Between Rival Utopias: Craft and Community in the Counterculture

The question of “clubs” is one that encompasses the tension between inclusion and exclusion. The “clubiness” of the three communities discussed here—Camphill Village Copake, Chardavogne Barn, and the Fellowship Community at Threefold—consists of their exclusion of both capitalist efficiency and aesthetic idealism. In their early years, they also formed an ambivalent conversation with (both including and excluding) the broader counterculture, serving as refuge for, exemplar to, and contrast with communities that fit more neatly into the counterculture stereotype of “hippie communes.” In a correspondence between author and curator Erin Elder and Roberta Price, a photographer and former resident of Libre, a commune in Southern Colorado, the latter observed that, “The counterculture occupies a historical niche somewhere between a pernicious social virus and an amusing Halloween costume.”[1] Since the counterculture began to be historicized, the public discourse surrounding it has careened between these two poles—fear of its challenges to social hierarchies and systems of power, on the one hand, and on the other, contempt for its seeming absurdity and frivolity. As Elder’s and Price’s conversation attests, one of the places where we can see these contradictory responses in full flower is in the reaction to intentional communities (sometimes inaccurately generalized as communes). The spectacle and novelty of some of the sixties communes, such as Drop City, often distracted both contemporary and historical observers from the seriousness with which their founders challenged prevailing social and economic relations.

Recent historical scholarship has challenged these simplifications, and one of the most interesting revelations is the degree to which many of the unconventional methods and radical aspirations of the sixties countercultures were, in fact, profoundly continuous with the ethical, philosophical, and aesthetically radical ambitions of the prewar avant-gardes. Nowhere are these connections clearer than in the use of craft to disrupt conventional boundaries between art and life. From the Blue Rider to the Russian Futurists to the Bauhaus, early twentieth-century vanguard artists turned to forms of making that eschewed the elevated status of fine art, in order to liberate themselves from the material and aesthetic restrictions that accompanied that privileged status. These same goals are demonstrated very clearly in Camphill Village Copake, Chardavogne Barn, and, to a lesser degree, the Fellowship Community at Threefold Educational Center. All three are located in the Hudson Valley, are affiliated with alternative religions, and, most importantly, place craft at the center of their community practice.

The Fellowship Community, a residential community for the elderly, and Camphill Village Copake, a integrated residential community that serves developmentally disabled adults, are both affiliated with Anthroposophy, the religion/philosophy created by Rudolf Steiner in 1913. Chardavogne Barn was founded by followers of the Georgian-Russian mystic Gyorgy Gurdjieff, whose belief system is sometimes called the Fourth Way, but Chardavogne members refer to it simply as “the Work.”[2] Both Steiner’s Anthroposophy and Gurdjieff’s teachings were crucial to the utopian aspirations of modernist innovators before the Second World War. Steiner counted among his followers Vassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Hilma af Klint, Andrei Belyi, and Wharton Esherick, to name a few.[3] The list of those influenced by Gurdjieff includes such disparate figures as the group of Russian Futurists centered around Natalya Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov and the Harlem Renaissance author Jean Toomer.[4]

This issue’s theme of “clubs” provides an interesting framework for understanding the function and organization of these communities. The clubs to which Chardavogne Barn or Camphill Village Copake bear the simplest comparison, of course, are amateur craft clubs, a long-evolving and wildly diverse phenomenon that, like this essay’s subjects, privileged skill acquisition and self-improvement through labor. As Stephen Knott examines in his book Amateur Craft, the demonstration of leisure through amateur pursuits that characterized aristocratic and haute bourgeois culture was soon transformed into the middle-class aspiration toward both productivity and moral virtue through work.[5] In some ways, the communities I discuss fit within these parameters. Members of both the Gurdjieff and Steiner groups were from predominantly middle-class backgrounds. In the value placed on work and on productivity for its own sake, their practices resembled capitalist ideals of alienated and rationalized labor.

