For Those Who Talk Back

My tongue is wild. People tell me that I’m loud, reactive, confrontational, aggressive. My friends call me loudmouth, hater, call out queen, agitator. I wear these labels as badges. My survival mechanism in situations of fight or flight or freeze is to fight. And the fight gathers at the tip of my tongue. My survival is in the custody of my tongue.

And when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

not welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.– Audre Lorde[1]

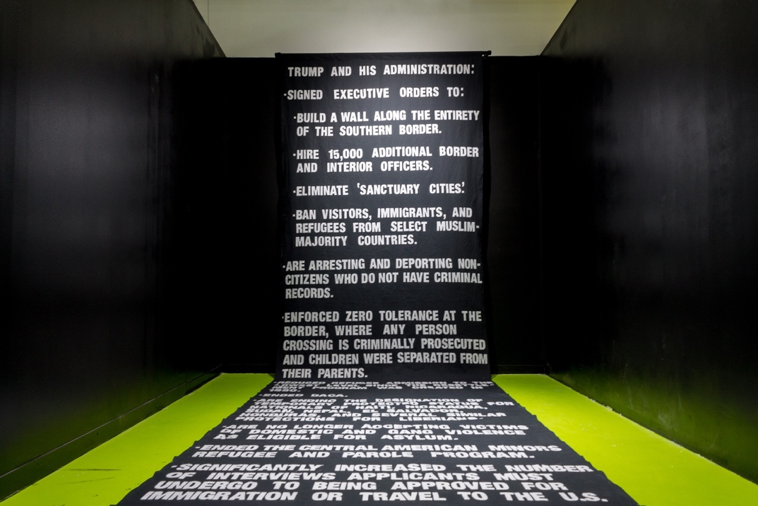

Are Our Deaths Ungrievable and Our Lives Unprotectable?, 2018, Felt appliqued onto cotton, 360 x 60 inches. Installed with “To Ward off Authorities and To Protect My Neighbors.” The banner text describes U.S. immigration policy changes that have occurred under the Trump administration using data from the Migration Policy Institute. As new policies continue to be made and amended, the banner is an ongoing project. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

…What it means to be racialized is to experience the state not as the institution that guarantees the universal protection of life but rather as one that is the very agent of death. – Grace Kyungwon Hong[2]

Neoliberal ideologies hold out the promise of protection from premature death in exchange for complicity with this pretense. – Grace Kyungwon Hong[3]

Race is both capitalism’s effect and its excess. – Grace Kyungwon Hong[4]

Racialized people have been necessary in this system, which exploits our labor but yet designates us as excess. “We were never meant to survive.” We were always meant to stay the object and never the subject. We were always meant to work and never to live.

As Grace Kyungwon Hong says, our lives are unprotectable and our deaths, ungrievable.

