Evading Capture: TikToks and Zines as Postmodernist Genres

For the past few years, I’ve taught a zine-making unit in my introductory rhetoric and composition course. Using the classroom as a space to promote my not-so-secret print media agenda[1], I’ve watched students puzzle over the ethics and function of self-publication. Inevitably, students direct their attention to other communication methods in popular culture, namely the role of social media in knowledge production and circulation. They’re right to look to platforms like TikTok for the grassroots utopian discourse that formerly existed only in print media—as evidenced by its role in galvanizing users to join the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, circulating COVID-19 education and recent calls for ceasefire in Palestine. Seeing various cohorts of students highlight connections between DIY self-publication methods like zines, digital infographics and TikToks has inspired me to look closer at the relationship between these forms. I am struck by how TikTok and zine communities in particular foment parasocial intimacies that take on a postmodern sensibility; sensibilities which, in turn, create more space for transgressive and activist interventions.

In many ways, zines are the analog TikTok. Even though zines have a longstanding countercultural history, TikTokers have developed their own aesthetics and signals that reflect zine ethics. Although many zines have an activist slant, all zines have an ethics of self-authorial integrity promoted by the medium. I recognize that a comparison between zines and Tiktok is not smooth or bilateral, but the formal, functional, and affective overlaps drive the recent rise of zine culture in established online cultures. Zines and TikToks seek to abstract the familiar through endless mimesis. Zines famously employ copy machines and collaging tactics to create and reproduce their bold style; TikToks’ “duet” function allows creators to add onto previous videos, or use popular soundbites to lipsync. Independent creators working in either genre collect and repurpose cultural referents in typical postmodernist fashion.

Postmodernist conventions are defined by their instability and transgression—a parodic, self-conscious palimpsest of culture, refracting its conditions as it (re)invents itself. I think of Michel Foucault’s famous quote on transgressive art: “Perhaps [transgression] is like a flash of lightning in the night which, from the beginning of time, gives a dense and black intensity to the night it denies, which lights up the night from the inside, from top to bottom, yet owes to the dark the stark clarity of its manifestation, its harrowing and poised singularity.”[2] Transgressive work will reveal the surrounding conditions, define a boundary while simultaneously crossing it and erasing it. These qualities are inherent to the genre of zines, but are perhaps less obvious in TikToks. It is true that TikToks have a clear boundary—they are defined by their being on the platform[3]. Yet, the nature of TikTok creation and culture has similar features to zines. Through the use of sound, “duet”ing, fads, filters, and the like, TikToks are a blend of pastiche and bricolage that reveal and critique social complexities as they set their own cultural standard. It should be noted that these transgressive moves are not always progressive, but their potential to destabilize creates enough of a rupture for critical discourse to permeate. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that “[postmodernism] can be described as a set of critical, strategic and rhetorical practices employing concepts such as difference, repetition, the trace, the simulacrum, and hyperreality to destabilize other concepts such as presence, identity, historical progress, epistemic certainty, and the univocity of meaning.”[4] In other words, postmodern (art)work reproduces and bastardizes the symbols of society so they may take on a new subversive meaning that de-familiarizes the conditions of hegemony. Depending on the goals of the creator and the reception of the audience, postmodern strategies can undermine hegemony and promote critique.

Parasocial Homies: Insurgent Discourse Communities

Interestingly, within these two generic camps so unequivocally focused on deconstructing and repurposing cultural artifacts, there have arisen strong legions of subgroups—people dedicated to circulating discourse about their shared interests. Content creators and zine makers both set cultural standards, many of which are contingent on diverging from a norm, and then must continue to adapt to keep viewer interest. Subgroups are defined by their niche—which is its own departure from “normativity” —to continue dis-identifying with the mechanics of their own cultural standard. Fads are fast-paced and constantly evolving as creators push the boundaries of content and aesthetics to maintain viewership. This occurrence is more immediately obvious in TikToks—a credit to the digital archive and to the millions of users—but carries truth in zine cultures as well. Zines were a cornerstone of the punk movement—a larger postmodernist wave of subversive aesthetics and a big “fuck you” to mainstream culture.

