Banana Consciousness

Like countless children in the U.S., I grew up with a parent holding a butter knife in one hand and a banana in the other, cutting the pale fruit into irregular slices over a bowl of cereal flakes mounded in a pool of cold milk. Perhaps the banana cannot be untangled from personal recollection and private moments of consumption, from boxed cereal, childhood, banana splits, and vanilla wafers layered in banana pudding. Roland Barthes writes about a type of varnished food made for the glossy pages of the lifestyle magazine, food buried under “the uneven sediments of sauces, creams, icing and jellies,” a “cooking for the eye alone” and a “cuisine of advertisement” perfectly molded by the focus group and public relations expert.[1] Along with Barthes, artist Ricky Yanas’s inquiry-based project, Banana Tree, motivates much of this text. Part of the work features a series of digital collages that piece together collectable ephemera, advertisement images, and historical research about the politics and impact of banana production in Central America and the Caribbean. On the phone Yanas tells me there is no such thing as a banana tree, that the banana grows from a plant. The fictitious idea of the “banana tree” suggests the banana can only be understood as myth, but a myth with a wide-reaching material genealogy. As such, the history of the banana is a social and economic history caught up in global flows and patterns of consumption, resource extraction, capitalism, neocolonization, and US intervention in Latin America.

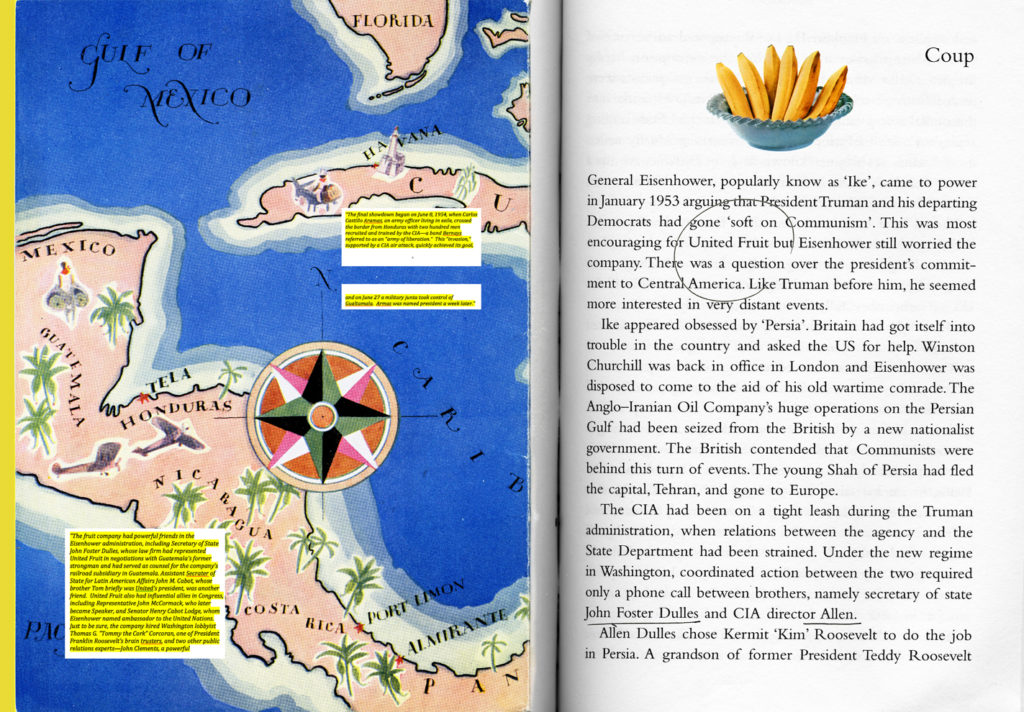

Coup, from the series Banana Tree. Face-mounted Inkjet Print, 16″ x 26″ (2014). Courtesy of Ricky Yanas.