That resemblance, however, may be largely superficial. With their sober philosophical frameworks, mandated work ethic, and rejection of conventional rationality and capitalist efficiency, Gurdjieff groups like Chardavogne Barn or the Steiner-based Camphill Village look a lot like the utopian vanguards—such as the Bauhaus, De Stijl, or Constructivism—that were informed by an earlier generation of Gurdjieff and Steiner enthusiasts. Though their somewhat “square” appearances may contrast with the “hip” movements and communities of their own time, Chardavogne Barn and Camphill Village Copake certainly constitute one of the bridges through which the “counterethics” (to use Timothy Miller’s phrase) of the sixties counterculture were created out of earlier vanguard movements. Counterethics, according to Miller, one of the most prominent historians of both the American counterculture and intentional communities, “offered an innovative appraisal of American culture and promulgated creative, if unorthodox, guidelines for conduct in a rapidly changing cultural milieu.”[6] Though their members didn’t have long hair, do drugs, or practice free love, Chardavogne Barn, Camphill Village, and the Fellowship Community were formidable models of the collectivist anti-capitalism, environmental consciousness, and challenge to rationality that formed the basis of the counterethics.[7]

One of the most interesting things about these communities is that they have endured, and even thrived, for more than half a century, but have nonetheless remained on the margins of our understanding of art, craft, or counterculture communities. Like the “hobby” craft groups Julia Bryan-Wilson explores in Fray, these communities comfortably inhabit Gregory Sholette’s notion of “creative dark matter.”[8] In Sholette’s formulation, creative dark matter is the functional foundation of the art world—the underpaid (or unpaid) labor force, the consumers of printed matter, and the enthralled audience. The invisibility of this mass to the individuals and institutions that control the art world (hence its analogy to astronomical dark matter) is necessary to the heroic narratives of individuality and autonomy that justifies art’s elevated status. But the communities I discuss here also relate to another aspect of Sholette’s creative dark matter; there is a contingent of artists who, by eschewing the goals of heroic visibility, choose to be on the margins.[9] In both the Steiner and Gurdjieff communities, the underlying spiritual and aesthetic ambitions kept both elite art and consumerist mass culture at bay, creating space for an embodied creativity by otherwise marginalized makers.

The Anthroposophical Communities—Camphill Village Copake and the Fellowship Community

Anthroposophy occupies an ambiguous position in the world of modern alternative religions. Though it has a full complement of esoteric and spiritual elements, the actual practice of Anthroposophy is primarily located in its pedagogical (Waldorf education), agricultural (biodynamic farming), and therapeutic (the Camphill movement) philosophies. Originally an offshoot of Theosophy (Rudolf Steiner was the head of the German Theosophical Society when he broke with the group in 1913), Anthroposophy has spread globally and outpaced Theosophy, if not in absolute membership, then in its far-reaching integration with everyday life. North Americans and Western Europeans, in particular, buy food, cosmetics, and even financial services created according to Anthroposophical principles without knowing anything about the movement or even having heard of it.[10] The most widely recognized manifestation of Anthroposophy is Waldorf education, which has long been an important force in the North American alternative education movement.

As a modern religion without strong institutional mechanisms for enforcing doctrinal correctness, Anthroposophical beliefs present significant diversity. In his description of the spiritual foundations of the Camphill movement, Jan Martin Bang writes that, “Anthroposophy proposes the physical world as a development and outgrowth of the spiritual world, and presents a scientific method of analyzing this spiritual world.”[11] Unlike mainstream Christianity, which tends to emphasize the heavenly and spiritual at the expense of the worldly and material, Anthroposophical practice cultivates an increased attentiveness to the material world, without which the connection to spirit would remain unknowable. In many of the different branches of Anthroposophy, craft functions as a method for developing this fuller awareness of the material world and its properties. This was part of the draw of Anthroposophy for the poet and potter M.C. (Mary Caroline) Richards, whose 1964 book Centering: In Pottery, Poetry, and the Person forged an unbreakable association between craft and spirituality in postwar America. Already deeply engaged with Anthroposophy and the Camphill movement at the time of writing Centering, Richards later deepened her involvement. In 1980, she wrote Toward Wholeness: Rudolf Steiner Education in America, in which she claimed that the goal of Anthroposophy is “the union of inner experience and sensory life.”[12] In this capacity, craft has a distinct therapeutic and social role.[13] For the developmentally disabled villagers at Camphill Village Copake or the elderly residents of the Fellowship Community, participants’ work in craft is understood as both a therapeutic activity and a social practice, improving the well-being of both the individual residents and the social relations within the community.