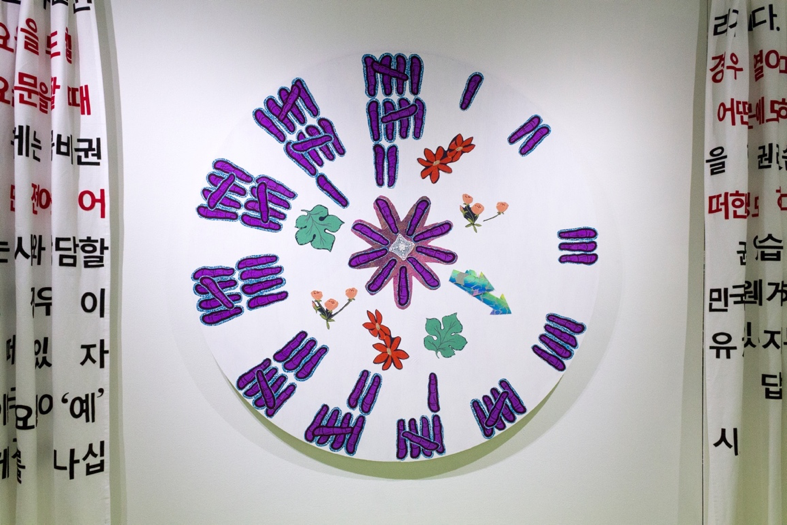

Portals to Safety, Freedom and Power (to the Past). Made with the Teen and Restorative Justice Teen Group at Hyde Park Art Center) Names of creators: Jkyra Hayes, Erika Helm, Mykah Howze, Sydni Shavers, Makeda Edwards, Alan Freitag, Jacqueline Wilson, Vachanta Simms and Aram Han Sifuentes, 2018, collaged paper and fabric on wood, 60 inches diameter. This portal honors our ancestors. The clock is made of dismembered fingers to read time, and speaks to the violence of our past but also our resilience. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

Every time I talk back to power, I feel visceral, physiological fear. A fear deep in the pit of my stomach–something my ancestors gave me to survive. My heart pounds in my chest. My knees feel weak. I get choked up.

Trauma can be a big T, for example when one is faced with annihilation, and a small t, when one feels the subtler expressions of oppression–betrayal or abandonment, an affirmation that we were never meant to survive. Both are the stuff that wears and tears on your body and soul, killing you over time.

Neuroscience suggests that when individuals face life threatening circumstances, the limbic system is activated for survival, and the pre-frontal cerebral cortex, including Broca’s area (the part of the brain responsible for verbal language) loses power. Thus, memories of traumatic events are likely to be encoded nonverbally, in sensory and somatic form. – Rachel A. Cohen[5]

I often get jealous when certain people have facility and access to words. Trauma physiologically makes it hard for one to access speech.

I was nearly annihilated repeatedly by a family member during my childhood. Twenty-five years later, I have just begun to find the words to talk about it.

Portals to Safety, Freedom and Power (to the Past). Made with the Teen and Restorative Justice Teen Group at Hyde Park Art Center) Names of creators: Jkyra Hayes, Erika Helm, Mykah Howze, Sydni Shavers, Makeda Edwards, Alan Freitag, Jacqueline Wilson, Vachanta Simms and Aram Han Sifuentes, 2018, collaged paper and fabric on wood, 60 inches diameter. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

She mimicks [sic] the speaking. That might resemble speech. (Anything at all.) Bared noise, groan, bits torn from words. The entire lower lip would lift upwards then sink back to its original place. She would gather both lips and protrude them in a pout taking in the breath that might utter some thing. (One thing. Just one.) But the breath falls away. With a slight tilting of her head backwards, she would gather the strength in her shoulders and remain in this position.

It murmurs inside. It murmurs. Inside is the pain of speech the pain to say, To not say. Says nothing against the pain to speak. It festers inside. The wound, liquid, dust. Must break. Must avoid. –Theresa Hak Kyung Cha[6]

Who is to say that robbing a people of its language is less violent than war? – Ray Gwyn Smith[7]

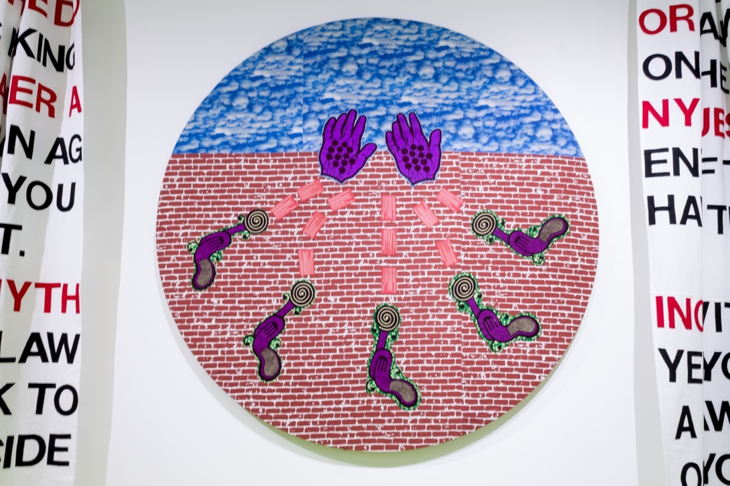

Portals to Safety, Freedom and Power (to the Present). Made with the Teen and Restorative Justice Teen Group at Hyde Park Art Center) Names of creators: Jkyra Hayes, Erika Helm, Mykah Howze, Sydni Shavers, Makeda Edwards, Alan Freitag, Jacqueline Wilson, Vachanta Simms and Aram Han Sifuentes, 2018, collaged fabric and Red Cards on wood, 60 inches diameter. This portal presents the current moment, where we are up against a brick wall. There is only a sliver of safety, power and freedom available to us. We’re trying to get there but we’re under attack. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

