Contradiction Study

“…the uneasiness of being a subject torn between two languages, one expressive, the other critical; and at the heart of this critical language, between several discourses, those of sociology, of semiology, and of psychoanalysis—but that, by ultimate dissatisfaction with all of them, I was bearing witness to the only sure thing that was in me (however naïve it might be): a desperate resistance to any reductive system.” —Roland Barthes (trans. Richard Howard), Camera Lucida

“The archive, it must be noted, is also your enabling fiction: it is the thing you say you are doing well before you are actually doing it, and well before you understand what the stakes are of gathering and interpreting it.” —Julietta Singh, No Archive Will Restore You

“When the Young-Girl has exhausted all artifice, there is one final artifice left for her: the renunciation of artifice. But this last one really is the final one.” —Tiqqun (trans. Ariana Reines), Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl[1]

First I photograph the photographs, then I write six or seven versions of the sentence I photograph the photographs while it’s raining. I put it in different tenses: present, like I’m being a literary critic (a field in which the ‘historical present’ is often used, which confuses me even when it also makes sense), or past, like I’m telling you a story. Future? When I’m taking the photographs, in the spring of 2011, it is somehow already true that I will be photographing the photographs while it is raining in 2024. Clocks don’t kill time, they try to measure it, which is equally impossible and twice as bewildering. Photographs do and don’t pin moments down. I read about infinity like this could tell me how to live, which only sometimes works.

