Austerity’s Fruit Ripens

Violets are Blue

Roses Are Red,

Teachers in Revolt Mean

Democracy’s Not Dead

Thirty-seven years ago, in the 1970s, the US labor movement had a short autumn. It quickly froze into a long, bleak and barren winter in 1981, when Ronald Reagan famously broke the PATCO (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization) strike by threatening to fire 13,000 employees unless they returned to work. Since then, it’s been a sometimes-slow, sometimes-scarily-speedy downhill slalom for union power and influence; wages have frozen while the wealthy have cracked away from the rest of the U.S. like calving ice. Not since 1929, or even the Victorian era, has the U.S. seen grinding poverty wear away at so many people.

Given all that, pro-labor people can be forgiven for celebrating some early signs of spring in late February 2018, when West Virginia teachers and other school workers shocked the country by shutting down every single district in the state—fifty-five in all—over a combination of grievances. Teachers and bus drivers, along with their friends, neighbors, students, and students’ parents formed red-T-shirted crowds. That ripe color recalled an early meaning of “redneck”: in the iconic Coal Wars, bandana-wearing miners in the West Virginia coalfields faced down both federal troops and the private police known as Pinkertons, an armed conflict that began in the 1880s and did not end until the 1930s, when unions won legal status. Reasons for the protests included awful wages and salaries, humiliating and expensive health insurance provisions, vanishing pensions, and the insulting levels of school funding endured since the economic crash of 2008. They were protesting a tax-cheat coal baron billionaire governor (ironically named Jim Justice) who ran as a Democrat only to switch parties upon winning his seat. And like early-blooming forsythia this February, they were just the bright beginning.

This spreading blush (more kudzu than red tide) is now known by its hashtag, #redfored.

It is a perennial falsehood that such uprisings are called “spontaneous.” This kind of storytelling tells us Rosa Parks, bone-weary, just sat down on the bus one day. Just like that. As opposed to: once upon a time, kids, our foremothers spent lifetimes cultivating generations of leadership, celebrated small successes and soothed failures, spent months making detailed plans, and carefully choreographed a kickoff to what became the Montgomery Bus Boycott. It took men and women, patience, dedication, and also no small amount of cash.

A seed of truth in the first type of telling is that a public stand of non-compliance can catalyze a new sense of the possible. The rest is the fertilizer.

We didn’t get all this overnight: it’s been a long growing season for austerity, as such political choices are known. It’s a sometimes boring story, the vague local, international, economic, and sociopolitical currents that converge into sharp disagreements about whether should have public (or as the right likes to call them, “government”) schools, who should pay for them, and whether the people who work in said schools should make enough money to feed themselves and their families. [1] Without taxes coming in, state governments have a hard time funding things like schools (or, for that matter, roads). Without consolidated worker power, it’s impossible to get governments, especially state governments, to raise taxes. Enter the 2008 recession, which further lowered tax revenues, especially for schools. Schools are often funded by local property taxes, the revenue from which went through the floor when home values dropped dramatically. States require their budgets to balance so when you’ve got nothing coming in? Budget cuts.[2] This leaves several unpopular options: eliminate schools (or parts of schools) altogether – arts programs, or even one school day a week, like in Oklahoma[3]; or privatization. Your biggest impediment, either way? Teachers organized into unions.

Underfunding public schools and converting them to private ones (via charter schools or voucher programs) is just one part of American Austerity, a multi-decade, bipartisan project. Noteworthy noxious examples including New Orleans[4] after Hurricane Katrina and Puerto Rico[5] in the wake of Hurricane Maria. But advocates don’t need a climate-change-induced crisis: Betsy DeVos did just fine without one in Michigan,[6] and Cory Booker’s rise to prominence was powered by Mark Zuckerberg’s financial commitments to similar experiments in Newark, NJ.[7] And this approach is not just for red states like West Virginia. It’s also, like the poem has it about roses and violets, for blue cities. But no matter the color of the flowers, austerity’s bloom is now bearing the fruit of resistance.

Like citrus fruits trucked north when the weather is still cold, the first fruits of teacher resistance were bitter and somewhat battered about. It’s thanks to the teachers that we know about Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel’s shuttering of underfunded, underperforming schools in poor communities of color. In 2012, the teachers in Chicago struck for a week. Officially, legally, they walked out as they fought for better wage and benefits—because that’s what the law restricts them to. But just as present in their discussion were school closures, opposed by most parents and community members.

Former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover famously called Americans who opposed the 1936 overthrowing of the democratically elected government of Spain [8] It wasn’t until 1940, when the US entered the war against Germany, Italy, and Japan (which backed and enabled the Spanish fascist coup), that the antifascism was “on time.”