Steiner believed that design and material culture had a profound effect on people’s mental, physical, and spiritual fitness. For one thing, Steiner (and those who continued his practice after his death in 1925) had very specific ideas about the appropriateness of both form and decorative elements to an object’s function. This is seen very clearly in the distinctiveness of Anthroposophical architecture and design.[14]

Steiner believed that the overwhelming materialism of modernity created a pernicious barrier between our inner life and intuition, on the one hand, and our objective understanding of sensory experience, on the other.[15] The importance of craft has to do with this: remediating the connections between inner feeling and sensory perception. This concept is most easily exemplified in the Waldorf educational emphasis on handwork. In Waldorf handwork, children are taught to integrate the function of an object with its design. The form of something hand-held, such as Waldorf trainer Margaret Frohlich’s serving bowl, should clearly fit the grip of the human hand.[16] Moreover, the decorative elements of the work should also provide clear indication of, and allow for, its intended use—a pillowcase, for example, should not have an embroidery pattern that would imprint itself on a sleeper’s check.[17] While Waldorf handwork is meant to cultivate a synthesis of materiality, beauty, and practicality in children, many Anthroposophists saw Steiner’s principles as having a therapeutic as well as a pedagogical function. Frohlich’s serving bowl is itself an example of the seamless exportation of Waldorf educational methods into other areas of Anthroposophical practice. After an extensive career as a Waldorf teacher and teacher trainer, Margaret Frohlich retired to the Fellowship Community at Threefold Educational Center, where she continued to teach various forms of handwork.[18] Established in 1966, the Fellowship Community’s mission is to remedy the mechanization and isolation of eldercare through the principles of Anthroposophy. The Community has a weavery, candle shop, joinery, and pottery, along with a farm and dairy. These occupations serve as therapeutic activities for the elderly residents with physical and cognitive impairments. In the case of Frohlich’s handwork, the principles Steiner developed in the context of child development were extrapolated into a wider use for handicraft. Handicraft is a way for people to integrate their physical experience in manual labor with their spiritual experience in aesthetic contemplation, and with their intellectual experience in design and problem solving. The use of natural materials and simple tools is also important, since it affirms the direct connection between creative will (the maker’s intentions and actions) and the sensible material world.

This concept of instrumentalizing craft for therapeutic purposes is even more explicit in the Camphill Movement. The first Camphills were created during World War II by Karl Konig and a group of other Austrian refugees who fled to Britain in advance of the Nazi occupation. Camphill Villages are designed to give residential care and therapeutic education to developmentally disabled adults. [19] In a turn of phrase some may find dystopic, these residents of Camphill are called “villagers.” Founded in 1961, Copake was the first Camphill Village in the United States, and is still known among other Camphills for its emphasis on craft production.

The largest and most prolific of the workshops at Camphill Village Copake is the woodshop, which has created everything from trivets and cutting boards to simple wooden toys and blocks, and even furniture.[20] The weavery, candle shop, glass shop, and bookbindery are also very active. For the most part, the objects they produce are relatively simple, and there is no expectation that Camphill villagers, who do the lion’s share of the craft labor, will become virtuosic craftspeople.

Residents working in the Woodshop, Camphill Village Copake. Date unknown. Photograph by Asger Elmquist.

Indeed, virtuosity is not central to the Camphill ethos. The co-workers who supervise the villagers rarely have previous training in their work; the usual practice is that a co-worker takes over a workshop and learns on the job. (The major exception to this has been the glass shop, which has not been operational since 2017. In the glass shop, the bulk of the labor was done by co-workers, as most villagers don’t have the skill to execute the ambitious designs the shop carried out.) These circumstances put a heavier burden on design and problem solving, with design work often based on the individual skills of the villagers. If a villager really likes small detailed work, for example, that is the design the co-worker creates or the work process she facilitates. Camphill co-workers told me that people on the autism spectrum, for example, tended to enjoy delicate joinery work, whereas villagers with less fine motor control had more success dipping candles.[21]

These simple objects made of natural materials, often sourced from the village itself, provide the opportunity for what Richards called “the union of inner experience and sensory life.” Because the maker can see the full process of transformation, they get a holistic view of the relationship between their own will and the material world upon which they act. The wool of sheep, pastured and shorn on Camphill grounds, is then treated, carded, spun, and woven into functional objects. As one co-worker pointed out to me, this grounding in physical reality is especially important for villagers with cognitive disorders; for people with a troubled or challenging relation to reality, simple craftwork using natural materials is an opportunity to fully trust their sense impressions.[22]