Oppression, colonization, exploitation, and domination takes our voices away from us. Anglos and white-adjacents who work with people of color communities often say, “we’re giving them a voice.” We already have voices that you cannot take from us. With our voices (that you have not given us), we are talking. Listen.

This is the oppressor’s language, yet I need it to talk to you. – Adrienne Rich[8]

Portals to Safety, Freedom and Power (to the Present). Made with the Teen and Restorative Justice Teen Group at Hyde Park Art Center) Names of creators: Jkyra Hayes, Erika Helm, Mykah Howze, Sydni Shavers, Makeda Edwards, Alan Freitag, Jacqueline Wilson, Vachanta Simms and Aram Han Sifuentes, 2018, collaged fabric and Red Cards on wood, 60 inches diameter. This portal presents the current moment where we are up against a brick wall. There is only a sliver of safety, power and freedom available to us. We’re trying to get there but we’re under attack. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

I remember being sent to the corner of the classroom for “talking back” to the Anglo teacher when all I was trying to do was tell her how to pronounce my name. – Gloria Anzaldúa[9]

I remember when I got time out and detention in elementary school because I recited the pledge of allegiance too loud. The teacher only reprimanded me once we were done reciting it. “You were shouting. It was disrespectful and disruptive.” But I remember that I barely spoke loud enough to hear myself over the rest of the class. Maybe it was because I wasn’t supposed to pledge my allegiance in my FOB accent. Maybe I was just supposed to move my mouth with no sound coming out–that’s what I did every time moving forward.