At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century the United Fruit Company was founded through the merging of several already sizable U.S.-based fruit trading businesses. Operating out of Boston and then New Orleans, the corporation grew to great size financially, in land holdings and political influence. By the 1930s, they possessed over three million acres of banana plantations in Central American and the Caribbean and wielded extensive power over the governments of those non-industrial countries dependent on a single export.[2] Such colonial economies, often vertically integrated monopolies, are doubly negative in a sense; they generate wealth through abusive circumstances of extraction and then whisk that wealth far away to the sole benefit of distant imperial markets and their agents. A peripheral social sphere is transformed into a financialized appendage, a series of “banana republics” dedicated to neo-feudal land use and the cheapest production possible. As far as food goes, tropical fruit seems especially fraught, a result of its colonial connections to the central engines of global trade and global domination. Given the psycho-social spheres certain food emerges from and the practices and people it invokes, what does it mean to take into the body the culmination of an imperial process, a simultaneously complex and concealing progression of reification and commodification responsible for the production of the local grocery store banana?

To buy anything, especially items of convenience and excess (like fast food), my grandparents had to drive into town. They lived on a few outlying acres punctuated by low growing mesquite trees and groves of flat disc-shaped cactus. The grandchildren sat in the back of the truck—some on the floor, some on the wheel wells, some on the edge of the bed. Once inside the Dairy Queen we gazed at the rows of frozen bananas sidled together and glazed in delicate layers of tempered chocolate as thin and elusive as the shine of lacquer. They lay there in curved earnestness, run through with a thin stick like a popsicle, just behind and beyond the clear horizontal sliding doors of a small stand-alone cooler. Situated by the cashier, it was perfect for children—elongated, on tippy-toes, in discount sneakers. Gleaming graphics flowed in every direction. We were constituted as hamburger, ice cream, and frozen banana eaters. The psychoanalyst has much to say about such things, about the hidden urges leftover from our archaic and arcane pre-histories, about the repression that must be engaged unless we become permanent social discontents, about visual consumption, the pleasure of looking, about the longing we construct and are constructed by. Despite everything, we were allowed to slide the glass door open and select our frozen chocolate bananas. To self-serve.