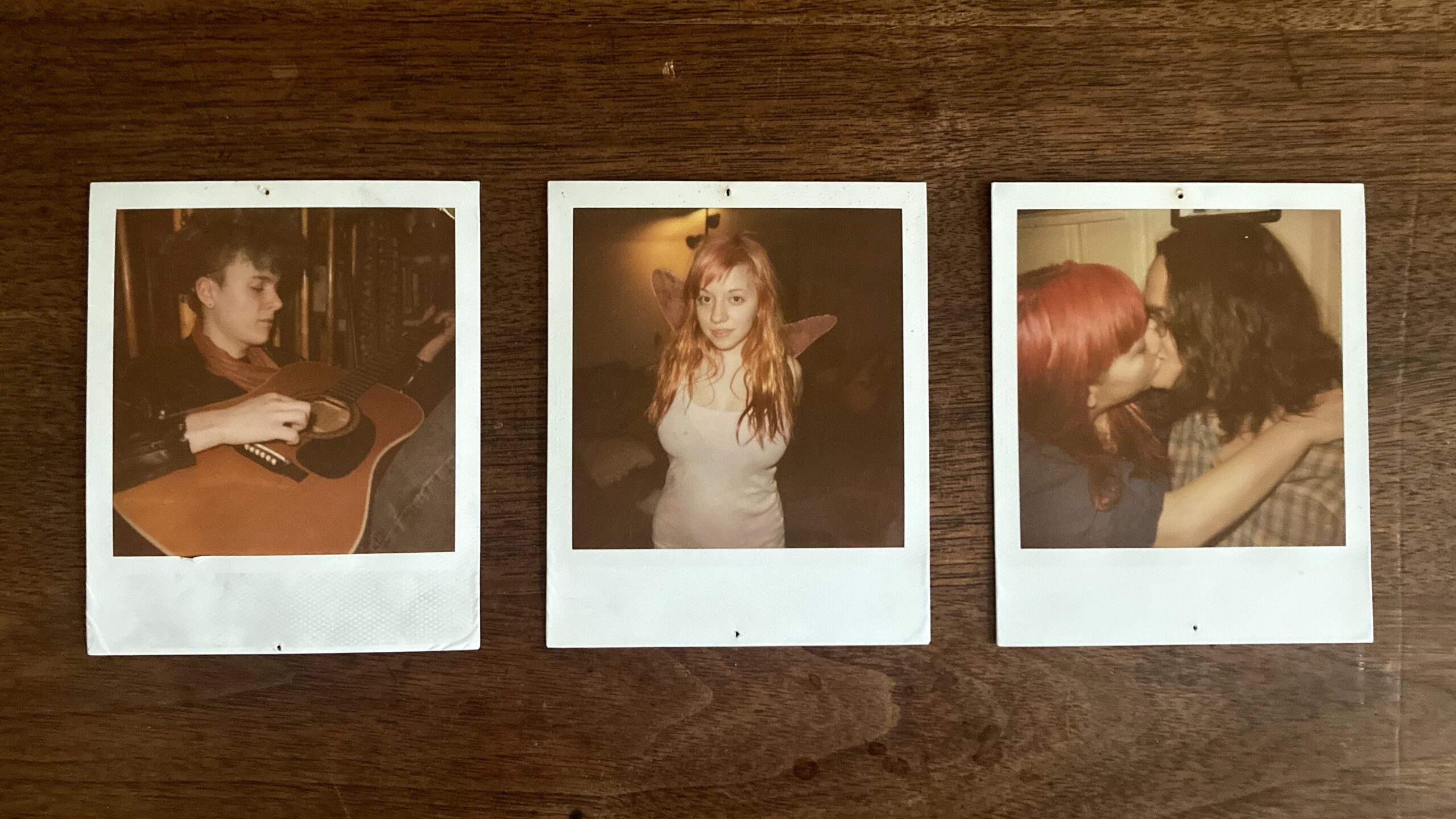

I photograph the photographs to write about them. I am stalking my own soul writes Amina Cain in a book about art and life and the overlap between them.[2] I am trying to give an account of a self I no longer am, a seventeen-year-old Ohio teenager with a scholarship to private high school, a Tumblr account, and a Fuji Instax, wide-format.[3] That self was—let’s go with the historical-present thing, is—an only child. Lonely, though she has friends, a boyfriend. Smart enough that she downplays it to seem more normal (failed project, in most ways), but also doesn’t know how to work hard on anything; writes all her papers in the middle of the night. Takes pictures that look like this:

There’s a bit of a Coppola/Eugenides reference coming through in that left-hand frame, which scans.[4] I read and watched The Virgin Suicides when I was young enough to think that that scene of Lux fucking some random man on the roof was beautiful, aspirational, instead of kind-of-dehumanizing—of course it’s both.[5] As I recall, Lux was one of the more sexually liberated young women I encountered in my reading pursuits, which were various, lively, and subject mostly to the selection of the nearest branch of my local public library.

As for the dress on the bed, I remember taking that picture well. It was dusk, and the light in my attic bedroom (Cape Cod suburban house with the half second-story) didn’t translate to film the way I wanted it to. It was my prom dress. I bought it for five dollars at Valley Thrift on Woodman Avenue, in Dayton, Ohio, which is still there and remains a truly top-notch thrift store, pilgrimage-worthy. It was floor-length; likely someone’s bridesmaid’s dress. It fit me well enough and was designed such that I didn’t have to wear a bra underneath, which pleased me. My mother hemmed it on the sewing machine she’d learned to use when I was small. We were practicing our femininity. Here, look how accurate my performance of teenage girl could be:

When I am photographing the photographs, the same instinct kicks in that does when I’m editing a paragraph, my own or someone else’s: an intuitive sense of arrangement that I can’t quite explain. The photograph of the Matroyshka dolls lined up on my bedroom windowsill belongs next to the photograph of my boyfriend (we’ll go with L, here, though that is his middle initial), me, his twin brother (H), and his twin brother’s (platonic) date (R) all standing outside on the lawn of my house. This has to do with visual principles that I learned, young, but couldn’t explain in language for you if I tried.[6] It has to do with lines and also has to do with subjects. I can’t think of the stacking selves nested into each other without thinking of human-selves-across-time, and I can’t think of this young self of mine from any other subject position than my own, now, and I can’t look at this right-hand photograph without my heart hurting (I would eventually marry that boyfriend-now-ex-husband, and am writing this, now, less than a year out from our separation; we still need to deal with the paperwork that legally enacts the “not being married anymore” thing). My favorite thing about it, though, is the fact that none of us are looking at the camera; clearly two pictures were being taken at the same time, one of them with the Fuji Instax, one likely with a digital camera. Probably not a phone. Technology changes almost as quickly as we do, or more quickly, depending on what rubric of “change” one is using. I don’t know what one I am.