Similarly, it’s worth pointing out that the national media was much less sympathetic to the visuals of Chicagoans of all races, led by a Black chemistry teacher, opposing Emmanuel’s policy than they were to later visuals from so-called Trump Country. We might call the Chicagoans, pace Hoover, “premature anti-austerians,” winter citrus, sour flesh bound in bitter skin, back in the halcyon days before the 2016 election.

Another slow-acting Miracle-Gro for the teachers’ uprisings: The 2017 Women’s March. Much was made then of the number of first-time protestors in Washington and the sheer number of local demonstrations. Union women—not just teachers—went, sporting union buttons on their pink hats. And 77% of public school teachers are women. One thing was clear: when Trump won, millions—many, perhaps mostly, women—awoke to the feeling of being totally, wholly unrepresented. As the old lefty slogan has it, “There is no justice, there is just us.” But man, there are a lot of us.

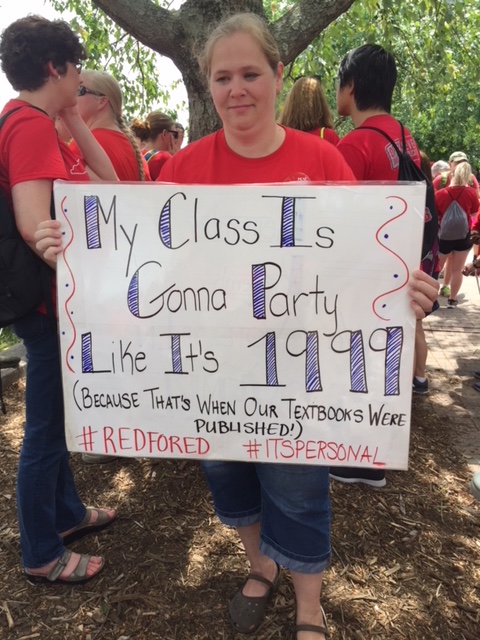

“Just us” is not new for women, or really for most people at or below the average teacher salary line of $58,950 (the national median salary for all households as of the 2016 census is $57,617).[9] That’s after years at it. Beginning teacher salaries don’t pay for school supplies, supplements to decades-old textbooks, and other classroom needs. A teacher friend told me she routinely spends upwards of $1,000 a year on her classroom. There is a generally understood social contract: because they make so little money, teachers get decent health and retirement benefits. West Virginia kicked off the rebellion by reneging on that deal.

In fact, coverage of the West Virginia teachers’ efforts began, mostly, with the news on how kids would be fed if schools closed.[10] (The shutdown in West Virginia wasn’t technically a strike because all fifty-five superintendents closed their districts’ schools, citing the safety concerns associated with the bus drivers’ promised participation in a strike. This, American Federation of Teachers leader Campbell said[11], was pivotal to their win. Public workers in West Virginia

For West Virginia teachers, bus drivers, and other school workers, a key priority was ensuring hungry kids would eat. A quarter of West Virginia kids live below the poverty line; more depend on free or reduced school lunches. Before the red T-shirts and the red bandanas, what viewers saw on the news was the iconic blue-and-orange boxes of instant macaroni and cheese. As we make our way through this, uneven, we move from citrus to blueberry to the later bright red cherries of #redfored.

That metallic blue is also the blue of the Facebook logo. Teachers in West Virginia, and then all over, began using social media to follow the events and plan their own resistance. Kentucky teachers coordinated a “sick out” (in which people take their sick day on the same day) to protest Governor Bevin’s budget cuts. Bevin then suggested kids had suffered child abuse as a result of the sick out. In turn, Oklahoma teachers went on an honest-to-goodness strike. Music teachers used Facebook to find one another, and the movement adopted an anthem—the 80s classic “We’re Not Gonna Take It” by Twisted Sister—when , thousands of red-shirted protests jumping and singing along.

When the uprising spread to Arizona, those music teachers picked up the tune.