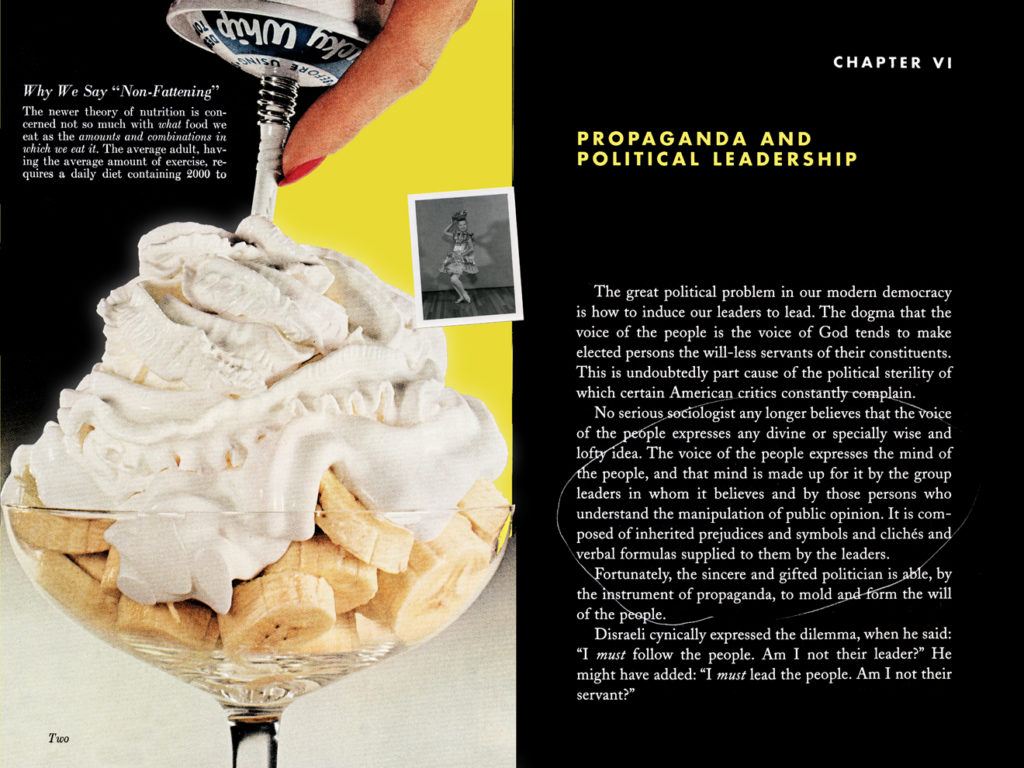

Propaganda and Political Leadership, from the series Banana Tree. Face-mounted Inkjet Print, 18″ x24″ (2014). Courtesy of Ricky Yanas.

Edward Bernays, inventor of public relations and nephew of Sigmund Freud, is largely associated with the now-universal corporate practice of connecting emotions to products and, more importantly, with transforming the notion of the shopper from a practical being who weighs factual information to a modern figure driven by passions of consumption. Much of Bernays’ approach to commodities and consumers borrowed from psychoanalytic theory. If the masses are driven by illogical, disruptive, internal energies they cannot be trusted with democracy, which should always be a smooth-running zone where capitalism can function unworried. The multitudes left to their own impulses would only produce a multitudinous world with no central or unified rationale.[3] Reasonable rule meant rule by those elite who “govern us by their qualities of natural leadership, their ability to supply needed ideas and by their key positions in the social structure,” by those “who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses.”[4] The intense effort required for the public to be politically informed had to be replaced by something far more convincing and succinct—a narrative of desire. For Bernays, commodities worked in the same way. In order to avoid the hopeless gridlock that would come with the total propagation of goods and services, Bernays writes, “society consents to have its choice narrowed to ideas and objects brought to its attention through propaganda of all kinds.”[5] Two of the many products Bernays represented in his public relations practice were capitalism and democracy. The two lived inside each other and both required an emotional narrative consistent with advertisement to function properly.

My mother sang a cheerful tune around the house, a 1990s jingle: “I’m Chiquita Banana and I’m here to say, I am the top banana in the world today…” The jingle is based on an animated commercial produced by Disney and shown in movie theaters in the 1940s. The cartoon scene opens onto the curved horizon of an unnamed sea, a white boat in the distance. The United Fruit Company owned a large fleet of refrigerated cargo ships, referred to as the Great White Fleet. After the cartoon boat ports, a banana personified as a tropical cabaret singer in ruffled sleeves disembarks. Her song instructs the viewer on the value of eating bananas, how to ascertain their ripeness, why they should be kept out of refrigerators, and how to incorporate them in cooking.