More quickly is also the way I’ve jumped into these sentences. I should explain myself, slow down a little. Do you want to know more about us? Here—

It would have been me who took the left-hand photograph of H playing the guitar—that’s my room he’s sitting in; my mother’s old Alvarez on which he’s probably playing “Blake Says” or maybe “Fake Palindromes” or maybe even, appropriately-enough, “Fluorescent Adolescent”—and probably H who took the photo of L and I kissing at what I think might be Dino’s coffee shop in Yellow Springs, which is still there, though they may have remodeled, and either one of them could have been the one to take that middle photograph of me in my fairy-wings, pink hair fading out, leaning into Manic Pixie Dream Girl and wearing my formative reference points on my sleeve.[7]

I should explain, too, that I am trying to think about probably seventeen things at the same time, but what I am trying most to interrogate are two things specifically: gender performance and nostalgia/aesthetics. And more importantly I am trying to figure out why for me personally, those aren’t different things.

I have pointed out already my own performance of the gender/trope called teenage girl; perhaps now is the moment to share also that I have lately been using the word girl less for myself and sometimes using the word nonbinary more, although I do not love this latter word (like “nonfiction,” it suffers for existing only in contradiction to something else) particularly. But “I reject the terms of your argument” is a little wordy to be effective as a gender marker in normal conversations. “Nonbinary” is good enough, and describes me accurately-enough, and I would like to hazard even that it also describes that kid in the middle picture, who was also a girl, and very worried about what it meant to be a girl and how to be a girl and whether she was doing it right, which I think most girls worry about, even the ones who have always been understood to be girls (cis girls) who have girl-ing pretty easy in many ways, comparatively speaking.

My sentences get so unwieldy as soon as I try to talk about anything that really matters. I used to edit this away obsessively, writing and rewriting until I sounded like I actually believed that I knew what I was talking about. These days the only thing that feels like a viable ethics (a good-enough politics) is to say when I know what I don’t yet know, and I don’t yet quite know how I think about gender, my own or more-broadly. But I know some of it. I know this pink-pastel-monochrome fairy-wings seventeen-year-old in the picture is both a teenage girl and a nonbinary child and that for me personally there is no contradiction, there, though nonbinary people mean different things when they use the word “nonbinary” and for some this means the binary gender they were assigned at birth is not correct, has always been wrong, and for some, like me, it means something else. Something like “both things are true in different ways,” which is of course both too easy and usually how things work.

Maybe I can say that more clearly: I feel no particular dysphoria or vexed-ness around my corporeal embodiment situation, and for the longest time I thought that meant that whatever gender ambiguity kept surfacing in my thinking didn’t count, wasn’t real, that I’d be taking space away from some other, real nonbinary person if I said it. I don’t think this anymore. I think the door to imagining oneself differently is one that anyone can open if they want to, and I keep joking that gender is a scam that hurts everyone but like most of my better jokes this is not really a joke. Saying gender hurts everyone, of course, also doesn’t erase the fact that the ways it hurts are unequally distributed, and trans people whose gender presentations differ legibly from normative expectations tend to be most subject to violence as a result of it. I have not historically had this kind of violence directed at me; this is an immense privilege, and I don’t want to speak for anyone’s human experience—nonbinary or otherwise—besides my own.

Some days even speaking for my own experience seems like a bit of a stretch, but I think this is the wrong kind of hesitation entirely, and I’m working on that. I know, too, that it matters to say this out loud, to think through some of one’s own I don’t know yets in public because trans and queer and nonbinary kids are still dying and so many people want different, freer ways to think about their own human selves, and I think I know that thinking freely and expansively about oneself is a human right. It is also a human right that is very difficult to think about when other and more basic human rights are not being met (food, water, not being bombed).[8] Tranquilize me with your ideal world sings Girlpool, who I didn’t start listening to until college but who describe my own teenage experience fairly accurately.

This got heady. Here is another pair of pretty pictures.

On the left: a field probably off to the side of Dayton-Yellow Springs road, which I spent a lot of time driving or being-passenger on, back and forth from school and L and H’s family’s house, in which some of them still live. On the right: my best friend at the time, B, in what appears to be her neighborhood. This must be February or March, early spring, not long after I acquired the Instax camera (the square Polaroids, above, were from a camera that had been around since my childhood; it still had some film in it, and then I may have bought a pack of Impossible film too—but Impossible film was expensive; the Fuji product was and is more affordable, though I admit that I prefer the squares).