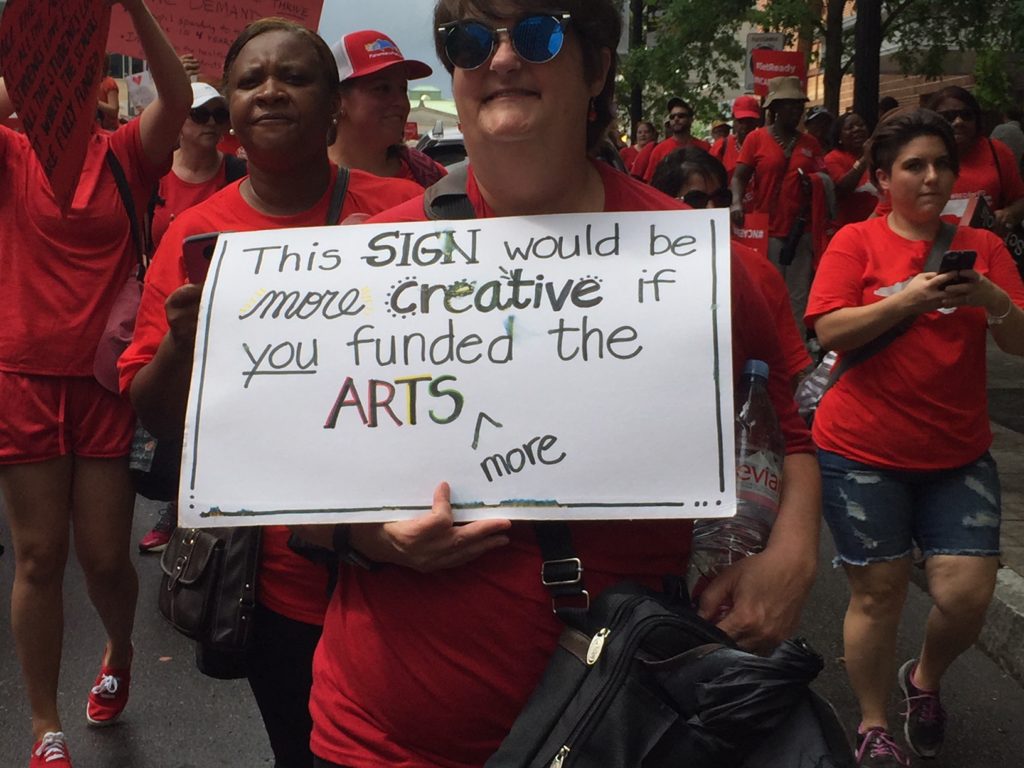

We’re here to represent because the first thing that gets cut is the music programs, it’s the arts,” said Lindsey, a teacher in the Paradise Valley Unified School District told a local journalist. “And that’s a big thing for us because we’re the first to go usually.[14]

It was in Arizona that the hashtag took off. It was catchy, and expansive. In Arizona, Navajo teachers created #rezfored.[15] In North Carolina, this season’s last flowering, many participants of all races wore Black Lives Matter buttons on their red shirts.

By May, when North Carolina teachers held a rally on the first day of the session of the legislature, the movement had gone from nascent spring to summer swelter. As in all the previous demonstrations, snarky signs (“Can you read this? You’re welcome.”), references to Hogwarts and “teacher voice,” adaptations of rap references (“straight outta pencils”; ), Dr. Seuss, plays on “thug” (a term commonly paired with “union”) and straightforward references to multiple jobs (“my second job paid for this sign”) along with more heartfelt, live-love-laugh style images (“my students are the reason”). North Carolina teachers added the #itspersonal hashtag to #redfored. (It too wasn’t technically a strike—everyone participating who needed time off from their school job took a personal day.)

Results, so far, have been mix—a bit of a salad, if you will—in this first growing season. West Virginia protesters won raises for all state employees; Oklahoma teachers won the first tax increases in that state since 1990[16]) and then beat back a ballot initiative to reverse it; Colorado teachers won X; North Carolina teachers, too, won partial victories. All say it’s a long haul. Austerity in the US has been around for forty years; it will take more tilling to uproot it.

Early fruits are promising, however. In states across the uprising—including places like Kentucky that didn’t get as much from their legislatures, or as much media attention—women who oppose austerity are signing up in droves to run for office because where they live there is no anti-austerity candidate. That’s not a slam on so-called flyover country—it’s a fight we’re seeing in New York and in California, too. As of July, [17] (including the 2016 National Teacher of the Year) and many more are running in local races. New candidates may (or may not) be members of Pantsuit Nation, their union, or the Democratic Socialists of America (which played an outsized role in several teacher efforts). New candidates are angry, and they have the advancers of austerity not red-faced (it seems impossible to embarrass them) but perhaps a bit scared.

There are other fruits, smaller, less flashy fruits, like this effort in McDowell County (West Virginia’s poorest county), where the teachers unions and others are working to offer a better, locally-based alternative to the environmentally and economically unsustainable dependence of fossil fuel extraction.

And there are less formed fruits, that bear more sunshine and scrutiny and need more encouragement. The teacher strikes are one of the few times we see working America doing the real, unglamorous work of social justice and community building via mass media. We are not refracted through the polished prisms of Women Who Work or Lean In or teetering on three inch heels like Michelle Pfieffer in Dangerous Minds. This is not Rosanne or Dirty Jobs. This is “What Work Is.”

