Performing the Photobook

For his 2011 project 24HRS in Photos, artist Eric Kessels filled exhibition spaces with 350,000 photos, having printed all of the pictures uploaded to Flickr on a single day over a decade ago.[1] In one image of the installation, a boy grasps a lone photo from the pile he lies on. The thousands upon thousands of printed photos appear to envelop him, as they flow across the floor and into an adjacent room. Speaking at a photobook competition in 2013, photographer Alec Soth paused to reflect on this image of the boy. “I think all of us are dealing with this in one way or another,” he said as he turned to point to his slide, “For many of us, the [photo]book is a way to come to terms with this…a way of taking that pile, that flood of images, and making sense out of life.”[2]

Among photographers, Soth is not alone in turning to the photobook in the digital age. As the most common way to name books in which photography plays the leading role, “photobook” has become a rallying point for many.[3] In his overview of the medium’s contemporary fandom, scholar Matt Johnston describes the “parallel emergences” of increased interest in photobooks and the development of network technologies. He charts a timeline in which photobook histories and theoretical explorations have been published alongside the launches of MySpace, Facebook, and Twitter; new publishing ventures have come into being alongside Instagram and Snapchat; and photobook festivals, fairs, and exhibitions have continued to flourish in the age of TikTok.[4] Explaining the phenomenon, Johnston points to disenchantment with technological progress and a corresponding desire for “in real life” experiences.[5] In this way, the photobook might be seen as the photographic equivalent to the vinyl album or tabletop game. While photography has been published in book form since William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1844 The Pencil of Nature, the affordances of this form have become more apparent. Compared to the museum or gallery wall, the photobook is more intimate. Compared to the computer or phone screen, the photobook is more focused. A tactile, self-contained object, the book can absorb and captivate its readers, increasing the quality of attention dedicated to its content.

As a response to the “flood” of visual media content circulating today, the photobook offers photographers a controllable medium of presentation and viewers a contemplative mode of consumption. While the term photobook can refer to any book “that is being viewed because of the photographs inside,”[6] its use by photographers, publishers, and artists often signals a commitment to intentional design and a desire to create a distinctive aesthetic experience. In the first volume of their three-volume The Photobook: A History, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger define the photobook as “the literary novel among photographic books.”[7] They exclude from their taxonomy books that are merely a collection of a photographer’s “greatest hits.” While not everyone agrees with their attempts to police the boundaries of the term, Parr and Badger’s work does call attention to the type of books that have generated the most excitement within the developing community devoted to the medium. Aspiring to create books that are more than simple containers of images, photographers and publishers work to arrange sequences of photos to produce narrative, thematic, and essayistic qualities. They also pay attention to how the pace of a sequence can be affected by the texture and weight of the paper and the placement of images on the page. Every photo and design element plays a role in shaping the reading experience.

Because of such comprehensive design, the meaning of the photobook lies not in its individual images but in their relationship and totality. The medium thus demands a distinctive visual literacy. Curator and media scholar Briony Carlin describes reading photobooks as a mode of “accumulative apprehension…a perspectival process of discovery,” similar to shining a flashlight around a darkened area.[8] As pages are turned, more information comes into view, and readers must hold in mind each photo encountered in order to appreciate the book holistically. John Berger compares interpreting photographic sequences to noticing constellations among the stars: “One can lie on the ground and look up at the almost infinite number of stars in the night sky, but in order to tell stories they need to be seen as constellations, the invisible lines which connect them need to be assumed.”[9] In order to find insight and gain traction in interpreting a book, readers must pay close attention to details, make connections between photos, and develop a summative vision. Compared to scrolling through photos on a screen, turning the pages of a photobook slows the pace of consumption and processing, creating an environment for more thoughtful engagement with photographic content.

Although their potential for cultural intervention is clear, the reach of the photobook to date has been limited. Johnston describes how optimism about photobooks reaching a broad public has been deflated by the realization that photographers and publishers are simply making books for other photographers and publishers. He worries that the photobook community has become preoccupied “with the making and production of new, experimental and esoteric works that reinforce an exclusivity of the medium.”[10] Hoping to impress a rarefied audience, photobook makers produce works that are more and more inscrutable to those outside the community. In addition to this “spiraling sophistication” noted by Johnston,[11] photobooks are rendered inaccessible in other ways as well. In comparison to literary works, photobooks have small print runs and frequently go out of print. Already expensive when new, secondhand copies of books are often sold for several times their original value. Even worse for fans of the medium, public libraries usually only have works by the most famous of photographers, often only their “greatest hits” collections. Despite growth in the photobook industry, the medium remains an obscure one.