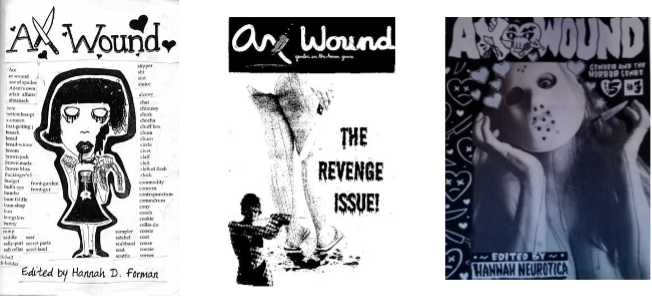

Covers for Ax Wound issues 1-3. Images captured on axwoundzine.com by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine

For example, Ax Wound, a feminist horror zine, had a run of educational sources that are now darling collectibles in zine circles. Their issues progressively pushed their own aesthetic boundaries. These compositional shifts serve the practical purpose of exciting interest through novel design, but they also continually reassert their punk allegiance by refusing to codify a singular or authoritative style. Instead the style changes as its participants and their interests do, showing a community in continually divergent dialogue. Ax Wound’s “About” page describes its goal to push against patriarchal values in the horror genre and open up a space for “feminist horror fans of all backgrounds to discuss the themes of gender, sexuality, and culture in the genre both past and present.” Evidence of this discussion is right next to this mission statement, in the form of rotating quotes from horror industry workers and horror fans who praise the zine and its editor, Hannah Neurotica, for facilitating a bold, intelligent approach to horror film criticism. Both the aesthetics of Ax Wound’s art and the content of its reviews and essays evolve through an iterative process that foregrounds the constant cross-influences of a community dedicated to making a place for women in horror.

The shared parasociality and activist ethics of some TikTok and zine subcultures goes beyond their generic conventions.[5] For one, these communities are typically associated with youth[6] as seen by the overwhelming presence of Gen Z at the helm of either genre. Both genres also rely on the creativity of the content creator and the choice of viewer to opt-in to the discourse. And with the (albeit problematic) function of algorithms in spreading content, grassroots discourses are propagating farther and faster than ever before. The approachability, self-authorship, and self-publication of zines is simulated by TikTok on a much larger scale. That said, creators on TikTok are explicitly aware of how algorithms are predatory with the content they promote and who can see the content once it’s published, creating tension between the goals of the creator and outcomes of these platforms (i.e. trading in some of the goals of social justice at the price of surveillance and censorship). But the power of print media reintroduces zines as a method of circulating knowledge, plans for demonstrations, and other solidarity work with discretion. See this video by the official Dr. Marten TikTok page. Here, the speaker, Rudy, opens the video by asking “how do you share information that society wants to silence? You make a zine.” Claiming that Dr. Marten has always stood for self-expression, Rudy connects the brand to the use of zines for education and advocacy in LGBTQ+ spaces. Once the bat symbol for punks, Dr. Marten still holds plenty of sway over counter-culture. It comes as little surprise, then, to see them promoting the use of zines for activist organizing. The brand isn’t taking a clear political stance here, but they are signaling, if not outright encouraging their customers to engage in insurgent discourse. As my colleague Rose Steptoe observes, it’s likelier that the multi-billion dollar company is only seeking to capitalize on the association between punk culture and zines, but reaching for zines to authenticate their punk allegiance is telling of zines’ reputation as a subversive medium. Zines, especially among this new generation of zinesters, combines the postmodernist appeal of communication platforms with the (para)social effects of activist organizing. I am interested youth’s ongoing and evolving connection to postmodernist genres, primarily the connection between TikTok and zines, how they compare, and how TikTok is helping promote zine culture.