We stand in the rain in a long line[18] and in May in North Carolina, the rain came and the rain went and the humidity hit the roof, but the long lines and large crowds did not diminish. Clustered into their districts, teachers confronted their representatives, asking for commitments to raise school funding. They cheered (and video-documented) those who agreed, and chanted “vote her out!” to those who wouldn’t commit.

Making a union, making a democracy, is slow and unglamorous work. Person by person. Conversation by conversation—sometimes awkward, sometimes intense. I watched strangers in matching shirts bond over working paycheck-to-paycheck, holding second jobs, loving the work and hating the pay, and their growing hope for better than this, the endless winter of American austerity. In the Facebook lives and Instagram feeds of #redfored, you can see people as we are, really, in this country and especially in the South and Southwest: T-shirted, tired, angry, shout-singing lyrics from Twisted Sister or Jay-Z or both. Unpolished and unashamed of it and unapologetically demanding better. In the sweat and sweatshirts, you can see tiny fruits begin to grow. We’ll see what ripens as we all, wearily, head back to school and into the 2018 midterms—“We’ll remember in November” the signs promised. But no matter the harvest this fall, some fruits of these fights will grow slowly, mostly out of the glare of our observation. May we yet discover many a wild and secret garden.

[1] For more on this, see Lane Windham’s Knocking on Labor’s Door, as well as Nancy Maclean’s Democracy in Chains and, if you still have time, Judith Stein’s Pivotal Decade and/or Kim Moody’s From Welfare State to Real Estate.

[2] Alvin Chang, “Arizona Teacher Walkout: How 3 Decades of Tax Cuts Suffocated Public Schools,” Vox.com, April 26, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2018/4/25/17276284/arizona-teacher-strike-tax-cut-funding-data

[3] Emma Brown, “With State Budget in Crisis, Many Oklahoma Schools Hold Classes Four Days a Week,” Washington Post, May 27, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/with-state-budget-in-crisis-many-oklahoma-schools-hold-classes-four-days-a-week/2017/05/27/24f73288-3cb8-11e7-8854-21f359183e8c_story.html?utm_term=.7ca4b04af322

[4] Emma Brown, “Katrina Swept Away New Orleans’ School System, Ushering in New Era,” Washington Post, September 3, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/education/wp/2015/09/03/katrina-swept-away-new-orleans-school-system-ushering-in-new-era/?utm_term=.f61f121738a8

[5] Lauren Lefty, “Disaster Capitalism and Vulture Charters,” Jacobin, March 3, 2018, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/03/teachers-strike-puerto-rico-hurricane-schools

[6] Edushyster, “The Long Game of Betsy DeVos,” Have You Heard (blog), November 29, 2016, http://haveyouheardblog.com/long-game-of-betsy-devos/

[7] Dale Russakoff, “Schooled,” The New Yorker, May 19, 2014, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/19/schooled

[8] John Nichols, “‘A Prematurely Antifascist’—And Proudly So,” The Nation (blog), October 26, 2009, https://www.thenation.com/article/premature-antifascist-and-proudly-so/

[9] United States Census Bureau, “Median Household Income in the United States,” September 14, 2017, https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/income-map.html

[10] Christopher Dawson, “Before They Went on Strike, West Virginia Teachers Packed Bags to Make Sure Kids Didn’t Go Hungry,” CNN.com, last updated February 27, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/26/us/iyw-striking-teachers-feed-students-trnd/index.html

[11] Jobs with Justice, “Labor Research & Action Network Members Help Build Power for Working People,” June 27, 2018, http://www.jwj.org/labor-research-action-network-members-help-build-power-for-working-people

[12] Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “The New Old Politics of the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike,” The New Yorker, March 2, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-new-old-politics-of-the-west-virginia-teachers-strike

[13] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “U.S. Federal Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs,” https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

[14] Alexis Egelend, “‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’: Arizona Teachers Band Together for #RedForEd,” April 29, 2018, azcentral.com, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-education/2018/04/29/arizona-teachers-form-redfored-spirit-band-perform-capitol-walkout/559101002/

[15] Laurel Morales, “Navajo Teachers Change Rally Cry to ‘Rez for Ed’,” Fronteras (blog), last updated May 4, 2018, https://fronterasdesk.org/content/638697/navajo-teachers-change-rally-cry-rez-ed

[16] “Tulsa World Editorial: Good News for Public Schools!”, Tulsa World, June 20, 2017

[17] Jennifer Fink, “From the Classroom to Congress: Meet Eight Teachers Running for Office in 2018,” We Are Teachers, https://www.weareteachers.com/teachers-running-for-office/

[18] Philip Levine, “What Work Is” in What Work Is: Poems (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52173/what-work-is

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.