Fortunately, not everyone in the photobook community is as insular as Johnston describes. A decade after his 2013 lecture, Alec Soth remains a dedicated believer in the photobook, and his advocacy for the medium has expanded. Over the course of his career, he has published eleven monographs, including Sleeping by the Mississippi, Broken Manual,Songbook, and the most recent Advice for Young Artists.[12] In 2021, when his book project was interrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he began publishing videos about photobooks on YouTube. He continues the practice to this day.Soth has created over thirty videos in total, ranging in length from a few minutes to over an hour. His channel joins many others on YouTube dedicated to the medium, creating an extensive ecosystem of content that includes interviews with prominent photographers and publishers, discussions of how to produce a good sequence, trailers for soon-to-be published books, silent flip-throughs, livestreamed conversations, unboxings, and more.[13]

Drawing on selections from his extensive photobook library, which contains books both new and old, Soth’s videos stand out because of the depth of his engagement. Not only are his videos longer than those published by most YouTubers, they are also more descriptive. Rather than reviewing or summarizing books, he actively interprets them within his videos. He creates a dramatic verbal representation of the visual photobook medium—a phenomenon that I have come to call photobook ekphrasis. Because ekphrasis typically engages still images, Claus Clüver has defined it as a representation of a “nonkinetic visual medium.”[14] The existence of ekphrastic engagement with moving images, or cinematic ekphrasis, reveals the need to expand this definition.[15] Photobook ekphrasis pushes the boundaries still further.

A photobook is initially nonkinetic: It is a static object full of stationary images that do not move independently of the viewer. Its meaning and coherence, however, depend on opening the book and flipping through it. Thus, photobook critics often resort to metaphors of performance to explain the integral role of the reader: Gerry Badger compares reading a photobook to conducting a symphony, Bettina Lockemann to directing a film.[16] Photobook ekphrasis makes these metaphors literal. Soth and other YouTubers perform the photobook for their viewers. These performances depend on words, as in traditional ekphrasis, and on page-turning, which controls the flow and sequence of images. The process of page-turning varies according to the form and content of the book, and there’s a frequent back-and-forth needed to make connections across disparate parts. The power of photobook ekphrasis is that it uses words, images, and movement to democratize a medium: Expensive and hard-to-find books become viewable, and challenging and hard-to-interpret sequences become comprehensible.

While these videos of photobooks do remove the control that viewers would have if they held the books in their own hands, I think the tradeoff is worth it. Having a guide is helpful for understanding this challenging medium, especially when the aesthetic experience it creates is so foreign to contemporary media culture. The unceasing flow of digital images is abetted by content that is palatable and easy to interpret. Online, it is rare that I find myself pausing to reflect on what an image illustrates, represents, or means. Not so with the images in photobooks. Commenting on the ambiguity central to celebrated books by Paul Graham, Keiko Sasaoka, and others, Lockemann argues that their photos tend to “perpetuate their unsettledness…thus remaining present in our imagination. They challenge us to keep looking.”[17] Photobook ekphrasis calls attention to this challenge. Far from didactic, Soth’s videos dramatize his response to his own perplexity. The emphasis of photobook ekphrasis is on the process of interpretation. Soth models skills, maneuvers, and responsibilities that viewers can bring to their own readings outside of YouTube. By way of demonstration, let’s analyze two of Soth’s videos that highlight the educational impact of photobook ekphrasis: one showing how photobooks shape a reader’s perception, the other illustrating the profound shifts in understanding that can occur over multiple readings.

I first realized that I was witnessing a unique cultural phenomenon on YouTube upon viewing Soth’s “Real Time vs. Storytime.” Stumbling upon it while watching videos about photographic storytelling, I found myself both intrigued by the way Soth worked through several books to illustrate a stylistic feature and fascinated by the idiosyncratic language he used to describe its effect. The video educates viewers about a subtle distinction between two different ways of representing time in photographic sequences: one method immerses readers in the present, prompting detailed observation, while the other encourages the reader to invent narratives that connect disparate moments.[18] Beginning with the diptychs in Eve Sonneman’s Real Time, Soth points out how a small shift in perspective between two photos leads him to pay attention to what has changed. Based on the title of the book, he calls the phenomenon “real time,” but as he shows more examples in other books, he varies his vocabulary. He begins to call attention to “flickers” or “flickering time,” and later “momentary time,” “slippery time,” “stuttering time,” and “that being present in the movement of time.” This developing vocabulary captures the subjective experience of looking at books like Robert Adams’ Time Passes and Guido Guidi’s Fiume, analyzed later in the video.

Upon first glance, the photos in these books could easily be judged as bad snapshots, but Soth’s ekphrastic performance brings to life the distinctive ways of seeing developed by their sequencing. For Time Passes, which includes a series of photos of the Oregon Coast, Soth calls attention to how Adams shows the “same scene but different…almost identical but not.” As with Sonneman’s book, the subtle shifts prompt closer scrutiny of the photos, but because each photo is on a different spread, each turn of the page prompts further questioning: “Is this a different time of day? Is the light different?…Are we slightly lower in this picture?…Is this the same group of rocks?” Because of Soth’s commentary, what could seem like pointless repetition becomes a vehicle for noticing Adams’ meditative engagement with the sea. After commenting on two photos in which the horizon appears to blend with the waves and almost disappear upon flipping the page, Soth remarks, “You’re able to see subtleties like that because of the kind of deep looking that this repetition helps accentuate.”

The method of interpretation demonstrated for these “flickers” of time is not something that Soth applies over and over, ad nauseam. When the content of the photos varies, so too does his analysis. In Time Passes, Soth highlights a sequence of three photos in which Adams breaks from the incremental shifts in perspective. After reading a page of text that mentions a lighthouse, Soth turns the page to a photo of the sea and points to a small speck on the horizon, bringing the book closer to the camera so that viewers might recognize it as a lighthouse (fig. 1).