Zines were a favorite among counterculture organizers in the 90s, as they provided a low-cost self-publishing opportunity. Riot Grrrl famously popularized zines for that purpose, spreading feminist paraphernalia across and through subcultures. And while they’ve never disappeared, zines certainly went out of vogue in the late 2000s, except for a few artists who kept the tradition alive through zine fairs. But zines are regaining popularity! The Brooklyn Museum recently ran an exhibition titled “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines” (from November 2023-March 2024) presenting a comprehensive look at the co-evolution between zine culture and various subcultures since the 1970s. Press covering the exhibition has noted the current rise of zine culture (see Gothamist, Smithsonian Magazine. One short thinkpiece in UC Irvine’s campus newspaper claims that Gen Z is drawn to this form of knowledge circulation (New University). I venture that youth’s proclivity for subversiveness makes transgressive forms more appealing—not to mention, both zines and TikTok offer low-cost creative outlets and community.

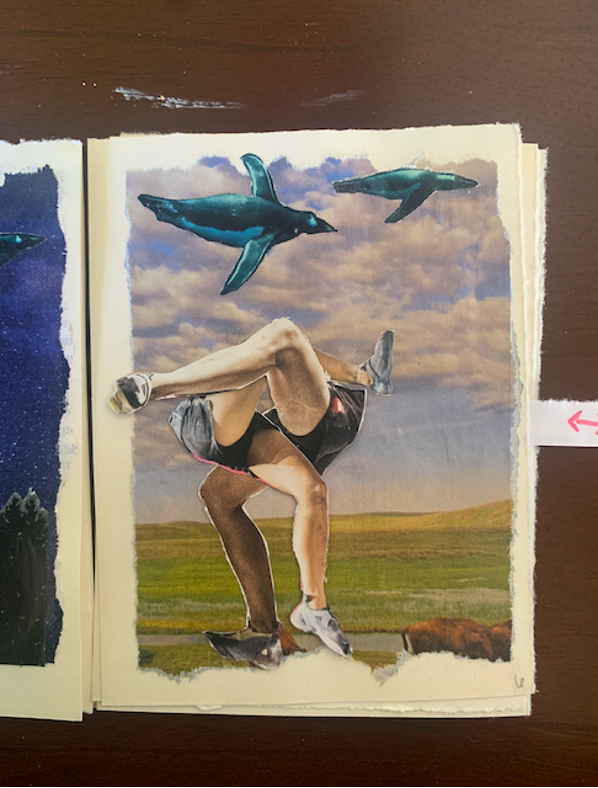

(Figure 1: Page from “But BRO eye feel so very Gay Ooey Gooey obsessed with 4 you” by Ryan Luedecke)

Zines and TikToks both contain a dubious physicality and ephemerality that promote closeness. In their impermanence, difficulty to source, and affective traces, both genres approximate intimacy, however fleeting. TikTok’s boundless “For You Page” (FYP) assures content’s relatability. Videos not liked or saved, however, are almost impossible to find once the page refreshes. My frequently-visited hell looks like this: my friend and I are laying across a couch, one or both of us references a video we saw on the internet—“oh, I have to show you this TikTok I saw,”—only to search endlessly and never locate the video again. But the beauty of wanting to share a video is not lost on me. Students have sent me TikToks, or referenced videos in class, surprised to learn that I am in on the joke. I am in on the joke, and I’m in on the discourse. A proud member of various subgroups, each with a compound name like “zinetok,” or “booktok,” I find community with likeminded users. TikTok creates familiarity on the platform and off, elsewhere studied in detail.[7] Some creators have begun to satirize this phenomenon, calling chronic users the “brain rot friend.” See this video by @mustafaa&izzy. The screen reads “Just two besties with stage 3 brain rot.” As the shaky phone camera tracks one creator at a time, they quote other popular TikToks, generating, as it parodies, an endless self-referential loop, a postmodern phenomenon that Jean Baudrillard would refer to as hyperreal. In Symbolic Exchange and Death, Baudrillard argues that ideological apparatuses that structure society are simulations.[8] The real and the imaginary are subsumed by symbolic referents, so much so that there is no longer a connection to reality. The “brain rot friend,” is a comical way of highlighting the metasimulation of internet culture while paradoxically finding connection with content creators in a digital reality. Anyone who has ever tried to create a TikTok has also likely experienced the immense frustration of using the incredibly un-intuitive in-app features. Videos on the platform thus create proximity through the content on the page and through traces of the creator in the video itself, as seen with the shaky camera work in @mustafaa&izzy’s video.