Here is a small but noteworthy thing: on that left-hand picture, you can see both then-me reflected in the passenger rearview and now-me reflected in the glossy surface of the photograph. Time is material. Ideally, these sentences would be voiced by all of us at once: my current self and that past self and preferably all of the selves in-between us. But it would be incoherent. It would sound like the kind of music L is into sometimes but that I generally can’t stand to listen to. Not necessarily because I don’t find it meaningful. But because it’s too much.

I love that picture of B, who I photographed often and who was, and is, beautiful. She has a baby now. That doesn’t seem real, either.

I know, because I wrote it down on the back of the image, that the left of the pictures that follow was the first one I took on the Instax camera after I bought (or was given; can’t remember) it:

You will have to take it on faith (do I seem like a reliable narrator?) that as soon as that first Instax picture faded into existence out of primordial chemical thisness I had an uncanny feeling that I was looking at it from very far away in time and telling some imaginary, curious interlocutor, of the girl on the left with the long auburn hair, that’s her. That’s S, who was the first girl I ever loved, to whom I once said maybe I’m just straight after half a year of off-and-on kissing etcetera, which I regretted saying for the better part of a decade until we started talking again and some of the guilt wore off. I don’t think either of us ever changed our Facebook relationship statuses to it’s complicated that year, but it would have been accurate. I sometimes describe that last year of high school as failed first attempt at consensual nonmonogamy, which is accurate, too (“first failed attempt” would, for that matter, also be accurate), and is another story. But it’s enough to say I loved her in a way I struggled to understand, and that this was in some sense mutual but that neither of us knew quite who we were or wanted to be or how we wanted to structure our relationships, which I think is fairly common.

I’m speaking about this as though from rather far away, as though twelve years were long enough to have outgrown the feeling, for whatever spark (whatever sparkle) to have thoroughly worn off, but I feel approximately the same way looking at that photograph that I did the first time I looked at it: like the truest thing I could say would simply be that’s her.

So—that’s her. And that’s him, on the right: not my lover but his twin (fraternal), who before he was my boyfriend’s brother, before he was for a time my brother-in-law, was my first queer family: before I’d ever heard that phrase, before I knew that that was something I would ever want or need. I’m lucky because I already had it. He (H) and I became friends in freshman year when I showed up to school one morning having cut my own hair in the bathroom the night before with kitchen scissors, cropped to a haphazard pixie-ish chin-length. H told me I looked like Liza Minelli; I, less-cultured by a long shot, didn’t catch the reference, but sensed enough to take this for the compliment it was. Though he’d dated girls in the early days of high school, I think H’s queerness was legible to me in the same way mine may have been legible to him: in some unstated way, like sonar. Then again, mine may have been invisible, impossible to read, for the same reasons it was impossible for me myself to read it.

Maybe understanding what hasn’t been said aloud, or what can’t, is one of the conditions of queer friendship, or even of friendship itself.

The left of these photographs of my high-school grad party has always given me the impression of a scene from a Virginia Woolf novel, who wasn’t yet my favorite author when I snapped the photo but who I first read because L’s mother—one of L’s mothers—D (second from the right)’s favorite book is To the Lighthouse, which is my favorite book now if I had to choose just one, and has been for some time.[9]

As for the right-hand image, it was my favorite of L and I for a long, long time. I think now that the reasons we married and the reasons our marriage failed[10] are both legible in it. It is beautiful to hold each other this tightly, but very difficult to know—especially when young—when one is also using this holding (this holding-on) as a way to avoid independence, or even to avoid the pain of having to define oneself or inhabit one’s own chaotic and various and singular subjectivity. (One’s own wild, precious, ridiculous, ineluctable self!)

But I still love the photograph. It says what we were like.

Is this my attempt to narrate my own nostalgia, or to untangle it, to find my way out of it? This is another of the things I don’t know, another both/and, another true contradiction.