Flipping to the next photo, he says matter-of-factly, “We’re looking at a fence.” He then quickly turns the page once more to show how the perspective has backed further away from the fence, bringing the base of the lighthouse into view. Soth says the sequence makes him feel as if he has moved along the coast and around the lighthouse. After reviewing the photos again, he concludes, “This little sequence is quite subtle, but to me, that’s the beginnings of a different kind of time. So that’s not the momentary time of looking around, that’s an actual, almost narrative time.” The perception of narrative arises because of the movement represented in the sequence. Wondering about its cause or purpose, readers might invent a story to explain it. Containing only three photos, the sequence is relatively inconsequential in the broader scope of the book, but Soth’s careful explanation educates viewers about how to notice and respond to changes in content. It also prepares them to comprehend this style of sequencing in other books.

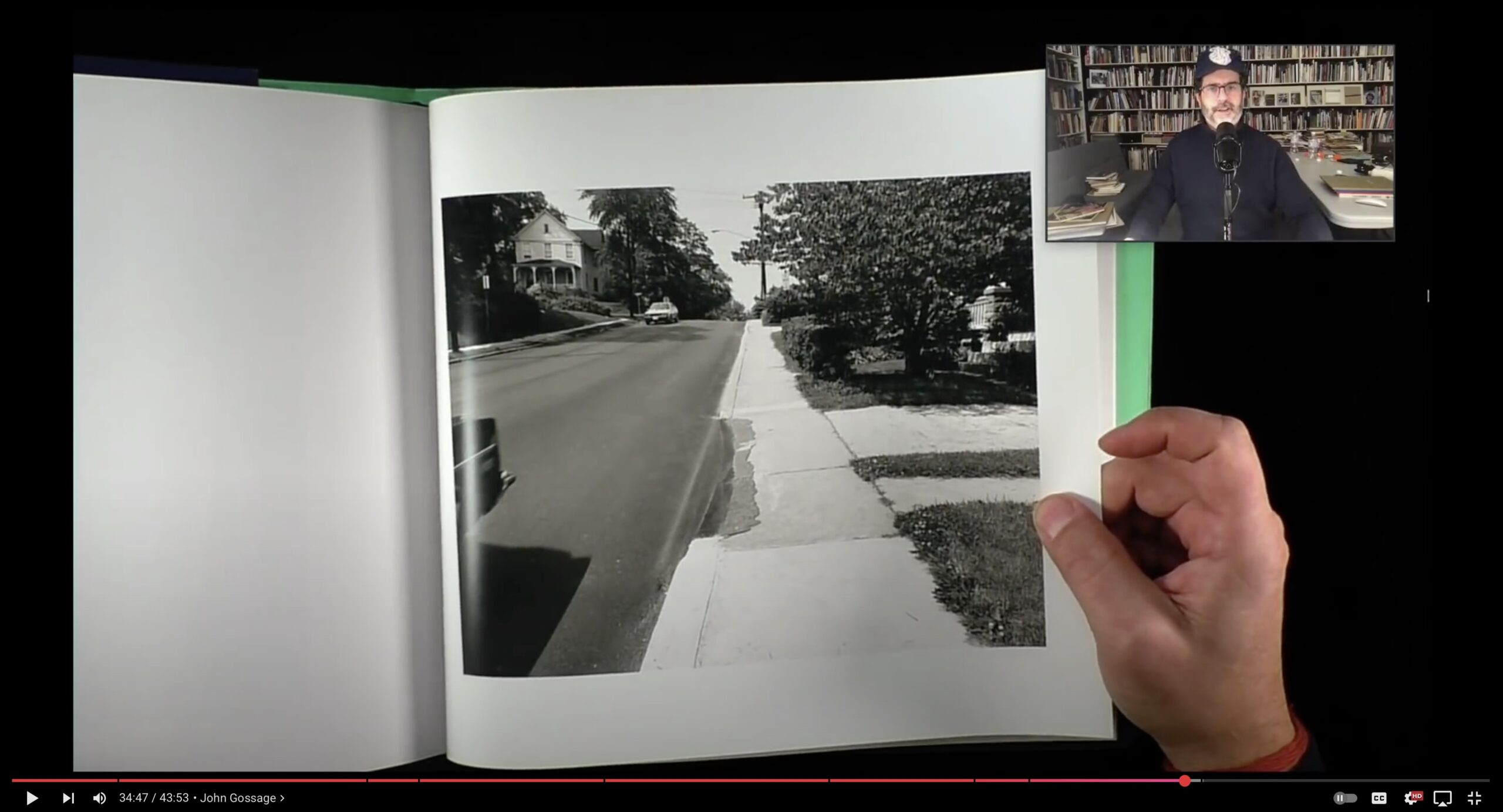

Soth’s analysis of this three-photo sequence sets up his exploration of John Gossage’s The Pond. In this book, the representation of movement through space is an essential feature; it spans the entire book. Because Soth has previously explained how the style can be perceived as narrative, he has prepared his viewers to appreciate its content. When he begins his commentary, viewers can enter the narrative relatively seamlessly, despite the fact that it depicts no people and has no characters: “So we start with this first picture, and we’ve got pavement over here, and this rocky road over here,” Soth says as he starts to slowly turn the pages. “And then this road, which is even less than a rocky road but still kind of a road. And now a footpath. And a footpath. What this is doing for me is it’s taking me on a walk. It has a bit of linear narrative movement where I have moved from the street into the brush.” As he progresses through the book, his use of pronouns shifts to the first-person plural, inviting viewers into the walk constructed by Gossage. We follow the journey from nature to neighborhood and then back into a house. While this progression could be noticed without Soth’s commentary, his use of language adds to the experiential richness of the encounter. By guiding viewers through the book, Soth steps in as the narrator of its story.

In “Real Time vs Storytime,” Soth appreciates the books holistically, but he also comments on how the medium affects his experience of individual photos. During his performance of The Pond, he pauses on a photo of a sidewalk (fig. 2).

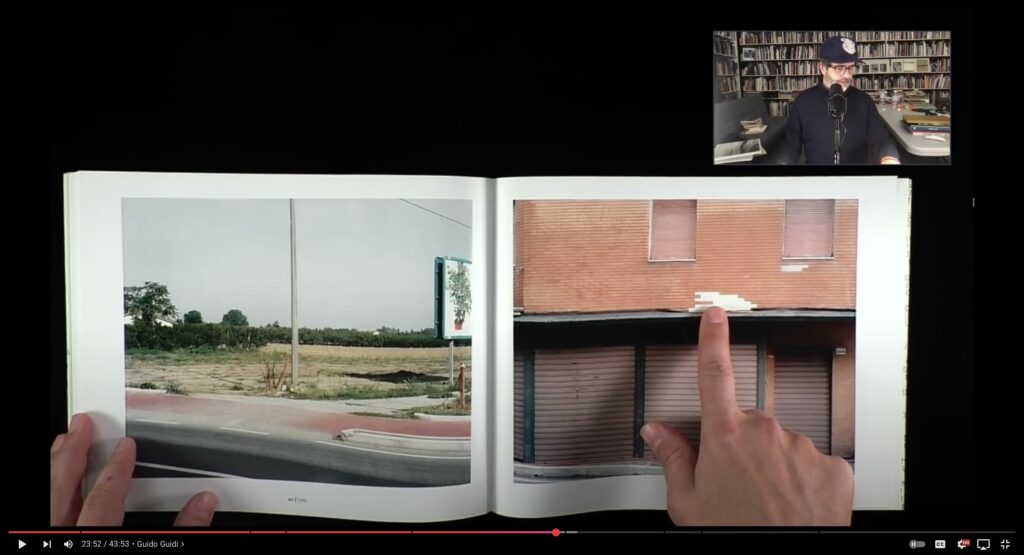