In addition to this therapeutic value, both Camphill Village and the Fellowship Community understand craft as a social practice. It is essential that the products resulting from villagers’ labor be useful and marketable. The co-workers who run a shop must create designs that are appropriate to the villagers’ skills but also contribute to the entire village’s needs. A bicycle flour mill, for example, was developed for a villager who was obsessed with bicycles but didn’t have the physical coordination to ride one. The co-worker’s design integrated the villager’s love of cycling with the bakery’s need for freshly-milled flour.[23]

According to Camphill co-workers, this reframing of craft labor is a restoration of the villagers’ human dignity. In contrast to the outside world, where the developmentally disabled are understood as burdensome outcasts, the craft and agricultural products created at Camphill demonstrate the villagers’ meaningful contribution to their community. By creating products that are desirable to each other and to the outside world, the disabled villagers can both assert and experience their value to the social body. [24]

A similar model also informs the Fellowship Community’s use of craft. Candles, ceramics, and other goods created by Fellowship residents are sold at the Community’s store and café, as well as at other venues within the Threefold Educational Center. The Fellowship woodshop also creates rocker boards, which are sold to Waldorf schools. At an annual and well-attended Christmas event, proceeds from the sale of Fellowship-made goods are set aside to pay tuition for coworkers’ children at Green Meadow Waldorf School.[25] Like at Camphill Village, the Fellowship community uses the residents’ craft production to counter the social isolation and sense of burden projected onto the elderly.

Chardovogne Barn

The Gurdjieff group at Chardavogne Barn shares with the Anthroposophical communities a belief that the combination of repetition and finesse in craft labor is a way to achieve spiritual reintegration. Steiner’s call for the union of our physical, intellectual, and spiritual selves maps closely onto the Gurdjieff understanding of a person’s three centers—will, emotion, and physical being.[26] According to the Chardavogne craftspeople I interviewed, the intense focus and coordination of fine handwork allows them to unite these three centers, thereby cultivating an objective or universal spiritual quality.[27] This combination of manual labor and focused attention is “the Work.” Despite this similarity between Steiner’s and Gurdjieff’s ideas, the communities, and the work that comes out of them, are quite different.

Chardavogne Barn was founded in 1967 by a group of Gurdjieff devotees led by Willem Nyland, a German chemist who emigrated to the US in the 1940s. Together they rebuilt a barn in Warwick, New York, adding a pottery, weavery, metal shop, greenhouse, and gardens, along with a house for Mr. Nyland. None of the other participants lived on the property; they all simply bought or rented homes nearby. Chardavogne was not, therefore, self-contained and self-sustaining like Camphill Village or the Fellowship. But the energy and dedication of the group led to a robust community.[28]

Chardavogne members who set up private businesses in the town of Warwick—such as a health food store and a plumbing service—tithed to the Barn. But there were also a few ventures that were developed collectively—a daycare center and a school, a bakery, and what was known as Chardavogne Barn Activities, a shop and wholesale distributor for the craftspeople in the group. These collective ventures, in addition to the regularly scheduled “workdays,” when community members would come together to practice the Work, created a broader informal network of mutual reliance and interdependence.[29] This collectivity was not incidental; Nyland argued that the discipline and self-awareness necessary to unify your centers and develop a truly objective awareness was only possible within a group that shared this spiritual ambition. In order to maintain honesty and accountability, you should witness other people’s Work, and they should witness yours.[30]

Because the group saw craft as a way to practice The Work, skilled production was not their primary goal. The work could be practiced using the most menial labor. For example, Nyland used to have members repeatedly pick up a suitcase and walk with it from one corner of a room to another.[31] But the fact that craft produced something objective did give it additional spiritual value. Speaking of the prevalence of craft among the group, Nyland said:

What is the reason for a craft? Not just to make a couple of pots that you can sell in the store….Your work, the way you look at producing something, the way you look at creation, the way you look at the possibility of form, making something for the sake of wanting that form to contain something of your life – and if possible, not only your life but what makes your life your life, the essence of your essence, the question of Being.[32]

Once again, we see the similarity between the Gurdjieff and Steiner ideals. Craft is useful not only because handwork has therapeutic or spiritual utility, but because the objective material qualities of the product heightens awareness of the connection between the inner life of our intuition or will, and our sensory experience of the material world.