I can feel myself caught between discourses again: or maybe just caught between the terms of what I call Ashbery’s Paradox when he starts Three Poems with the question of whether to leave all out or put everything in. Could I tell you the whole story, describe all the characters, make my own life—I lived it!—into a well-constructed fiction, the kind that would feel immersive, the kind that feels realer than real life? That isn’t what I’ve done, here, but I haven’t done the other thing, either—I haven’t theorized it, not really. I’m too close to this self, still, and also too far away. I don’t understand her and I know her too well. She’s me and not-me, mine own and not like one of the bewildered lovers in Shakespeare’s Midsummer says to one of the others when they’re all waking up confused about who they are and who they have and haven’t fallen for. I could make it more experimental, narrate all this from the voice of that coffee cup on the Waffle House table. I have had the sense, more than once, writing this, that the photographs themselves are the essay; that my writing about them says less than the images alone would; on the other side of that coin lives the feeling that I should leave the photographs out, that it would represent them more accurately to essay around them, to withhold them. It’s very me of me to try to have it all of the ways at the same time, to aim not for the balance point between maximalism and minimalism but somehow to convince myself they aren’t opposites and aim for both extremes.

I wonder idly what my 17-year-old self would’ve thought of this essaying, though this question is meaningless. She cannot read me. In this way our relationship is very one-sided. (I think that would’ve made her laugh, though.) If in some sense my you here is, impossibly, the self who lived these moments—if this is true in the same way she was making the images for me—is that just hall-of-mirrors narcissism or is it something realer, more durable, a way of allowing oneself to believe in time which is also willing oneself to live through it?[11] Of course I think it’s both. I quote that Barthes line I used as epigraph like this caught between discourses, this desperate resistance, could save me from having to choose. Maybe it can, does.

I want to give that younger Jo the last word here, even if this can only happen wordlessly, as an image. That’s okay. Sometimes one likes becoming a blur, fading into the plane of the reflection, pale in the light of the flash. Stilled into an ongoing now that was somehow also already a then. These were taken at my once-favorite Thai place, since-closed.

There might be something else there now.

[1] A note on these epigraphs: Barthes’s Camera Lucida (the edition I have is from Hill and Wang) remains one of the best books I’ve read on photography that is also about living and grief; Julietta Singh’s No Archive Will Restore You exists as a free (you read that right, free!) PDF or inexpensive paperback from the wonderful Punctum Books and you should read it immediately; Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl (Semiotexte) is a book that confuses me more the more I think about it, which I see as a good thing and which is (I think) part of their point, at least methodologically. I include these lines about artifice because artifice and the embrace and/or renunciation of it are part of what I am worried about here, and because I find these sentences both somehow true and bewildering.

[2] Indelicacy, FSG, 2020

[3] cerulean-salt dot tumblr dot com no longer exists, but used to, and I remain pleased about once having had this handle, titled after the Waxahatchee record, which is no longer my favorite but which I do continue to love.

[4] Sofia Coppola directed the film version of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides (1993) in 1999.

[5] I did not have a copy of the novel at hand while writing this essay, and though this sentence may live to haunt me, I think there’s something important too about the way texts and characters come to live in our minds—whether or not we’ve apprehended them accurately.

[6] Or, rather: I could, probably, but I couldn’t do it beautifully, and that would bother me enough that I’d refuse to try in the first place. In some ways, this is a failure – it is good to try to say what one means, to be willing to, even though this also means making sentences that are messy sometimes, that lack grace – but it’s also something else.

[7] I love James Frankie Thomas’s 2019 essay on “Francesca Lia Block and Nineties Nostalgia” at The Paris Review’s blog, here.

[8] I am referring mainly here to Israel’s genocide in Palestine, which is ongoing as I write this. I have no particular expertise on this matter, but this publication has offered a reading list from some past contributors who know more.

[9] Any further sentences on this matter would be hopelessly sentimental; just go to the source. I recommend especially the scene in which Lily leans her head on Mrs. Ramsay’s knee, for the bee and the tablets and everything else.

[10] Though of course this really isn’t how I think of it. Much is revealed in the ways we find ourselves making sentences we don’t mean (however hard we try to do otherwise!) as result of the available scripts.

[11] See Alice Notley’s poem “Synchronous Chronology,” in Mysteries of Small Houses, which includes the perfect phrase (addressed to a younger self) “Protect me and you’ll have a later.” I would like very much to be able to disk my teenage self a copy of this volume. Ideally it would fall off an apple tree directly onto her head. In the fantasy version of my so-called life, this totally happened.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.