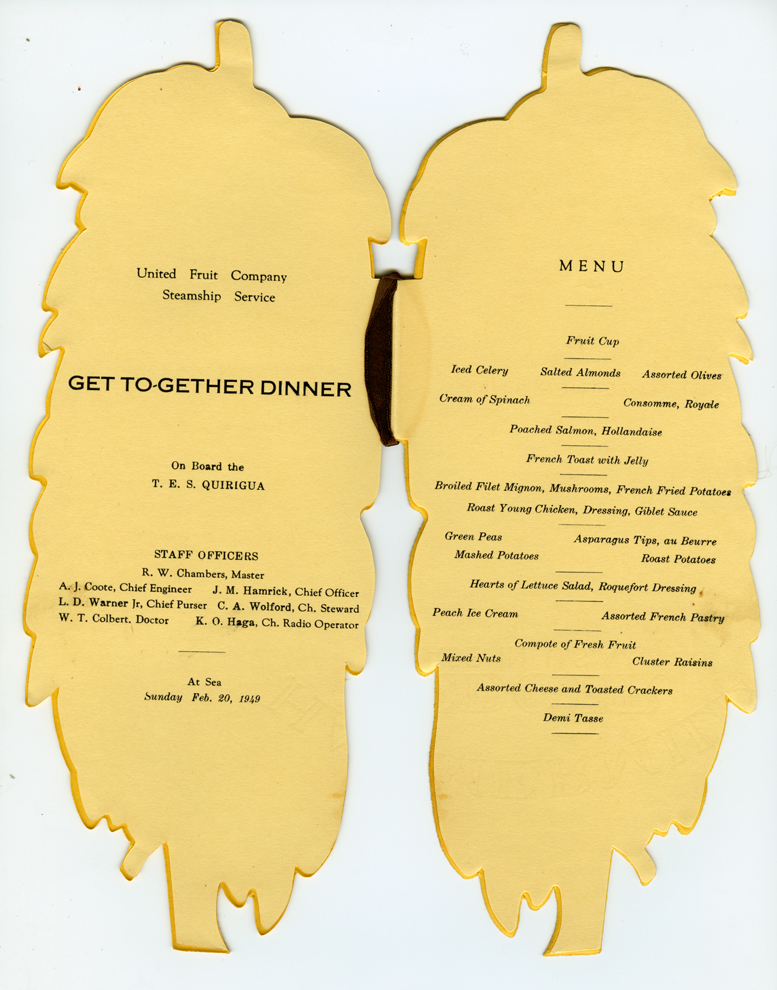

United Fruit Company Steamship Service Menu, TES Quirigua, c.1949, from the collection of Ricky Yanas.

She wears a fruit hat made popular by Carmen Miranda, the type based on the laborious gesture of stacking and balancing bunches of bananas on the harvester’s head.[6] In fact, the commercial is based on a performance given by Miranda in Busby Berkeley’s 1943 film The Gang’s All Here.[7] For Miranda’s scene, the solemnity of the planation is transformed into a fantastic panorama where “banana tree” leaves drape and cascade like a stage curtain.

The aesthetics of repetition play out in the rows and rows of prop bananas and prop banana plants, in the lines of female dancers enmeshed in Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic and ludic choreography. Such aesthetics of recursion take on an undeniable grimness when considered in relation to the rows and rows of workers required on the United Fruit Company’s vast banana plantations. The kaleidoscope of necropolitics refracts the countless laboring bodies invoked by the harvest of bananas, a necrocurrency hauled in immense numbers from the periphery to the center by The Great White Fleet.[8] The demands of foreign markets extract, but they also send things back. In addition to shipping bananas, the United Fruit Company booked passage to the Caribbean and organized elaborate travel excursions.

United Fruit Company Steamship Service Menu, TES Quirigua, c.1949, from the collection of Ricky Yanas.

The first Banana Republic I encountered was a clothing store. Young and more interested in the disarray of thrift stores than the antiseptic and glimmering disparity of the mall, I had an uneasy feeling. Piecing together the logics of colonialism and Victorian-era social construction were far off, but my outcast’s mistrust was ever-present. Originally named Banana Republic Travel & Safari Clothing Company, the apparel store, founded in the late 1970s, became ubiquitous after its acquisition by Gap in the 1980s. Rebranded simply as Banana Republic, the aristocratically earthy purveyor catered to a neocolonial fantasy of tourism, exploration, and general wanderlust. The company summoned an imaginary country where ventilated tropical dresses, safari bangles, handcrafted trench coats, houndstooth jackets, and flight suits are forever strewn across roughhewn packing crates, military-style jeeps, and twin prop airplanes permanently ensconced deep within an illusory colonial territory, a tropical bird always nearby. The original catalogues are known for their hand-drawn illustrations and fictional travel stories. Historically, travel writing contributed to the consolidation of the imperial image through comparison to a distant other. As Claire Lindsay writes in her essay “Travel Writing and Postcolonial Studies,” it aided to “generate curiosity, excitement and adventure” and was “instrumental in the economy and machinery of Empire.”[10] Of course, no history ever stays in the past; forms of domination return in various iterations. Jacopo Peterman, Elaine Benes’s boss in the last three seasons of Seinfeld, was based on John Peterman, founder of The J. Peterman Company, a business that followed the safari and travel theme of Banana Republic (selling mostly through catalogs and the internet). Both businesses, in reality and in the televisual imaginary, marked a space where the instruments of colonization and imperialism were sanitized and became an aesthetic lifestyle campaign aimed at individuals who preferred modest things not so modestly priced, who felt most comfortable with products that would narrate their “sense of ownership, entitlement and legitimacy” regarding distant domains.[11]