Zines, of course, also engineer affective proximity. Alison Piepmeier argues that part of the zine form is its textual body, which promotes intimacy with the reader. “Layers of meaning” Piepmeier writes, “become visible when we move beyond the written word to the artifact itself.”[9] Zine communities are united by the confessional content as much as by the physical production of the artifact. For example, a one-off zine titled “But BRO eye feel so very Gay Ooey Gooey obsessed with 4 you” by a local creator showcases two sets of legs that readers can move in an interlocking stance (Figure 1). The tedious task of collaging every word and image in the zine, and making some of the elements mechanical has immense affective resonances with the reader. I feel an affinity with the creator, not only because of the scissoring figures, but because of the thoughtfulness and intentionality they demonstrated in the physical construction of the book. Shifting the figures requires readers to engage carefully with the textual body, creating a feeling of intimacy with the zine and, by extension, it’s creator.

But how can a social media platform —the media embezzler of the future, credited with our fears of print obsolescence—find any bond with slow print media? The affinities cultivated through these mediums might seem contradictory, but speaks to their shared postmodernist appeal. Since the advent of the digital archive, publishers and humanists alike have argued over the incompatibility of these forms, treating digital media with significant apprehension. Social scientists are now also directing concerns to how online connection impacts socialization. Recent scholarship has focused on TikTok supremacy as a culvert to other forms of connection, on or offline. İrem Şot’s 2022 study rightly points out that social media companies eschew transparency by emphasizing the community-building capacities online, saying they “rendered invisible the extent to which these platforms have monetized their users’ attention and data through algorithms and software, transforming our natural sociality into ‘platformed sociality,’”[10] but I wonder how much of our “natural sociality” has been produced without a “platform.”[11] Communication is constituted by its vehicle, i.e. the formal and generic qualities of its medium. Although we need to be critical of technological advancements and their effects on society and socialization, there is room for social media and print media to exist alongside each other, and perhaps even complement each other.

The persistence of zine culture is ironically partially through TikTok. Take, for instance, the existence of “zinetok,” a conglomeration of zinesters on tiktok sharing resources, guides, and how-to’s. One of my favorite “zinetokers” is @brattyxbre whose videos on how to make zines and zine designs have garnered as much as 2 million views. Her zines are true to the DIY form, playful, creative, and at times, confessional. Her most popular videos describe the content in her work or show how she generates ideas for her craft, including picking adjectives and nouns out of a beanie. Other content creators like @kathrynbrammall have become popular for their illustrative style and instructive videos. In fact, that seems to be a trend across zinetok—the most popular videos are consistently demonstrations on how to make zines, but these videos, like this one by @antagonist about an essay they converted into a zine, have pretty minimal viewership. In the TikTok, we see a low-angle POV of the user hand-cutting individual lines from their essay and images to paste into their zine about Chicanx fashion and racialization in media. The zine features multi-page spreads with images in black and white and in color. Hand-drawn elements outline the images and borders of each page. It’s beautiful. Somehow, @antagonist’s video only has a little over 2000 views, and the follow-up video showing the completed project has even less. Why do critical pieces seemingly garner less attention? Especially when they are as focused on aesthetics as their more viewed counterparts? Social scientist Safiya U. Noble argues that these trends are reflective of a form of “technological redlining” as a result of racist and sexist algorithms.

