Clubhouse Excavation: The United Order of Tents

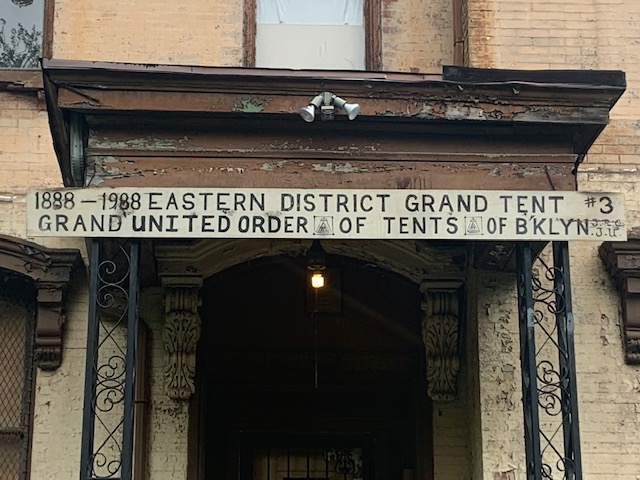

When walking past 87 MacDonough St, one’s curiosity might be piqued by a seemingly-recent urban ruin located here in the heart of the historic district in Bed Stuy, Brooklyn. The house stands majestically in a large (by NYC standards) parcel, approximately 100’ x 200’.[1] Standing there in all its historic presence, it seems to have stories to tell, announcing itself in chipped painted letters above the door: “1888-1988 EASTERN DISTRICT GRAND TENT #3 GRAND UNITED ORDER OF THE TENTS OF BKLYN. JRG JU.”

A large dead hornet’s nest seems almost glued to a front window; broken or missing panes of glass line the façade, along with tattered curtains and peeling paint. The yard speaks too—under the garbage lies a foundation from an outbuilding that has since disappeared, and the circular walkway that leads to the door seems inviting (though now only to the feral cat or rat population). The energy-saving lightbulb that is always on over the front door signals that utilities are still hooked up and being paid and visitors are still welcome, but who keeps the lights on at the entrance?

The United Order of Tents, often known as just “Tents,” is a Black women’s fraternal order that dates back to the mid-19th century. The founders were two former enslaved African women: Annetta M. Lane and Harriet R. Taylor, who were supported by two abolitionists: J.R. Giddings and John Joliffe.[2] This fraternal lodge began as a stop on the Underground Railroad and was formally organized after the Civil War with four districts across the eastern seaboard; their name referencing tents used at times by freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad. With the organization being rooted in providing assistance to those in need, “the founding members viewed the Order as a “tent of salvation” amidst the turmoil of Reconstruction and intended to uplift the African-American community through mutual-aid and personal betterment” [3] Along with the tradition in clandestine aid to the enslaved, the organization is rooted in Christian charity work; it has provided food, places to bathe, and nursing care, and it has assisted community members in receiving a proper burial[4]. It continues to provide for those in need, especially the elderly; there are several homes for the elderly run by the Tents throughout the US South.[5]

Like many other fraternal organizations of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Tents is a secret society. However, its secrecy is perhaps even more closely guarded than usual, due to its connection with the Underground Railroad, and as a result not much is publicly known about the organization and even less is known about Brooklyn’s Eastern District #3, making historical research necessary but also difficult to know where to begin. New information dug from the archives sometimes provides collaborating reference with oral histories and documentary records and at other times conflicts with them; this is the nature of historical research, and why excavation into the little-known history is so important. For this essay, Eastern District #3’s Right Worthy National Grand Queen and President of the Executive Committee, Essie Gregory, has provided a rare glimpse into this once-secret society by contributing information about their history, structure, and customs.

According to Essie and Eastern District #3’s resources, recently, it has been discovered that the earliest history of the Tents begins in 1847 in New York as an underground movement to help those in need, particularly enslaved people making their way north to freedom. However, the state of New York did not allow the organization to formally operate and the Tents moved all its activities later that same year to Pennsylvania so that Quakers could assist. With activities to aid those in need now located in Pennsylvania, the first formally organized Tent, Rebecca Tent #1, was created in Philadelphia later that same year. [6] From this point forward, additional Tents, which are groups of women known as “Sisters”, working collectively from various socio-economic backgrounds and religious affiliations formed across the eastern region of the United States.