The image signals a change in setting, but Soth also finds it mundanity enjoyable: “Gossage has primed our eyes, so that we’re able to kind of, you know, look at this paving, which has been redone multiple times and kind of enjoy it. Our palette has been made sensitive so we can kind of savor this peculiar pavement job.” A similar moment occurs when Soth comes to a photo of a ramshackle building in Guido Guidi’s Fiume (fig. 3).

Lacking foreground and depth, Soth describes it as a “flat picture…the kind of photograph that I would flip right by.” However, because the sequence has altered how he approaches the images, Soth finds it worth lingering over: “I’ve been attuned because I’ve slowed down and looked more closely in the previous pictures. It feels satisfying, my senses are alive, and I’m looking at how these fake brick tiles fell off and the fact they match this tile down here, and you know, I’m experiencing it in a different way because I’ve been primed by the previous pictures.”

It is in moments like these that the function of Soth’s ekphrasis is most clearly demonstrated. He is not just creating a vivid experience of the photobook; he is also performing a distinctive mode of seeing. In “Ekphrasis in the Digital Age,” Renate Brosch suggests that ekphrasis might respond to the “hypersaturation” of images online and attempt to compensate for their diminished power to affect viewers.[19] When Soth calls attention to the priming of his senses, he appears to do just this. Brosch also notes that ekphrasis is as much a representation of a perspective as it is of a work of art, noting “its conspicuous staging of an observer’s gaze.”[20] What is unique about photobook ekphrasis, especially as it is performed by Soth, is that it dramatizes the perspective formed through interaction with photobooks, rather than foregrounding the YouTuber as an authoritative interpreter. Combining words, images, and movement, the ekphrastic performances offer evocative demonstrations of the form’s mediational power, showing the process of perspective-formation initiated by a book’s design, content, and sequencing.

By verbalizing their impacts upon him, Soth shows how photobooks might re-enchant photography. He also demonstrates that this sense of wonder is rarely achieved immediately. Several of his videos represent a journey to appreciation that involves working through confusion, uncertainty, and misunderstanding over multiple readings. In “On Saying Yes (to Jacob Holdt),” for example, he describes being “shut down” to Holdt’s American Pictures.[21] He avoided the book because he disliked its design and was uncomfortable with the photographer’s positionality. After encountering a commendatory assessment in another book, Soth reads the essays in American Pictures and finds himself admiring Holdt’s compassionate relationships with his subjects. Working through his “evolving thoughts” in real time, Soth describes how learning more about Holdt’s life and his artistic intentions alters his perception of the book, allowing him to overcome his initial negative judgment.

