“A vague gesturing towards that frame of reference”: David Wojnarowicz’s chaotic ekphrasis

Ekphrastic texts usually evoke an artwork in its absence, reproducing in text not just the details of the image but its affect. Wall texts, captions, catalogue texts—to what extent can these textual forms can be understood as genres of ekphrasis? Usually, they interact with the image within its presence; however, there are examples where text and image interact in more unpredictable and surprising ways, neither taking precedence.

A catalogue persists beyond the geographic and chronological scope of an exhibition, forming an archival document that outlasts its referent—artworks reproduced in miniature, in only two dimensions, and often in black-and-white, accompanied by texts that may or may not have featured within the exhibition itself.

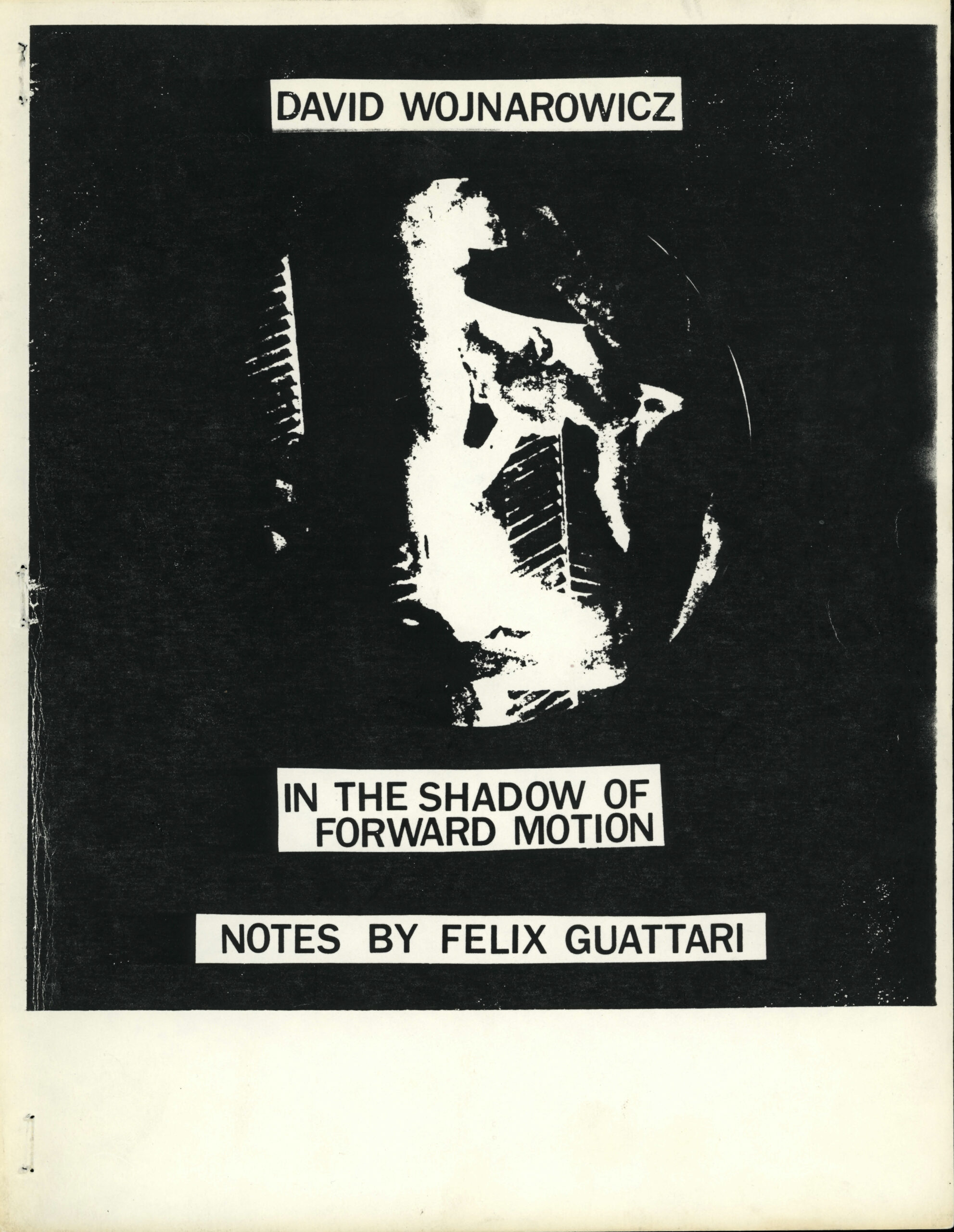

David Wojnarowicz

In The Shadow of Forward Motion (detail), 1989

xerox photocopy

8 1/2 x 11 ins. (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

I am taking as my case study an idiosyncratic example: a 1989 exhibition by the artist David Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of Forward Motion. For the show, he produced a catalogue in a run of about fifty hand-xeroxed copies. The booklet included a text—ranging from a single sentence to a whole typewritten page—for most of the thirty-one artworks he included (numbers 13, 17, 23, 25, and 30 only have titles). Each recto has a text and each verso, a collage of source material. None of the artworks are themselves reproduced in the booklet. A facsimile copy of the catalogue was issued by Brooklyn-based arts book publisher Primary Information in 2020 in a run of one thousand—twenty times as many as the original, and available internationally.[1]

things spoken in sleep

The catalogue contains “introductory notes” by psychoanalyst and philosopher Félix Guattari, organized, mediated, and translated by their mutual friend, the filmmaker Marion Scemama. (A significant proportion of Guattari’s text quotes Wojnarowicz’s own description of his practice, as relayed by Scemama.) By way of introduction, Wojnarowicz wrote the following, typed in all caps, with great emphasis—as if screamed not spoken, perhaps—but I have transcribed in standard formatting for ease of reading.