Organizationally within the Order there are three levels: national, district, and local, which became necessary to distinguish as the Order grew in size and scope. Presently, the National Grand Encampment of Tents is made up of four districts. Each district has officers that oversee the running of the district, or regional level, which is comprised of individual local Tents. According to the latest resources from Eastern District #3 on the history of the organization, Southern District #1, organized in 1868, and includes North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia and Washington D.C.; while the states of Delaware and Pennsylvania were organized in 1847, they make up Northern District #2; Eastern District #3 formally organized in 1888 and is comprised of New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut; and Southern District #4, organized in 1922, includes only the state of South Carolina. [7] The divergence of the ordering of the Districts with the dates of organization, is an example of how the continual excavation of information provides new insights, but also poses more questions, which is difficult to investigate with publicly concealed activity like that associated with the Underground Railroad.

As the Order grew in membership and expanded geographically from the nineteenth into the twentieth century, organizational structure was required for unity[8]. A general exploration of the overall structure starting from the larger national level down to the local individual Tent level provides some insight on the responsibilities and roles each Sister provides to the Order. Today, these districts make up the national body of the organization and are operated by Superintendents (their full title is Right Worthy National Grand Superintendent), who have the final say on the rules and procedures of the organization and also serve on the Executive Board. From this group of Superintendents, one is elected to serve as leader that serves as President of the Superintendents. The President of the Superintendents serves for her lifetime, or until she steps down. If a Superintendent passes on or chooses to step down from her position, the Right Worthy National Grand Superintendent President appoints a new one. The National body convenes biennially, rotating the meetings location within the four districts and provides opportunity for all Sisters of the Order to physically unite as one.[9]

Each district is run by a committee of officers that includes the Right Worthy National Grand Superintendent, the Right Worthy National Grand Queen, The Right Worthy National Grand Deputy, the President of the Executive Board, the President of the Corporate Board, and the Worthy Leaders who represent individual Tents within the district. These officers oversee the enforcement of the constitution and by-laws within each district, with an executive board and a President who oversees the board meetings. While the Right Worthy National Grand Superintendent serving the district appoints the boards’ presidents, the Right Worthy National Grand Queen is elected by the district she served in, heads the Royal Degree Circle, and presides over all offices at the district level. Additionally, a Right Worthy National Grand Deputy is appointed by the Superintendent of each District to oversee individual Tents within that district, to guide and assist when needed. Each district within the Order also has their own physical headquarters (Eastern District #3’s is in Brooklyn).[10]

Individual Tents within each district are comprised of Sisters and led by elected Worthy Leaders and other officers. Both individual Tents and District level Tents meet on a monthly basis and then convene all together annually. [11]

Eastern District Grand Tent #3, formally organized in 1888, serves as the headquarters for all individual Tents within the northeastern part of the United States, including New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The first Right Worthy National Grand Superintendent was Sister Georgianna Queen, who served for thirty-one years in this position. Since then, an additional twelve Right Worthy National Grand Superintendents have led the District. Currently, Eastern District #3’s organization consists of a Corporate Board of Directors and an Executive Committee, headed by a President. Today, the Royal Degree Circle is led by a Right Worthy National Grand Queen and two individual Tents run by Worthy Leaders.[12]

The organizational makeup of the Tents is rooted in history and ritual, with ties running to the original formation of the organization. The titles, like “Queen,” “Superintendent,” and even the descriptive “Right Worthy” all hint at the force that early members had in their communities and the important roles and work they performed caring for those in need, including their earliest work, aiding enslaved people in reaching freedom. Additionally, the titles imply a formality and ritualization to roles within the organization, a ritual formality which can be seen in other organizations, including the numerous Masonic orders founded in the same time period. Through these rituals and roles, the organization empowered women to be forces of change in their communities. Therefore, the Tents’ physical buildings were more than just containers for their social networks; they created place, sisterhood, and heritage.

Creating Place; Creating Community

Eastern District #3’s headquarters building has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1996 (USN 04701.004141) and is located in the listed Stuyvesant Heights Historic District. The brick building, which incorporates Italianate and French Second Empire styles, was originally built in 1863 for William A. Parker, but the Tents purchased this property in 1945 from the former President of the Emigrant Savings Bank, James McMahon. While the property is currently not in good condition and looks abandoned, it is used on a regular basis. This life force is invisible to those who walk by, but it beats steadily. This house has created place through its materiality; it embodies the history and community created by this Black fraternal organization for over 150 years, a symbol of perseverance and resiliency in this community. Tents members, intent on saving it, are currently embarking on the lengthy process of historical preservation.