“Corporate-controlled governments and companies,” Noble writes, “subvert our ability to intervene in these practices” of algorithmic oppression.”[12] But TikTok has always been different. Since its departure from the Musical.ly model, users have been critical of its algorithm. Thinkpieces like this one from The Hill argue that “TikTok is China’s Trojan Horse.” The Guardian similarly published a piece titled “TikTok is Part of China’s Cognitive Warfare Campaign,”and folks like Sen. Marco Rubio have called for the demonetization of TikTok until China hands over their algorithm (CNBC). Congress has long debated banning the app nationwide, and now have focused their attention on college campuses—emphasizing the connection between youth and threatening discourse platforms. TikTok’s owners indeed mine and sell data with unclear objectives, but there is no current evidence that the Chinese government uses the app to “spy” on users and sell their personal data to foreign adversaries. When the Trump administration first issued a threat against the app, many users railed against the president, chiding his aversion to critical dialogue. I still wonder if the fear of the app has less to do with metadata and more to do with the volume and rapidity of TikToks.

While the TikTok algorithm is at once scapegoated as the site of the modern Red Scare, it is equally embraced by users seeking community through the highly curated “For You Page.” The highly individualized selection of videos can have an “echo-chamber” effect, but can also connect and educate users. For example, @DylanMulvaney rose to popularity in 2022 with her “Day of Girlhood,” series, which demystified her transition, offered education, representation, and support for some trans viewers. Mulvaney now boasts 10.2 million followers on TikTok and has partnered with major corporations like BudLight and Nike. Regardless of any subsequent controversy, we can acknowledge the role the platform has had in making conversations around things like gender less opaque. She and plenty of other users have also used their videos to ask for user support “getting them off the wrong side of TikTok.” See, for example, this video by @jordallenhall asking for viewers to share within progressive circles to save them from getting more hate online. Jordan is a self-identified “fat, trans-masc, disabled activist and model.” They specifically ask that viewers who are “fat positive, trans inclusive, or disability justice aligned” to interact with the video. In other words, while algorithmic oppression is at-play here, many users on TikTok are acutely aware of it, and, at times, use it to their advantage. Fear-mongering social media ignores the agency and resilience of its users.

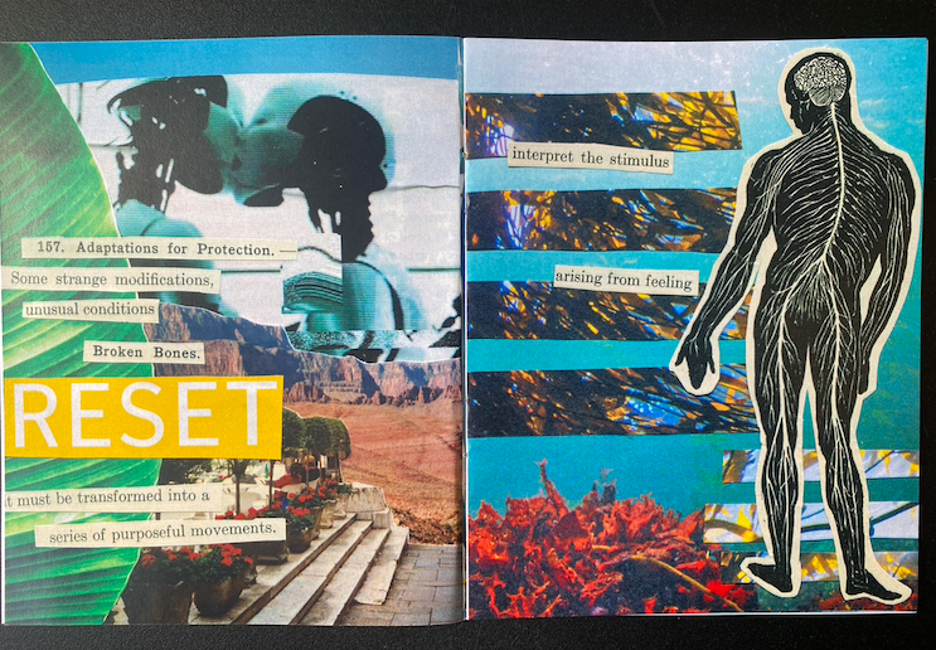

(Figure 2: Page from “Dangerous” published by the Zine Bean Collective)