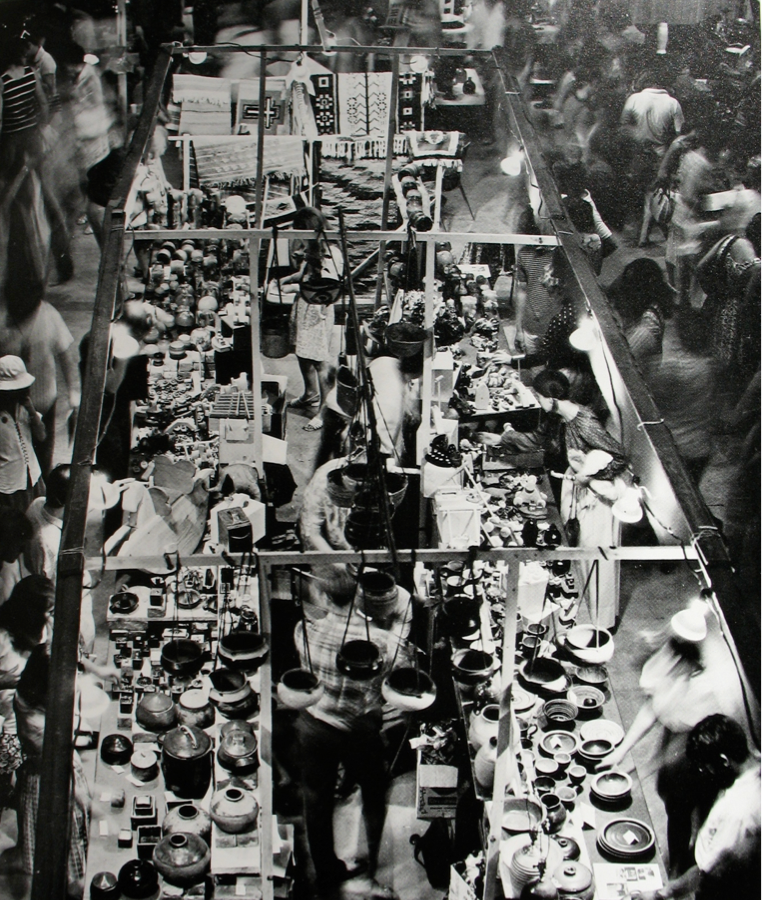

Even at the founding of the group, some of the early members had already taken to craft as a countercultural alternative to conventional employment, but their work was somewhat crude and not concerned with mastery or skill. As a result of their rigorous practice, however, the Chardavogne craftspeople became a successful and highly visible presence in the growing craft market of the 1970s. For example, there was an entire section of the 1971 Northeast Craft Fair devoted to Chardavogne Barn Activities.[33]

Two of the Chardovogne craftspeople I interviewed experienced this transformation of their professional practice. Harvey Greenwald and Jacques Hemsi were both founding members of the group and their careers as a leatherworker and a jeweler, respectively, spanned half a century.

Greenwald’s early work (in the photo, selling his wares from cardboard boxes at Woodstock) displayed a simple DIY sensibility that reflected his engagement in the counterculture. Hemsi, on the other hand, had a graduate degree in philosophy, but, in his own recollection, didn’t want a job, so he started making somewhat crude jewelry, simply as a way to make some cash. After they became regulars at Nyland’s Gurdjieff study meetings in NY, Both Hemsi and Greenwald curtailed their drug use and general carousing and submitted to the discipline and rigor of the Gurdjieff Work. [34] These changes certainly had a transformative effect on both their lives and artistic practices. In later examples of their work we see the increasing sophistication of the studio craft movement and its growing commonality with luxury commerce.