This turn to text and context is not uncommon. Based on his ethnographic observations of photobook readers, Matt Johnston notes a “transference of meaning-construction” as readers interact with a book. Initially, readers are guided by the design choices of photobook makers, but they gradually assume control as they assimilate a photobook with prior knowledge, make connections to outside information, and begin to “bring meaning” to the reading experience.[22] While Soth recognizes that some readers may prefer to interpret a book “purely visually” and only look at the photos,[23] he regularly brings into interpretative play the captions, notes, essays, and other paratextual information found within photobooks, as well as extratextual information found outside of them. This information allows him to wrestle with the ambiguity and indeterminacy of the medium. He demonstrates how the experience of a book can deepen over time—its meanings particularized and vivified—if readers take on the responsibility of consulting information within books or seeking it out through research.

The most dramatic of Soth’s recursive readings occurs in “Do you want to know the story behind the picture?”[24] In this video, Soth juxtaposes his distinct experiences of Waffenruhe, a book set in West Berlin, containing atmospheric black-and-white photos taken by Michael Schmidt and a narrative written by Einar Schleef. Soth first encounters the book a few years after it was published in 1987 and reads it “with zero context,” only responding to the photos. Thirty years after his first encounter, a trip to Berlin provides the opportunity to gain contextual information, an experience that prompts further study and a significant updating of his understanding. He devotes roughly equal time to both experiences of the book. Thus, rather than simply performing the “best” interpretation arrived at before the making of the video, his dramatic journey through multiple engagements highlights the contingency of any interpretation, dependent on the information considered and the interpretative method applied.

Soth begins his 37-minute exploration of Waffenruhe by describing his first experience of the book. He encountered it in the early 90s, finding a discounted beat-up copy in a museum store in Minneapolis. Excited to find an affordable book, he buys Waffenruhe after doing a quick flip-through. “Over time [I] developed an appreciation of it,” he says, “but an appreciation based on very little information. All I knew was that these were pictures of the Berlin Wall.” Although he gradually comes to appreciate some of the formal elements and learns that the title means “ceasefire,” what gives him the most traction in interpreting the book is associating it with the film The Wings of Desire, also set in divided Berlin. A fan of director Wim Wenders, Soth associates the young people photographed in Waffenruhe with those at the end of the film attending a Nick Cave performance in a hole-in-the-wall night club. The idea of “young people in clubs with this bleak landscape outside,” gleaned by associating the book with the film, provides enough thematic significance for Soth to be content with his understanding. He chooses to ignore details that would alter his fixation on the photos of young adults, such as the final photo of a middle-aged man or the text taking up the middle-third of the book. Initially, Soth ignores the text because it is in German. But even when he acquires the new English edition published in 2018, he still avoids it because of its formatting. Words fill the page from top to bottom, without paragraphing or element of relief. Acquiring the new edition does not prompt deeper engagement. Perhaps feeling a resistance similar to his attitude toward American Pictures, he simply adds the book to his collection.

Despite missing the opportunity provided by its republication, Soth returns to the book a few years later after traveling to Berlin for an exhibition of his work. While there, he visits the Michael Schmidt Archive. Speaking with its curator Thomas Weski, he becomes aware of some holes in his first interpretation of Waffrenuhe. “The most powerful thing that [Weski] told me,” Soth says, “is that Schmidt—after every project—went through a period of depression.” This detail is impactful because of its personal resonance (Soth has faced similar struggles), but also because it suggests that Soth’s interpretation of the book’s emotional atmosphere might be incorrect. The psychological insight causes Soth to move away from his prior emphasis on youthful energy: “The book is so damn moody, you know, it’s bleak…it kind of makes sense that Schmidt would be someone prone to depression.” These developing ideas about the book are backed up Schleef’s narrative, which Soth finally reads after Weski tells him that Schmidt viewed the text to be an integral part of the book and the project as collaborative from its beginning. After all, Schmidt and Schleef have equal billing on the book’s title page.

Knowing that he would be impeded by the format of the text, he photographs the pages and puts them into a single document, finding it easier to read this way. Questioning his early avoidance, he says that Schleef’s narrative “blew open the whole book for me in this whole new way.” The text is about a man, struggling with depression as he goes through a divorce, isolating himself in his apartment as he wonders what to do with the rabbit that his daughter left behind. From his conversation with Weski and his own research, Soth knows that Schmidt had grown through a divorce and that a photo of his daughter was included in Waffenruhe. Beginning to grasp the nature of the collaborative project, he connects the narrator of the story to the final photo of the middle-aged man, thus shifting his understanding of the book as being about young people on the edge of adulthood to a more melancholic reflection about aging and the waning of youthful optimism.

Worried that he hasn’t made himself clear enough, he recapitulates the change in his understanding. While summarizing his first interpretation, the one he carried with him for three decades, he opens his beat-up German edition (fig. 4).