The symbolic strength of the Tents meeting house is rooted in its organization and structure. Community organizations and clubs have long been spaces for like-minded people to come together and socialize, but clubs are also a way to be a collective force of action. During the Progressive era in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when many mutual aid organizations were formed, clubs provided a means for marginalized groups to not only socialize but also to start reform movements on various issues, such as abolition of slavery, literacy, women’s suffrage, education, temperance, and labor. For women and communities of color that were politically or racially targeted, particularly during the period of Reconstruction, these larger national networks have been spaces of safety, providing a means for legal protection or collective activism. The women’s club movement and the African American club movement became active ways for marginalized members of the community to self-organize.[13] More well-known examples of these national club networks include organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Association for Colored Women (NACW), and the National Organization for Women (NOW). Additionally, many more regional African-American mutual aid societies, such as the Prince Hall Freemasons (originally started in Boston, MA) or the Free African Society of Philadelphia, as well as more local groups such as the Empire State Federation of Women’s Clubs working in New York State and Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn promote civic responsibility, both within the confines of the club and in the public sphere.[14]

Many clubs exemplified their mission and virtuosity through regulations and dress. Because the Tents has been a secret society since its inception, little has been written about their formal rules and dress codes. According to Essie Gregory, this code of conduct has not changed over the many years the organization has existed. Dress code for a local meeting is regular street clothes (no pants allowed). The Royal Degree District Meeting’s dress code is all-white, including a white dress or suit (no pants), white shoes, white stockings, and white underclothes (because white symbolizes purity). The presiding officer in the Royal Degree Chamber, the Right Worthy National Grand Queen, may wear a tiara and a purple robe over a white dress (it’s optional at the District but must be worn at the National). The Superintendent wears a white or black academic gown over a white dress and a mortarboard on her head; the color of the gown and mortarboard depends on the activity being performed at the meeting. The only time white is not worn is for funerals and Thanksgiving Day sermons, when former Sisters are memorialized, and then members wear black dresses or suits and black bonnets, while the Superintendent wears a black gown and mortarboard. For the biennial National Grand Encampment, the dress code is all white, except for the Superintendents, who wear academic gowns whose color (black or white) depends on the activity being performed. The Queen wears her purple robe and tiara.

Codes of conduct, including dress and laws of engagement, provide social structure. The Tents rely upon these to illustrate their organization’s constitution and to symbolize their virtues. The physical structure of the meeting space also performs these functions. While the structure today only holds District meetings during the warm months due to a lack of heat and its need of restoration, over the years the structure at 87 MacDonough Street has housed the Tents Eastern District meetings, ceremonies, and rituals, some even open to the public. Additionally, the space has been shared with other fraternal organizations for meetings, such as The Order of the Eastern Star, and gatherings for local churches. In this building, the Tents continue their legacy of physically holding space to care for others, a legacy that dates back to 1894 and the Tents’ first home for the elderly, a home that ran until 2002.[15] (In recent decades, the Tents have run yet more homes for the elderly.[16]) It harks back to founder Annetta M. Lane’s role as nurse on the plantation where she was enslaved, as well as to other enslaved African women who provided nursing care to their owner’s family in addition to their own families and enslaved brothers and sisters.

Annetta M. Lane’s family gravesite at Calvary Cemetery in Norfolk, Virginia. Photo by Kelly M Britt, January 2019.

The Tents house in Brooklyn needs historic preservation, but many factors make such a project difficult. Gentrification, and the development of the “real estate state,” against preserving the history of the many for the benefit of the few.[17] “Real estate state,” a new term coined by geographer Samuel Stein, sees real estate as a prime economic force behind the capitalist urbanization process, which David Harvey explains as a “class phenomenon where the capitalist class uses predatory practices of exploitation and dispossession over vulnerable populations diminishing, in this way, their capacity to sustain the necessary conditions for social reproduction.”[18] Essentially, it is the use of the laws of a capitalist mode of production (surplus value of commodities produced) to describe urbanization under capitalism.[19] In this state, urban planning and development promote, and in many ways encourage, displacement of lower-income communities, including many communities of color, for more lucrative urban real estate expansion projects. When we consider how urbanization affects historic spaces, even more challenges appear.