In 1954, the CIA and the United Fruit Company overthrew the Guatemalan government and ousted the president. Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was inaugurated with a landslide majority based on his popular land and labor reformation platform, which directly challenged the holdings, practices, and political influence of the United Fruit Company. As an agrarian reformer Guzmán sought to dictate government buy-backs of fallow plantation territory owned by the banana corporation. Prices were set according to how the company valued these lands in their tax documents. The politics of land rights and usage were of vital concern to the United Fruit Company, which benefited greatly from the impending regime change. Bernays, in the employ of both the CIA and the United Fruit Company, shifted the conversation in Guatemala from the notion of virulent capitalism to the notion of sacrosanct democracy, transforming the aura of the popular regulatory social movement into a communist threat. As Bernays secretly fed US news outlets press releases linking Guzmán to Moscow and Moscow to Guatemala, the political landscape of Central and South America became increasingly framed as a Cold War issue. The eventual CIA-backed coup needed to be understood on the global stage and at home as the liberation of the Guatemalan people by freedom fighters and not as US interventionism at the behest of corporate sponsorship.[12] The history of land reformation in Central and South America is not a thing of the past; it remains a pronounced aspect of contemporary activism. According to a Global Witness report, 200 land and environmental activists were killed in 2016, noted as a particularly deadly year.[13] The possession and dispossession of territory in relation to corporate interests is a cycle of practices and repetition of structures marked by contemporary neoliberal geopolitics at home and abroad.

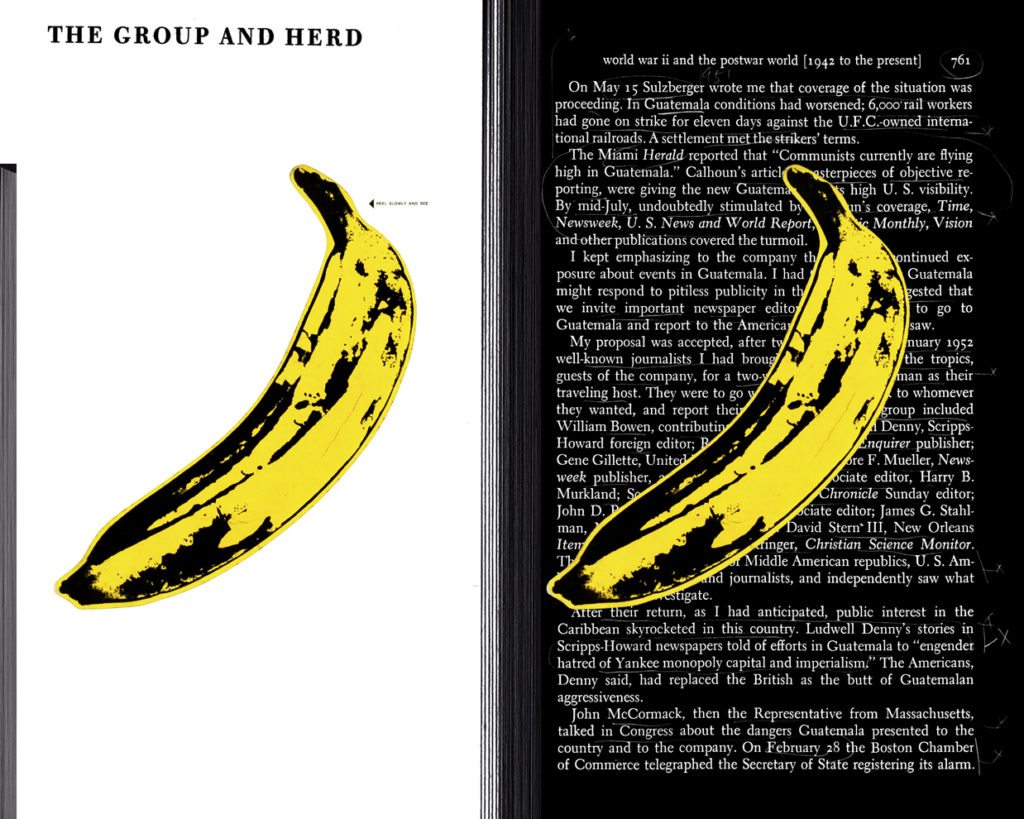

Crystallizing Public Opinion: The Group and the Herd, from the series Banana Tree. Face-mounted Inkjet Print, 16″ x 20″ (2014). Courtesy of Ricky Yanas.