“When I would encounter a young person like this,” he says while pointing to a young man who could have been an extra in The Wings of Desire, “I pictured Michael Schmidt being that age, sort of like one of them, one of these young creative people.” He then grabs the new English edition and places it on top of his old copy. Flipping to the final photo, he says, “In fact, he was more like this age. And in reading the story, I had this perspective that, oh, maybe Schmidt, while taking these pictures of young people, was thinking back on himself when he was younger and married and had his child and separated. And that there was a kind of a backwards-looking glance into his life at that time and a kind of somber reflection.” Switching between the two copies as he articulates these interpretations, Soth appears to associate his divergent experiences with the different editions. Both present within the frame, they represent two of the book’s potential readings.

Given that Soth bases the second interpretation on the contextual information he has acquired, one might expect him to regard it as superior. But rather than dismissing his prior interpretation, he instead argues that the book operates on two levels. “It’s a book about the wall. It’s about Berlin, there’s no doubt about it,” he says while explaining the first level. “It’s about this kind of no-man’s-land that exists after the trauma of war and during this kind of waiting period where nothing is happening. The only thing that’s happening is this kind of youthful energy bubbling up.” He then offers an equally evocative overview of the second level, guided by the insight into Schmidt’s life and focused on the story of a middle-aged man waiting for his life to change after experiencing personal trauma. Closing the cover of his English edition, which still rests on top of the German one, Soth appears to be concluding the video. As he wraps up his explanation, however, he expresses uncertainty about what he has said, “Is that true? I don’t know.” He then cracks open the book yet again and takes his viewers on an intensive exploration of the entire sequence. In this third reading, Soth focuses on how the recurring imagery of obstructed views and absent horizons creates an atmosphere of claustrophobia. This formalist account could either stand on its own or provide evidence on which the other interpretations could be based. By working through three separate readings, Soth suggests that a photobook can reveal something new each time it is opened.

Among the interpretative possibilities brought to light by engaging with a book multiple times is the opportunity to find personal connection with its subject matter. In his third reading of Waffenruhe, Soth pauses to reflect when he returns to the spread showing Schmidt’s daughter juxtaposed with a graffiti heart: “Knowing that it’s his daughter takes the work to another level, it definitely adds to my experience of the book. But that might not be the case for many others.” While he qualifies his enthusiasm for learning about Schmidt’s biography, describing his psychological approach as “sort of an American thing to do,” it is clear that the book now carries greater personal significance for him. What he does not reveal in this video but which may be a significant factor in his response is that he also has a daughter, now close in age to the young woman in Waffenruhe.[25] Part of the context shaping his response is the stage of life he is at when he encounters the book. No longer the young man excited to find a cheap copy, Soth responds to the “backwards-looking glance” of Schmidt because he now looks at the world from a similar perspective.

By elaborating upon his distinct experiences of Waffenruhe, Soth’s performance shows how a photobook can accrue meaning over time. Briony Carlin points to this aspect of the medium when she describes photobooks as a time-based medium that requires “accumulating” or “accumulative” perception.[26] The meaning of a book unfolds both synchronically—at the single point in time when one looks at it, flipping through its pages—and diachronically when one returns to it again and again. Moreover, Soth’s hesitancy to privilege a certain interpretation is, in some sense, appropriate. Newfound experiences of a book do not replace previous ones. As Carlin argues, “repeat readings with the same photobook entangle new experiences with the old. Through certain evocative objects, we commune with our past selves, those former, formative moments we have also spent holding them…prompting new insights and continued discussion.”[27] While true of other aesthetic forms, Soth shows the photobook experience to be a particularly rich one. A multi-faceted medium, the photobook is both a conceptual apparatus that rewards intellectual exploration and a designed object that can acquire sentimental value like other material possessions. The levels of meaning Soth finds in Waffenruhe are present both in its intrinsic features and in the memories the book now contains for him.