Urbanization in Historic Spaces

Collaborative historic preservation projects in urban spaces can feel like a dance competition, alternating between the slow movement of collaboration and the fast pace of urbanization. Collaborative partners dance with each other through listening, trusting, and learning each other’s rhythm. This process takes time, patience, and flexibility—a waltz in both time and space. However, urban spaces tend to hustle rather than waltz; the process of urbanization offers unique blocks to a slow project agenda in a rapidly gentrifying Brooklyn. Collaborative historic preservation projects require time for all parties to build trust with each other. Also, for non-profits or soon- to-be-non-profits like the Tents Eastern District #3, logistical aspects require extra patience and time; they need to find preservation experts to work with small amounts of funding, apply for grants, or launch fundraising campaigns, all before the actual restoration begins. This process moves much slower than cash-in-hand developers or city-supported construction.

At the heart of the Tents’ meeting house is the dance between a politics of memory and displacement and a struggle for social justice. Pearl Primus, a Trinidadian-born artist who moved to Bed Stuy in the early twentieth century and later received a PhD in anthropology, used movement as a means of communicating social justice. Historian Farah Jasmine Griffin describes the essence that Primus embodied in her 2013 book Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists and Progressive Politics During World War II:

…Primus was able to portray the challenges and restrictions of segregation…In these choreographed gestures she embodied a particularly black paradox: forced confinement and forced mobility. While the major experience of black diasporic communities has been one of mobility, migration and dislocation, these populations have also experienced forced confinement in various forms of segregation, imprisonment and enslavement.[20]

Primus’s paradox of forced confinement and forced mobility is also evident in urban space; residents are confined through racist housing policies like redlining, but urbanization requires a continual cycle of change. The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries experienced rapid gentrification, which dislocated and displaced residents that were once confined to a certain space but who grew to regard that space as home. As this preservation project slowly unfolds, several questions rise to the surface. Where do history and preservation stand within this space of urbanization? How does the immediacy of neoliberal urban planning politics intertwine with the gradual ebb and flow of a heritage preservation project? How do race, class, and gender play out in the ever-changing beat of this project? And how can the ties that bind a secret historical organization open up, connecting its preservation to a larger community?[21]

History of Displacement

Forced mobility is not new. New York City was founded on displacement, when the Dutch and English colonial settlers ousted its original inhabitants, the Lenni Lenape (Delaware Nation). This first instance of eminent domain, individual entitlement in the name of a Western capitalist agenda, was just the beginning of a process of erasure that continues today.

Many leaders in New York City have instituted displacement policies over the years. While the legacy of urban planner Robert Moses is quite well known, more recently the impact of former mayor Michael Bloomberg’s policies have also come into focus. Bloomberg’s plans to change the Big Apple into a Golden Apple came upon the heels of two disasters, 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy, infrastructure catastrophes that provided Bloomberg with the perfect climate to market his neoliberal planning policies. Bloomberg aimed to jumpstart the economy and turn New York City into a luxury destination—his new policies took aim at deindustrialized zones and neighborhoods on the margins, the ones hit the hardest by the disasters and the most desperate for help. While the neighborhood of Bed Stuy was not drastically affected by Sandy like many coastal areas of Brooklyn, much of the rebuilding and planning policies that developed post-Sandy would impact the community for years.

Historically, Bed Stuy has been comprised of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century brownstones originally built for middle-class families of primarily Irish and German ancestry. The neighborhood’s demographics shifted with the economic turn of the Great Depression and then World War II, which brought African Americans north to urban areas during the second wave of the Great Migration. Starting in the 1930s, racist housing policies such as redlining created white flight to the suburbs, and by the 1960s Bed Stuy was primarily comprised of Black residents, confined to this specific neighborhood, which over time became home.

