follow Marx and use this figure of the leap in their analyses of capitalism and of its overcoming.

Domestic cats leap as well, and their sense of poise and balance as they do so has long distinguished them among the animals that cohabit with humans. Perhaps that’s why Red Emma Goldman claimed she herself was like a cat, no matter where she was thrown from and regardless of where she was forced to jump, she always landed, she said, cat-like on her “paws.”[6]

Marx for Cats combines these multiple figurations of the leap in order to capture the moments in which cats and capitalism interact. In those openings, we may locate how felines have long been creatures of economic critique and communist possibility. We only need a certain, punctuated history of capitalism to realize this feline truth, and mine is an illustrative not exhaustive telling. In presenting the past through this sometimes disjointed feline narrative I have followed Marx, who stressed the importance of understanding history not as a seamless continuum, but rather as constituted by moments of break and rupture, of forward and backward lurches. If we are not careful to follow history’s meandering path, we wind up with a bland conception of history-as-progress which amounts to, according to Marx, a scene in which “all cats become grey since all historical difference is abolished.”[7] But if we follow the cats themselves history, hardly appears monochrome, rather we are presented with a calico palate one in which those on society’s margins and those fighting for a different social world have either sought out or have been forced into the companionship of felines.

As a guide to capitalism’s past, “cat” is hardly a transparent category, and in Marx for Cats it assumes three distinct roles. First, cats are witnesses to and perhaps makers of history: they have different and sometimes competing designs and desires. Cats benefit from certain historical situations, being welcomed indoors, for example, and suffer from others, such as the cat massacres which roiled late medieval and early modern Europe. When a new historical order is heralded in or an old one is banished, cats always seem to appear on the scene where they take positions as both vanguard and rearguard. One could be forgiven for wondering whether cats are to non-human animals what the proletariat is to all other classes, namely midwives of a different world.

Secondly, cats mark economic history as icons, symbols, indexes, and material residues of a past that really did happen. This is an archival, project, and I could not find what was not there. When the first United States President, George Washington, styled himself as a new kind of leader during the American Revolution, he decorated himself with leonine sword. When radical printer Thomas Spence designed coins for a new, socialist economy in eighteenth-century England, the one which celebrated freedom from slavery was stamped with a cat. The icon and the index can never be fully separated, and the symbolic feline history I uncover doubles as a material history in which both human and non-human actors who undertook revolutionary activity left traces of a changed world.

Thomas Spence—Cat Coin for a Utopian Economy[8]

From Niccolò Machiavelli to Adam Smith, from Friedrich Engels to Louise Michel, from Rosa Luxemburg to John Maynard Keynes, and yes, Karl Marx himself, those who have studied the relationship between state power and economic power, those who have contemplated and indeed instantiated how different that relationship could be, have used cats to do so. They have theorized using feline metaphors, they have recorded the delights and miseries of writing and organizing with feline companionship, and some of them have discussed their work with cats. I take my introduction’s compressed title from the Marxist philosopher Theodor Adorno who titled his post-World War II essay on the loss of solidary in socialism “Katze aus dem Sack”: cat out of the bag.[9]

I present here many little-known feline tales and anecdotes, and I was as surprised as readers are likely to be when I learned that American “Founding Father” Thomas Paine was accused of cat sodomy and that Paris Communard Louise Michel wrote letters to her cat from her penal exile in the South Pacific. But what is known is that humanity’s relationships with non-human animals is exploitative and unsustainable. It’s known and yet many inhabitants of the global north, and most Marxists, continue on, as if non-human animals warrant exploitation; as if industrial animal agriculture constitutes an acceptable social practice; as if Marxism need not develop to include new populations, including new species.

I have tried to take my writerly lead from Marx himself, a great lover of literature who consumed multiple styles, languages and genres. His writings have an artful and literary playfulness that often goes unremarked. Citing his inspiration and antagonist, the great German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel, for example, Marx explains that: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”[10]

Marx for Cats should be read as both. I leave it to the reader to determine the proportions of each as I present a history where class struggle and cat struggle intertwine.

It is a project intended for both novice and seasoned critics of capitalism, for dedicated cat-lovers as well as for those who are allergic. It is for those who have always wondered: Why do cats continue to endure as symbols, tropes and memes, century after century? Why are cats cherished and hated so passionately and by so many different constituencies in so many different historical moments? Why to cats bear to humans images of another economic world, from wildcat banks to wildcat strikes?

