Fallen Fruit

I met David Burns and Austin Young, the two artists who comprise Fallen Fruit, in 2014. I had cold called them just a few months prior with my creative collaborator, Amanda Brinkman, to see if they would participate in an exhibition we were co-curating in New Orleans in conjunction with Prospect.3 called Foodways. It was only the second pop-up exhibition she and I had curated together under our nonprofit organization Pelican Bomb, and it was scheduled to take place in a long-abandoned building on the edge of New Orleans’s Central Business District. At that point, Fallen Fruit had had solo exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Skirball Cultural Center, and the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, so you can imagine our surprise when Burns and Young agreed to reinstall a portion of an exhibition that had once taken over the Atlanta Contemporary on two temporary walls we were erecting.

We didn’t realize it at the time, but it was indicative of a working relationship and friendship that would develop over the next few years and culminate in 2018 in “Fallen Fruit of New Orleans,” a citywide suite of projects Pelican Bomb initiated in partnership with A Studio in the Woods and Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University. Together we facilitated the planting or adoption of 300 fruit trees and an exhibition, in which Fallen Fruit drew from hundreds of objects in the archives and collections of Tulane University, to celebrate New Orleans’s tricentennial and the stories of the city. On the heels of that project, I talked to Burns and Young about their practice, risk-taking, generosity, and the radical power of beauty.

CAMERON SHAW: The theme for this issue is “Summer Fruit” and fruit is literally in your name. Can you talk about the name Fallen Fruit and how you began to plant fruit trees as your artistic practice?

DAVID BURNS: Fallen Fruit began in 2004, and it was a response to a call for submissions to a publication called the The Journal of Aesthetics and Protest. It was a call for artists, creatives, and writers that posed a basic question: Is it possible to use the agency of activism without opposition? At the time there were three of us—Matias Viegener, Austin Young, and myself. We knew there were some fruit trees on certain blocks in Los Angeles, and we looked at our own neighborhood.

We walked around and we spent a couple of days making a map that was very detailed, and we discovered there were over one hundred fruit trees in public space—along property lines or hanging over alleyways—that were basically being unused, not touched. They were all probably organic and not manicured, but they were delicious and abundant. So we wrote a text, we took some photos, and we drew a map, and when it came to figuring out what this thing was called I remember Austin saying we should call it Fallen Fruit.

There’s a quote from the Bible, from Leviticus. The quote basically says not to the take from the edges of your field or your pasture and to leave the fallen fruit for the passersby. And so long, long ago that set the tone for the work we make and gave us the impulse to explore the boundaries of public and private space, the agency of goodwill, and the capacity for community.

CAMERON: You guys have been invited into communities around the country, including New Orleans, where we worked together. The practice has evolved beyond mapping existing trees in your neighborhood to working with museums and public agencies to plant parks and trails of fruit trees. How has the process of working with community partners expanded the project for you or your vision of it?

AUSTIN YOUNG: We started by mapping fruit trees, and in our neighborhood—Silver Lake—we noticed pretty fast that the maps got popular—that those trees were all picked at the fence line. We started realizing we needed to add to this resource, so we started doing public fruit tree adoptions where we would give a fruit tree to anyone who agreed to take care of it and plant it in a space where it could be shared. It was at these kind of public events, where we invited the public to come together, that everyone would start talking about how fruit was so important to their family and their family history. Everyone has stories about their grandmother or how she makes different recipes or just about planting fruit trees at their family home.

We quickly learned that fruit is not just an object. It’s a part of the fabric of our families, our history. And it goes deeper than that into our myths, our different cultural origin stories. So that’s why when we got invited to do a show at LACMA [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art] we decided to create an exhibition where we arranged the permanent collection by fruit. That was the first time that we started doing this kind of looking at fruit in a different way. It became more than just planting for us. It became the world and a way that we’re all connected—a way to see that we’re all connected and we’re all connected by fruit.

Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns, Matias Viegener and Austin Young), eatLACMA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Installation of works of art from the permanent collection organized by fruit types on top of a custom-designed wallpaper pattern. Dimensions variable. Installation view, 2010

CAMERON: So the work that we did together in New Orleans included planting two fruit parks, holding three tree adoption events, as well as producing an exhibition. It incorporated both sides of Fallen Fruit’s practice—the museum practice of re-presenting archives and the public space practice of planting fruit trees and creating community gatherings like a pickling party. And I hate to think about them as distinct because I know they’re so connected, and that of course shows in New Orleans and other places like Portland where you’ve done both. You’ve now worked in so many different cities. I’m curious the ways in which New Orleans differed for you, or some of the things that you learned that were specific to the place.