By the early twenty-first century, due in part to the Bloomberg administration’s policies, the housing market skyrocketed. According to Trulia, a real estate website, the median price for homes in the area went from approximately $500,000 to over $800,000 from 2014 to 2018.[22] The Office of the New York State Comptroller’s report from September 2017 stated that despite nearly two-thirds of the rental apartments in the neighborhood being rent-stabilized or public housing, the median monthly rent increased by 77% from 2005 to 2015. Yet the income of long-term residents has not increased with the cost of living. The same report notes a wide disparity in median household incomes of new versus long-term residents, with new residents earning approximately $50,000 per year versus $28,000 for long-term residents. The report also mentions that more than half (55%) of households that rented in 2015 devoted at least 30% of their incomes to rent, making rent an official economic burden (2017:5).[23] This burden weighs heavily on the Tents preservation project: how can the slowness of preservation compete with the rapid economic and demographic changes that are already in motion?

Activism and Archaeology

Historic preservation and urbanization have a peculiar dance of their own, since preservation is often considered to remain static in the past while urbanization advances toward the future. At present, the main goal of the Tents is to achieve 503c.8 status, which will enable them to accept donations and apply for grants to preserve the physical space that they meet in. Once this status is granted, and funds secured and material preservation obtained, how will that in turn shape the social makeup of the organization? As the Tents in many ways are forced to forgo their long-kept secrecy, opening specific doors to the community that were once closed, will the heritage of Black women help to quell the forced displacement of Black residents in Bed Stuy? Essentially, can residents be true agents of their own mobility?

Urban Heritage Model: Weeksville Heritage Center

Heritage management, historic preservation, and archaeological projects, particularly those that focus on Black history, have been around for some time. As the reach of social media and online news increases, more of them have entered public view.[24] In Brooklyn, the historically Black neighborhood of Weeksville underwent archaeological excavations throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. Three other sites in New York have also been recently excavated: the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan in the late 1990s, Seneca Village in Central Park in 2011, and most recently the African American cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens (a site which is associated with the city’s first community of formerly enslaved Africans). While a few (like Seneca Village) were parts of academic research projects, most of these, such as the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan and the cemetery associated with St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church in Queens, were re-remembered due to direct development efforts associated with urbanization. Those development efforts were halted, or at least mitigated, due to the local, state, and federal historic preservation laws and ordinances that protect historic sites. Weeksville’s archaeology efforts have been a combination of academic efforts and necessity; it preserves the past in the face of urbanization and provides an excellent model for historical preservation.

Weeksville Heritage Center is located on the border between the neighborhoods of Crown Heights and Bed Stuy, less than a mile from the United Order of Tents house at 87 McDonough Street. Weeksville began as a nineteenth-century free Black community; it was started by James Weeks, an African American from Virginia who purchased the land in 1838 from another free African American. The first voting restrictions in New York were placed on Black men in 1821 and coincided with the adoption of gradual emancipation in the state in 1827. These restrictions required ownership of $250 worth of land and remained in place until the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 forced the state to change its voting laws. Throughout the nineteenth century, Weeksville withstood many waves of change and became a prosperous African American community filled with investors and activists. Therefore, Weeksville in itself was a form of urban resistance, providing a space for African Americans, particularly men, to own land, vote, and create a community.

In the late nineteenth century, Brooklyn was incorporated into New York City, and as amenities increased through utilities and transportation, New Yorkers’ desire to live in Brooklyn grew. While Weeksville’s legacy continued locally in Brooklyn, it became less well known to the larger public. In 1968, historian John Hurley and preservation-minded citizens joined forces, forming the Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford-Stuyvesant History, which is currently known as Weeksville Heritage Center. After Hurley rediscovered the still-extant Historic Hunterfly Row Houses in Weeksville, the organization focused on documenting the history of the community through archaeology and archival research of the Weeksville Gardens site, which was being threatened with urban renewal through the Model Cities Program.[25] The public archaeology project that involved the residents of surrounding neighborhood provided the material evidence that served as the impetus for the greater community and the Landmarks Preservation Commission to work to preserve Weeksville including the Historic Hunterfly Road Houses.