You Can’t Catch Me: Genre Evading Capture

It’s true that we need to be wary of the restrictive practices of codes that mediate our online socializing, but users have found loopholes to creating the kind of discourse in which they want to engage. It is the recalcitrance of content creators that gives their work a postmodernist appeal. Adaptation and working within limited materials are clear political techniques, and they are inherent to zine culture, hence their popularity for political projects. My friends at Zine Bean Collective captured it beautifully in their bricolage poem seen in Figure 2 which reads “Adaptations for protection […] must be transformed into a series of purposeful movements.” Artists working in postmodern genres, especially with activist aspirations, must continually alter their message to evade to limiting capture of hegemony. Continuing the tradition of adaptation and ingenuity, TikTok users are adept at studying the patterns of the algorithm (its own hegemony) and using the mechanisms of restriction as a boon for their message. For example, when users realized that videos about Palestine were being silenced, many started using watermelon iconography, hashtagging #P@lestine to evade language recognition software. Likewise, closed captioning on videos has been adapted to escape the scrutinizing authority of the algorithm. Often, creators modify the speech bubbles to say or spell something different than what they actually say. These tactics undermine the command of “technological redlining” to circulate dissident content. So while these short-form videos are public data, and meant to be treated as such, they engage in a system of clandestine signaling and insurgent discourse. And because zines are typically self- or independently-published, they too evade censorship and surveillance tactics. Part of this surveillance-dodging is the gaze of genre.

Zines evade clear categorization. When I teach my zine unit, I always ask “what is a zine? What makes a zine a ‘zine’?” Students are always confused. Even after we attend a library session to look over the university’s special collection, students leave more confused than when we entered. “Is it just that it calls itself a zine?” a student asked me once, clearly irked. “Absolutely!” How else do we find connections between 3×5 inch booklets made using only a scanner and the behemoth “Boys Don’t Cry” zine created and distributed by musician Frank Ocean during his Blonde tour? Even worse, how do we tell folks like Alison Piepmeier that the textual body, so central to the cultivation of intimacy in zines, is being subbed out for other digital platforms as e-zines gain popularity? Daniel C. Brouwer and Adela C. Licona argue that digitized zines serve the important purpose of increasing accessibility and preserving the material.[13] And while they conclude that digitized zines aren’t zines at all because digital forms cannot approximate the architectural features of print media, they also conclude that trans(affective) mediation helps us understand that even if digital zines do not faithfully reproduce the experience of a print zine, they do produce a distinct and valuable affective connection. It’s true, I cannot imagine how I would create an appropriate digital rendering Luedecke’s mechanical scissoring legs, or the delight of manually moving them back and forth. But I also cannot imagine the print version of any e-zine. An endless portal of original creation and cultural detritus, websites are something different. It is interactive, but it isn’t a game. It’s not a blog. There is no name for it in our lexicon, and I would be out of line to produce a new nomenclature when the artist has already done so. If it is true that “what makes a zine a zine is that it calls itself a zine,” then we must trust the creator when they say they’ve made a zine. Limiting the category of zine to print material neuters the purpose and possibility of zines as an ever-evolving postmodernist genre.