Chardavogne craftspeople like Greenwald and Hemsi were able to marshal the spiritual work of craft to further their individual development as makers, achieving consistent levels of professional success. This could not be more different than the anonymity and collective orientation of craft in Camphill Village or the Fellowship Community. Despite these differences, however, both the Steiner and Gurdjieff communities discussed here have maintained a high degree of continuity in their practice and integrity with their original ambitions. In the case of Camphill Village and the Fellowship Community, this required that they continually defy the pressure toward brutal efficiency in institutional care for the elderly and the disabled. For Camphill Village Copake, this resistance is even more notable, since they receive New York state funding for many of their villagers.[35]

At the same time, these communities demonstrate resistance to a different kind of pressure, one that is not about efficiency, but rather about the aesthetic vagaries of art and fashion. Despite the close connections between Steiner, Gurdjieff, and early twentieth-century modernism, the work produced in these communities rarely conforms to modernist criteria of “good design.” M.C. Richards, Janet Leach, and the graphic designer Ilonka Karasz are among those who were in direct exchange with both these spiritual communities and the worlds of contemporary art and design, but it is no surprise that these exchanges have yet to be examined in any serious way. The Steiner and Gurdjieff communities’ resistance to both “good design” and the dematerialized sensibility of vanguard art of the 1960-70s makes them an uncomfortable subject for historians of modern and contemporary art. As mentioned earlier, Greg Sholette’s concept of creative dark matter is a compelling explanation for the continued invisibility of these communities, despite their various connections to the worlds of art, studio craft, and design. Creative dark matter, comprising collective skills and resources, must remain invisible lest it undermine the heroic autonomous narrative of artistic labor. But the collective, contingent, and spiritually instrumentalized character of the Gurdjieff and Steiner communities’ work puts them in a particular category of dark matter, the type Sholette identifies as “those artists who self-consciously choose to work on the outer margins of the mainstream art world for reasons of social, economic, and political critique.” [36] Neither the Gurdjieff nor Steiner communities are outwardly political, certainly not in a partisan sense, but Sholette’s definition of politics is generous and expansive enough to include their spiritually-oriented forms of labor and production: “Here ‘politics’ must be understood as the imaginative exploration of ideas, the pleasure of communication, the exchange of education, and the construction of fantasy, all within a radically defined social-artist practice.”[37] It is interesting, however, that the examples he includes in Dark Matter conform to a much narrower definition of politics; the artists he discusses engage in either direct social action or political debates within a roughly Marxist framework.

From this subtle disconnect between Sholette’s definition of politics and his examples, we see the glimmer of another reason that these communities have remained invisible within the history of American art; the association of art with therapeutic or spiritual utility has long been a criterion for aesthetic dismissal. As Clement Greenberg argued in “Modernist Painting,” the worst possible fate for the arts was to be assimilated, like religion, into the service of therapy:

We know what has happened to an activity like religion, which could not avail itself of Kantian, immanent, criticism in order to justify itself. At first glance the arts might seem to have been in a situation like religion’s. Having been denied by the Enlightenment all tasks they could take seriously, they looked as though they were going to be assimilated to entertainment pure and simple, and entertainment itself looked as though it were going to be assimilated, like religion, to therapy. The arts could save themselves from this leveling down only by demonstrating that the kind of experience they provided was valuable in its own right and not to be obtained from any other kind of activity.[38]

It is not surprising, then, that artists whose work was conceived as therapeutic were written out of the history of modern and postwar art. As Jenni Sorkin argues in Live Form: Women, Ceramics, and Community, the popularity of ceramics as a treatment for trauma in veterans was soon recast and masculinized as Zen, and later Cagean, aesthetics, while M.C. Richards’s calls for healing and wholeness resulted in her continued marginality in the history of American vanguard art and poetry.[39] The Steiner communities—the Fellowship and Camphill Village—used craft as both pedagogical and therapeutic tools, while the Gurdjieff group at Chardavogne Barn positioned it as an instrument of spiritual development. And it was exactly in these capacities that they served as models and inspirations to other artists. Through these examples we can continue the work of recognizing that postwar American art was more diverse in its philosophical ambitions than standard histories of the modern and postmodern have acknowledged.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Camphill Village Copake only serves individuals with developmental disabilities; it does not also serve individuals with mental illness.

[1] Erin Elder, “How to Build a Commune,” in West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America, 1965-1977, Elissa Auther and Adam Lerner, eds. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 4.

[2] See George Baker and Walter Driscoll, “Gurdjieff in America: An Overview,” in America’s Alternative Religions, ed. Timothy Miller (Albany: SUNY Press, 1996), 259-65. Sarah Warren, interview with Harvey Greenwald, March 8, 2014; interview with Jacques Hemsi, May 12, 2014; interview with Betty Greenwald, March 16, 2019.