The notes contained in this book are not meant as literal explanations of the paintings photographs and sculptures in the show; they are rough notes, late night tape-recordings, things spoken in sleep and fragmented ideas which at times contradict each other—they are meant as notes towards a frame of reference; a vague gesturing towards that frame of reference.[2]

I want to pick up on this final phrase in particular: “notes towards a frame of reference; a vague gesturing towards that frame of reference.” Might an ekphrastic text frame its artwork—in that like a frame, it complements the work, yet the two can be separated. And the frame, removed from its artwork, demonstrates this lack while losing nothing of itself. These texts, Wojnarowicz notes, point or gesture towards the frame for its corresponding artwork. It should be noted that the frame of reference at this moment is deeply personal for Wojnarowicz—he was dealing with his own diagnosis with HIV and the recent death of his friend and mentor, Peter Hujar, of AIDS-related illnesses.

Wojnarowicz was a published writer as well as an artist and his memoir, Close to the Knives (1991), has become a defining part of his legacy.[3] How does an artist, rather than a curator or another third party, speak about his own work? Each artwork is complicated—rather than described or explained—by its text; each text is rooted in an artwork but persists and circulates independently. The two are not so much interdependent as intradependent. This dynamic establishes a symbiotic relationship between text and image, whereby both gain something from the other, a constant, ontological give-and-take. My appropriation of biological metaphor will become significant in this essay, as the line, the border between nature and culture is explored and problematized throughout this body of work.

Ekphrasis: from the Greek ἐκ (ek) and φράσις (phrásis), “out” and “speak” respectively, and the verb ἐκφράζειν (ekphrázein), “to proclaim or call an inanimate object by name.” These texts proclaim a frame for each artwork that surrounds and contextualizes the work. The metaphor of the frame resonates, in many cases, with the literal act of framing in many of the photographs and photographic works: Untitled (Buffalo) is presented with a plain white mount; Weight of the Earth, Part I and Part II both combine multiple photographs in regular, geometric grids.

Wojnarowicz aspired, initially, to become a poet and performer, but published only minor texts at first. He performed poems as lyrics during his time with the band 3 Teens Kill 4. The exhibition catalogue features a lyric fragment and, printed on the final page, a long poem that he later reworked into a passage within Close to the Knives. In artworks produced after this body of work, he would incorporate text directly into the art, blurring the boundary between text and image in his practice.

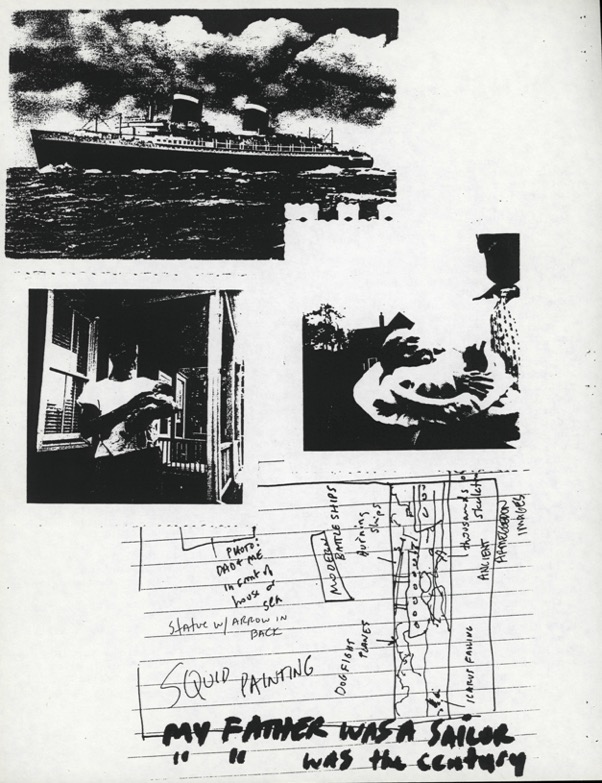

David Wojnarowicz

In The Shadow of Forward Motion (detail), 1989

xerox photocopy

8 1/2 x 11 ins. (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

At In the Shadow of Forward Motion, the various artworks and their corresponding texts share congruent frames of reference. To better understand this dynamic, I want to focus on a select number of artworks. It will also become necessary, though, to detour via Wojnarowicz’s writings, including his neologisms and personal turns of phrase, like the “preinvented world” (sometimes “pre-invented world”).

Nonetheless, the processes at play here are more general than Wojnarowicz’s practice alone and offer an insight into the potential for ekphrasis writ large. Of course, there is no single dynamic for ekphrasis: some of the most famous examples in literature detail lost or unknown works of art, so such dialogue can no longer exist. I am interested in theorizing possibilities for ekphrasis—thinking about how text and image might combine in such a way that exceeds either in isolation.

a sense of impending collision

Wojnarowicz repeatedly described In the Shadow of Forward Motion in terms of acceleration, speed, and machinic motion. He explained the title of the show explicitly in a tape journal: “The meaning of that title is: Consider that you’re in a car and you’re speeding along an expressway, and everything you see out of the corner of your eye that doesn’t register in pursuit of that speed, in terms of motion, is what’s in the shadow.”[4] This explanation verges on meaninglessness, complicating its terms through association but hinting at an interest in what goes unnoticed, or is noticed only unconsciously. It is highly suggestive but ultimately more obfuscating than elucidatory.