To answer such questions, we will follow Argentine Marxist Che Guevara’s haunting observation that: “At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.”[11] For too long, cats, indeed all animals, have been excluded from the reach of that loving, revolutionary embrace. The time has come to amend that exclusion. Angela Davis, a Marxist who came of philosophical age during Che’s time but is still with us today, herself a former Black Panther, tells us why such an amendment is important: “The prioritizing of humans also leads to restrictive definitions of who counts as human, and the brutalization of animals is related to the brutalization of human animals.”[12] She also suggests how to do the amending: “I think that would really be revolutionary: to develop a kind of repertoire, a habit, of imagining the relations, the human relations and the nonhuman relations behind all of the objects that constitute our environment.”[13] Marx for Cats offers one such imagining.

0.3 Inter-Species Communism[14]

0.3 Inter-Species Communism[14]

Rosa, Mimi, and Marx

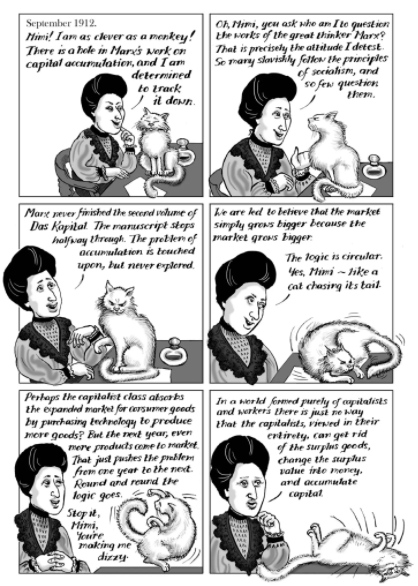

Rosa Luxemburg’s magnum opus, The Accumulation of Capital, was in fact composed with help from her cat Mimi. There she diagnosed a lacuna in Marx’s prose and solved a problem with his theory of accumulation that is still appreciated today. How, she wondered, does accumulation continue within a closed system, as Marx’s Capital seems to propose? She understood the situation in feline terms: “We are led to believe that the market simply grows bigger and bigger. The logic is circular—like a cat chasing its tail.”[15] Luxemburg’s answer departed from the feline circularity she used in her analysis. She argued there must be an outside, and only if there are times/spaces of non-capitalism, can capitalism continue its expansion, which it does through a combination of imperialism and forms of credit/debt.

Unsurprisingly, cats entered into the usual internecine party struggles as well. One comrade reprimanded Luxemburg for the victuals she purchased for Mimi, noting that the same money, the same meat, could have been used to feed the poor. She, in turn, retorted, “why are you telling me this? Don’t I do everything in my power to fight for all the poor? You shouldn’t spoil my joy with Mimi.” [16]

From Red Rosa by Kate Evans[17]

From Red Rosa by Kate Evans[17]

Plus ça change, as the French say. Even in the revolutionary moment of impending world war, animals and humans were turned against each other, and placed in competition by Marxists. Even for these small moments of interspecies comradeship, cat-loving communists were castigated. Luxemburg, in turn, issued her own critiques of her comrades, not for their feline interactions but for their support of World War I. How, she wondered, could a socialist revolution transpire if workers in one country were willing to slaughter those of another, all at the behest of nationalist, capitalist accumulation? The German Social Democratic Party, given the power of the purse, had voted to fund World War I.

As the imperialist first World War raged, Luxemburg was imprisoned for insulting the Kaiser. In prison—she had debated taking Mimi with her but decided against it—she found comradeship in a different suite of species, with birds and the odd working animal brought inside the prison walls.

She had become, in Marx’s words, vogelfrei or “bird free.”[18] Marx uses this term to isolate the particular “double-freedom” that capitalism delivers. In capitalism, one is free to do whatever one likes, but one is likewise free from anything that might help one do it. Now, in prison, Luxemburg was free from her daily life, her loves, her political problems, but also freed from the ability to realize political change. She turned to birds in her isolation and perhaps imagined flying over the walls that confined her; an amateur botanist, she made prints of the prison’s plants.

It was with the prisons’ working animals, however, that she shared her sense of captivity. In one letter, she recounted watching a Romanian water buffalo being admonished and lacerated as it delivered a cartful of goods to the prison yard. Luxemburg describes that:

…During the unloading, the animals stood completely still, exhausted, and one, the one that was bleeding, all the while looked ahead with an expression on its black face and in its soft black eyes like that of a weeping child…who does not know how to escape the torment and brutality…. How far, how irretrievably lost, are the free, succulent, green pastures of Rumania!…[We] stand here so powerless and spiritless and are united only in pain, in powerlessness and in longing….[19]

Indeed, she fantasied about a life in which she could “paint and live on a little plot of land where I can feed and love the animals.”[20] Still, as the years in prison, and World War I, dragged on, her thoughts returned to Mimi. She wondered in another letter: “Who is here to remind me of [basic goodness], since Mimi is not here? At home so many times she knew how to lead me onto the right road with her long, silent look, so that I always had to smother her with kisses … and say to her: You’re right, being kind and good is the main thing.”[21]