A stylized map depicting parts of the Caribbean is digitally overlaid with small blocks of highlighted text. To the right is a scanned page from the book, Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. The names John Foster Dulles (Eisenhower’s Secretary of State) and Allen Dulles (Director of the CIA from 1951-61) are underlined. In another image, a small black-and-white photograph of a girl in a cabaret singer’s costume is photoshopped over an advertisement for whipped cream. She strikes a pose like a young Carmen Miranda. Next to her is a scanned page from Bernays’s 1928 book, Propaganda. A passage about the manipulation of public opinion is circled.

The images described above were made by Yanas for Northern Triangle, an exhibition responding to the 2014-2015 refugee crisis of unaccompanied Central American children apprehended at the US-Mexico border in Texas. Yanas’s project delineates a mode of study, a way of working through the vastly interconnected and looping historical echoes of destabilization by US political and military intervention in Central and South America. Rather than moving step-by-step from singular cause to singular effect, the arrangement of digital collages and material ephemera maps a field of causalities. Additionally, Banana Tree, and the exhibition the project was initially situated within, suggests such histories are never totally resolvable, that the present always contains and transmits the past’s multi-inscribed imprints of violence. Taking from M. Jacqui Alexander’s work on “palimpsest time,” one might say that the structures and markers of former oppressions, the politics of resource extraction, destabilization, capitalist consumption, interventionism, and the histories of imperial exploitation are only ever “imperfectly erased” as time passes.[14] Unprocessed and under-historicized, such imprints always return in uncanny, pathological hauntings, manifesting as various returning disasters, political neuroses, and national and international anxieties.

[1] Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972), 78.

[2] Grace Livingstone, America’s Backyard: The United States and Latin America from the Monroe Doctrine to the War on Terror (New York, London: Zed Books, 2009), 17.

[3] The Century of the Self. Directed by Adam Curtis. BBC Two, 2002, uploaded to Youtube July 9, 201. https://youtu.be/eJ3RzGoQC4s

[4] Edward Bernays, Propaganda (New York: Horace Liveright Inc., 1928), 9.

[5] Bernays, 9-10.

[6] For more information regarding the Chiquita Banana, including her interactions with racists representation of other cultures, see Trafaltz: http://tralfaz.blogspot.com/2017/01/the-educational-banana.html

[7] The Gang’s All Here. Directed by Busby Berkeley. Twentieth Century Fox, 1943. Youtube, https://youtu.be/TLsTUN1wVrc

[8] The term necropolitics comes from Achille Mbembé and Libby Meintjes’ essay “Necropolitics,” published in Public Culture. Vol 15. No. 1. (2003). I arrived at the term necrocurrency with Anthony Romero while discussing necropolitics, the colonial history of the banana, and recent monetary developments, like the rise of cryptocurrencies. The conversation was initiated by my recollection of a food vendor at the Logan Square Farmer’s Market in Chicago who takes Bitcoin.

[9] General information about Banana Republic can be found at the fan site Abandoned Republic: http://www.secretfanbase.com/banana/the-adventure-begins/

[10] Claire Lindsay, “Travel Writing and Postcolonial Studies” in The Routledge Companion to Travel Writing. Ed. Carl Thompson, (New York, London: Routledge, 2016), 25.

[11] Lindsay, 25

[12] Century of the Self. Directed by Adam Curtis.

[13] “Defenders of the Earth: Global killings of Land and Environmental Defenders in 2016,” Global Witness, July 13, 2017, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/defenders-earth/

[14] Alexander. M. Jacqui, Pedagogies of Crossing, Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2006), 189.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.