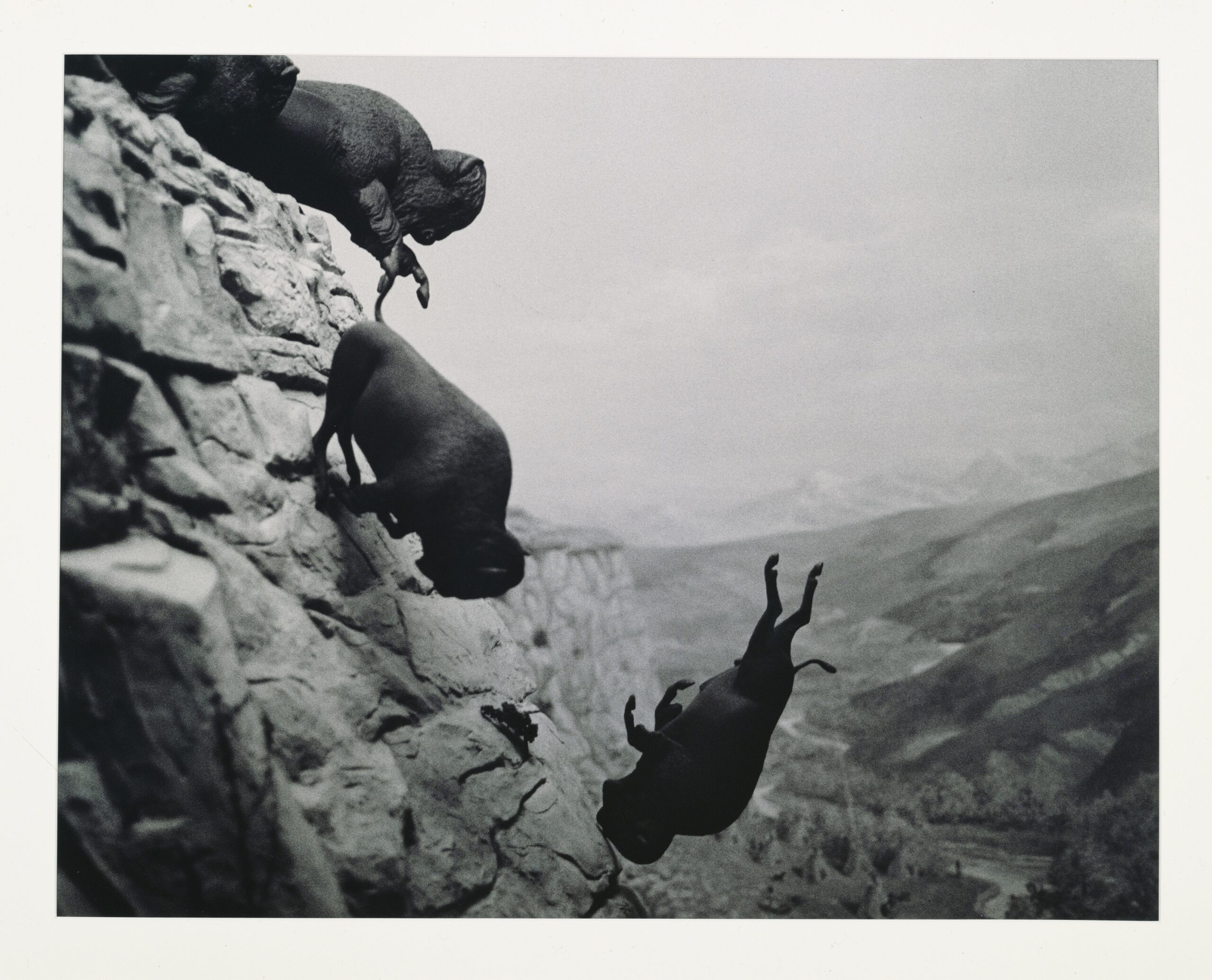

Untitled (Buffalo) (1989) has to be one of the most famous artworks by Wojnarowicz. A cropped version of the work would appear on the first American edition of Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives, but the piece was first exhibited as a gelatin silver print (in an edition of five) at In the Shadow of Forward Motion. “A metaphorical image for the title of the show,” Wojnarowicz wrote of this work; “a sense of impending collision contained in this acceleration of speed within the structures of civilization; speed of consumption; speed of transportation; speed of transport and mixing of cultures.”[5]

David Wojnarowicz

Untitled (Buffalos), 1988-89

gelatin silver print

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

The buffalo, falling—ambiguous in those two words as to whether it is one or many—caught, seemingly, between life and death. They are falling—an inevitable death upon landing. Suspended in the present tense—falling, not yet fallen; the future perfect looms—they will have fallen, they will have died. “When they invented the car they invented the collision,” Wojnarowicz writes in Close to the Knives: a sense of tragic inevitability predicated on human intervention.[6] A student pointed out to me that a blurry, out-of-focus reflection of Wojnarowicz’s own face can be seen in the photograph—the artist present in the work, implicated in its construction and, of course, reflecting his own mortality.