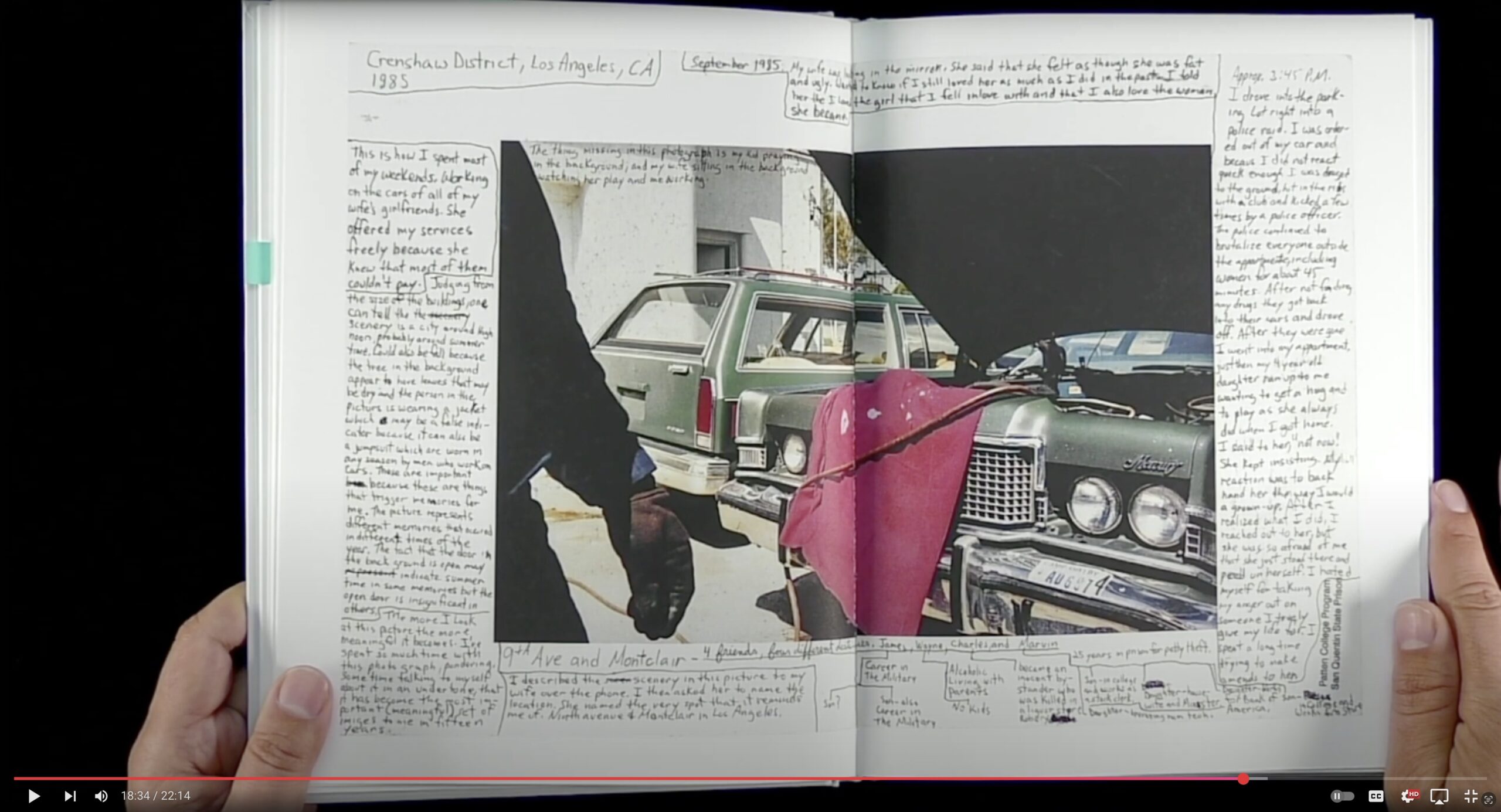

For understanding the photobook as a container of memories and impressions, Soth offers a helpful analogy in another video. Inspired by recent encounters with annotated photos (fig. 4), Soth compares reading photobooks to recording written marginalia: “I don’t write in my photobooks, but I think, in my mind, I’m writing in the books and adding layers of meaning over time. In the end, that’s so much of the value of the photography in photobooks, that story outside the picture that we bring to it, or the photographer brings to it, or someone else entirely, but that informs the picture and kind of fills it up for us.”[28]

Figure 5: An annotated image from Nigel Poor’s The San Quentin Project that prompts Soth to speak metaphorically about adding marginalia to his photobooks.

The metaphor helps make sense of why he switches between his German and English editions of Waffenruhe as he explains his different interpretations (fig. 4). It is as if he had filled them up with distinct marginalia, which he then felt compelled to consult in his performance. Each reading of a photobook offers an opportunity to add more mental notes to its pages. In addition to his YouTube performances, Soth has also modeled this cumulative experience in an annotated compilation of his own books, adding to them contextual insights and additional photos that could prompt his readers to construct new interpretations of his work.[29] His annotations might inspire readers to add their own mental marginalia.

That meanings can attach to books in this way suggests another way that the mediated experience of the photobook opposes that created by the flow of digital media. When I look at images on a screen, they rapidly replace each other. They vie for my attention before being wiped out by a video, a game, or another app. This happens regardless of my distractibility. The seamless movement of media across the screen seems to erase any ideas I might have had, any impressions I might want to savor. Each act of swiping, scrolling, and clicking is another stroke of the erasure. In comparison, the photobook offers stability. It gives viewers a place to fix their thoughts, to make connections, to contemplate, and to imagine. The durable, material form creates a context in which the power of the image depends not on its immediacy—its ability to grab my attention—but on the accumulating impressions and layers of meaning it can hold. Because of the opportunities for extended and repeated engagement, photographer Richard Benson says that the images in a photobook “can become old friends, and like the best of them reveal themselves endlessly as we come to know them better.”[30]

When I first encountered photobook ekphrasis, I was excited that I could access books that I had never seen nor heard of. I was even more excited that I did not have to pay for them. When Soth and other YouTubers ended their videos exhorting me to go out and buy the books they presented, I ignored them. The digital representation felt like more than enough. Now, I recognize the superficiality of my engagement—even with the books I do own. I have seen the books and their images, but I have not developed a relationship with them. I have no photobook marginalia to consult. Even more important than the access to photobooks is the education about them provided by these videos, which can spark a desire to unlearn the habits of seeing, consuming, and relating to images instilled by digital media. While I have often been surprised by how novels and poetry can reward multiple readings, I have rarely given photography the same opportunity. I now feel prepared to do so. I’ve recently checked out Waffenruhe from a university library. While Soth’s performance of the book was my first encounter, it will not be my last.