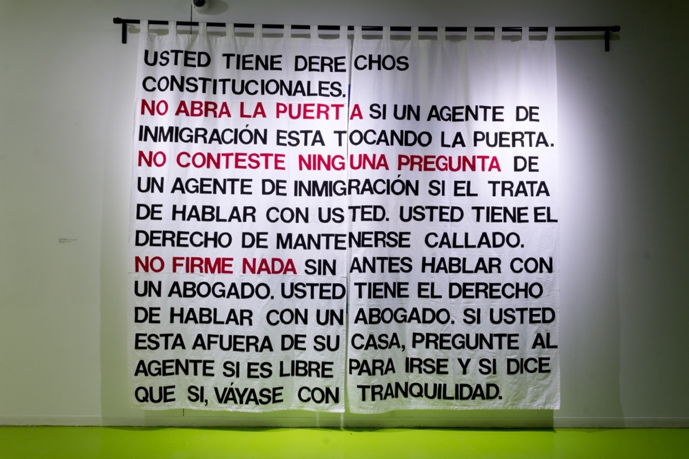

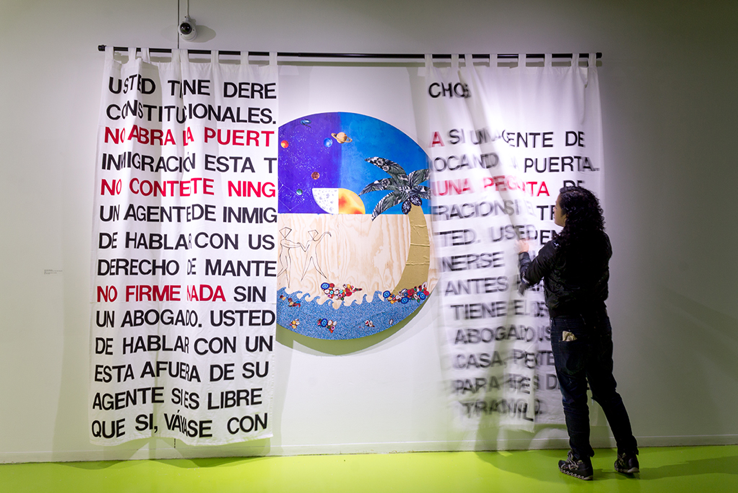

To Protect My Neighbors (Stay Safe!) in Spanish, 2018, felt, fusible web on household curtains, 98 x 114 inches. Red Cards, created by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, give immigrants Know Your Rights information in various languages so that they know what steps to take if they are confronted by authorities. I put this text on household curtains to share this information with our neighbors. “You have constitutional rights DO NOT OPEN THE DOOR if an immigration agent is knocking on the door. DO NOT ANSWER ANY QUESTIONS from an immigration agent if they try to talk to you. You have the right to remain silent. DO NOT SIGN ANYTHING without first speaking to a lawyer. You have the right to speak with a lawyer. If you are outside of your home, ask the agent if you are free to leave and if they say yes, leave calmly.” Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

Moving from silence into speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible. It is that act of speech, of ‘talking back,’ that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject—the liberated voice.” – bell hooks[10]

Speech is self-care. Speech is an act of love. Speech is resistance.

The breath can be decolonized. The breath and sound that exit the cavities of our bodies heal, transform, and liberate us.

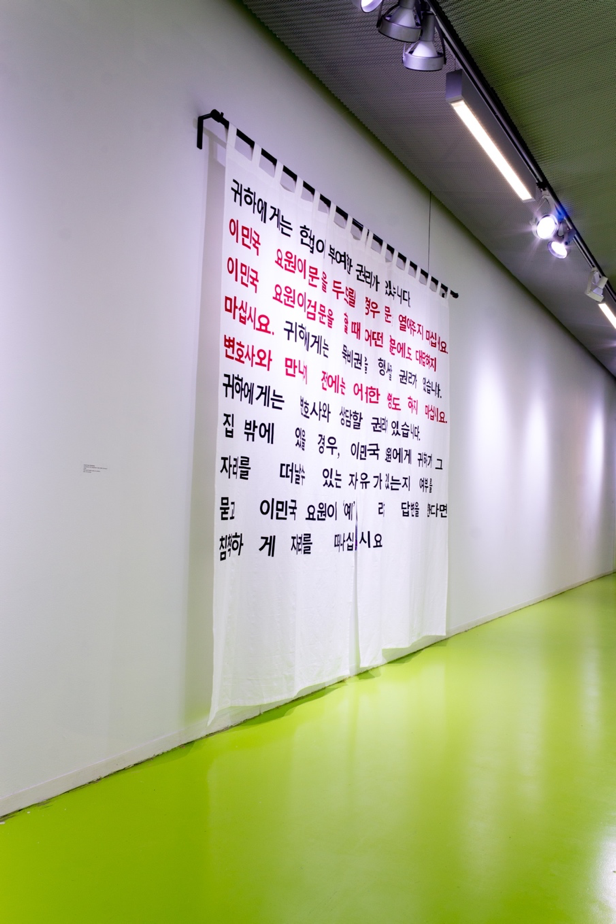

To Protect My Neighbors (Stay Safe!) in Korean, 2018, felt, fusible web on household curtains, 98 x 114 inches. Know Your Rights in Korean. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

When is speech mine and for me? Where is speech most nourishing?

For me, in Korean and Konglish.

The tongue that is forbidden is your own mother tongue. You speak in the dark, in the secret. The one that is yours. Your own…Mother tongue is your refuge. It is being home. Being who you are. Truly. To speak makes you sad. Yearning. To utter each word is a privilege you risk by death. – Theresa Hak Kyung Cha[11]

And in gossip.

Though gossip is unofficial, I do not mean to imply that it occupies a terrain that is separate or discrete from official narratives; rather, gossip is peculiarly parasitic, pillaging from the official, imitating without discrimination, exaggerating, relaying. In this sense, gossip requires that we abandon binary notions of legitimate and illegitimate, discourse and counter discourse, or “public” and “private”, for it traverses these classifications so as to render such divisions untenable. – Lisa Lowe[12]

I talk behind oppressors’ backs and in words not for them. I need witness and testimony. It is imperative to survival.