Through the Weeksville preservation efforts, these historic homes were placed in the National Register of Historic Places, a national list of preserved or eligible-to-be-preserved places, through a historic district designation. Shortly after, they became a city landmark. Since the late 1960s, the houses have undergone several archaeological investigations conducted by research academics as well as the cultural resource management projects required by federal, state, and local laws for new construction projects within the area. Through the diligent work of many on the Historic Hunterfly Road Houses, they were preserved for future generations and are now part of the Center’s multi-disciplinary museum. This museum focuses not only on the history of the Black community of Weeksville, it also uses art and civic engagement to plan for the future of the area.[26]

Despite its successes, Weeksville has also recently faced substantial setbacks. This spring, due to budget shortfalls, the Center was close to closing their doors to the public. Yet, as in the 1970s, community members and supporters rallied to the cause, helping raise over $200,000 dollars in just nineteen days in an emergency fund-raising campaign. The Center also was recently accepted into the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG), a group of cultural organizations located on city-owned property that receive consistent municipal funding, becoming the first Black city-funded cultural institution in Brooklyn.[27] While the heritage center is not a club per se, it does provide a local space for many in the community to come on a regular basis, become members and support their events, and ultimately tie the social space of the neighborhood to its historical physical space. It serves as a twenty-first century space for the African-American community of Brooklyn to gather and advocate for social, political, and economic change. In the Weeksville model, historic preservation served as a tool of resistance to the potential displacement of this vital community space, despite the constantly rising operating costs in urban spaces. Not all historic preservation efforts have such positive results. [28] [29] [30] [31] But Weeksville provides a positive model for the Tents as they begin their own historic preservation project, blocks away.

Towards an Equitable Future

Displacement, particularly in urban spaces, seems not to be going away any time in the near future. Globally, this is a phenomenon that will continue to rise, perhaps even more in spaces recovering from disaster or trying to rebuild an economy, with the 1% primarily dictating or benefiting from the efforts. Yet community spaces, such as clubs and centers like the Weeksville Heritage Center, provide a means for collective action and resistance.

Efforts to preserve the materiality and memory of the Tents’ legacy are built upon the foundation of historic preservation laws and regulations and will provide the impetus and potential funds for physical restoration. The Tents will need to change in a variety of ways, including reducing certain aspects of secrecy in order to recruit and maintain new members. By sharing their history with the public, the Tents can reach those that are interested in supporting this heritage. Community organizations can make this building a space for activism; a space for freedom; for residents to claim what Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey call their “right to their city.” This right allows us to shape the environment that we live in, as we, in turn, shape ourselves into the people we want to be. We can hold the past sacred (even the negative past of slavery, displacement and forced mobility), because our remembrance is a means to future justice.

The Tents house is a space to see if one’s “right to the city” can be partnered with what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “abolition geography,” a geography that “understands freedom as a provisional place or as one built by people with their resources at hand.”[32] This notion of freedom doesn’t erase the past but builds on it. Ta-Nehisi Coates evoked the same sentiment in his recent words addressing Congress on the case for Reparations:

The matter of reparations is one of making amends and direct redress, but it is also a question of citizenship. In H.R. 40, this body has a chance to both make good on its 2009 apology for enslavement and reject fair-weather patriotism, to say that a nation is both its credits and its debits, that if Thomas Jefferson matters, so does Sally Hemings, that if D-Day matters, so does Black Wall Street, that if Valley Forge matters, so does Fort Pillow, because the question really is not whether we will be tied to the somethings of our past, but whether we are courageous enough to be tied to the whole of them.[33]

As Gilmore says, to be tied to the whole, rather than to erase and forget the divisive past, “build[s] the future from the present, in all the ways that we can.”[34] For the Tents, Bed Stuy, and Brooklyn, only time will tell how the future can be built.

Acknowledgements:

I believe collaboration is key to most successful endeavors, and want to thank several people who made this piece possible. Robin Spencer, historian, colleague and fellow Friend of the Tents for putting me in touch with Sara Clugage regarding this piece. Julia Keiser and Zenzele Cooper of the Weeksville Heritage Center for their time, expertise and comments on Weeksville and Brooklyn history. Sara Clugage for her editorial thoughts, suggestions, and all things formatted. And last but certainly not least, to the Tents, particularly Essie Gregory for her time, patience, and the contributions that brought this all together. Team work is dream work.

[1] The usual lot size, running from Macon Street south through to MacDonough Street, is 20’ x 100’.

[2] United Order of Tents, History of the United Order of Tents J.R. Giddings and Jolliffe Union (no date).

[3] Mary Margaret Schley, 2013.”The United Order of Tents and 73 Cannon Street: A Study of Identity and Place,” All Theses (2013), 1667, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1667.

[4] United Order of Tents, History of the United Order of Tents J.R. Giddings and Jolliffe Union

[5] Kaitlyn Greenidge, “A Weekend With the Secret Society of Black Women”. Lenny Letter. https://www.lennyletter.com/story/secrets-of-the-south, 2017) accessed July 13, 2019.