“It’s that moment of recognition of an entire society being asleep for a very long time and the dreams becoming so tiresome,” he writes in the first of the catalogue’s texts; it is not only the artist himself who dreams but the whole of society. “It’s the moment of recognition of an entire civilization driving forward at a faster and faster rate of speed and the moment of realization that we are sleep at the wheel and the sound of the impact is not so far ahead.” This quote summarizes not only the subject of Wojnarowicz’s work but also his process: anticipating this impact and emphatically opting not to stop it.

This image might read as a natural history photograph, something Wojnarowicz was keen to encourage for some time: “After a while when people would ask about the image I would just automatically say ‘Yeah, I was there…’ and then if they’d say ‘Well, how did it happen? I’d say I had some firecrackers with me I set them off behind the herd, rushed to a cliffside, and documented it.”[7] He describes the work here as authentic testimony when it is anything but: a carefully cropped and desaturated photograph of a diorama.

Wojnarowicz notes at the outset of the catalogue, immediately after the sentence describing the “vague featuring towards that frame of reference”:

One late summer night down on the shore of Charleston, South Carolina, some friends of mine and I opened a box of fireworks that contained a series of small gunpowder filled space rockets. We snapped the wings and air-blades that determined flight direction off the sides of each rocket before lighting the fuse; what resulted at the moment of launch sometimes had us throwing ourselves to the ground covering our heads or running down towards the midnight waves with a flaming projectile close at our heels.[8]

How does this anecdote further explain the texts contained within the catalogue? Its placement would indicate that some related connection is at play. What does tampering with fireworks on a beach have to do with this body of work? It rhymes with the false anecdote of the buffalo: something unpredictable, destructive. Again, it feels like an identification with the buffalo: their being spooked over a cliff; his running through the night.

The falling buffalo are revealed to be a lie: “Actually, the buffalo thing is a small part of a large diorama in the Natural History Museum in Washington.”[9] We might think of this work as akin to a Duchampian readymade: it is the act of selection and the process of displacement that forms the work. “Whereas dioramas invite reverie and diffuse critique,” notes Mysoon Rizk, “Wojnarowicz’s exclusions and collages startle viewers into a conception of alternate realities. His work instigates critical inquiry, provoking curiosity about withheld information and motivating new questions and recognitions.”[10] As much as providing information and experience in his work, Wojnarowicz provokes his viewer, encouraging a self-reflexive process of critical analysis, a dialogue between viewer and artwork.

It was believed—more: taught—that buffalo would regularly and routinely be killed in such ways: a cruel, indiscriminate slaughter. Rizk writes that “natural history museums have fixatedly reminded viewers that human pedestrians really did force ancestral bison to stampede over cliffs” while simultaneously failing “to address Euro-American culpability with regard to the conduct of shocking eradication campaigns of both bison and Native American life.”[11] It is the framing the photographic composition here—what gets included and what gets excluded from the piece—that sits at the core of this work, adjusting both context and content. The full diorama includes figurines of Native Americans, painted in bright colors, herding the buffalo toward the cliff edge; Wojnarowicz crops out these inaccurate figures, drains the scene of its lurid saturation.

Institutional knowledge production in America blamed Native American tribes for the widespread depletion of buffalo as a resource, which in turn threatened their food supply and, thus, their own existence. It’s not difficult to see parallels with similar institutional approaches to AIDS and gay men in America: stubbornly persevering with their barbaric traditions (promiscuous gay sex) is the cause of their downfall and death—a moralistic, prejudiced condemnation. In truth, it was the United States government that not only sanctioned but encouraged the slaughter of buffalo: “Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone!” ran one such slogan.[12] Such disinformation characterized—still characterizes—a particular, right-wing approach to American history: leaving out vital context and, when this fails, spreading misinformation in its place. Wojnarowicz doesn’t rebuff such lies but instead attempts to expose the processes of manufacturing such propaganda.

In the buffalo photograph, the act of framing—the scene of framing—is the essence of the artistic gesture. To establish a frame of reference for Untitled (Buffalo Falling), a work haunted by impending death, Wojnarowicz evokes a sudden sense of revelation: “like the sensation I’ve had after coming out of hospital after a long illness and seeing everything as if for the first time; with more clarity that one can be expected to endure; something like an x-ray of civilization; the structure of everything revealed in the simple immobility of the legs before the red of a traffic light and the whole street rushing with humans.”[13] It is sudden shift in the frame of reference, new perspectives streaming in and others instantly foreclosed; such reframing takes place, directly and assuredly, in the buffalo photograph. Wojnarowicz wants us to stop—not because we are told to, though, as by a red light—and take a step back to consider the structure of things, how systems of signs are structured, how bodies under biopower are sutured.