AUSTIN: The idea [for the show at Newcomb] actually stems from us looking at the way fruit moves around the world with culture, and, with colonialism, how nations conquer nations. This idea of the way that fruit is moving along with people really solidifies to us how intertwined fruit is with culture and how things end up in a place. Like, for example, how most of the fruit trees in New Orleans don’t come from there. They’re native to other places. We began to feel strongly that as we worked on fruit, we were working on the way that people end up in a place.

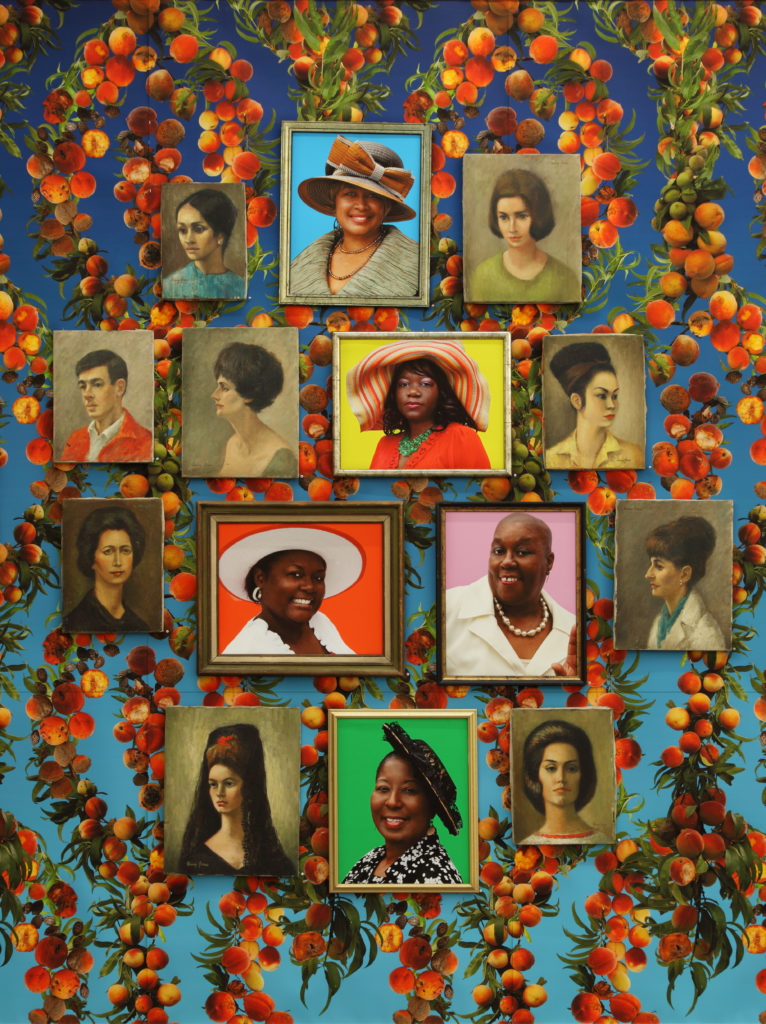

New Orleans is in more than one way an extension of what we did in Atlanta, just because Atlanta was such an important departure for us from thinking about fruit to thinking about culture. You know, everyone in the South—when you meet them—has a story to tell. Also we were thinking about the saying that someone is “a peach.” So, we came up with this idea of collecting portraits from people and institutions.

CAMERON: Atlanta was my first introduction to your work and it was before you even installed there. I was talking with Stuart Horodner [then Artistic Director of the Atlanta Contemporary] and I was touring the gallery. It was empty at the time, but he was talking about how you were planning to install your work in the space. He was so passionate about it that I was like, I gotta look these dudes up. That’s what made us invite you to New Orleans the first time to partially install or adapt that exhibition from Atlanta in 2014. It was just so incredibly beautiful–the ways that it united the wallpaper you design and objects with such a clear and deep cultural history. It also contained such fabulous portraits taken by you, Austin. I’ll never forget the first time I saw the photographs of those church ladies in the hats that you took. They were peaches. They were so expressive. I thought, wow. These guys are really on to something beautiful that gets at when people are feeling and acting beautiful. I think this is a challenging moment to think about that because it feels like more often than not our newsfeeds are filled with people acting ugly rather than acting beautiful. So I think your work does something special in that regard.

AUSTIN: I think beauty is radical right now.

CAMERON: It is. Absolutely. I think that’s what is so amazing about the lemonade portraits, where you hand people a piece of fruit and a Sharpie and ask them to draw themselves. It is allowing people to express what’s unique and beautiful about themselves in the most basic ways.

Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young), Fallen Fruit of New Orleans, Lemonade Stand, Public Participatory Project. Documentation Image, 2018

DAVID: May I respond to what was just articulated and put it onto a chronological timeline? I’d like to run through a complicated series of events that Austin introduced that I think is really valuable. When we worked at LACMA, which was in 2010, we installed the wallpaper in the room and then with a lot of convincing and, you know, negotiating, we were able to install selections from the permanent collection according to fruit on top of it. Which is something a museum like LACMA typically would never ever do. It’s an encyclopedic institution and a public institution, so there’s an area for ancient art, decorative arts, a European collection, a Japanese collection, Chinese, Pre-Colombian, etc. All of these different categories or bodies of knowledge are separated into different levels, floors, buildings.

What we asked to do was to conflate all of that and organize it by apple, banana, orange. We installed it and people loved it. They went crazy because they’ve never seen [Roy] Lichtenstein next to a Dutch still life. It’s not how it’s shown in textbooks. And in these ways we are able to have a new understanding about fruit. That it is something that is an object and a subject at the same time, and it’s symbolic. It’s a very rare thing that you can have something that you can move forwards and backwards in history and still just be a banana. And at the same time a banana is always a joke regardless of language boundaries or age and it’s always about permission, about ritual, about rights. So in those ways we have this profound shift and then a few years after that we were talking about Atlanta.

And in Atlanta, we met Stuart and we were running around doing our research and people kept telling us story after story about their families. We realized we couldn’t just do fruit on the walls. We had to listen to the people. And what we did was create The Fruit Doesn’t Fall Far From the Tree. That’s the title of the piece, and it’s portraits of five generations of people in Atlanta that are organized from birth until death. When you walk in the space you see images of women in labor and childbirth and newborns all the way through proms and birthday parties, getting married and having jobs. In those ways we started to understand the narrative of how personal and objective knowledge come together and change things in ways that I understand art to do. It gives you an understanding and a shift in the way you see the world around you.

CAMERON: I frequently go back to John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. He talks so much about the ways in which seeing images next to one another influences our modes of understanding them. And I think that’s equally true in the LACMA setting as it is in Atlanta for different reasons but it expands the way we look at any single image–to see it in dialogue with images both like it and unlike it. I think Atlanta is such an interesting example of that, especially in the ways in which it dealt with the city’s history of civil rights and race. That also comes to the fore in the New Orleans show in the ways y’all have thought about separating the space to think about images of masculinity and images of femininity, as it relates to the history of the site—Newcomb being a women’s college on the campus of Tulane. Images say different things when we look at them in different groupings. That’s something that’s really exciting about that installation for me.

AUSTIN: Thank you. It was really fun to create that installation and to actually–in a sense–let that installation create itself. I think it naturally wanted to pull itself into a men’s room and a women’s room, which I think is a way that we work that is radical. We don’t really come to a new project knowing what we’re going to do. We might have an idea of what we might do, but we try to step back and let the work find its own way and it’s always a risk for the people we’re working with, as well as us. We’re putting ourselves on the line. That creates a sort of living, breathing artwork. The other thing I have to say that I’m really getting in touch with is how radical beauty is in contemporary art. It’s been out of fashion I feel like for some time. One of our intentions is to create space that creates joy and light when you enter that space. We’re into this idea of transforming a space to become a space that holds a different kind of energy for people and you know it might be an energy of joy, delight, or in Newcomb’s case there’s a lot of different feelings you could feel as you went around the room.

Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young), The Fruit Doesn’t Fall Far From The Tree / Portal #7 – Women Of Society. The Atlanta Contemporary, Installation view, 2013

CAMERON: I’m curious as to why you think beauty has gone out of fashion.

AUSTIN: I think for me personally, trying to navigate the contemporary art world, that people really get stuck on academia and also how their work is going to fit into the art world. I think these kinds of things can pull you away from creating. I’m just speaking for myself–of just creating art that’s really true to yourself.

CAMERON: I want to talk more about the risk of working in public space and how you guys think about that, especially when you’re approaching cities where you have a limited amount of time to work. You’re trying to make connections that are meaningful and that takes time, but there’s also a pressure on you all and the organizations that you are working with to develop the project at a certain pace. So, I’d love to talk a little bit more about risk and how you define that word in the context of your practice, especially the work in public space and the planting work.

AUSTIN: There’s something about this question that’s really connected to the idea of beauty and creating a space for joy, love, and light. We do that in our public engagement and planting projects. When we do our lemonade stand, people that come and participate feel really welcomed. They feel like they’re being seen when they draw their portraits and I take their picture. There’s a sense of connection that we fostered. I feel it. It’s very palpable and people that come to our events feel it.