[1] Erik Kessels, 24HRS in Photos, accessed August 11, 2025, https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos.

[2] Alec Soth, “The Current State of the Photobook,” September 20, 2013, posted March 12, 2018, by Aperture, YouTube, 6 min., 37 sec., https://youtu.be/ZUPxXBLCLIM?si=o8NxBXdEzB9bV072.

[3] For a variety of perspectives on the cultural role of the photobook, see the questionnaires answered by photographers and publishers in Compendium: Journal of Comparative Studies, no. 2 (2022), 151-242, https://doi.org/10.51427/com.jcs.2022.0013.

[4] Matt Johnston, Photobooks &: A Critical Companion to the Contemporary Medium, ed. Emmanuelle Waeckerlé (Onomatopee, 2021), 30-33.

[5] Matt Johnston, Photobooks &: A Critical Companion to the Contemporary Medium, ed. Emmanuelle Waeckerlé (Onomatopee, 2021), 30-33.

[6] Jörg Colberg, Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book (Routledge, 2017), 1.

[7] Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, “The Photobook: Between the Novel and Film,” in The Photobook: A History, vol. 1 (Phaidon, 2004), 8.

[8] Briony Anne Carlin, “Returning to Another Black Darkness: Materiality and Meaning in Photobook Encounters over Time,” Compendium: Journal of Comparative Studies, no. 2 (2022): 62, https://doi.org/10.51427/com.jcs.2022.0016.

[9] John Berger, “Stories,” in Another Way of Telling (Pantheon Books, 1982), 284. Soth uses this quotation as an epigraph in his book A Pound of Pictures (MACK, 2022). Riffing on it later in the book, he says that he hopes his work contains “constellations of possible meaning” (67).

[10] Johnston, Photobooks &, 64.

[11] Johnston, 107-112.

[12] For a list of these monographs, visit Soth’s website: https://alecsoth.com/photography/projects. For a complete list of his publications, including collaborative books and contributions to edited volumes, see https://alecsoth.com/photography/about#publications.

[13] To get an idea of the range of photobook content on YouTube, a selection of other channels worth checking out include Jörg Colberg, Matt Day, Robin’s Book Club, The Art of Photography, Aperture, Steidl, MACK Books, Photo Book Guy, James Cockroft, unobtainium photobooks, and Book Leafing.

[14] Claus Clüver, “Ekphrasis and Adaptation,” in The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, ed. Thomas Leitch (Oxford University Press, 2017), 462.

[15] For an introductory discussion of cinematic ekphrasis, see James A. W. Heffernan, “Notes Toward a Theory of Cinematic Ekphrasis,” in Imaginary Films in Literature (Brill, 2015), 3-17.

[16] Gerry Badger, “‘Reading’ the Photobook, The Photobook Review, no. 1 (2011): 3, https://aperture.org/pbr/photobook-review-issue-001/; Bettina Lockemann, Thinking the Photobook: A Practical Guide (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022), 91.

[17] Lockemann, 69.

[18] Alec Soth, “Real Time vs. Storytime,” posted February 12, 2021, YouTube, 43 min., 53 sec., https://youtu.be/ON9pkhJaSPI?si=IzR00ayXtJdiZX5p.

[19] Renate Brosch, “Ekphrasis in the Digital Age: Responses to Image,” Poetics Today, vol. 39, no. 2 (2018): 231.

[20] Brosch, 237.

[21] Alec Soth, “On Saying Yes (to Jacob Holdt),” posted December 5, 2021, YouTube, 29 min., 51 sec., https://youtu.be/MzC4c72P1ro?si=8ynm1LSxdMnL1t_y.

[22] Johnston, Photobooks &, 150-53.

[23] Alec Soth, “Do you want to know the story behind the picture?” posted September 16, 2022, YouTube, 43 min., 36 sec., https://youtu.be/GUeS-D0onu4?si=NPYCy41XdcbQOhZ6.

[24] Soth, “Do you want to know the story behind the picture?”

[25] Soth includes a photo of his daughter in A Pound of Pictures, a project that he says started with the desire to follow the route of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train “in an attempt to mourn the divisiveness in America” (66). Thus, the parallel with Schmidt extends further: Two fathers reflecting on the complex political condition of their respective countries.

[26] Carlin, “Returning to Another Black Darkness,” 62.

[27] Carlin, 62.

[28] Alec Soth, “Emotional Marginalia,” posted November 5, 2021, YouTube, 22 min., 14 sec., https://youtu.be/6V92KOX0z1Y?si=YF-V8B6faLP1R6dT.

[29] Soth, Gathered Leaves Annotated (MACK, 2022).

[30] Richard Benson, “Afterword,” in Lee Friedlander: In the Picture, Self-Portraits, 1958-2011 (Yale University Press, 2011).

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.