He describes these structures as our “preinvented” existence, a neologism that becomes vital in understanding this body of work. The “preinvented” denotes the structures and institutions that we are born into, the predate our subjectivity, from systems of government to language itself (not entirely dissimilar to the symbolic, within a Lacanian model of psychoanalysis). Wojnarowicz explicitly characterizes this existence as a machine: “But the originators of this existence are long dead. It’s like a machine that runs itself that can’t stop. The way things are set in motion, the machine of the society continues running long after groups of people have tried to pull out the plug.”[14] He also writes that “we’re supposed to quietly and politely make house in this killing machine called America and pay taxes to support our own slow murder”—and evidently these two machines are interlinked: society moves unstoppably onwards, destroying anything in its path, anyone who dares to defy or escape its machinations.[15]

the invention of the word nature

Included at the exhibition was a painting with the same name: In the Shadow of Forward Motion (1988–89). This isn’t, per Wojnarowicz, the “metaphorical image for the title of the show”—what links does its title suggest? How does this particular work both work with and against the ideas that underpin the exhibition? It is a large mixed-media work, predominantly paint on a collaged background of sheet music; two painted frogs dominate the composition, with a peculiar building—part pastoral, part industrial—looming in the background. Tadpoles—or are they sperm?—form a border: in his diaries he notes our common “tadpole ancestors.”[16]

“I returned recently to one of the last rural new jersey towns I’d lived in as a child before coming to new york at age 8,” Wojnarowicz wrote of this piece.[17] There is a sense of revisiting childhood memories and, therefore, regression. Wojnarowicz seemingly couldn’t escape the trauma of his childhood, try as he might, and instead endlessly returned to it—both thematically in his work and physically. He added: “I also have a powerful memory of one summer a group of teenagers coming around the pond and catching frogs. Most of the frogs had five or six legs.”[18] The tale illustrates the strangeness of nature, its inherent absurdity, and the encroachment of humanity’s polluting influence on the natural world. A New York Times article from 1964, “Frogs With 5 Legs And More Found In Pond in Jersey,” would seem to corroborate Wojnarowicz’s improbable story.[19] “I went back to this town to see this pond again and found that it had been paved over and a police station was built on top,” he adds; “I found this oddly fitting. The sources of contamination attracting the human counterparts.”[20] It’s a snide criticism of the police, one in keeping with Wojnarowicz’s consistently anti-establishment and avidly anti-police sentiments.

David Wojnarowicz

In The Shadow of Forward Motion, 1988-89

acrylic and collage on canvas

36 x 36 ins. (91.44 x 91.44 cm)

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

In In the Shadow of Forward Motion, there are two frogs, both seeming to have the normal number of limbs. One is grasped by an anonymous hand; the other floats atop the composition, its skin peeling away to reveal cogs. If we are to read this tale as one of contamination, of humanity colonizing and corrupting nature, this frog is thus afflicted. The tadpoles—or sperm—swim out from one of the frogs, threatening to spill outwards: unbounded, infectious and infecting. Each sperm-tadpole has at its center a small circle cut from a map. Both tadpoles and sperm are the beginnings of something—a frog, another animal—they change and grow, inevitably.

Similar seeds are found on Seeds of Industry (1989). Here, they are cut out of currency: maps and money, motifs Wojnarowicz used to connote our preinvented existence, the ways in which we symbolically break down, represent, and remake the world. Of this piece, Wojnarowicz writes a sequence of provocative associations that seem to speak directly to In the Shadow of Forward Motion, both the painting and the wider exhibition:

Again; the invention of the word nature; the dismantling and reforming of it to fit the needs of industry; the marriage of the machine and biologic structures; evolution; seeds: veins being an anagram of vines; the growth of it; the flowering of it all; the petals of gaseous black smoke.[21]

This long, meandering sentence moves from organic metaphors into the technological, as well as combining the two: seeds of industry that flower into petals of black smoke.

It is the organic and the technological that are combined, contrasted, and blurred together in In the Shadow of Forward Motion: everything is part of this machine, this preinvented existence. Reproduction—suggested by the tadpoles and frogs—perpetuates the contamination. Breaking the division between nature and culture might put a stop to this. Contemporary society has become an unstoppable, self-perpetuating machine, one briefly glimpsed in this work. Wojnarowicz might aspire to ultimately shut down this machine; he compromises, somewhat, in merely exposing the machinery itself. As he declares in a contemporaneous essay, “bottom line, with enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.”[22] Both nature and culture circle around, predicated on generational cycles of repetition and inheritance. How to halt this cycle, this machine and its (death) drive? There’s no straightforward answer here.

Monkeys are a recurring feature in Wojnarowicz’s art and speak directly to this division between nature and culture. Monkeys and apes take on human attributes, or have them imposed: a monkey dressed in a shirt and trousers walks across Evolution (1987), with the source photograph appearing on Weight of the Earth Part II; an ape holds a log as a club on Fire (1987); a photograph of a monkey in overalls is the focal image in Fear of Evolution (1989). A specific example of a monkey recurs throughout Wojnarowicz’s notes and journals, including this exhibition catalogue: “I don’t have many heroes but one that I carry close to my heart is the cosmonaut monkey the russian government put into space a few years back. They had to cancel the flight mission and recall the capsule back to earth because the monkey became excited in space and broke free of its restraints and began smashing buttons and dials on the control panel.”[23] Here, an anonymous monkey works not only to resist but to undo and destroy technological progress.

On Seeds of Industry, Wojnarowicz paints a monkey with a hat and jacket, “collecting coins in a bowl for some street vendor or street musician.”[24] He elaborated: “You can look at this monkey sitting with its bowl of coins and think it’s an unbelievably pathetic image—that the nature of this animal is reduced to collecting coins.” The monkey is chained, its bowl empty. Wojnarowicz uses this image to gain a sense of perspective upon the human condition, exposing our hypocrisy in believing ourselves superior: “we won’t look at ourselves collecting coins and think that that’s a sad image, that somehow it’s an unnatural activity. Animals allow us to view certain things that we wouldn’t allow ourselves to see in regard to human activity.”[25] He also uses ants, with their complex colony structures, to similar ends, demonstrating the absurdity and chaos of human society. This shift in perspective exposes the natural as unnatural and the unnatural as natural; more: it challenges any neat delineation between nature and culture: they both outline, define, and surround each another.