[6] United Order of Tents, History of the United Order of Tents J.R. Giddings and Jolliffe Union

[7] Ibid.

[8] Schley, 1667.

[9] United Order of Tents, History of the United Order of Tents J.R. Giddings and Jolliffe Union

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] For summary of movements see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_club_movement#African-American_club_movement and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_club_movement.

[14] For an in-depth look at respectability, and the Black female intellectual, see Brittney C. Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (Urbana: University of Indiana Press, 2017).

[15] Kaitlyn Greenidge, “A Weekend With the Secret Society of Black Women,” Lenny Letter, October 6, 2017, https://www.lennyletter.com/story/secrets-of-the-south

[16] “Heritage,” United Order of Tents Southern District #1, http://www.unitedorderoftents.org/heritage/, accessed July 13, 2019.

[17] Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (New York: Verso, 2019).

[18] David Harvey in Sotirios Frantzanas, “The Right to the City as an Anti-Capitalist Struggle: Review of Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution.” Ephemera Journal 14, no. 4 (2014): 1073-1079, 1074. http://www.ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/contribution/14-4frantzanas.pdf.

[19] For more on capitalist urbanization see David Harvey’s Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (New York: Verso, 2012).

[20] Farah Jasmine Griffin, Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists of Progressive Politics During World War II (New York: Basic Civitas, 2013), 27.

[21] For example, of a study of historic place making see Mary Margaret Schley’s 2013 Master’s Thesis “The United Order of Tents and 73 Cannon Street: A Study of Identity and Place” (2013). All Theses. 1667. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1667.

[22] Trulia, “Real Estate Data for Bedford Stuyvesant,” https://www.trulia.com/real_estate/Bedford_Stuyvesant-New_York/5034/market-trends/, accessed April 30, 2019.

[23] New York City Rent Guidelines Board. 2018. Housing Supply Report. Electronic Document. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/rentguidelinesboard/pdf/18HSR.pdf, accessed January 7, 2019.

[24] For some examples of these projects, see the National Park Service website on African American Heritage for some Nationally recognized examples https://www.nps.gov/aahistory/; additionally, see President’s house in Philadelphia; and the Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith Historic Site in Lancaster, PA; and the New Philadelphia Archaeological Project, Ohio. For more resources visit the Society of Black Archaeologists at https://www.societyofblackarchaeologists.com/.

[25] Weeksville Heritage Center, “What we do: Document. Preserve. Interpret.,” https://www.weeksvillesociety.org/our-vision-what-we-do.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Caroline Spivack, “Brooklyn’s cash-strapped Weeksville Heritage Center surpassing fundraising goal.” Curbed New York, May 20, 2019, https://ny.curbed.com/2019/5/20/18632349/brooklyn-crown-heights-weeksville-heritage-center-fundraising.

[28] Japonica Brown-Saracino, ed. The Gentrification Debates: A Reader, (New York: Routledge, 2010).

[29] Brian J. McCabe and Ingrid Gould Ellen, 2016. “Does Preservation Accelerate Neighborhood Change? Examining the Impact of Historic Preservation in New York City,” in Journal of American Planning Association 82, no. 2 (2016): 134-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1126195.

[30] David Listokin, Barbara Listokin, and Michael Lehr. “Contributions of Historic Preservation to Housing and Economic Development.” In Housing Policy Debate 9, no.3 (1998): 431-478. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1998.9521303.

[31] Neil Smith, “Comment on David Listokin, Barbara Listokin and Michael Lahr’s ‘The contributions of historic preservation to housing and economic development’ Historic Preservation in a neoliberal age.” In Housing Policy Debate 9, no. 3 (1998): 479:485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1998.9521304.

[32] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Making Abolition Geography in Southern California: Interview with Ruth Wilson Gilmore, interview with Léopold Lambert.” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies 21 (2018):14-19, 57. https://thefunambulist.net/articles/interview-making-abolition-geography-california-central-valley-ruth-wilson-gilmore.

[33] Democracy Now!, “Writer Ta-Nehesi Coates Makes the Case for Reparations at Historic Congressional Hearing,” June 20, 2019, https://www.democracynow.org/2019/6/20/ta_nehisi_coates_testimony_congress_reparations.

[34] Gilmore 14.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.