Concluding Thoughts

Much to the delight of corporations and the chagrin of progressives, the popularity of the TikTok shop has transformed the platform. Discourses previously circulated about online attention economies are now made more lucid by the literal connection between attention and advertising, termed “platform capitalism.” TikTok users can now link items mentioned in their videos to their “shop” and make a direct profit from the products sold there. More egregiously, creators don’t even need to link to their personal “shops” for TikTok to detect products in their video and advertise similar items in the shop. I worry that the cooperative and utopian potential of TikTok is being neutered in real-time and impacting some of the other genres here discussed. Individual content-creators are using the TikTok shop to promote and sell their zines, and I am glad to see artists have another accessible space to sell their work, like @tannerfrostbowen seen promoting their educational zine “How to Develop a Sewing Brain” here, which retails for $15. I can’t help but stop and think of critical zinesters like my buddy who tables anarchist zines around town under the pseudonym Long Leaf Distro, hand-printed from their own computer using their own resources and handed out for free. Profitability will always cause moral quagmires, but does that take away from the postmodern affect these genres have on their users? In their recent manifesto, Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell writes “Through the digital, we make new world and dare modify our own”[14]. Used together, digital and print media diversify tactics for insurgent discourse, pushing the boundaries of their own creation and creating more space for evaluative reflection on the conditions of society. The postmodern world is more human-manufactured than natural, iteratively creating more distance between artifacts and their referents, and material from its source. Zines have survived through multiple generations of digitization, and, in fact, are promoted through digital social media platforms. Combining the longevity of one genre with the rapidity and rebelliousness of another can help us negotiate the conditions of a postmodern world and create platforms more readily suited for activist projects. I don’t think TikTok is the best or even a good example of a cooperative platform for activist work, but I do think that it has demonstrated how internet publics can transform and even evade social constructions. From this, we can follow Russell’s call to create a new (digital) world that mediates the ethics of insurgent discourse.

[1] Zines are canonically difficult to categorize, but they tend to be independently produced media that invite reader collaboration—while there are plenty of online zines, I am specifically focusing on print zines here.

[2] Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews (Cornell University Press, 1977), 35.

[3] Although one could certainly argue that all works are defined and limited by their platform.

[4] Gary Aylesworth, “Postmodernism,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Last modified February, 2015. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=postmodernism

[5] Kristin G. Congdon and Doug Blandy, “Zinesters in the Classroom: Using Zine to Teach About Postmodernism and the Communication of Ideas” Art Education, vol. 56, no. 3, 44-52.

[6] James Amberson, “The Age of the Maturing Zinester: aging zine makers are taking a medium traditionally associated with youth cultures and making it work with their adult lives.” Broken Pencil, no. 62 (2014). Gale Literature Resource Center (accessed March 21, 2024). https://link-gale-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/apps/doc/A365736646/LitRC?u=unc_main&sid=summon&xid=c58a1176.

[7] İrem Şot “Fostering Intimacy on TikTok: A Platform that ‘listens’ and ‘creates a safe space,’” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 44, no. 8 (2022): 1490-1507.

[8] Jean Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1993).

[9]Alison Piepmeier “Why Zines Matter: Materiality and the Creation of Embodied Community” American Periodicals, vol. 18, no. 2 (2008): 214.

[10] Śot “Fostering Intimacy on TikTok,” 1493.

[11] I use the term platform here to refer to genre. That said, the term “platform” is fraught in media studies. Folks like Nick Srnicek have argued that platforms are their own economy which reiterate the structure of capitalism in the digital sphere. Scholars like Trebor Scholz argue for platform cooperativism, promoting a decentralized platform economy, and still others find that proposition inadequate to contend with the capitalist model. Before the advent and popularity of the “TikTok shop,” the platform avoided the capitalist designation that now dominates the digital sphere. Intellect and creativity were, until recently, not directly commodified through TikTok. As we parse through the relationship between genre and platform, it’s useful to consider the role and decisions of the creator in choosing an appropriate genre/platform for their message.

[12] Safiya U. Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

[13] Daniel C. Brouwer and Adela C. Licona, “Trans(affective)mediation: Feeling Our Way From Paper to Digitized Zines and Back Again,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 2016, vol. 33, no. 1, 70-83.

[14] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifest (New York: Verso, 2020), 11.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.