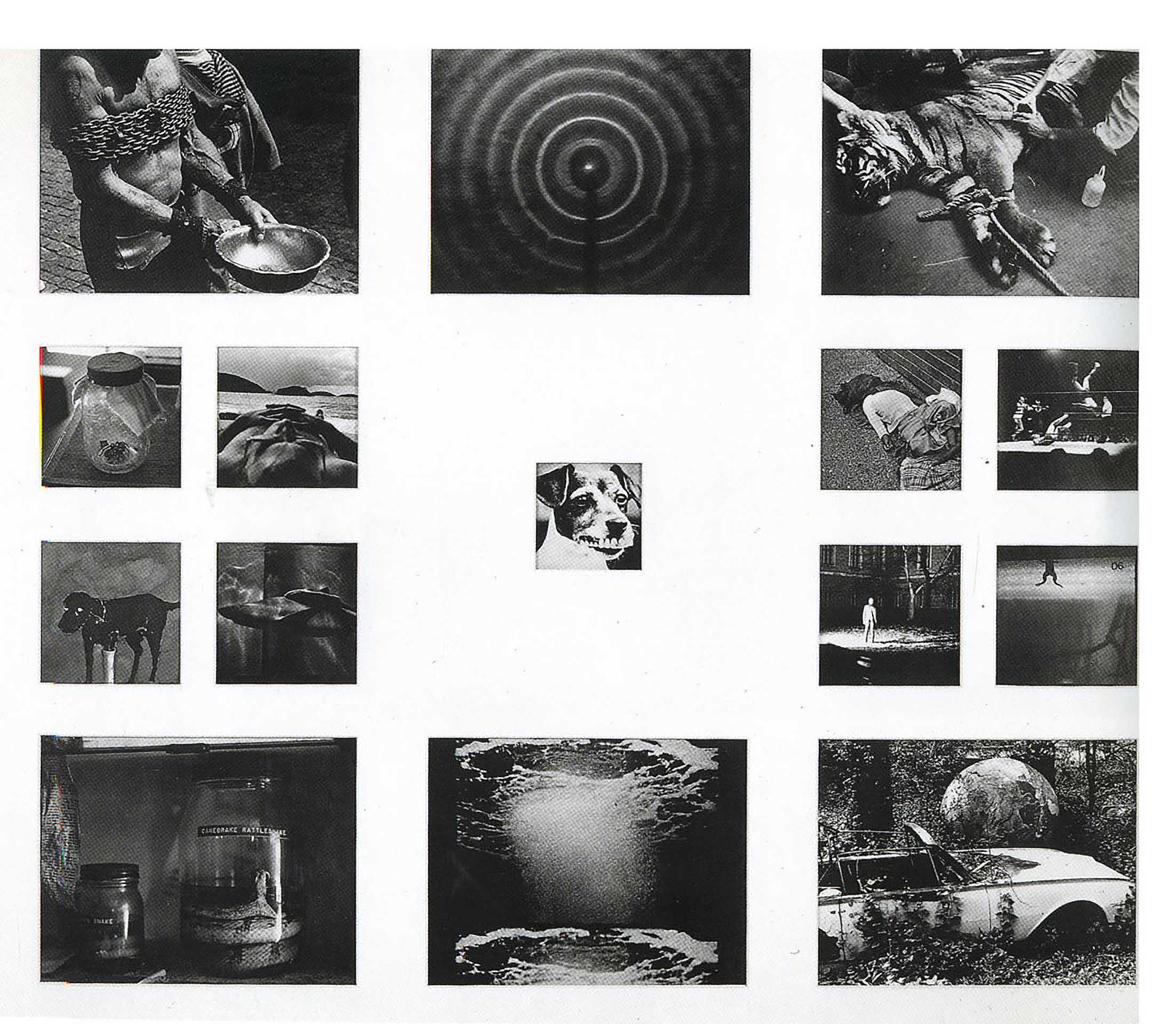

an opera in the form of images

The preinvented world is inescapable. We do not choose the circumstances of our birth; we are thrust into a world that existed long before our individual existence and will continue to exist long after our death. This preinvented world is formed of structures and systems that we can understand but struggle to resist, from language itself to social norms and systems of exchange. Such structures seem profoundly sensible and incontrovertible; natural, even. Yet to live outside, beyond, or without these structures would render existence chaotic, unassimilable, hermetically asocial. At times, though, this preexisting existence carries an immense weight, becomes a burden: “it’s the heaviness of the pre-invented existence we are thrust into,” Wojnarowicz writes.[26] He describes this existence as “the instruments of control and policy that are formed before we are born and which we adapt to or get consumed by.”[27] In the catalogue, he notes: “it’s an opera in the form of images where each frame is a clip from films of living sounding a particular note like each word that makes up a sentence…”[28] “The two photo pieces,” he explains, “‘The Weight of the Earth,’ part 1 and 2, are in my mind an opera that could actually have hundreds of parts instead of just two.”[29] The Weight of the Earth, Part I and The Weight of the Earth, Part II now exist independently of each other, in separate collections.