The water buffalos, the birds, Mimi, these animals do seem to have been Luxemburg’s comrades. And yet, her theory of accumulation and imperialism did not account for the ways in which other species have been swept up into capital accumulation and the ways in which they too might desire to break free from it. She even quotes Engels’ speciest claim that “the final victory of the socialist proletariat [will be] a leap of humanity from the animal world into the realm of freedom.”[22] In her citation of Engels, she highlights the importance of the leap. Luxemburg writes: “This ‘leap’ is also an iron law of history bound to the thousands of seeds of a prior torment-filled and all-too-slow development.”[23] We must highlight a different aspect, namely a certain irony: a cat-lover uses a feline term in her hope of abandoning non-human animals in a quest for freedom. Luxemburg famously solved a lacuna in Marx’s theory of accumulation, but this question of animal freedom, of who leaps where and from who we take our cue to leap, that constitutes a lacuna in her own life.

Amidst the toxic rubble of World War I, the Prussian Empire collapsed, the nation-state of Germany emerged, and Rosa Luxemburg was freed from prison. Along with Karl Liebknecht she founded the Spartacus League, an early iteration of the German Communist Party and one distinct from that country’s war-supporting socialists. With the war over and Germany’s politics suddenly flexible and contested, sailors began to mutiny in port after port; workers’ councils seized control of key German cities; a socialist republic was declared in Berlin. But, alas, if we have learned anything from our study of revolutions in Modernity, it is that where there is revolution, it will need to overcome a counter-revolution. As Luxemburg called for a workers’ state, she was targeted for assassination, not only by the proto-Nazi militia, the German Freikorps, but by socialists themselves. Reform or revolution became reform against revolution. It should be noted that the Freikorps, the group that actually did her in, had themselves associated women, sex-workers, communists, and cats, into a seamless category. They targeted the “proletarian women [who] are whores and cats [and] communists who live in a ‘cathouse.’”[24] Homosexuals, too, were on their list; Berlin’s gay bar at the time was called Zur Katzenmutter, “The Mother Cat.” Criminologist and psychiatrist Paul Näcke visited the establishment in 1904 and reported that it was decorated with small pictures of cats.[25]

[1] Rosa Luxemburg, The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, edited by Georg Adler, Peter Hudis, and Annelies Laschitza,

translated by George Shriver, (London, Verso, 2013), p. 143, 134.

[2] See Jodi Dean, Comrade, (New York: Verso, 2019) for the term’s longer genealogy.

[3] Luxemburg, The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, ibid.

[4] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), 261.

[5] Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, The Process of Production of Capital, in Marx-Engels Collected Works (MECW), vol. 35 (New York: International Publishers, 1996), 454.

[6] Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich, Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 381.

[7] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology, in MECW, vol. 5 (1976), 177.

[8] Collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum of Trinity College, Dublin. https://collection.beta.fitz.ms/id/image/media-143046

[9] Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflexionen aus dem beschädigten Leben, in Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, vol. 4 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1980), 82.

[10] Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, ch. 1, trans. Saul K. Padover and Progress Publishers, Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/index.htm.

[11] Che Guevara, “Socialism and Man in Cuba,” in Che Guevara Reader, ed. David Deutschmann (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2003), 225.

[12] Angela Davis, “Angela Davis on the Struggle for Socialist Internationalism and a Real Democracy,” interviewed by Astra Taylor, Jacobin, October 21, 2020, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/10/angela-davis-socialist-internationalism-democracy.

[13] Grace Lee Boggs and Angela Davis, “On Revolution: A Conversation Between Grace Lee Boggs and Angela Davis,” transcript from 27th Empowering Women of Color Conference, March 2, 2012, https://www.radioproject.org/2012/02/grace-lee-boggs-berkeley/.

[14] Drawing by An Contreras Nino, commissioned work, 2020.

[15] Cited in Kate Evans, Red Rosa. LC GET PAGE

[16] Andrew Rule, Man and Beast, Melbourne University Publishing, 2016.

[17] Red Rosa by Kate Evans, London: Verso, 2015.

[18] Marx, Capital v. 1.

[19] Full text of Luxemburg letter, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/history/winter/w3206/edit/luxemburg.html

[20] Man and Beast, ibid.

[21] https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/439-revolutionary-letters-paul-le-blanc-on-rosa-luxemburg

[22] https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1915/junius/ch01.htm

[23] Ibid.

[24] Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies v. 1 p.68-9.

[25] Clayton J. Whisnant, Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880–1945, (New York: Harrington Park Press, 2016) p. 93

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.