[3] See Maurice Tuchman, ed., The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, (New York: Abbeville Press, 1986); Tracey Bashkoff, ed., Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2018); Roberta A. Mayer and Mark Sfirri, “Early Expressions of Anthroposophical Design in America: The Influence of Rudolf Steiner on Fritz Westhoff and Wharton Esherick,” Journal of Modern Craft, vol. 2, issue 3 (November 2009), 299-324.

[4] The Russian Futurists were influenced by Gurdjieff through the intermediary of Petr Ouspensky, whose Tertium Organum (1912) related theories of the fourth dimension to contemporary mystical pursuits. See Anthony Parton, Mikhail Larionov and the Russian Avant-Garde, (Princeton, 1993); Jon Woodson, To Make a New Race: Gurdjieff, Toomer, and the Harlem Renaissance, (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1999).

[5] Stephen Knott, Amateur Craft: History and Theory (London: Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2015), xiii-xiv.

[6] Timothy Miller, The Hippies and American Values. Second Edition, (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2011), xv. First Edition, 1991

[7] Miller, The Hippies, 106-109.

[8] Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 32.

[9] Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (New York: Pluto Press, 2011), 1-4.

[10] Among the most well-known Anthroposophical manufacturers of cosmetics and personal care products are Weleda, Wala, and Dr. Hauschka. In the Northeastern United States, such biodynamic farms as Seven Stars Farm and Hawthorne Valley Farm have their dairy and fermented products widely distributed to mainstream groceries.

[11] Jan Martin Bang, “Spirituality in the Camphill Villages,” Spiritual and Visionary Communities: Out to Save the World, ed. Timothy Miller, (Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), 109.

[12] M.C. Richards, Toward Wholeness: Rudolf Steiner Education in America (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1980), 3.

[13] M.C. Richards herself later became a Camphill co-worker and ran the pot shop at Camphill Village Kimberton Hills, but she was also an advocate for and participated in the founding of Camphill Village Copake, giving a speech at the dedication of Fountain Hall, the central community and event building in Camphill Village Copake. Richards later wrote a poem about the experience, “Chief Crazy Horse at Fountain Hall.” Richards, Wholeness, 17-18.

[14] See David Adams, “Rudolf Steiner’s First Goetheanum as an Illustration of Organic Functionalism,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 51, No. 2 (June 1992), 182-204.

[15] See Rudolf Steiner, “Chapter 1: The Essential Nature of the Human Being,” Theosophy (1922), trans. Catherine E. Creeger, (Great Barrington, MA: Anthroposophic Press, 1994), 21-62.

[16] Adams, “Organic Functionalism: An Important Principle of the Visual Arts in Waldorf School Crafts and Architecture,” Waldorf Research Bulletin, Vol. X, No. 1 (Spring 2005), 8-9.

[17] Adams, “Organic Functionalism,” 5-6.

[18] David Adams, correspondence with author, February 12, 2014. Sarah Warren, Interview with Larry Fox, April 4, 2014. Warren, Interview with Liesl Winters (neé Frohlich) and Renate Hiller, May 16, 2014.

[19] Bang, “Spirituality in the Camphill Villages,” 103-4.

[20] Warren, Interview with Marty Hunt and other Camphill Village Copake co-workers, April 25, 2014. At one point in the 1980s, the woodshop at Camphill Village was manufacturing beds for a large retailer.

[21] Warren, Interview with Marty Hunt and Camphill co-workers.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Warren, Interview with Larry Fox, April 4, 2014.

[26] Baker and Driscoll, “Gurdjieff in America,” 261-2.

[27] Warren, Interviews with Greenwald, Hemsi, and Greenwald.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Warren, Interview with Betty Greenwald.

[30] Willem Nyland, Chardavogne Barn, (Warwick, NY: Gage Hill Press, 1983), 78-80.

[31] Warren, Interviews with Greenwald, Hemsi, and Greenwald.

[32] Nyland, Chardavogne Barn, 32.

[33] ACC archives.

[34] Warren, Interviews with Harvey Greenwald and Jacques Hemsi.

[35] Warren, Interview with Marty Hunt and Camphill co-workers.

[36] Sholette, 3-4.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, v. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969, ed. John O’Brian, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 85-86.

[39] Jenni Sorkin, Live Form: Women, Ceramics, and Community, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 139-44, 197.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.