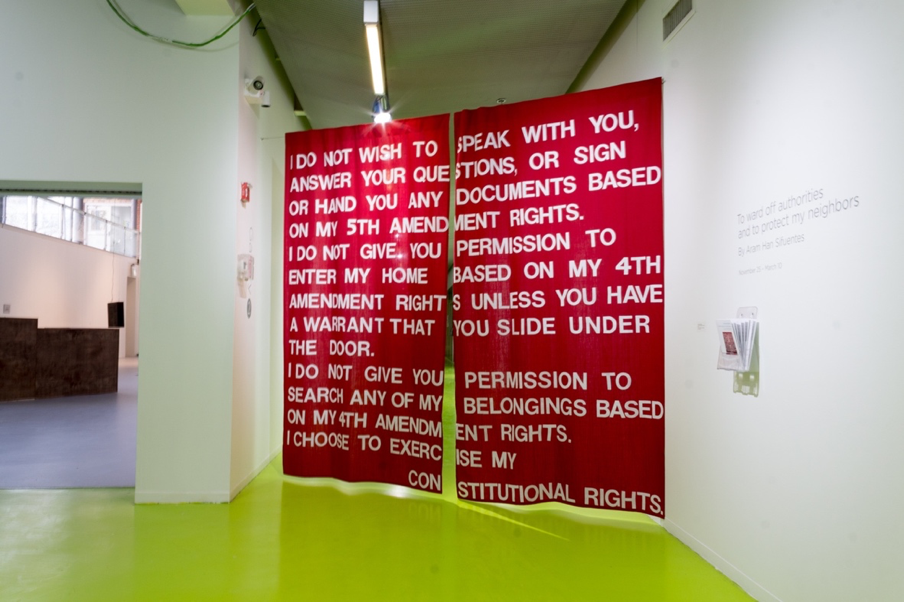

To Ward Off Authorities (Go Away!), 2018, Felt appliqued onto household curtains, 114 x 98 inches.

I appliqued Red Card statements created by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center onto curtains to claim protective spaces against authorities such as police, and particularly against I.C.E.. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

I do not wish to speak with you, answer your questions, or sign or hand you any documents based on my 5th amendment rights.

I do not give you permission to enter my home based on my 4th amendment rights unless you have a warrant to enter, signed by a judge or magistrate with my name on it that you slide under the door.

I do not give you permission to search any of my belongings based on my 4th amendment rights.

I choose to exercise my constitutional rights. –Red Card text[13]

For use, true speaking is not solely an expression of creative power; it is an act of resistance, a political gesture that challenges politics of domination that would render us nameless, and voiceless. As such, it is a courageous act–as such, it represents a threat. To those who wield oppressive power, that which is threatening must necessarily be wiped out, annihilated, silenced. – bell hooks[14]

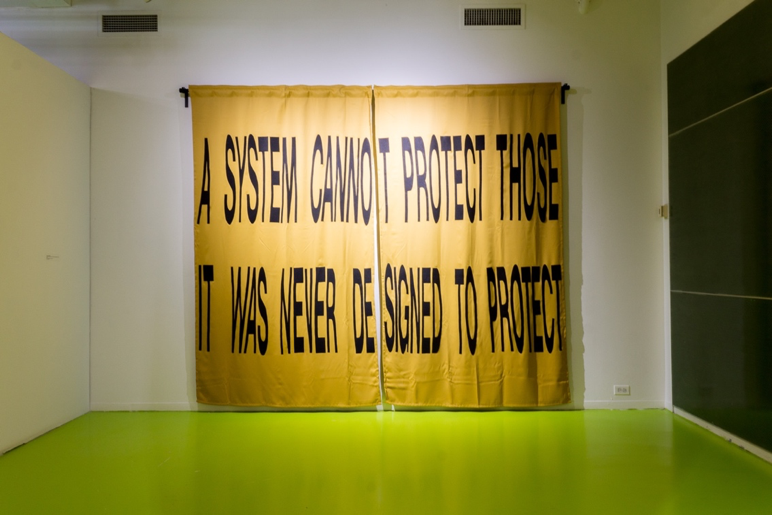

A System Cannot Protect Those it was Never Designed to Protect, 2018, felt, fusible web on household curtains, 98 x 114 inches. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

I have come to believe over and over again that what is more important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood. – Audre Lorde[15]

Speaking and talking back is always at the risk of retaliation and even annihilation.

Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out. – Gloria Anzaldúa[16]

There are risks for people who assert their constitutional rights to authorities. We fear retaliation and excessive force, but what other options do we have?

What’s here to protect us, doesn’t protect us.

A system cannot protect those it was never designed to protect.

Portals to Safety, Freedom and Power (to the Future). Made with the Teen and Restorative Justice Teen Group at Hyde Park Art Center) Names of creators: Jkyra Hayes, Erika Helm, Mykah Howze, Sydni Shavers, Makeda Edwards, Alan Freitag, Jacqueline Wilson, Vachanta Simms and Aram Han Sifuentes, 2018, collaged fabric and acrylic paint on wood, 60 inches diameter. This portal presents the future. It is a beach scene with gender-fluid, prism-headed people dancing on a beach full of gems and crystals. We’re under a sky with both the sun and moon, planets, and stars, and the Big Dipper guides us to safety as it did for fugitive slaves during American slavery. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

What can our society look like if it protects and centers us?

I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central. Claimed it as central and let the rest of the world move over to where I was. – Toni Morrison[17]

Is this too much to ask for? To ask for protection? For food, shelter, good health? For safety? For survival?

I dream up futures that aren’t for me. I dream up futures for my child that they will never see. I dream up futures for my neighbors where we can live without the constant maintenance of our T/traumas in order to fight to survive. My dreams of the future call for action.

I: speak, react, get angry, scream, protest, call out, talk back, lash out with my tongue. I want safety now—for me, my family, my neighbors, everyone. It shouldn’t be a hard ask, but it is, for a system that profits from the exploitation and annihilation of people. We’re constantly up against a brick wall that we cannot climb over. We were never meant to survive. I talk back to power because this is something I inherited from my ancestors, and something I want to nurture for my descendants to resource, even if it kills them.

[1] Audre Lorde, “A Litany for Survival,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/147275/a-litany-for-survival

[2] Grace Kyungwon Hong, Death Beyond Disavowal: The Impossible Politics of Difference (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 51.

[3] Grace Kyungwon Hong, 7

[4] Grace Kyungwon Hong, The Ruptures of American Capital: Women of Color Feminism and the Culture of Immigrant Labor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 81.

[5] Rachel A. Cohen, “Common Threads: a recovery programme for survivors of gender based violence,” Intervention 2013, Volume 11, Number 2, 157, https://www.interventionjournal.com/sites/default/files/Common_Threads___a_recovery_programme_for.4.pdf

[6] Theresa Hak Hyung Cha, Dictee (Berkeley: The Regents of the University of California, 2001), 3

[7] Ray Gwyn Smith, quoted in Gloria Anzaldúa, “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 77

[8] Adrienne Rich, “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children,” in Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, ed. bell hooks (Boston: South End Press, 1989), 28.

[9] Gloria Anzaldúa, “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 77.

[10] bell hooks, “Talking Back” in Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (Boston: South End Press, 1989), 9.

[11] Theresa Hak Hyung Cha, Dictee, 45-46

[12] Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 113.

[13] Immigrant Legal Resource Center, text of print-at-home Red Card, available at https://www.ilrc.org/red-cards

[14] bell hooks, 8.

[15] Audre Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” in Sister Outsider (Crossing Press, 1984), 40.

[16] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 77.

[17] Toni Morrison, interview by Jana Wendt, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQ0mMjII22I&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR2anDoQJJ7hmtjaQeE39qrBqpbWmlOegBNWNbnHmmSHou3bBaKJwKSYSp0

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.