David Wojnarowicz

The Weight of the Earth, part I, 1988

14 silver prints and 1 watercolor

39 x 41 1/2 ins. (99.1 x 105.4 cm)

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

The Weight of the Earth, Part I and Part II are both formed of a matrix of fourteen photographs, of differing yet ordered sizes, with a single watercolor sketch disguised amongst the photographic simulacra. Without the materials listed alongside the work, as is customary in galleries, one might—perhaps is meant to—miss this intrusion of the painted into the photographic, the imaginary into the indexical. Many of the photographs seem objective, documentary in their framing and subject, while others seem edited or as if they are captured from another screen, a record of a record(ing).

David Wojnarowicz

The Weight of the Earth, part II, 1988

14 silver prints and 1 watercolor

39 x 41 1/2 ins. (99.1 x 105.4 cm)

Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York

It’s difficult to characterize these works: they cannot merely be described as photographs, but neither are they conventional collages or photomontages, as each discrete element retains its independence while nonetheless being in concert with the others. “Each photo shows almost more than words can describe,” Cynthia Carr wrote in ARTFORUM. “These images resonate with and against each other. They’re subtle. On a worksheet, David scribbled, ‘Weight of the Earth is about captivity in all that surrounds us.’” In isolating these parts of the world, he captures them. Inclusion into an identity is predicated on exclusion from that same group.

Most of the photographs in these photo matrices has a single subject—a flag, a dog, the moon—with exceptions in the Ant Series, where isolated motifs are pictured swarming with ants. In his notes and plans for these works, and others, he generally describes each image with a single noun. This form finds an unconventional parallel in the catalogue, where Wojnarowicz writes: “THE EYE THE SPHERE THE GLOBE THE WINDOW OF CONSCIOUSNESS / THE PORTAL TO SLEEP AND WAKING THE ENTRANCE TO THE CINEMA OF BIOLOGIC THRUST.”[30] Devoid of punctuation and syntax, it is an asyndetic list of objects awaiting description (adjectives), direction (prepositions), and instruction (verbs).

Wojnarowicz explains, briefly, the significance of the ant on the eye in the center of Weight of the Earth Part I: “it’s the human irritation at the sight of uncontrolled ‘nature.’”[31] Nature stands apart from the preinvented existence, before its Symbolic hierarchies. The very designation of nature, this act of othering, separates the natural from the cultural while, at the same time, coopting it. In an interview, he says, “I was thinking of human society’s rejection of nature. That came from thinking about the word ‘nature,’ which we immediately distanced ourselves from the moment we invented the word for it, even though we’re part of it.”[32] His art works to bridge this divide, or even to heal this gaping wound; “I’m really interested in breaking down the distance between humans and nature. I look in the animal world and find the counterparts to the technological/human world.”[33] Nature might speak to culture as much as culture speak to nature; from the natural, we might unmake the cultural, unleashing the repressed instinct—the lion in the zoo, perhaps—both literally and metaphorically.

In physics, weight is defined as the force resulting from gravitational pull on the mass of a body. On Earth, weight is therefore the effect of Earth’s gravity on individual bodies. The sum total of the Earth’s gravitational pull on itself is zero. Weight—unlike mass—is about relationships, between the small and individual, and the large and inescapable. “The weight of gravity,” Wojnarowicz writes; “the pulling in to the earths surface of everythings that walks crawls or rolls across its surface.”[34] Everything, everyone is pulled downward, to the surface where we might walk, crawl (as a baby), or roll (in a vehicle). Similarly, we are all inevitably born into a preinvented existence, offered neither alternative nor escape; it exerts its power on us much like gravity. Brian Massumi describes this dynamic, explaining personal freedoms in terms of gravity: “Freedom is not about breaking or escaping constraints. It’s about flipping them over into degrees of freedom… No body can escape gravity. Laws are part of what we are, they’re intrinsic to our identities.”[35] Massumi is a philosopher and social theorist, here exploring the limits of freedom. Certain laws are inescapable. Wojnarowicz represents the refusal of such laws, the desire to somehow defy gravity. Law always has its limits: gravity wasn’t invented by Newton, just observed, described and explained. Some systems are inescapable. It is not about escaping but navigating them—and understanding them.

Indeed, this same dynamic is observed by Freud and articulated in Civilization and its Discontents: mankind, he notes, “first appeared [on earth] as a feeble animal organism and on which each individual of his species must once more make its entry (‘oh inch of nature!’) as a helpless suckling,” no matter how much technology and science and civilization is developed to divorce mankind and nature.[36] This parenthetical phrase—“oh inch of nature!”—in English in the original, is the key observation here. As Joan Copjec explains, parsing this quote by Freud: “For the very segmentation and measurement of nature denatures it; an inch of nature is itself unnatural, found not in nature but in the rods and rules by which culture calculates.”[37] Trying to understand nature necessarily denatures it, imposing cultural norms onto natural forms. Nature only remains truly natural as long as it remains free. Wojnarowicz represents, with characteristic cynicism and suspicion, the human desire to colonize nature.

In detailing Weight of the Earth, Wojnarowicz adds: “it’s the film projectors gone convulsive; the scattering of associations, sensory and physical.”[38] Convulsiveness, with its connotations both of violence and uncontrollability, suggests a degree of chaotic interaction, one that inherently resists conventional order. A personal chaos escalates through these works towards a chaotic order. This pair of works interrogates the inherent structuring of meaning and order, confronting each other and their viewer. It is an illusion of order that reveals all order to be illusion.

all this will be picturesque ruins

Ekphrasis—literally, out speak. Wojnarowicz certainly was outspoken. His writings speak for themselves, so to speak.