DAVID: You know what? Risk implies that something is going to go wrong. From the origin story and how Fallen Fruit was founded as an idea, it was a response to a question: “Is it possible to be inclusive?” And hyperbolically inclusive, so that’s always been our mandate. Like is it taking a risk when everyone is welcomed? I mean I think it’s a risky thing to do because what if you get rejected? It’s like asking someone out on a date or whatever. You know I think if you ask the whole world out on a date, the whole world’s going to say, “Oh my god. Okay.” I don’t think that we approach something with this idea that we’re taking a risk. I think we’re taking a leap of faith, which is different.

AUSTIN: But there are times when we’re taking an actual risk. Look at what happened in our project together in the Lower 9th Ward. We planted and then a major freeze hit.

CAMERON: Yes, we had the freeze; we had issues establishing our water source, and even vandalism at that site. Whereas our fruit park across town in Gentilly with the Department of Parks and Parkways progressed without a hitch. That’s not ideally how you want a project to turn out, but does that mean that the project isn’t successful or does it mean that there are new adjustments required and new discoveries made?

AUSTIN: The main risk I can see is other people’s expectations. But I think that as an artist you have to be fearless…you have to be scared and you just do it anyways.

DAVID: I one hundred percent agree with Austin. You have to feel the fear and do it anyway.

CAMERON: Speaking of fear, the work that you created for the 21c Museum Hotel in Louisville, Kentucky, ended up attracting controversy. A local reverend came forward, on behalf of a group called the African American Think Tank, to demand an image be removed from your installation for the negative way it depicted a black man. This was a clear example of multiple readings of the work, as well as an accusation of harm caused. How did you respond and what were your takeaways?

Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young), Fallen Fruit of New Orleans, Public Fruit Tree Adoption. Public Participatory Project, Documentation Image, 2018

DAVID: We often use what other people call found objects. We don’t think of them as found objects. These are carefully selected objects that look random. What we understand we’re making is ultimately a mirror. When we did The Fruit Doesn’t Fall Far From the Tree in Atlanta, it wasn’t just hundreds of portraits of people across five generations from birth until death. That’s the literal translation. What you saw on the walls instead was a history of a city—with its racism, classism, and misogyny. People would walk in and get mad or laugh. When there’s an emotional response to something, that’s a powerful moment and that’s what art is about I think—learning about yourself and learning about the world. That’s what it’s supposed to be. That was my preface.

What I think I’m being asked about is something that’s hard to navigate, which is the way that we’re taught to look at something and the way we’re taught to learn. The experience in making work for us is truly about carefully crafting a mirror or a kaleidoscope—something that is optical that changes your depth of perception and understanding. In the case of Louisville, yes, there were things on the wall that were extraordinarily racist and they were difficult images for both Austin and me. And we decided not to take them out of the installation just because we had a hard time with them.

We understood as artists that we need to “take that risk” we talked about, which is to have the faith that including difficult subject matter is an appropriate thing to do at this time in history. Editing it out, having that arrogance would be wrong. In this way, we decided to include not only the images that were race-based, gender-based, or political in those terms, we also have images that are difficult in terms of child labor, the grotesque massacring of Native culture, the egregious marginalization of gay and transgendered communities of Kentucky. We didn’t just isolate one atrocity. We took everything across all of the archives to construct that mirror like a mosaic.

AUSTIN: In a way we are creating a portrait of America or a portrait of the cities we’ve visited in the same way as the mirror. There’s something about the human condition. There’s a part about human beings in keeping other people down. And I’m not saying it’s right, but it’s a shared experience. But I think that you get attached to your own version of that experience. You know? People get attached to their own story or their own history. This is really hard to talk about. I don’t think I’m ready to put that into words.

CAMERON: Thanks for trying because I think that there’s something to me about the work that is really challenging and profoundly beautiful. I think there’s something that happens with both the planting work and the object-based work that gets at this founding question of Fallen Fruit: What is opposition? Or what is generosity? Even what is history?

DAVID: Literally. Like what is history? That is the thing that I find Austin and I not formally articulating just yet, but we’re having conversations about meaning, shifting meaning, and creating spaces for meaning to have a moment to breathe. I mean that’s what these spaces are doing if they perform themselves correctly. We’re giving everyone a fucking break. Like, it’s ok to not know the answer. I don’t know the answer. We’re creating a work of art that is a question in itself and suspends what you think you already know for a minute. It’s temporary. For a minute, it’s ok to not know the answer. It’s a relief.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.