There is one artwork in the show—number nineteen, Untitled Sculpture—that I have been unable to identify within Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre, even after discussing the work with his gallery and other researchers. There exists only a blurry installation photograph where the sculpture in question is barely legible, and a preparatory sketch, I think, within the catalogue. A crudely drawn wooden doll resembles, I would say, Donald Trump: an eerie premonition. He is strapped to a firecracker—once again, we return to pyrotechnics.

The text remains, it has survived. Here, he describes aspects of the work, including a wooden doll that he found washed up on a beach: “I love the stain of rust where a nail might have once penetrated, in the area of the abdomen where an umbilical cord was once attached giving life.”[39] He moves beyond mere description, adding: “the marriage of machine and biologics. The soldier and the killing head. The battery/ the source of power/ government/ fuel.”[40] We have a personal collection of references and ideas that speak beyond the artwork itself and have a poetic intensity in their own right.

“Someday all this will be picturesque ruins,” he writes; “Even this gallery; the cool white walls and the perfect electric lighting.”[41] The text is acutely aware of its context—as a catalogue text, for a gallery exhibition, intrinsically tied to a specific artwork—while also looking towards its uncertain future. For Wojnarowicz, this frame might be part of the “preinvented” world—his complex interplay of text and image draws attention to this otherwise invisible, somehow inevitable structure.

The text points to—constructs—a frame for the artwork: each artwork shares a frame of references with its text. Or, perhaps, each text frames its artwork, which in turn frames its text, metaphorically speaking. In some four-dimensional space, they frame one another; neither takes precedence and they remain inextricably bound.

A frame isolates—drawing attention to its object, isolating it from that which extends beyond. These texts continue to serve as both a reminder and a remainder of that which lies beyond the edge of the artwork, the preinvented structures that produce each artwork—and, moreover, that each artwork was produced despite these preinvented structures.

This, I wager, is applicable to ekphrastic texts more broadly: while Wojnarowicz offers a case study rooted in an idiosyncratic context—personally and politically—the structures at play are widely applicable. Text and image structure one another. This relationship becomes a constant reminder of the world beyond the frame—beyond the canvas, plinth, or page—that constructs both text and image alike. Neither explains the other; neither exceeds its other. It is a symbiotic relationship—one that reaches beyond immediate geography and chronology. Even as the text and image are separated—even as one becomes missing or absent from the archive—this relationship persists, forming a forgotten part of the other’s frame.

[1] David Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of Forward Motion (hereafter: ISFM), 1989, n.p..

[2] Wojnarowicz, ISFM, n.p..

[3] David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1991), 94.

[4] David Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth (Semiotexte, 2018), 132.

[5] “6. UNTITLED: (Falling Buffalo),” ISFM, n.p..

[6] Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 55.

[7] Barry Blinderman, “The Compression of Time: An Interview with David Wojnarowicz,” in David Wojnarowicz: Tongues of Flame, ed. Laurie Dahlberg (Normal, IL: University Galleries, 1990), 51.

[8] SFM, n.p..

[9] Blinderman, “The Compression of Time,” 51.

[10] Mysoon Rizk, “Looking at ‘Animals in Pants’: The Case of David Wojnarowicz,” TOPIA 21 (2009), 137-160, 142.

[11] Rizk, “Looking at ‘Animals in Pants’,” 140.

[12] J. Weston Phippen, “‘Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone’,” The Atlantic, May 13, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/

[13] “6. UNTITLED: (Falling Buffalo),” ISFM, n.p..

[14] Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth, 122.

[15] Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 93.

[16] David Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream: The Diaries of David Wojnarowicz, 2000, 60.

[17] Wojnarowicz, “20. IN THE SHADOW OF FORWARD MOTION,” ISFM, n.p..

[18] “Wojnarowicz, “20. IN THE SHADOW OF FORWARD MOTION,” ISFM, n.p..

[19] The New York Times, “Frogs With 5 Legs And More Found In Pond in Jersey,” September 5, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/09/05/archives/frogs-with-5-legs-and-more-found-in-pond-in-jersey.html

[20] Wojnarowicz, “20. IN THE SHADOW OF FORWARD MOTION,” ISFM, n.p..

[21] Wojnarowicz, “18. SEEDS OF INDUSTRY,” ISFM, n.p..

[22] Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, 100.

[23] Wojnarowicz, “1. FEAR OF EVOLUTION,” ISFM, n.p..

[24] Blinderman, “The Compression of Time,” 58.

[25] Blinderman, “The Compression of Time,” 58.

[26] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[27] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[28] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[29] Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth, 128.

[30] Wojnarowicz, “2. UNTITLED (Ant & Eye),” ISFM, n.p..

[31] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[32] Blinderman, “The Compression of Time,” 58.

[33] Blinderman, “The Compression of Time,” 58.

[34] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[35] Brian Massumi, Politics of Affect (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 17.

[36] Sigmund Freud, “Civilisation and its Discontents (1930)” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis, 1981), 21:91.

[37] Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists (Verso, 2015), 42.

[38] Wojnarowicz, “21. THE WEIGHT OF THE EARTH PART I and II,” ISFM, n.p..

[39] Wojnarowicz, “19. UNTITLED SCULPTURE,” ISFM, n.p..

[40] Wojnarowicz, “19. UNTITLED SCULPTURE,” ISFM, n.p..

[41] Wojnarowicz, “19. UNTITLED SCULPTURE,” ISFM, n.p..

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.